A new Law of Antiquities was approved in Iraq in 1924, as the country was under a British Mandate. Drawn up by Gertrude Bell, it was very generous towards foreign archaeologists, allowing them to receive and export a substantial share of the artefacts uncovered.

It all started to change in 1933, a year after the Kingdom of Iraq was granted independence. The ‘Arpachiyah Scandal’, involving Agatha Christie’s husband Max Mallowan, was the first step on a long and winding road towards an attempt to decolonise archaeology.

Max Mallowan spent the 1932-1933 season excavating for the British Museum at Arpachiyah, a prehistoric site in northern Iraq. At the end of the season the Director of Antiquities, German archaeologist Julius Jordan, divided up the objects found by various expeditions, as usual. He had carried out nearly all the divisions when the Minister of Education suddenly informed him excavators should only receive duplicates – objects the museum already possessed.

These new instructions meant that the excavators couldn’t actually get anything, ‘for the objects discovered by excavation in ‘Iraq were not produced in an age of mass production by machinery and cannot be duplicated’ (FO 624/1).

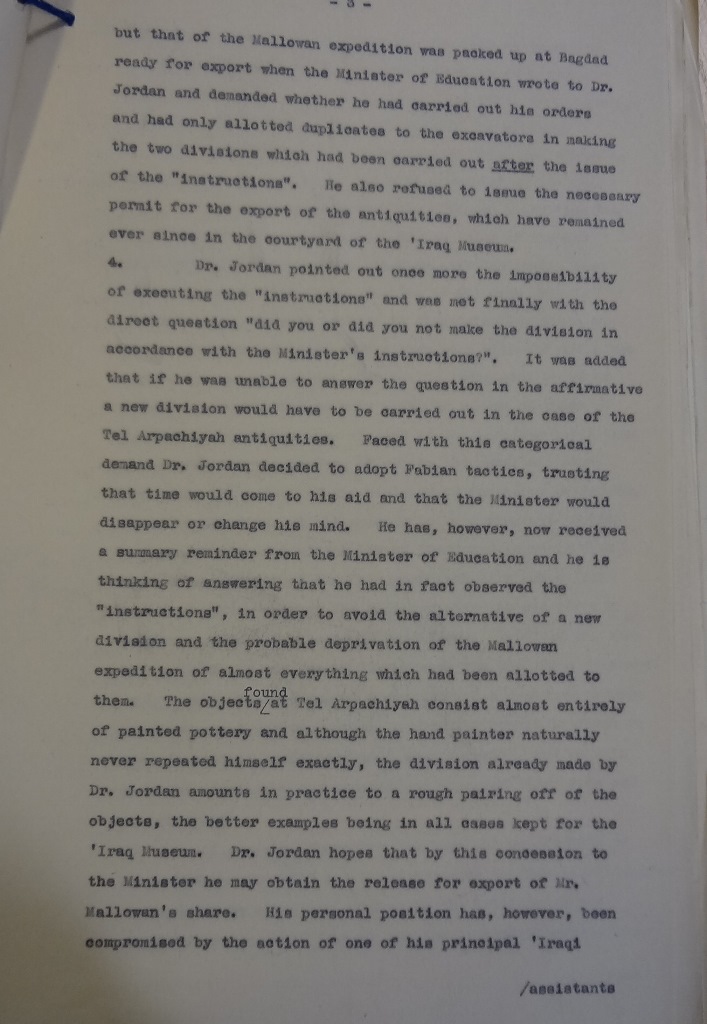

Jordan thought it was a mistake, and ignored the instructions. As Mallowan was about to leave, he was told the export permit needed to bring the artefacts back to the UK had been denied (FO 371/16923). The Minister asked Jordan a very direct question: ‘did you or did you not make the division in accordance with the Minister’s instructions?’ If not, it had to be done again.

Humphrys, the ambassador in Baghdad, reported to the Foreign Office:

‘faced with this categorical demand, Dr Jordan decided to adopt Fabian tactics, trusting that time would come to his aid and that the Minister would disappear or change his mind’ (FO 624/1).

On 2 August 1933, George Hill, Director of the British Museum, wrote to the Foreign Office, asking for help. He wanted the antiquities to be released, of course, but also

‘some explanation of the Minister’s reason for singling out this Expedition for such arbitrary treatment, in contravention of the Law of Antiquities, or, in the absence of a reason, some kind of apology’.

