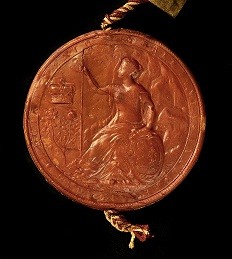

C 110/26, reverse of Queen Anne’s 1709 seal, showing the rose of England combined with the thistle of Scotland

This August marks the 300th anniversary of the death of Queen Anne, the last of the Stuart monarchs, and the first sovereign of Great Britain. There is currently an accompanying document display in the Keeper’s Gallery here at Kew.

Queen Anne succeeded to the throne in 1702 on the death of her brother-in-law William III. Her father, the Catholic James II, died in France in 1701, having been overthrown by the Glorious Revolution. Anne was 37 years old when she became queen, and even at her coronation suffered from a bad attack of gout and had to be carried to the ceremony in an open sedan chair.

Anne never enjoyed good health, and her many pregnancies that ended in miscarriages greatly weakened her. She became pregnant eighteen times, but only one child lived, William Duke of Gloucester. He died in 1700, aged only 11, it is thought of hydrocephalus or ‘water on the brain’ (details relating to his funeral can be found in LC 2/14/1). While Anne had been married in 1683 to Prince George of Denmark, a chronic asthmatic, he was very much regarded as a nonentity. The soldier prince consort died in 1708 (records of his funeral can be found in LC 2/16 and LC 2/17).

On 1 May 1707 England and Scotland were combined into a single kingdom with Anne at its head (see C 204/92 for the ‘Act of Union’ of the two kingdoms). One British Parliament would meet at Westminster, and there would be a common flag, coinage and customs union. Politically, Anne’s reign was marked by the development of the two-party system, with Whigs and Tories competing for power. Although the Whig Junto became more powerful during the ensuing War of Spanish Succession, there was a major shift in 1710 to the (anti-war) Tories under the leadership of Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford, which lasted until her death.

Anne personally disliked the Hanoverian House of Brunswick, whom the succession had been settled on by act of Parliament in 1701 (over the claim of her half-brother, James, known as ‘the Pretender’). The queen was unforgiving of the Elector Georg Ludwig (the future George I) right up to the day she died, having been rejected in marriage by him in 1680. His mother, the Dowager Electress (daughter of Elizabeth Stuart, the ‘Winter Queen,’ and sister of Prince Rupert of the Rhine), whose greatest wish it was said was to have ‘Sophia Queen of Great Britain’ inscribed on her tomb, narrowly missed her ambition when she died suddenly (aged 83) on 8 June 1714, just a few weeks before Queen Anne. On 27 July Anne finally decided in favour of George and the Hanoverian Succession.

