African art and design is currently attracting a lot of interest, with exhibitions at the British Library and the William Morris Society to name but two. Perhaps surprisingly for an archive of government documents, The National Archives holds a large number of textile designs intended for export to West Africa. Strikingly fresh and vibrant, they form an unexpected contrast with the Victorian and Edwardian patterns around them.

Registered by the Calico Printers Association, 17 September 1918 (catalogue reference: BT 52/3224 152353)

We hold these textiles because they were registered for copyright under a series of Acts of Parliament from 1839 onwards. The textile samples, pasted into huge leather-bound volumes, and later stored away in archival boxes, were submitted as part of the copyright application process. Our online guide on registered designs has more information.

These samples are an invaluable resource for researchers, with potential to add to our understanding of the textile trade with West Africa. We can see which designs were being exported, and the registers that correspond with the samples tell us which companies were involved.

This material illuminates the way in which various genres of West African design were appropriated and mass-produced in Britain before being sold back to West Africa. They raise fascinating questions relating to authenticity and pastiche. Did the manufacturers make straightforward copies of existing African designs, or did they produce new ones? If the designs were new, did they help create a European-African aesthetic which became integrated into African design culture? The Nigerian-British artist Yinka Shonibare notes that ‘an image of “African fabric” is not necessarily authentically African’.[ref]1. “African fabrics”: the history of Dutch wax prints (blog) [/ref] Did African design influence European taste? And how did the export of textiles affect the West African textile industry?

Registered by George Kay & Co, 4 March 1908 (catalogue reference: BT 52/60 1227)

The British trade in textiles to West Africa took off from the 1870s onwards, when Britain had become the dominant maritime trading force along what was then known as the Gold Coast. African consumers were discerning, with well-defined tastes. They appreciated innovation, and fashion trends were continually shifting. European merchants worked hard to appeal to their African customers and to anticipate changes in fashion. There was a diversity of styles, with different designs popular in different regions; there was no single ‘African taste’. [ref]2. Alisa LaGamma and Christine Giuntini, ‘The Essential Art of African Textiles: Design Without End’, (New Haven) Yale University Press, 2009[/ref] This is reflected in the range of textiles held at The National Archives.

The company Blakeley & Beving copyrighted a large number of designs. The textile manufacturer Charles Beving, a partner in the company, was listed in the 1891 Manchester census as ‘Africa Merchant’. Although his business was based in Manchester, he spent much of his time trading in Africa, where he carried out research to determine what designs were popular. He built up a substantial trade with West Africa and accumulated a large number of textile samples acquired on his visits. He brought these home to use as inspiration for designs mass-produced in Britain and exported back to West Africa. Beving’s African textiles were given to the British Museum by his son in 1934, where the Charles Beving Collection forms one of the earliest documented and most important collections of 19th and early 20th century African textiles.