Hill also said a rumour was circulating in archaeological circles: inspectors were to be attached to foreign expeditions and a new law was being prepared.

The whole archaeological community reacted strongly to what became ‘the Arpachiyah scandal’. Leonard Woolley, also excavating in Iraq at the time, thought it was a strong statement from the Iraqi government, and one that could discourage foreign expeditions to return to the country. He was also particularly opposed to the idea of Iraqi inspectors joining foreign teams.

The Foreign Office Librarian, Stephen Gaselee, concurred:

‘the attachment of corrupt and ignorant inspectors to expeditions would mean that the expeditions would have to house and feed spies at great expenses to their funds’ (FO 371/16923).

The Counsellor in Baghdad, Ogilvie-Forbes, confirmed that the Minister, whom he described as ‘an obscurantist Shiah very ill-disposed towards foreigners and us in particular’, was working on a new law. He also reported that Jordan, who had seen it, had declared it ‘one-sided and rabidly nationalistic’ (FO 371/16923).

Although the Foreign Office explained that ‘Iraq was now an independent country, and, in the ultimate resort, had the right to enact whatever antiquities legislation she desired’, they were largely sympathetic to the archaeologists’ plea. In October 1933, Hill forwarded a memorandum outlining the concerns of the international archaeological community. Foreign archaeologists, they said, were not ‘gold-diggers’ nor ‘commercial companies working for profit’, but they had to get something in return for their work, otherwise they would never be able to get funding.

- Memorandum on the situation with regards to excavations in Iraq, October 1933 (catalogue reference: FO 371/16923)

- Memorandum on the situation with regards to excavations in Iraq, October 1933 (catalogue reference: FO 371/16923)

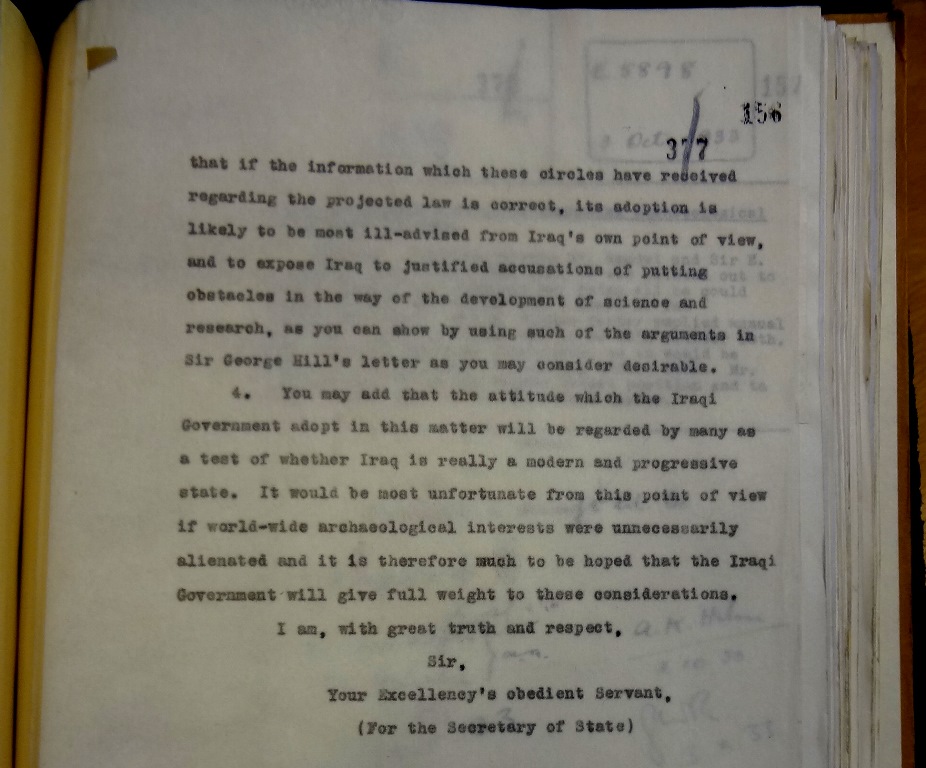

Humphrys was instructed to take the matter up with the Iraqi Government. George Rendel, the Head of the Eastern Department at the Foreign Office, emphasized the ‘serious injury which [the law’s] adoption would obviously occasion to the cause of archaeology in general’. He also thought that ‘the attitude adopted by the Iraqis in this matter [would] be regarded by many as a test of whether Iraq is really a modern and progressive State’ (FO 371/16923).

