Following the success of our ‘Behind the scenes’ repository tours we are currently running tours based on specific themes: this month’s was ‘Crime in the archives’. Here are some of the original documents we selected to show to the tour group…

In the shadow of Newgate

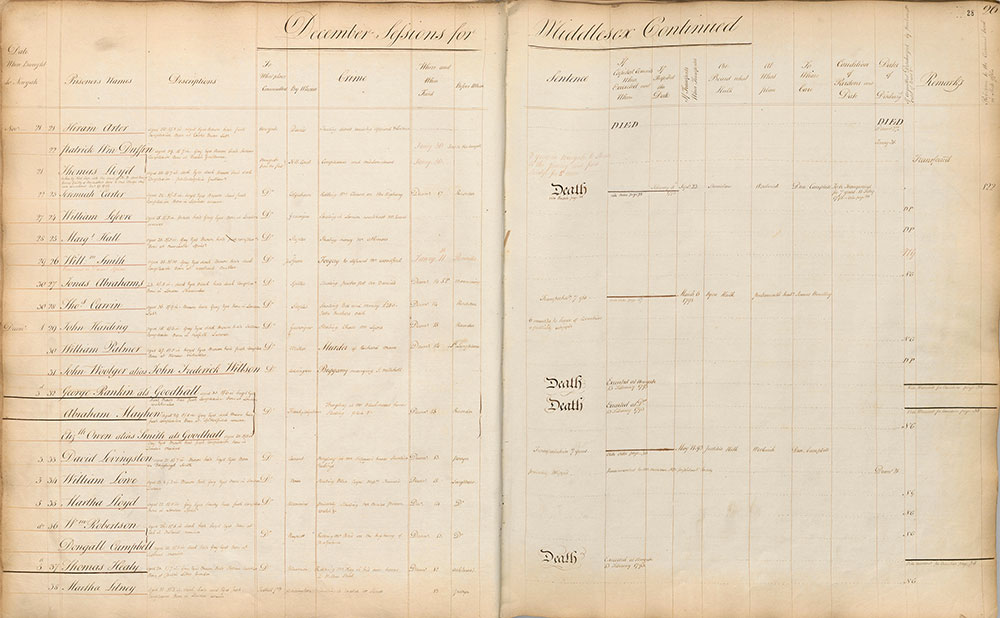

This huge register is made up of lists those held in London’s infamous Newgate prison from 1792 to 1793. Each entry records the name of the prisoner, date of arrival at Newgate, age and a brief physical description, occupation, place of birth, and details of the crime of which they have been accused. The crimes vary widely, with acts of bigamy, murder and cheese theft occupying the same page.

- Newgate register, page showing entries for December 1793 (catalogue reference: HO 26/56)

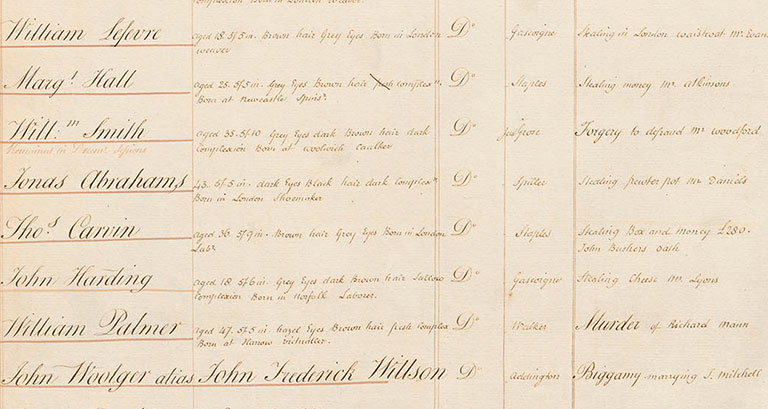

- Close up of the columns listing physical descriptions and crime committed (catalogue reference: HO 26/56)

- The baleful sentence of death appears regularly (catalogue reference: HO 26/56)

The severity of punishments ranges accordingly – from fines and public whippings for minor crimes to transportation or execution for the most serious offenses. While the dramatically-penned sentence of ‘Death’ appears on a regular basis throughout the pages, on the majority of occasions it appears to have been commuted to a custodial sentence or transportation for a set period, with execution appearing to only actually take place in cases of murder, highway robbery or high-value theft.