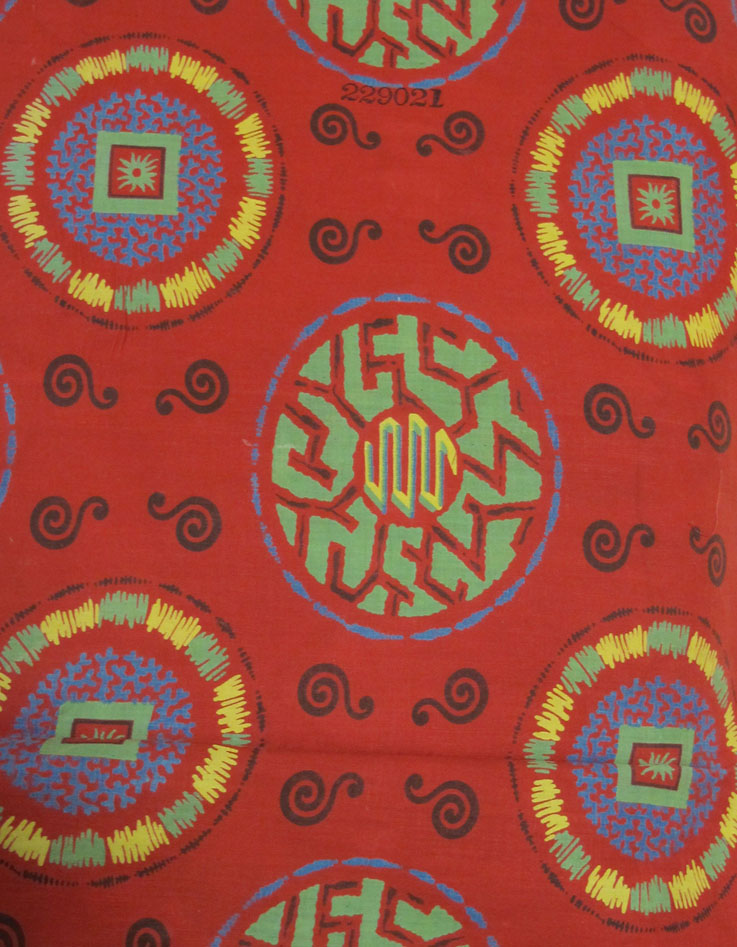

Registered by Blakeley, Beving & Co

(catalogue reference: BT 50-206-229021)

The designs we hold illustrate the way in which the ‘Africa merchants’ drew inspiration from many different African design traditions in order to appeal to their intended markets. These include Asante kente cloths from Ghana; adire indigo resist dyed cloth from Yorubaland, Nigeria (resist dying involves creating a pattern by preventing certain parts of the fabric from absorbing dye); and batiks, originally from Indonesia but also very popular in West Africa.

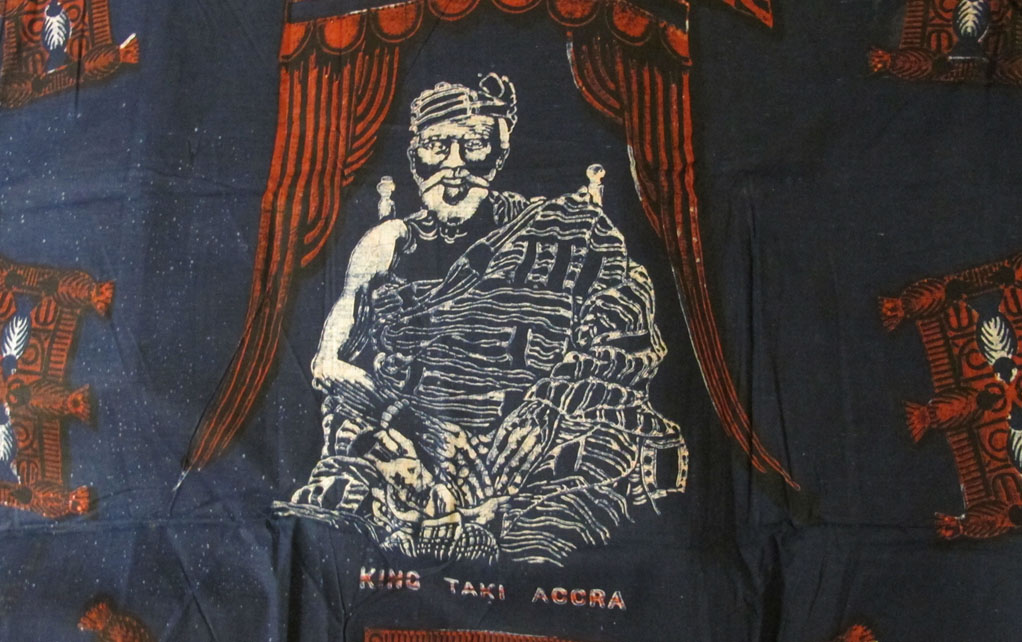

African textiles traditionally use a range of traditional symbols and motifs, as well as depicting historical events, current affairs and political figures. Among the designs we hold are some showing African leaders, such as the one shown here, representing King Taki of Accra. African political leaders have a tradition of commissioning textiles in their own image. It seems very unlikely they would have commissioned work from a European manufacturer, but perhaps King Taki’s power was such that his image would have proved a good selling point.