The Iraqi Prime Minister promised to show Humphrys the draft law before it was submitted to Parliament. By mid-November, however, the Iraqi government had resigned, and a new Minister of Education was appointed. On 18 November, Humphrys telegraphed that foreign expeditions could proceed as they would be working under the old law, and that he had been promised ‘no new antiquities law would be presented to Parliament without consulting foreign archaeologists’.

On 1 July 1934, Jordan wrote to Mallowan, explaining he couldn’t renew his excavation permit until the new law had been passed. He also sent a note outlining the main changes in the law which, he said, would ‘probably come into force during the season 1934/1935’. All expeditions were to consist of at least four people (the director, an architect, an epigraphist and a general archaeological assistant), and expected to host an inspector.

The most drastic changes concerned the division of antiquities. Under the new law, ‘all distinguished objects which [had] no parallel’ were to go to the Iraq Museum, the excavator receiving half of whatever was left; the excavator could only receive duplicates; ‘objects of gold and silver may be allotted to the excavator only by special permit of the Council of Ministers’ (FO 371/17871).

- Jordan to Mallowan, 1 July 1934 (catalogue reference: FO 371/17871)

- Jordan to Mallowan, 1 July 1934 (catalogue reference: FO 371/17871)

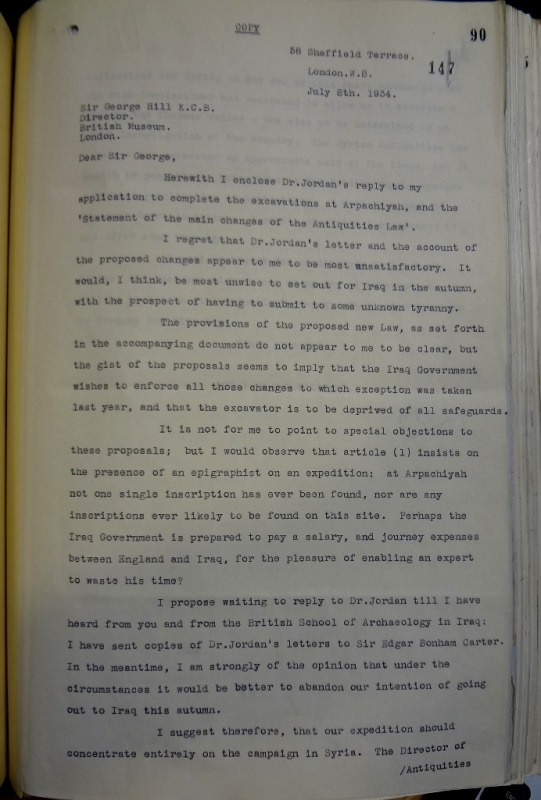

It was all a bit too much for Max Mallowan. He felt that if he accepted these terms, he would have to ‘submit to some unknown tyranny’. He didn’t understand, for instance, why he should have an epigraphist on his team at Arpachiyah – no inscribed object would ever be found on a prehistoric site. He decided he wouldn’t return to Iraq in the autumn and would focus on Syria instead.

Writing to the Foreign Office, George Hill complained the archaeological community hadn’t been consulted, ‘for the mere information that certain changes are to be made does not amount to consultation’. He agreed with Mallowan that the law should be more flexible in terms of the composition of excavation teams, and that the provisions for the division of the finds were ‘much too harsh from the point of view of the excavator'(FO 371/17871).

The sympathy of the Foreign Office then began to waver. Christopher Warner, a First Secretary, noted:

‘I don’t see what more “consultation” can reasonably be expected than to be informed of the proposed changes in the law and to be given several months in which to comment on them’.

Later in July, Oxford scholars sent a memo to the Foreign Office. They made it very clear they were opposed to all the proposed changes, which, they said, had been ‘conceived in so narrow a spirit of unintelligent nationalism that the Government [was] inevitably laying up for itself a legacy of universal condemnation from the learned world’.