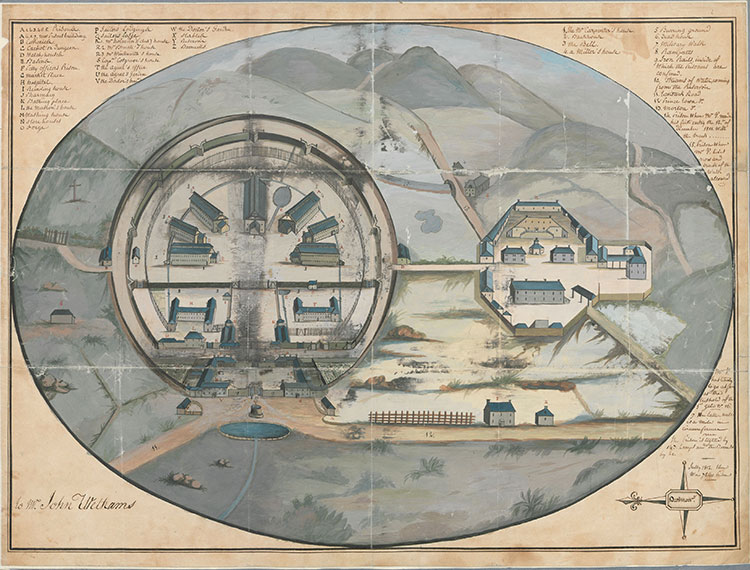

Imprisoned on the Moor

Dartmoor Prison was originally constructed in 1809 during the Napoleanic wars to hold large numbers of French prisoners of war, who were joined shortly afterwards by American prisoners from the War of 1812.

The inland prison was considered a better option than the unsanitary prison hulks that had previously been used for holding prisoners, and the remote location allowed for fewer chances of escape for those held within. At one point, somewhere in the region of 6,000 men were held within its walls – a huge number when you consider that the modern capacity is set at just over 600. When conflict with France and America ceased in 1815, prisoners were gradually released and the prison lay empty until 1850, when it was re-purposed and partially rebuilt as the civilian prison that it remains today.

The Putney Park Lane Murder

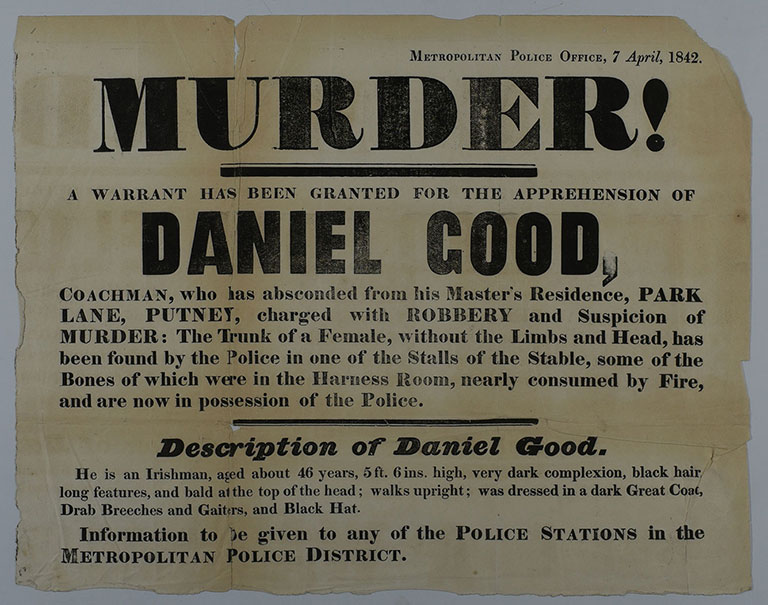

- Wanted poster for murderer Daniel Good (catalogue reference MEPO 3/45)

