As part of The National Archives’ commemoration of the centenary of the First World War we have been running a project to catalogue some of the private correspondence of key British diplomats of the period.

These collections, held in record series FO 800, are a gold mine for researchers interested in British foreign policy, offering the personal and private views of leading figures, which often present a very different picture to that in the official Foreign Office records. They also contain many extraordinary stories which have until recently remained hidden. In a previous blog I highlighted one of these, Kaiser Wilhelm II’s penchant for pyjamas!

Over the last week the cataloguing of the papers of Lord Curzon has gone live on the catalogue, providing insights into his time as Parliamentary Under-Secretary in the 1890s and as Foreign Secretary from 1919 to 1924. This latter period was a crucial time in which Britain played a leading role in the rebuilding of Europe following the First World War.

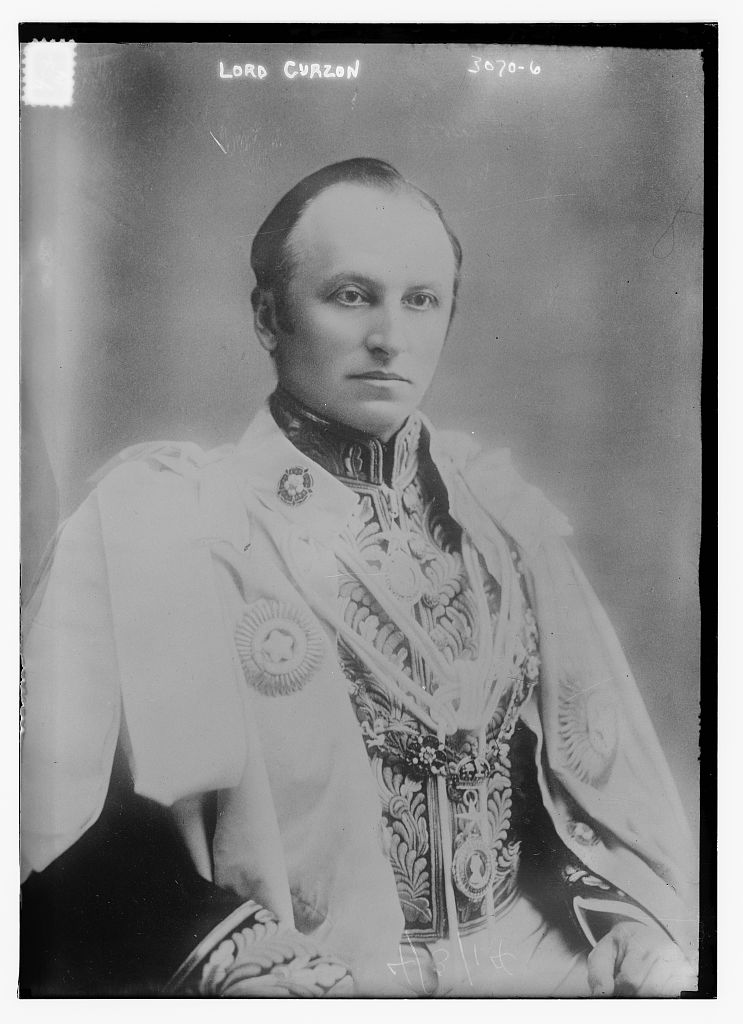

Lord Curzon (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-B2- 3070-6])

In 1923 it was announced that Crown Prince Hirohito, heir to the Japanese throne was to marry, and the thorny question arose as to whether the King and Prince of Wales should send gifts.