By August, the concerns had become international. Hill explained that he had consulted colleagues in France, Germany, Italy and the United States and that they were ‘unanimous in describing the proposed changes as undesirable and obscurantist’, and warned that unless the attitude of the Iraqi government changed, the British Museum would be ‘unable to consider any further archaeological activity’ in the country.

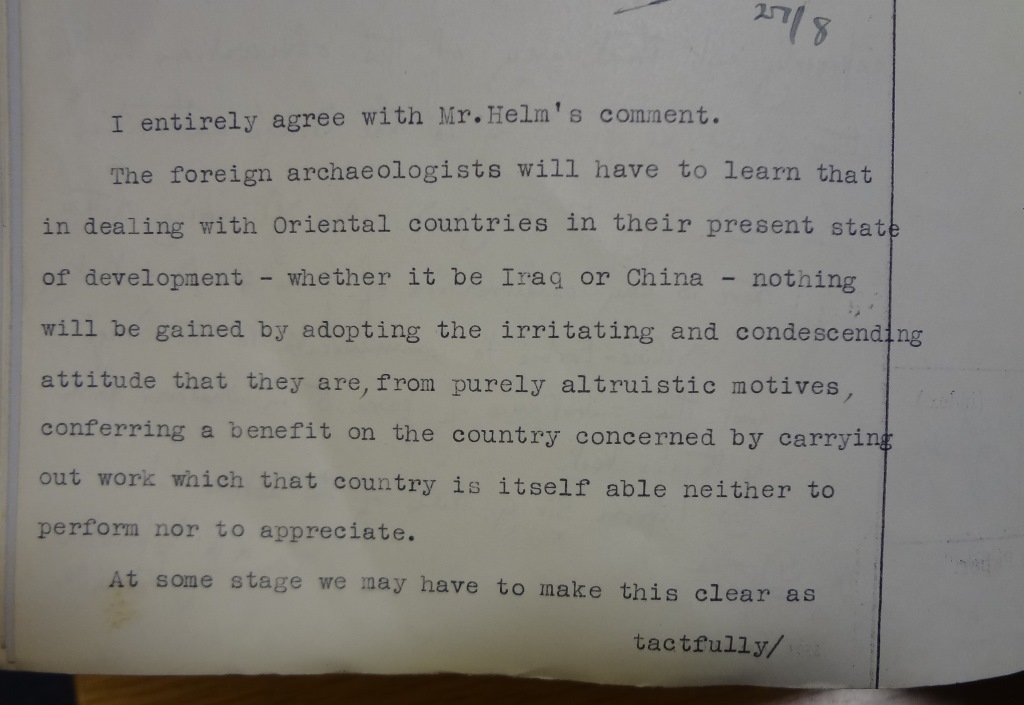

At the Foreign Office, the Eastern Department wasn’t impressed. Helm dismissed it as ‘a stupid letter’ while Sterndale Bennett commented:

‘the foreign archaeologists will have to learn that in dealing with Oriental countries (…) nothing will be gained by adopting the irritating and condescending attitude that they are, from purely altruistic motives, conferring a benefit to the country concerned by carrying out work which that country is itself able neither to perform nor to appreciate’ (FO 371/17871).