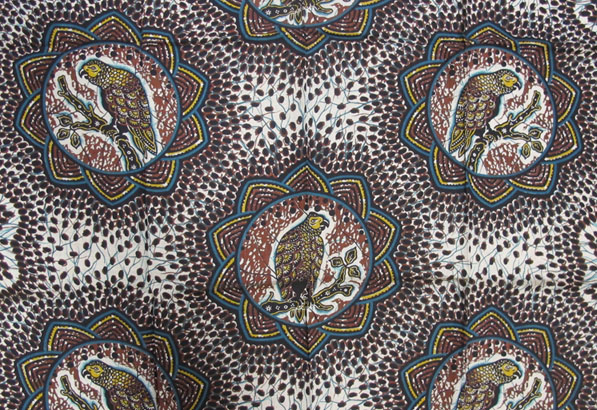

Registered by F W Grafton & Co, 11 March 1908 (catalogue reference: BT 52/60 1362)

There are many examples of textiles in the batik, or wax print, style among the registered designs. They are by companies such as Logan Muckelt, which printed dress fabrics for the African market, Joseph Bridge & Co, also a major player in exporting textiles to West Africa, and F W Ashton & Co, one of the most important printers of imitation batiks. Ashton’s was later subsumed by the Calico Printers Association, which was also well known for printing imitation batiks for the West African market. The invention of the wax print has been referred to as ‘the result of a long historical process of imitation and mimicry’.[ref] 3. Nina Sylvanus, Asia Institute http://international.ucla.edu/asia/article/67940 [/ref] Originally the Dutch were responsible for imitating and industrialising traditional Indonesian batik techniques but Britain, the leader in mass-production of textiles, soon became involved in the trade. When they failed to find a market in Indonesia, the imitation batik textiles were introduced to West Africa, where they became hugely popular.

Registered by the Calico Printer’s Association, 25 September 1918

(catalogue reference: BT 52/3224 152453)

Opinions differ as to the extent to which African textile producers were affected by the European imports. Some argue that the European designs were similar in style to popular indigenous designs, but that the industrially manufactured goods became integrated into an ever-growing market for different varieties of cloth without reducing the popularity of locally-produced cloths. [ref] 4. Alisa LaGamma and Christine Giuntini, ‘The Essential Art of African Textiles: Design Without End’, (New Haven) Yale University Press, 2009[/ref] It’s clear that the British wanted to compete with African cloth industries – some historians refer to ‘cotton imperialism’. It seems that in reality British traders had to be content with existing alongside local industry. In 1907 the Acting Governor of Northern Nigeria, Sir William Wallace, wrote:

‘The native cloth, though less showy than English cloth, is much more durable and better value . . . [no local person] will take the English material if he can possibly get the latter [locally produced cloth]’.

It seems that imported textiles could not compete with locally produced ones, but instead may have found their own place within a thriving market.[ref]5. Johnson, Marion, ‘Cotton Imperialism in West Africa’, ‘African Affairs’, 73, 291:178-187, 1974 [/ref]

Registered by Logan Muckelt & Co, 27 February 1908 (catalogue reference: BT 52/59 1105)

Textiles for sale to West Africa held at The National Archives are an invaluable resource for researchers, including design and textile historians, and shed light on many aspects of the textile trade at this period. They also have potential to provide an inspirational and unique resource for artists and designers in the present day.

Learn more

- Unexpected findings: 100 years of cultural exchange

- A momentous question: decorating the Victorian home (podcast)

- Julie Halls, Inventions that didn’t change the world, Thames & Hudson, 2014

- Questions of attribution: registered designs at The National Archives (article – subscription needed)

This is an informational post on textile designs. I am amazed that the African textile designs are getting immense popularity these days.