One notable milestone on the path to industrialised, ‘total’ war was the increased importance of out-producing as well as out-fighting an opponent. Despite the Entente – and Britain in particular – enjoying a superiority in industrial and manufacturing capacity at the beginning of the First World War, direction and organisation was somewhat lacking before the establishment of the Ministry of Munitions. Although this was partly the result of vastly increased demand on a private sector that was not adequately prepared for the trials of war, it nonetheless led to shortages in essential supplies. Given the scope, complexity and nature of the Ministry’s work from the summer of 1915 onward, it would be difficult to enter a detailed analysis of its performance in this blog – after all, the official history ran to 12 volumes. Instead, this post will explore the theme of shell production and the early impact of the changes the Ministry oversaw.

Reeling from the failure of the British army’s first planned offensives of the war in 1915, the country and its leadership – both political and military – largely welcomed the idea of centralising war production. From the summer of 1915 the new Ministry of Munitions took control of the development and manufacture of an increasingly broad range of equipment and war materials. As part of this process it oversaw a dramatic rationalisation of the systems of production and the coordination of state and private industries.

By the end of the war, the Ministry’s responsibilities covered a vast area of administrative direction. Not only did it supply and manage the production of small arms (rifles and machine guns), artillery, ammunition and explosives for the War Office, it also administered the design process for novel inventions to tackle the distinct challenges of the war. Despite all of this process and structure, however, there remained some controversy over just how successful the Ministry was at delivering ammunition, particularly during the first year of its existence.

In a memorandum written in 1919 by Walter Layton – the Ministry’s Director of Munitions Requirements and Statistics – it was stated that shell orders placed and fulfilled solely by the Ministry ‘did not yield results until the beginning of 1916, and in the case of the National Projectile Factories [establishments built by the Ministry exclusively to produce shells] until the summer of 1916’. As a result, the shells fired at the Battle of Loos in the autumn of 1915 and through the defensive period that followed into the spring of 1916 were the products of War Office orders (MUN 5/181/1300/95).

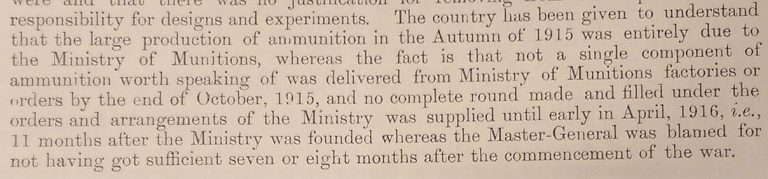

Writing in the same year, Major-General Sir Stanley von Donop – previous Master General of the Ordnance and thus the man once responsible for munitions production – agreed, stating that ‘the supply [of shells] gradually increased until in October 1915 it reached 1,200,000 and in that month there was not a single round produced under any orders from the Ministry of Munitions. The supply then fell off for three months and it was not until April 1916 that the first round with all components produced from orders of the Ministry of Munitions and filled at their factories was produced’ (WO 79/84).

Part of Major-General von Donop’s summary from ‘The Supply of Munitions to the Army’. Catalogue reference: WO 79/84.

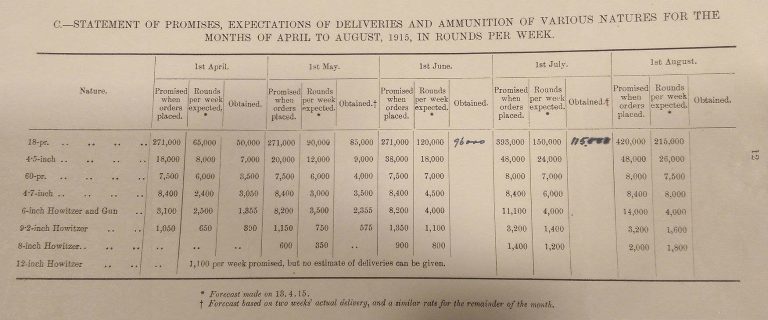

Striking though both statements are, in truth they hide the considerable work untaken by the Ministry of Munitions at the end of 1915 to ensure the War Office’s shell orders were actually delivered. As demonstrated by the table below, what was ordered and subsequently promised did not necessarily materialise.

Statement of ammunition ordered, expected and obtained, April-August 1915. Catalogue reference: WO 79/84.

Unlike von Donop, however, Layton looked beyond these raw statistics. Elsewhere in his memorandum he heralded the work of Sir Glyn West, Deputy Director General of Munitions Supply, for his work in bringing together shell components from different firms. The problem with the pre-war system was not just that it produced too few components to build shells, but that the components themselves – shell cases, propellants, detonators and the like – were not equally distributed among contracted manufacturers. This often meant delays to production runs as these manufacturers waited for particular parts. Instead of trying to meet the individual needs of the factories, West’s department concentrated on redistributing what they already had, ensuring those contractors nearest to delivering their orders had access to the components they needed to finish them (MUN 5/181/1300/95).

Elsewhere within the fledgling organisation, information concerning the country’s manufacturing capacity was also being gathered, allowing heavy machinery to be freed up from private work to concentrate on state munitions contracts. Other departments – such as the recently created Trench Warfare Supplies – were able to make much more obvious and immediate contributions. Following a call from General Sir Ian Hamilton about the urgent need for more hand grenades in Gallipoli in July 1915, the Department was able to make and dispatch a sizeable quantity within seven days; by November, they were overseeing the production of 800,000 a week (MUN 5/195/1600/15, MUN 5/195/1600/16, MUN 5/195/1600/10).

Having been relieved of such a significant responsibility by the Ministry of Munitions, von Donop and his War Office colleagues were understandably keen to defend their reputation and share the praise for the improvements in shell delivery seen through the end of 1915. Nonetheless, it was through the Ministry of Munitions’ efforts to rationalise the system it inherited by redistributing heavy equipment and shell components, and by establishing a specialist arm to provide trench supplies, that it was able to improve the delivery of war materials soon after its establishment. By late 1916 this system was producing 18 pounder shells at such a rate that it could match the annual output of 1914 in just three weeks.

Though seemingly adequate in peacetime, this episode demonstrated that the War Office’s direction of munitions production in a conflict of this scale was ineffective and inefficient. Without the ability to control private and public manufacturing, the labour force, raw materials and a host of other variables, it was hamstrung from the beginning. In comparison, the purpose-built Ministry of Munitions started with just four departments in 1915 and ballooned to more than 50 as its roles and responsibilities were extended. By hiring business-savvy, capable civilians (Sir Glyn West, for example, was also connected to the armaments giant Armstrong-Whitworth), it adopted a very different approach to managing production, which, combined with vastly increased powers and reach, allowed it to smooth the bumps that had tripped up the War Office. Though it continued to court controversy for the rest of the war, it was because of efforts like this that the Ministry of Munitions played such a significant part in the victory that came three years later.

Production is, of course, just one of many significant themes that can be drawn out from the history of the Ministry of Munitions. Others, including technology, the female workforce and the control of labour will be explored via this blog throughout 2015.