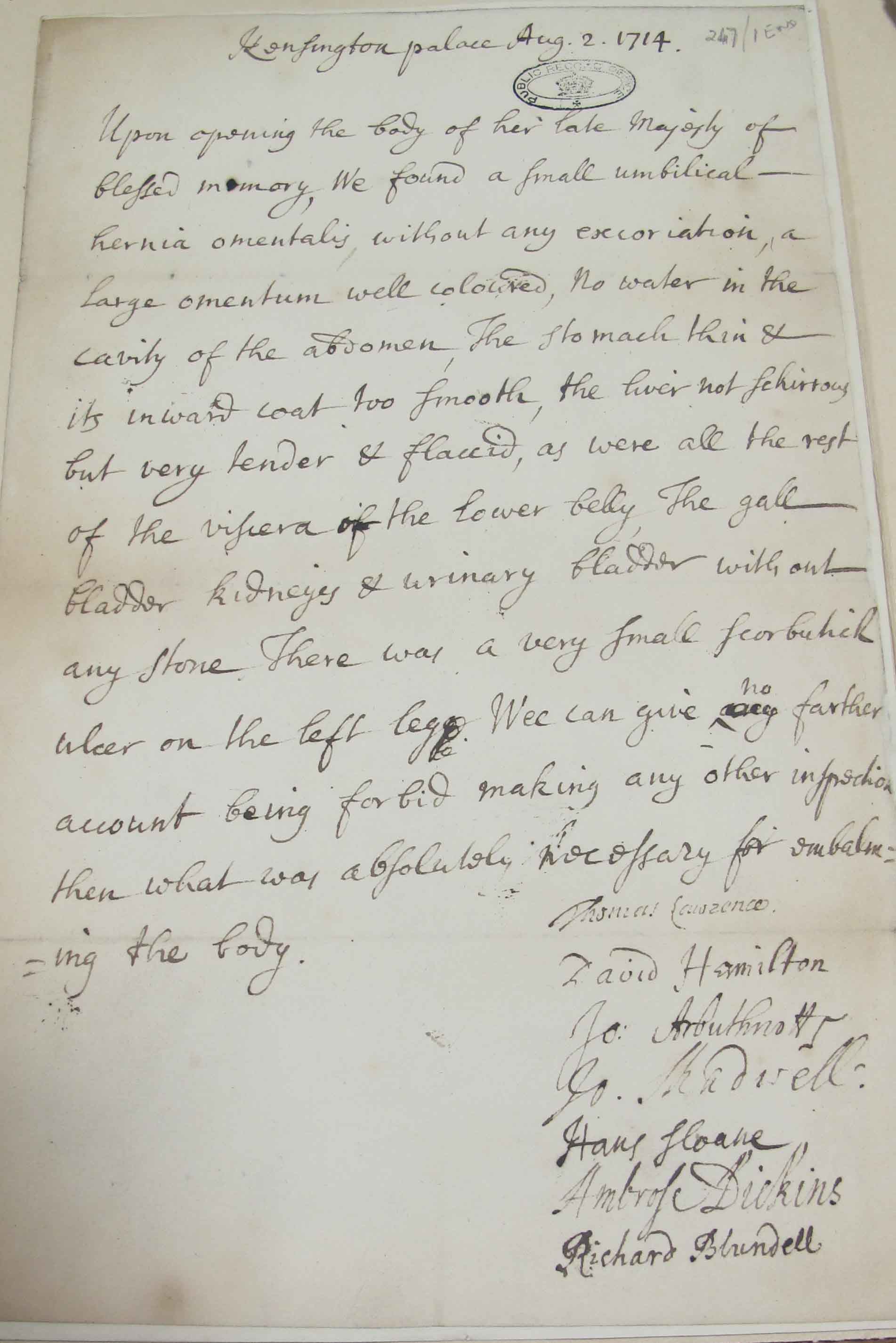

Towards the end of her life Anne suffered increasingly more from gout, and could hardly walk. Having been taken ill on the morning of 30 July she died around 7.30 a.m. on 1 August 1714 at Kensington Palace, her body being so swollen with dropsy that she had to be interred in a vast square shaped coffin. She was buried in the same vault beside her husband and children, in Henry VII’s Collegiate Chapel of St Peter, Westminster Abbey on 24 August. John Arbuthnot, one of her doctors thought her death was a release of life from ill-health and tragedy; he wrote to Jonathan Swift, ‘I believe sleep, was never more welcome to a weary traveller than death was to her’.

