I don’t watch too much television now, but back when responsibility was light and life was easy, ‘Porridge’ re-runs often found their way into my viewing diet. Being far younger than I am now, and not having spent a stretch behind bars myself, I didn’t much question the authenticity of ‘HMP Slade’, architecturally at least. Maybe I should have. Wikipedia reveals that Slade’s exterior was in part footage of an old brewery off the A505, whilst some interior shots were filmed in Shepherd’s Bush Police Station – so, not a real prison then.

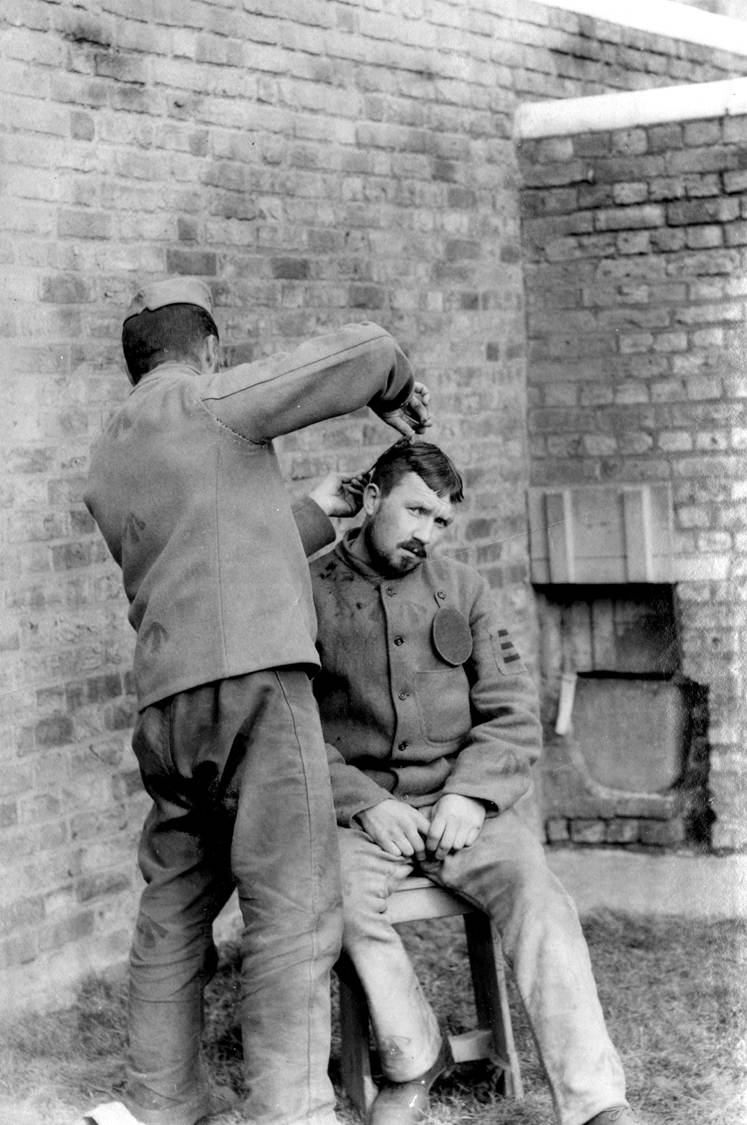

Photograph interior Wormwood Scrubs Prison cutting hair of prisoner (catalogue reference: COPY 1/420/169)

The show’s artistic licence didn’t end there. Lennie Godber (Ronnie Barker’s Brummie cellmate played by actor Richard Beckinsale) used to sport a fine head of almost shoulder-length hair. In 1974 (the year ‘Porridge’ first aired on BBC1) UK prison rules required convicted prisoners to ‘shave or be shaved daily, and to have his hair cut as may be necessary for neatness.’ 1 Now I’m not sure Godber’s mane could be considered neat, but perhaps Richard Beckinsale didn’t fancy chopping his locks for the role?