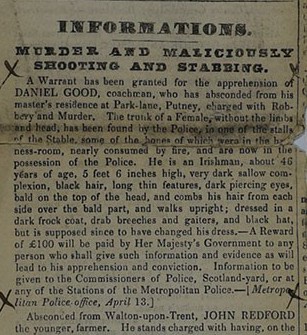

- Article from the Police Gazette reporting the crime (catalogue reference MEPO 3/45)

The circumstances surrounding the this brutal murder are sometimes credited as being the catalyst that led to the creation of an official detective force in England.

After murdering and dismembering Jane Jones (his common-law wife) in April of 1842, Putney coachman Daniel Good foolishly drew police attention to himself by stealing a pair of trousers from a pawnbroker. When a constable was sent to search for the stolen property in the stables where Good was employed, he stumbled upon the dismembered body of Jones; before he could act, Good managed to lock him in the stable and escape. He was on the run for ten days before being recognised by chance and arrested in Kent. The incident caused the police much embarrassment, as they were widely and scathingly reported on by the press. The discovery of the murder, escape of the suspect and his eventual capture all occurred by mistake rather than design and made the force appear incapable at best.

Good was executed at Newgate on 23 May, and shortly afterwards the Metropolitan Police set up the first investigative unit of its kind in England. The Detective Department was rebranded in 1878 as the CID (Criminal Investigation Unit), and still deals with major crimes requiring complex detection.