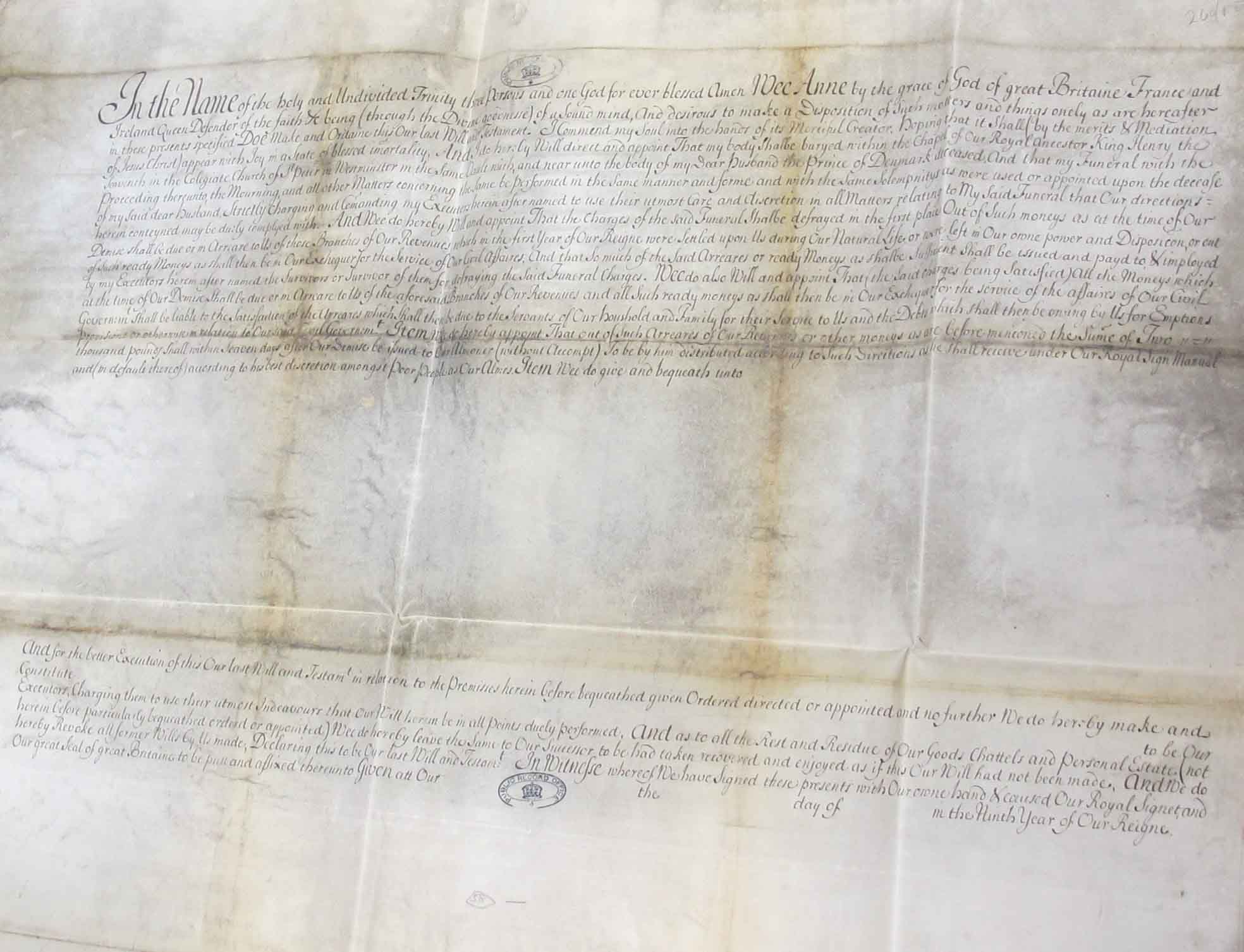

Doctor Thomas Lawrence who performed her autopsy, and who delivered a paper ‘Upon the Observations of the Opening of the Queen’s Body’, discovered a small umbilical hernia before embalming her. Amongst those in attendance was her physician Hans Sloane, the future founder of the British Museum. Queen Anne died intestate, having refused to sign draft wills prepared for her. Interestingly, at the meeting of the Privy Council at St James’s Palace on 3 August 1714, two incomplete draft wills were read out and referred to a committee. Both drafts PC 2/85 (pp. 25-27) were actually found in the Queen’s Closet at Kensington (scene of the great ‘falling out’ with her favourite Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough in 1711). The second of these wills from her regnal year ‘nine’ (1710-1711) ‘The Last Will and Testament’, can be found in PC 1/2/260.

And what of Queen Anne’s legacy? Sarah Churchill’s prejudicial recollections persuaded many biographers that Anne was a weak and hesitant woman, beset by bedchamber quarrels, deciding high policy on the basis of personality. Other critics (such as High Church Anglicans, Jacobites or Protestant Dissenters) satirised her as ‘Brandy Nan’ for her fondness for the bottle.

In the opinion of many historians however, she wielded considerable power, yet time and again she had to capitulate. Others conclude that Anne was often able to impose her authority, even though her reign was marked by an increase in the influence of ministers and a decrease in the influence of the Crown. She attended more Council meetings than any of her predecessors, and presided over an age (as personified by the work of John Vanburgh and Daniel Defoe) of artistic, literary, economic and political advancement that was made possible by the stability of her rule. Indeed, Anne was internationally so well regarded that a Russian Bestuzev at the Hanoverian Court, was sent to report the queen’s death to the Tsar (Peter the Great) who ordered six weeks of mourning (SP 91/8/26).

