Disability History Month runs from 22 November to 22 December. To mark it, The National Archives is publishing a series of blogs focusing on aspects of disability which appear in our records.

The National Archives holds the records of central government and the law courts. Our records, therefore, are more likely to reflect the interests of government rather than the lived experiences of people with disabilities.

It is well known that historic terminology can be offensive to modern ears. But it can also be informative to reflect on the language used in previous centuries, as it often held meaning that may have since been lost and with many words becoming increasingly pejorative through casual use in the playground and in everyday discourse.

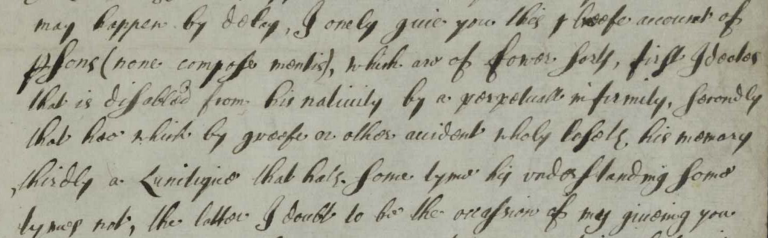

For example, prior to modern times there was a clear distinction between the terms ‘idiot’ and ‘lunatic’, which is explained in this letter of 1663 below. The correspondent suggests there are four different types of people who are ‘none compos mentis’, but then goes on to list just three: ‘first Ideotes that is disabled from his nativity by a perpetuall infirmity, secondly that hee which by greefe or other accident wholy loseth his memory, thirdly a Lunitique that hath some tyme his understanding some tymes not’. The changeable nature of lunacy, as defined here, reflected the waxing and waning of the moon after which the affliction was named.

Extract from letter from W. Knasbrough to Henry Bennet, Earl of Arlington, Secretary of State, 6 Jan 1663. Catalogue ref: SP 29/67, f.35

What is striking in our records is that the choice of language was usually made by the non-disabled and the views of people with disabilities did not usually feature in any classification. One exception is the self-description employed in wills, where the writer often wanted to make it clear that they were mentally capable of declaring their final wishes about the disposal of their property, while acknowledging that they were physically challenged in the face of imminent death.

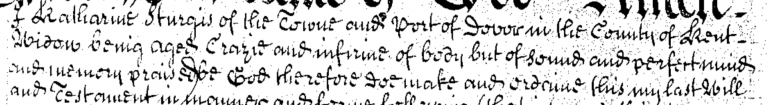

In 1717, Katharine Sturgis of Dover described herself as ‘being aged crazie and infirme of body but of sound and perfect mind and memory praised be God’. On the face of it, this is a contradictory statement, but it is clearer when you know that ‘crazy’ can mean full of cracks or flaws (think of crazy paving), and therefore denotes that she considered herself physically frail.

Extract from register copy of will of Katharine Sturgis, written 1717 and proved 1720. Catalogue ref: PROB 11/579/71

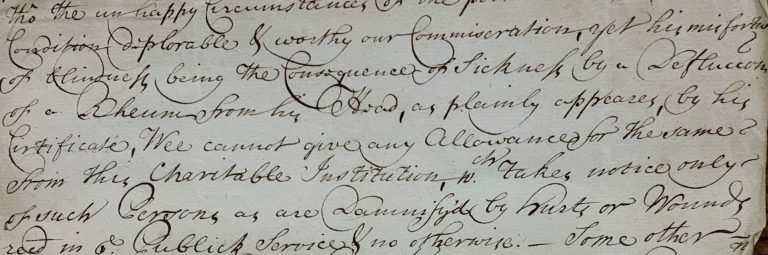

Perceptions of disability changed over the period covered by our records. As explained on the English Heritage History of Disability website, disability moved from being perceived as an affliction brought about by divine judgment and began to be seen as a medical condition by the 17th century. Even so, this letter written in 1703 about a sailor who was blind as the result of an illness has echoes of hell-fire in its use of the legal term ‘damnified’. The sailor was judged ineligible for a charitable payment from the Chatham Chest because he was not ‘damnify’d by hurts or Wounds received in the Publick Service’.

Letter concerning George Whitehead, a blind seaman, 7 Jul 1703. Catalogue ref: ADM 106/567/4

The state took a greater interest in the disabilities affecting its citizens in the 19th century, when the need to quantify the population resulted in the first national censuses. From 1851, questions were asked about disabilities, asking about blind and deaf individuals at first and then, from 1871 onwards, exploring the numbers who were ‘imbeciles or idiots’ or ‘lunatics’, indicating that the distinction between these terms continued to be relevant. In 1911, the questioning went into greater detail, enquiring about the age at which each named person had developed the disability.