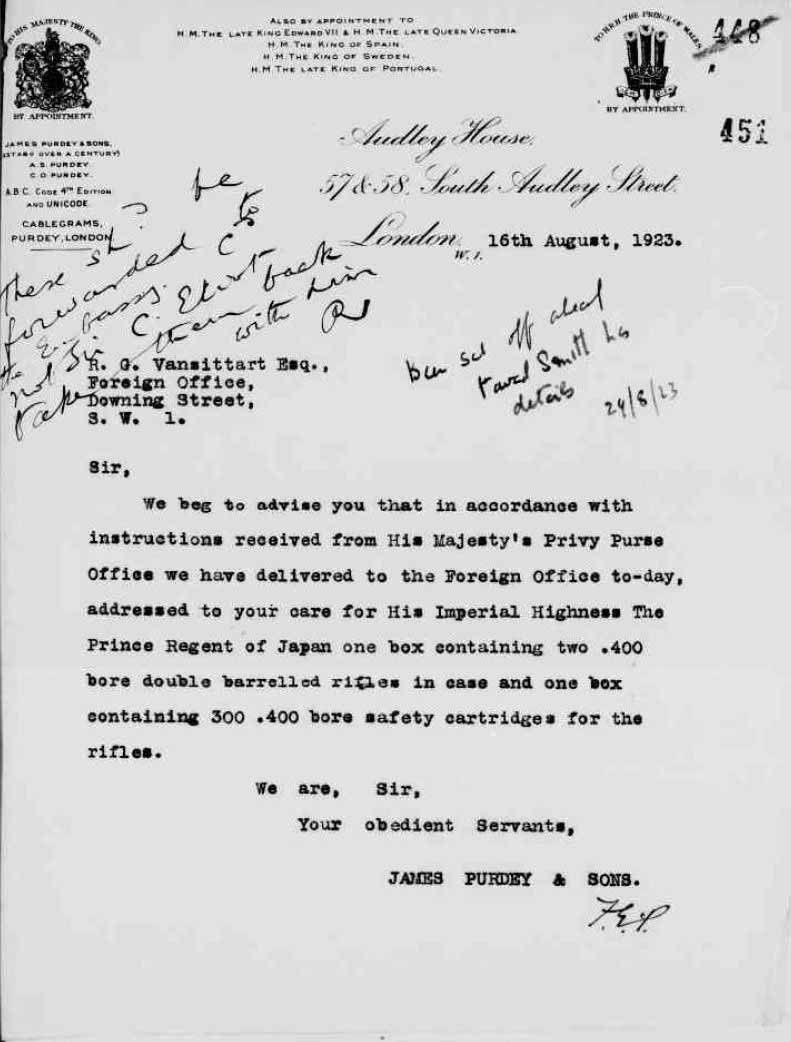

Letter from James Purdey & Sons on delivering the guns to the Foreign Office (catalogue reference: FO 800/155/128)

After much debate it was decided that the King should send a gift to the Crown Prince. The British Ambassador, Sir Charles Eliot suggested that ‘sporting rifles would be quite a suitable present’ and the high-end gunmaker Purdey’s were commissioned to make two rifles.

When the bill came in it caused consternation in the Foreign Office: the rifles were to cost £340, a very considerable sum. Curzon’s private secretary Robert Vansittart wrote to Eliot saying that ‘three hundred and forty pounds seems a lot for a pair of rifles, and I hope the Prince Regent is a keen sportsman. Is he?’ Before Eliot had a chance to respond Curzon minuted angrily:

‘I think the price quite absurd, and I am sure the poor little man is not a sportsman’ (FO 800/155/126)