Murder of the Prime Minister

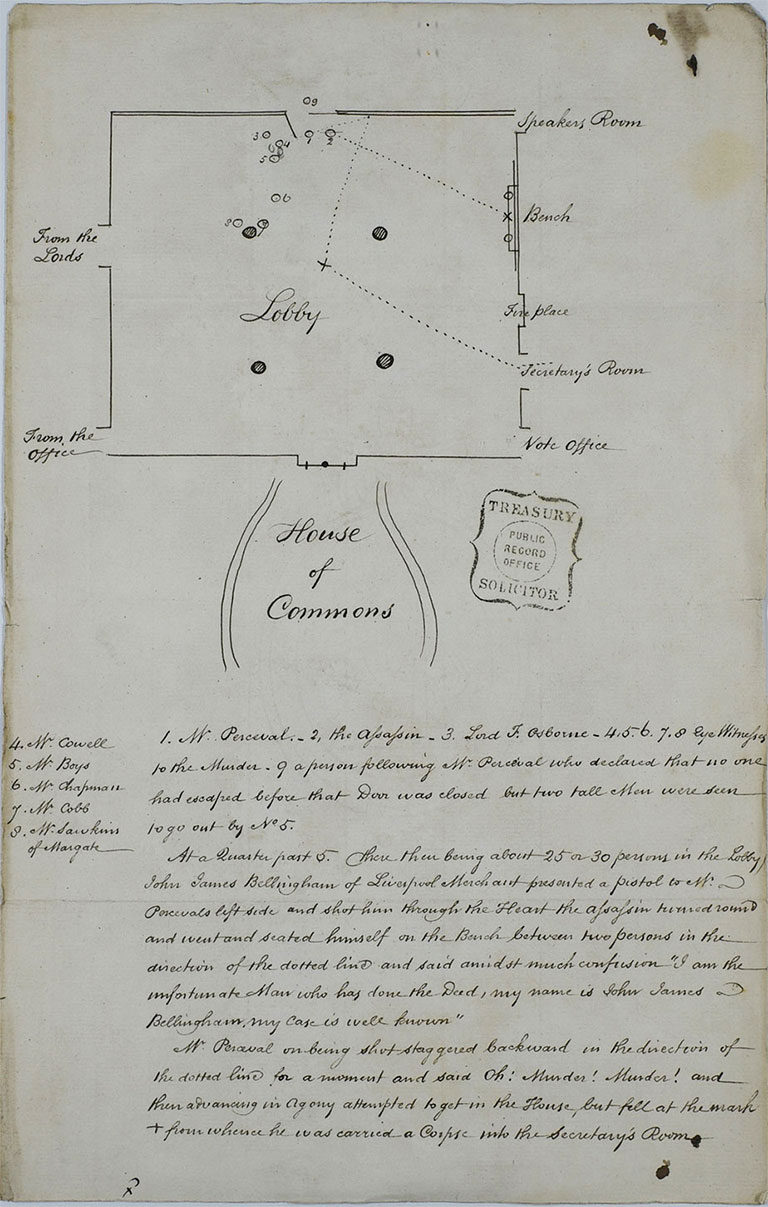

- Illustration of the lobby of the house of commons, with locations of the victim, perpetrator and others (catalogue reference: TS 11/224)

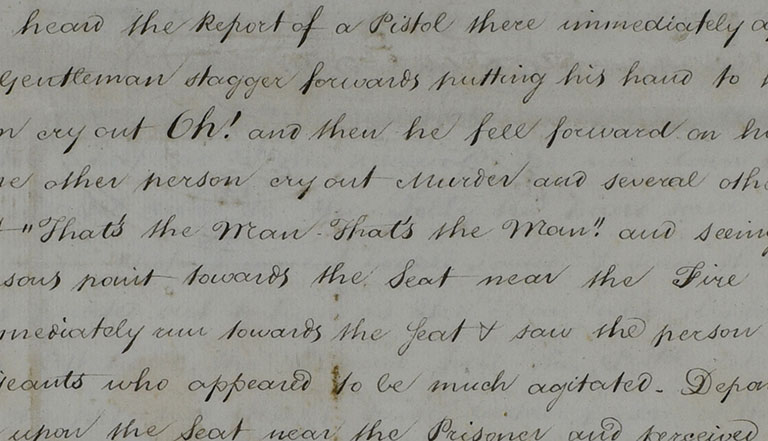

- Part of a witness statement of the assassination (catalogue reference: TS 11/224)

While working in Russia in 1804, export agent John Bellingham became enmeshed in a tricky financial issue which led to him being imprisoned. His repeated attempts to secure assistance from the British government failed, as did his claims for compensation on his release and return to England five years later. Bellingham chose to express his displeasure in the most extreme of ways: in the early evening of 11 May he waited patiently for Prime Minister Spencer Perceval to enter the lobby of the House of Commons, stepped forward and calmly shot him in the chest. Perceval was dead within minutes, the only British Prime Minister ever to be assassinated. Bellingham made no attempt to escape or resist arrest, and at his subsequent trial refused to plead insanity despite the attempts of his defence council, claiming that he was fully justified in his actions.

‘I had no personal or premeditated malice towards that gentleman; the unfortunate lot had fallen upon him as the leading member of that administration which had repeatedly refused me any reparation for the unparalleled injuries I had sustained in Russia.’

The jury took only minutes to find Bellingham guilty. He was hanged at Newgate and his body given over for dissection – a common fate for executed criminals.

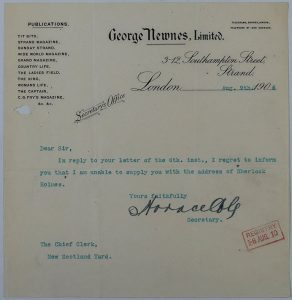

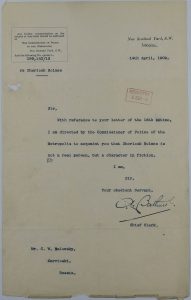

The fictional detective

This file contains numerous letters to Scotland Yard from individuals hoping to make contact with the famous detective Sherlock Holmes – the enquiries hail mostly from European locations including Naples, Moscow, Romania and Vienna. Each was answered with a letter explaining that Holmes was a purely fictional character and would therefore not be able to assist. At the time, Holmes’ fictional address – 221b Baker Street – did not exist. However, this changed after a reallocation of the street numbers in the 1930s and letters to the detective arrived there instead of being forwarded to Scotland Yard. Apparently the Abbey National branch which occupied the address employed a secretary to answer letters addressed to Holmes – and in a softer tone than that employed by Scotland Yard, explaining that Mr Holmes was no longer detecting and had left London to enjoy a rural retirement in Sussex.