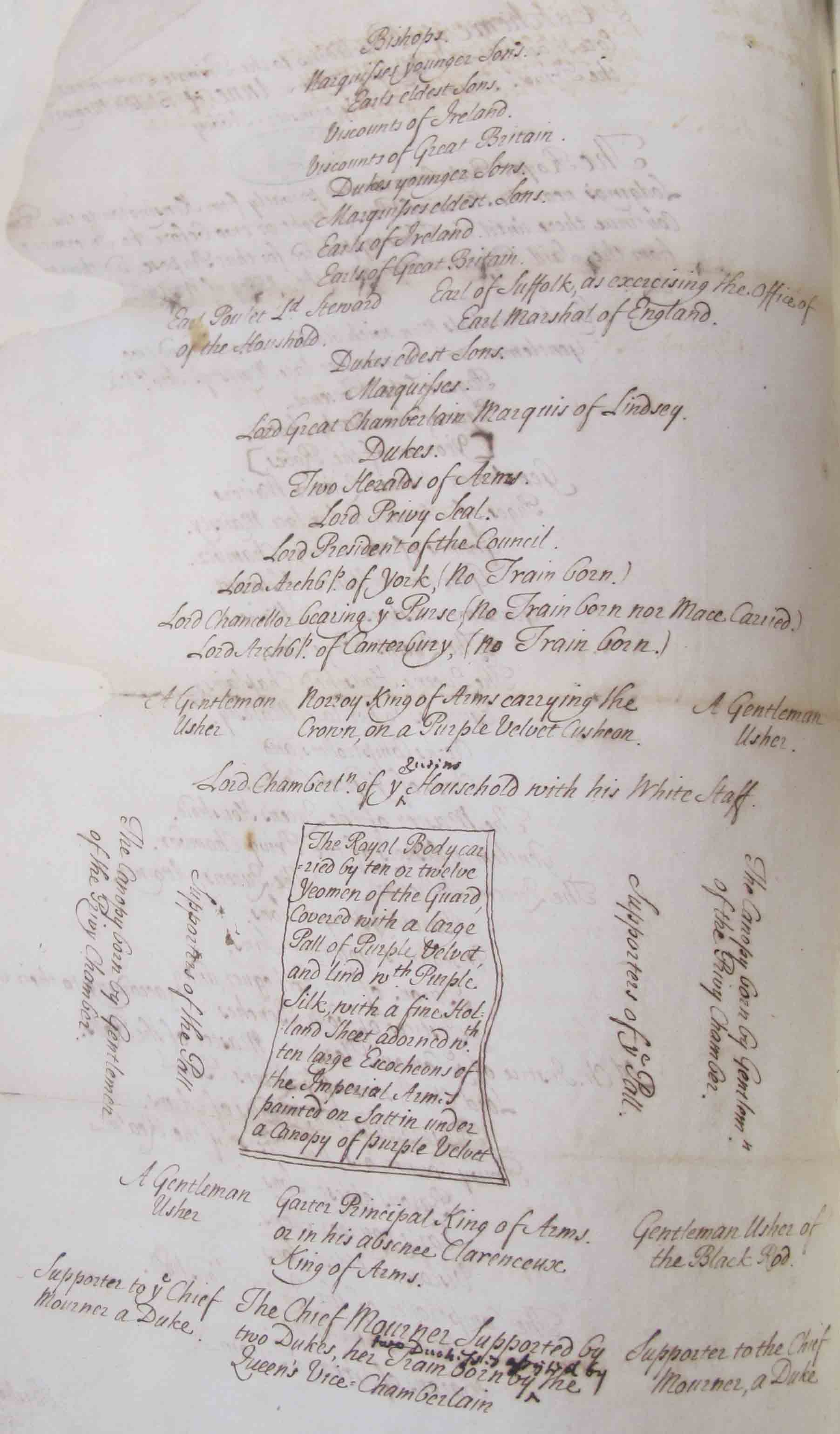

PC 1/2/256, ‘Lying in State’, plan for the funeral procession and service of Queen Anne at Westminster, 14-16 August 1714

Ironically, while Queen Anne ultimately brought parliamentary union to her kingdoms she failed to give them an heir.

She was also the last Monarch to attend the meetings of the Treasury Board (see T 29), which looked at virtually every proposal in government both at home and overseas and of course the Royal income!.

Whilst Anne was not really a Queen to match against the calibre of Elizabeth I, she appears to have accepted her responsibilities as a monarch of Great Britain in far better faith and honesty and humility, than many who came before and after her ever did! I’m sure that many women looked up to her and quite possibly she may have forwarded women’s suffrage towards equal equality over a time period, within each generation of mainly male dominated societies? She did her best – what more can one ask of a queen?

Does anyone know of a connection, however tenuous, between the Clitherow family of Boston Manor, Brentford, Middlesex, and Queen Anne. I have a tortoiseshell comb made in Port Royal, Jamaica, sometime between 1671-1692, which, family legend has it, was a gift to a Mrs Clitherow from Queen Anne.

Any positive help would be most gratefully received!

Hi Peter,

Unfortunately we’re unable to help with family history requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

I am doing some research onthe group Jamaican tortoiseshell combs from 1671 – 1690 and would be very interested in any information or images you could let me see of the comb you mention in the above comment

many thanks