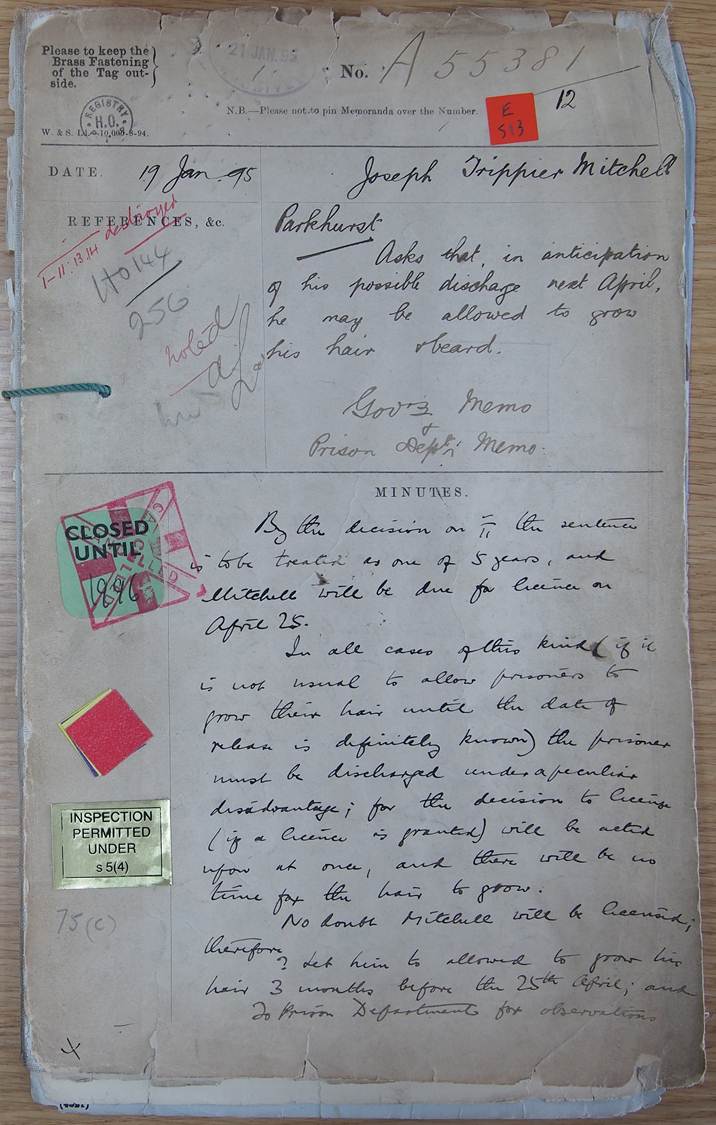

Rewind almost 80 years, and unfortunately for Joseph Trippier Mitchell, a gentleman convicted of forgery and enjoying a ten-year stay at Her Majesty’s pleasure in Parkhurst Prison in 1895 (HO 144/256/A55381), there was not a scriptwriter in sight. His personal hygiene regime was placed firmly out of his control.

Permission to allow prisoners a certain time to grow their hair and beards before discharge (catalogue reference: HO 144/256/A55381)

This document, minuted by various Prison Department officials, details Mr Mitchell’s petition to the Secretary of State for permission to grow his hair in advance of his anticipated early release on the grounds of good behavior. Of particular interest is his rationale for this request:

‘His present closely cropped condition would not only cause much discomfort to the members of his family and to himself, but it could not fail to have a very prejudicial effect upon his chance of obtaining early employment and would probably result in two or three months enforced idleness.’