- Letter regretting that Sherlock Holmes’ contact details cannot be supplied (catalogue reference: MEPO 2/8449)

- Letter explaining that Sherlock Holmes is a fictional character and not a working detective (catalogue reference: MEPO 2/8449)

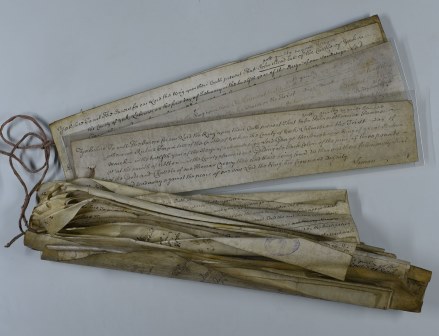

A pardon for pirates

The increasing expansion of colonial trade in the mid to late 17th century led to what is commonly known as the golden age of piracy. The continuous conflict between pirates and the authorities led to the British government issuing periodic amnesties or ‘Acts of Grace’ – such as this one, issued by William III in 1698 – pardoning all pirates (with the exception of certain named individuals) who surrendered to the appointed authorities before the pardon expired. Decrees such as this one were controversial: some believed that, rather than dissuading piracy, they instead provided a ‘get out of jail free’ card, and a way for habitual criminals to periodically absolve their criminal past and avoid serious prosecution.

Portrait of a prisoner

During the early 19th century a huge number of crimes that had previously carried a capital sentence were downgraded to custodial sentences, creating a pressing need for prisons. Constructed in 1842, Pentonville Prison was designed to keep inmates segregated from one another – a far cry from previous prisons where inmates mixed freely. The ‘separate system’ required that each prisoner have their own cell and inmates were forbidden any contact with each other. During group recreation, each inmate even wore a thick cloth mask to prevent any form of communication. Pentonville quickly became the model for British prisons, with the enforced isolation and the use of hard labour highly regarded as a method of forcing convicts to reflect on their own crimes and to encourage reform.

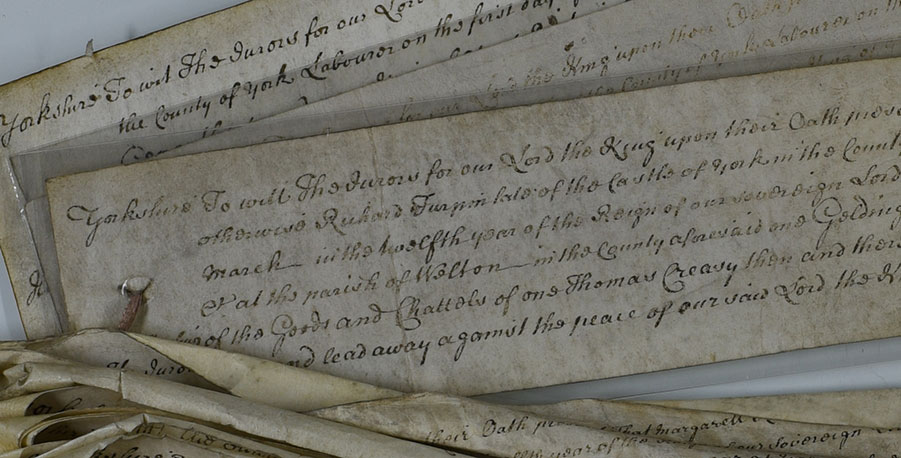

Indictment of Dick Turpin

- Azzises records for the northern and north-eastern circuit, 1739 (catalogue reference: ASSI 44/54)