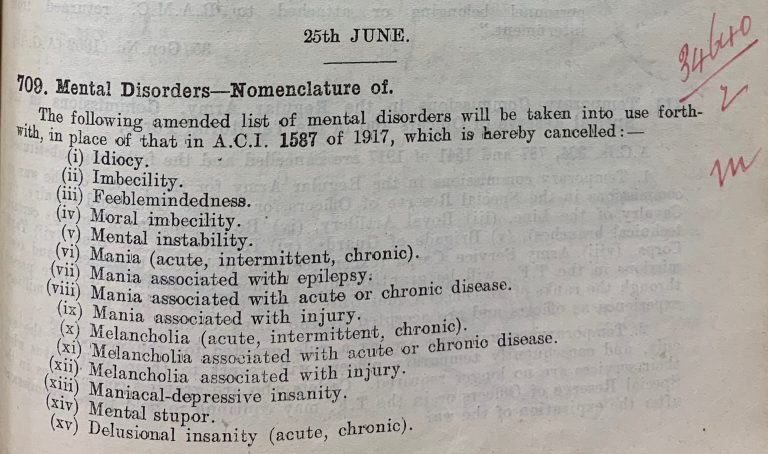

These attempts at quantification were accompanied by an attempt at more granular classification, particularly of mental illnesses and learning disabilities. This is exemplified by an Army Council Instruction of 1918 (revising one issued in 1917) which required medical officers to classify ‘mental disorders’ as one of 27 different types, for example distinguishing melancholia associated with injury from melancholia brought about by acute or chronic disease.

I found it interesting that none of the 27 classifications was for ‘shell shock’, even though this term was developed by medics during the First World War and has perhaps come, more than any other term, to define the mental trauma caused by that war.

Army Council Instruction no.709, 25 June 1918. Catalogue ref: WO 293/8

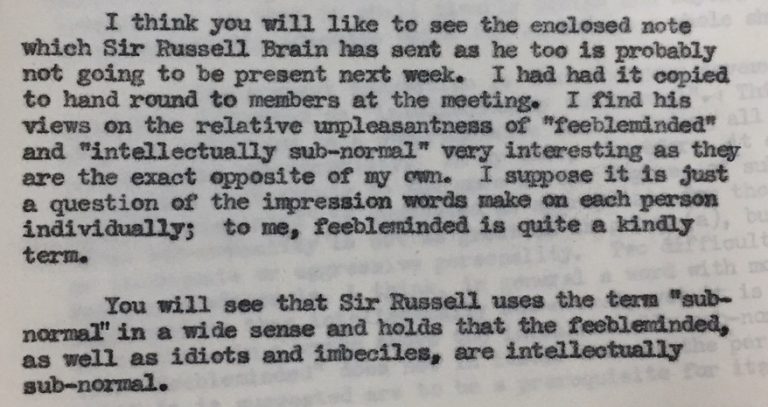

There was still a clear overlap between clinical diagnostic analysis and more emotive terms used in everyday language. We see this in the 1956 papers produced by the Royal Commission on the Law Relating to Mental Illness and Mental Deficiency, where terminology was under discussion. The Secretary to the Commission wrote at one point, ‘I find his views on the relative unpleasantness of “feebleminded” and “intellectually sub-normal” very interesting as they are the exact opposite of my own. I suppose it is just a question of the impression words make on each person individually; to me, feebleminded is quite a kindly term.’

Letter from Miss H M Hedley, Secretary to the Commission, to Dr Thomas, 16 Feb 1956. Catalogue ref: MH 121/7

This blog is obviously not a thorough overview of the use of historic language relating to disabilities, but I hope this selection of documents helps to demonstrate how fluid language has been, with the meaning and implications of certain words changing over time and, no doubt, continuing to do so.

Our Research Guide on Disability History explains some of the key sources available at The National Archives and how to access them. The other blogs in this series, together with those we have published in previous years, will be found under the tag Disability History Month as they are published.

Fascinating. This offers so many insights to the changing role of language and classification in labelling and stigmatising

The problem is that immediately after a term is introduced to describe or define anything that is seen as different, that word is taken over by society to use in a derogatory way. The change begins in playgrounds, pubs and all forms of comedy. So any term which starts out as a simple way to describe a different appearance, behaviour or household situation inevitably soon becomes abusive. ‘Bastard’ initially was simply a description, as in “King William the Bastard” in the 11th century. ‘Negro’ from the Latin for ‘black’, was a polite descriptive classification until it was subverted into the awful N.. word. ‘Sub-normal’ simply means not reaching the norm or average. (Latin ‘sub’ meaning ‘under’ or ‘below’), but I am with the writer who now finds that term much more offensive. Words change, and it can be hard to keep up. It’s upsetting for both sides when a word hurts and offends, often when there is no such intention. It is negative *usage* that loads the words with negative meaning, so it will always happen. Words that sound terrible to the young may feel innocuous to the old who, maybe decades before, experienced its introduction as simply a defining term.