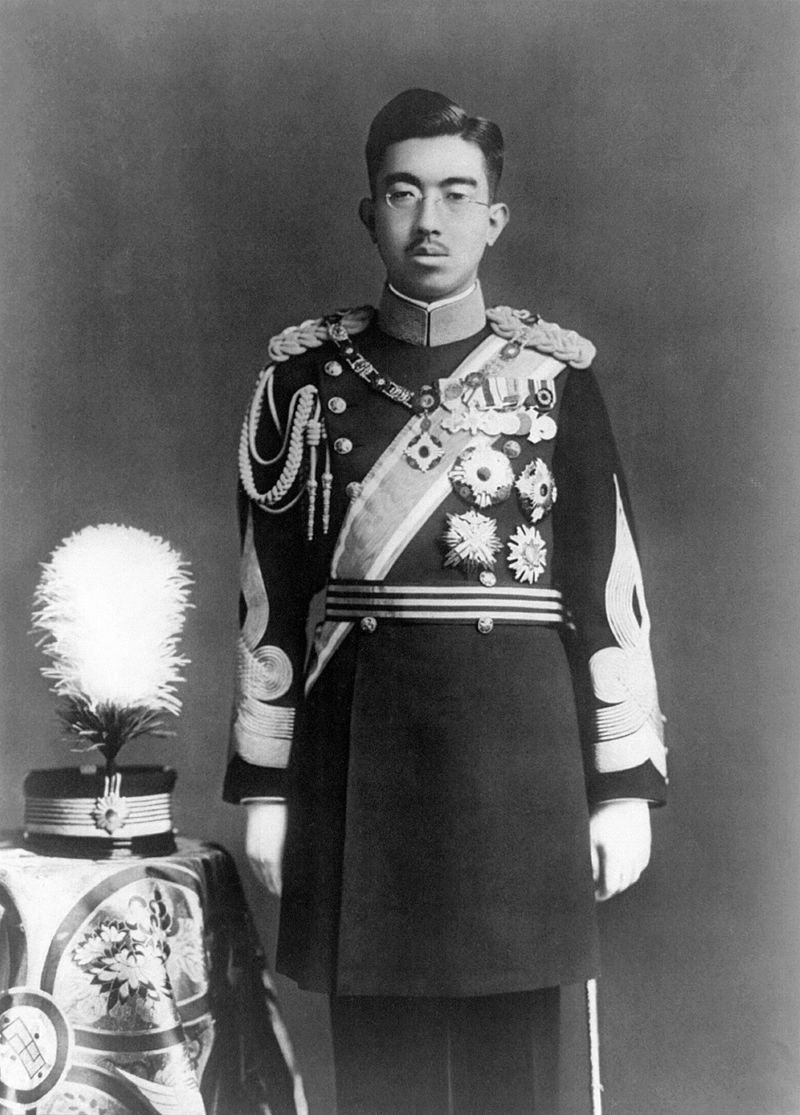

Emperor Hirohito (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-USZ62-40522])

Despite Curzon’s outrage the gift of the rifles went ahead, and attention quickly turned to the question of whether the Prince of Wales needed to send a gift as well. Crucial within this was the fact that the Prince of Wales had recently visited Japan, and had been received by the Crown Prince. As Eliot candidly noted:

‘I am certainly very strongly of the opinion that the Prince of Wales ought to give a good present. [He may have been really bored in Japan but] the Japanese cling to the fiction that the heirs to the two thrones are great personal friends.’ (FO 800/155/127)

The Foreign Office grudgingly accepted the advice of the Ambassador and in addition to the rifles Crown Prince Hirohito also received a gold cigar box from the Prince of Wales. The official Foreign Office correspondence reveals that the presents were gifted with great ceremony by Eliot, without a hint of the wrangling and bitterness with which they had been chosen (FO 371/10304).

Other examples provide an insight into the gossip that spread through the diplomatic circles, whether by conversations or private communications. One of the more remarkable came from Lord Derby, the British Ambassador in Paris, writing to Lord Curzon in May 1920. He related an extraordinary story he had just heard about the French President, Paul Deschanel:

‘The President of the Republic had a marvellous escape last night. He was going to Montbrison and in trying to open a window fell out of train which was going at sixty kilometres an hour. He telephoned himself to say that he is absolutely unhurt’ (FO 800/153/77)

Paul Deschanel (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-B2- 2640-3])

Some of the gossip was less directly connected to diplomacy, but still points to the information networks developed by British diplomats. In June 1923 Sir Charles Marling, the British Minister in The Hague, was sending details of the Dutch Queen’s travel arrangements. As an aside he remarked that:

‘Her Majesty crosses to England arriving at Gravesend on the morning of the 27th by the “Batavier V”, a Dutch boat, the crew of which makes a pleasing competence I am told by cocaine smuggling’ (FO 800/156/35)

Quite how Marling was aware of the drug smuggling tendencies of the crew of this ship is not clear, but it provides a tantalizing insight into the personal worlds of these men.

The new cataloguing of the Curzon correspondence will enable researchers to make much better use of this fascinating collection of papers and hopefully, a century on, shed new light on the process by which peace was built in the years after the end of the First World War. At the same time it also reveals numerous amusing and unknown stories and personal details that allow us to get a better understanding of the men behind this process, highlighting that even diplomatic history is ultimately the history of people.