- Close up of the charge of horse theft against Richard Turpin (catalogue reference: ASSI 44/54)

Born in Essex in 1705, Turpin embarked upon a varied criminal career at a young age. He tried his hand at house-breaking, smuggling and livestock rustling, among other pursuits, before turning his hand to highway robbery. Several years and at least one murder later, while living under the alias John Palmer, Turpin was arrested for stealing a mare worth £3. His true identity was revealed while he was imprisoned and he was tried and convicted for horse theft – at that time a capital crime. He was hanged at York on 7 April 1739, with posthumous and highly dramatised versions of his exploits earning him a permanent place in British folklore.

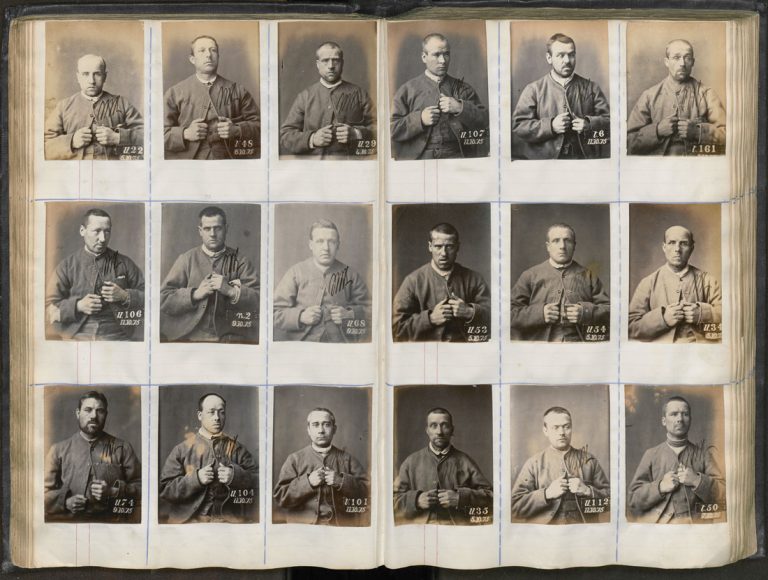

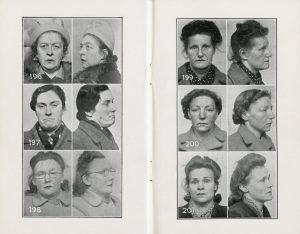

Pocket pics of pickpockets

This booklet of 1951 comes from a series of confidential books and instructions issued for the use of the Metropolitan Police in identifying known criminals. Each offender has been photographed face-on and in profile, and an index at the back of the book gives their names, aliases, common disguises, distinguishing marks and behaviour when apprehended, including violence and feigned drunkenness.

- Mugshots of known pickpockets, 1951 (catalogue reference: MEPO 8/48)

Try one of our Behind the Scenes tours

Book a place on our next Behind the Scenes tour: Richmond in the Archives, on Friday 10 November at 10:00.

Or contact us to arrange a private group tour:

- dsdtour@nationalarchives.gov.uk

- 020 8876 3444 ext 2132

As you probably Dartmoor Prison is to be closed in about three years.

Hi David, I read a lot of articles stating that closure was on the cards but couldn’t find confirmation of when – will be interesting to see what they do with the site if so as I believe several of the buildings are listed.

Hi Eleanor,

This link goes back to 2013 (https://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/sep/04/dartmoor-prison-closure-shakeup-jails), there are other such articles but very recent press articles including one in Plymouth suggest it may be put on ice, due to prison numbers. I expect you know it is leased from the Duchy of Cornwall (Prince Charles) and the 200-year lease was not being renewed, there was a very well-known breakout in the early 1930s , there are files on this at TNA.

Is it possible to book this tour for 18 December? We live in Sydney and will be visiting uk for Christmas and would love to come.

Hi Caroline, if you’d like to e-mail me at dsdtour@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk I can send you some information about group bookings