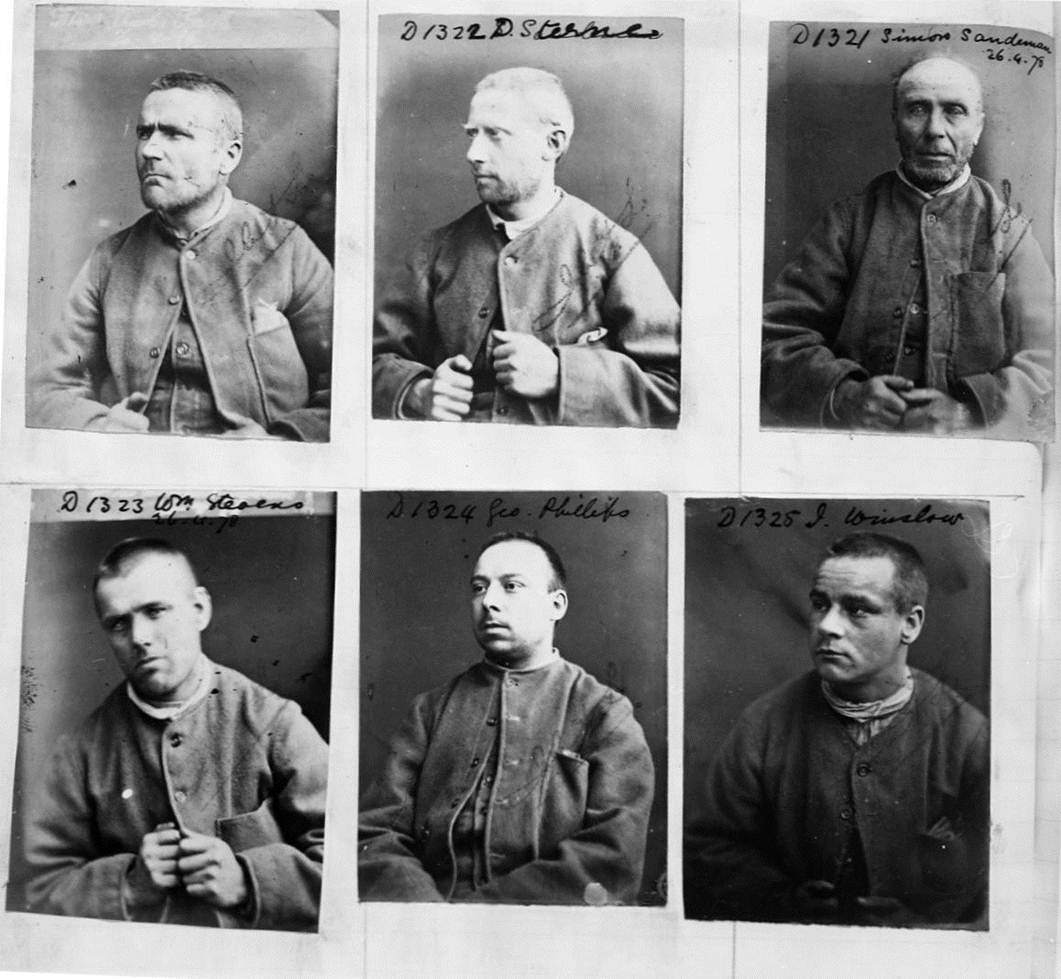

Mitchell had a point. By the 1890s, the long, slightly unkempt male coiffure characteristic of the Romantic period was no longer in vogue. It had since been replaced by short and neat (but not cropped) styles with a touch of well kept facial hair; the look of choice for the man about town as demonstrated by the photograph below (COPY 1/433/740).

![Photograph of John Hawke, [Esquire], Lapford House, Gloucester Road, New Barnet, 3/4 face (catalogue reference: COPY 1/433/740)](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/01155257/COPY1-portrait1.jpg)

Photograph of John Hawke, [Esquire], Lapford House, Gloucester Road, New Barnet, 3/4 face (catalogue reference: COPY 1/433/740)

Six prisoners, Pentonville Prison (catalogue reference: PCOM 2/99)

So what was the outcome? Well, the general consensus of the officials looking at his case was that Joseph Mitchell was being rather presumptuous about his release date. Being only five years into his ten-year sentence, his release for good behaviour was a privilege and not a right. Naturally, they did not want to give the wrong impression by allowing him to begin cultivating his locks for release: ‘ a prisoner interprets the permission to grow it as a sure sign he will be released and it is then hard to disappoint him’ (HO 144/256/A55381).

In the end however, Mitchell’s petition paid off, not just for him, but for all male prisoners. As a result of his request, the rules were amended to give prisoners license to grow their hair six weeks prior to their scheduled release date, sparing them and their families from ‘being brought under notice to their detriment’ (HO 144/256/A55381).

As I hope you may now appreciate, something as routine as a visit to the barbers can take on an entirely new significance when placed in a different context. Sticking with prisons, in the next installment we’ll take a look at cuts in custody through the lenses of gender and religious belief.

Notes:

- 1. The Prison Rules 1964 – Statutory Instrument Number 388. ↩

The BBC were refused permission to record in a real prison, see file HO 303/47: “BBC TV comedy ‘Porridge’ : request to film some scenes in prison; permission refused as prison policy did not allow facilities for fictional films or programmes”.

Makes sense – but somehow quite disappointing to know that HMP Slade was a cross between an old brewery and a Police Station! Has the law changed now? Location fees can be quite lucrative I hear…

But not sufficiently lucrative to outweigh the cost of relocking if a real key is accidentally shown I would suspect.