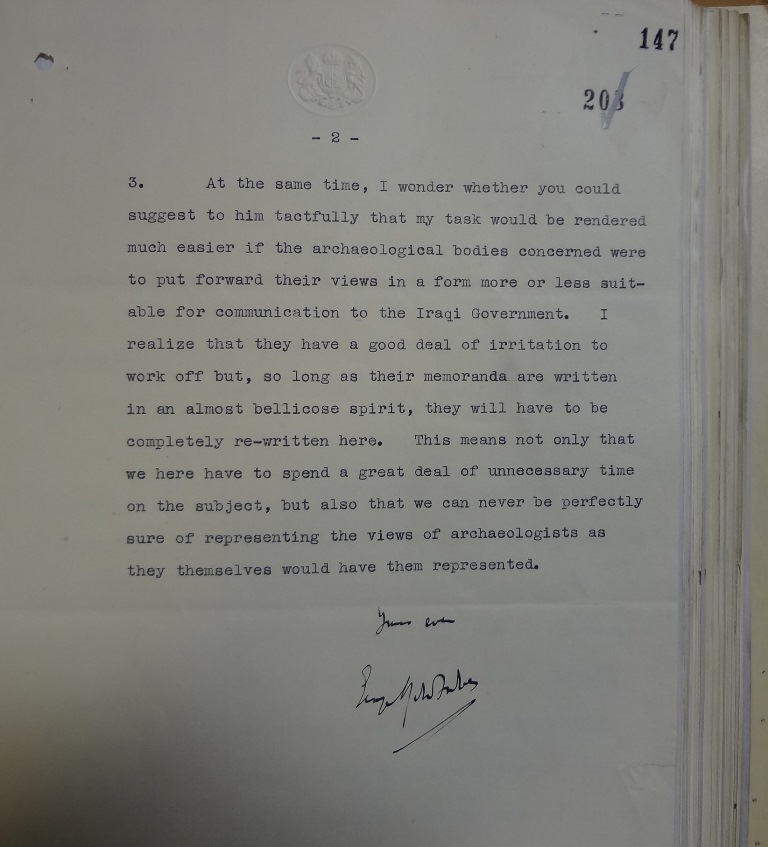

In Baghdad, Ogilvie-Forbes was also losing patience with the archaeologists. Not only were they all writing separately, which meant he had to talk to ministers over and over again, but their memos and letters were impossible to use. ‘I realize,’ he wrote, ‘that they have a good deal of irritation to work off but so long as their memoranda are written in an almost bellicose spirit, they will have to be completely re-written here’ (FO 371/17871).

By September it was clear the new law wouldn’t be ready for the 1934-35 season. In October 1934, Julius Jordan was replaced by Sati al Husri. For the first time, Iraq had an Iraqi Director of Antiquities. He immediately started drafting a new law, which was circulated in November 1935.

On 16 December 1935, the Archaeological Joint Committee held a meeting to examine the draft law. Helm, who attended on behalf of the Foreign Office, reported:

‘the general feeling was that the law was quite an impossible one, so impossible in fact that it was not worth the Committee’s while to examine or comment upon it in detail. The Committee felt that the only dignified line was to say so to the Iraqis, and indicate that the law was quite unworkable’ (FO 371/18946).

This may well have been the ‘dignified line’, but it was most unlikely to help the archaeological cause.

The Antiquities Law was finally promulgated in April 1936. Article 49, laying out the provisions for the division of the finds, stipulated that archaeologists would receive half the duplicates, the objects the Museum didn’t want and could make casts of the others. The new Ambassador, Sir Archibald Clark Kerr, commented:

‘though possibly not framed in such generous and accommodating terms as many archaeologists would desire, this article is still, I believe, more favourable to their interests than similar articles in the laws of many countries’ (FO 371/20011).

For Sati al Husri, the aim of this new law was to ‘have a record of the antiquity treasures available in Iraq for the purpose of preservation from destruction and damage’ (FO 624/5). At a time when Iraq is reclaiming and embracing its ancient past again, we can only wish that the spirit of this law may prevail.

I wonder what would happen if archaeologists came to Britain in the same time period and were allowed to export some of our history to their own country.

Thanks Juliette – this is a fantastic piece!

Thanks Jamie, glad you liked it!

Thank you for a great article.

Article 49 of the new Antiquities Law stated, that all antiquities found was the property of the Iraqi Government, but excavators should be given the right to make castings, half of the duplicate antiquities, and antiquities that the Iraqi Government could dispense with. In 1937 the Sixth Committee of the League of Nations agreed on the “International Statue for Antiquities and Excavations”, which similarly stated that antiquities found should be set apart to complete the collections of the museums of the finds’ country of origin, although the excavator could be rewarded with a share of the finds, which should consist of duplicates and dispensable antiquities.

Cf. chapter five in: Bernhardsson, Magnus .T. 2005. Reclaiming a Plundered Past: Archaeology and Nation Building in Modern Iraq. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Great article and summary of what went on post Gertrude Bell! I can never get over the sense of entitlement of these archaeologists who would never reciprocate these privileges to foreigners in their own country.

I’m currently studying and trying to understand the period during which Bell drew up the 1924 law, but I can’t find a copy of this law anywhere. Would you have a copy? I found references to it, naming it as a publication issued in English by the “Iraq Government Press” entitled “Antiquities Law, 1924”, but I can’t locate it. There is no copy in the British Library nor in the National Archives as far as I can see. If you have any pointers, it would be greatly appreciated!