Shortly before the bombing raid on Coventry in October 1940, the film London Can Take It, in which American journalist Quentin Reynolds paid tribute to the people of London enduring the Blitz, was released in the United States. The aim of the film was to gain American support against Nazi Germany. After the night of 14 November it became apparent that Coventry also ‘could take it’. [ref] 1. HO 199/178 [/ref]

In fact, the city of Coventry was repeatedly bombed throughout the war, largely due to its metalworking industry and munitions factories, which made it one of the prime targets for the Luftwaffe (the German Air Force).

The raid

The raid suffered by Coventry on the night of 14 November was of a scale usually only experienced by Londoners. It began at around 19:20 and continued to approximately 06:15 the following morning. Coventry ‘was continuously attacked by relays of enemy aircraft for some 11 hours’. [ref] 2. HO 202/2 [/ref] It was a bright moonlit night – perfect for raiding.

First page of a report on the air raid on Coventry from the weekly report of the Ministry of Home Security (catalogue reference: HO 202/8)

During the night ‘some 350 aircraft were over the country, 300 of them going to Coventry’; they dropped a torrent of bombs on the city.[ref] 3. HO 202/2 [/ref] The first were incendiary bombs. Some of the initial fires were put out, but soon there were too many for the local fire service to combat and the city was ablaze. These fires acted as beacons for the relays of aircraft that followed.

Early on in the raid telephone communications were knocked out. This, coupled with debris blocking the roads, meant it was difficult for rescue teams and the emergency services to get into the city. At 03:30 it was reported that the ‘attack continues in intensity…[and] hardly any street has avoided some damage’. [ref] 4. HO 199/178 [/ref] By the morning of 15 November around 600 troops had been drafted in to help with clearing roads and diverting traffic around the city. [ref] 5. HO 199/178 [/ref]

The bombs fell ceaselessly all night. Gas and electric supplies were cut off and damage to water mains meant that water had to be pumped from the Sherborne river and canal to combat fires. By 03:00 around 200 fires had been reported. In some places buildings had to be demolished to prevent fires spreading; others were left to burn themselves out. [ref] 6. HO 203/5 [/ref] Despite this, by the following morning most were under control.

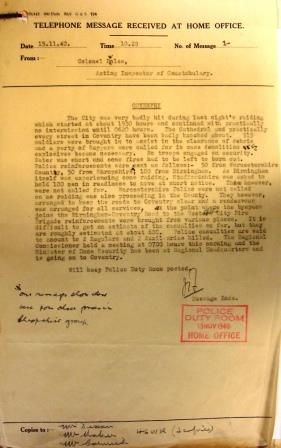

On this single night much of the city centre was destroyed. A telephone message received by the Home Office at 10:29 on the morning of 15 November stated ‘The Cathedral and practically every street in Coventry have been badly knocked out’. [ref] 7. HO 199/178 [/ref]

Telephone message received by the Home Office (catalogue reference: HO 199/178)

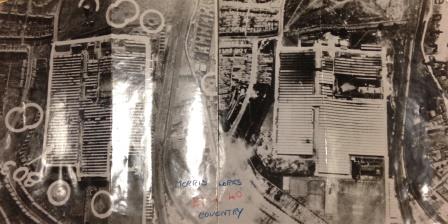

Many factories in the city suffered damage, including Morris Bodies Ltd, a manufacturer of motor parts that had begun manufacturing light guns to aid the war effort. One of the tallest buildings in the city, comprising five storeys, it received two direct hits to the roof from a 250kg and a 50kg bomb. Both bombs penetrated the roof and the floor below, and detonated on the second floor down. Despite this, machines were not seriously damaged and production was not seriously hindered. [ref] 8. HO 199/178 [/ref]

The site of Morris Bodies Ltd and bomb craters around the building, taken just over a week after the raid (catalogue reference: AIR 34/734)

Gallantry recommendations

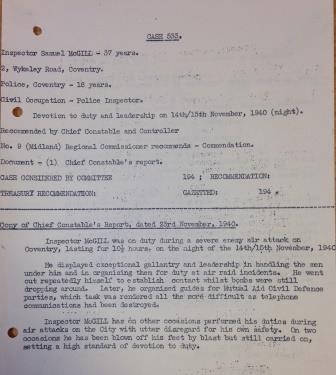

Samuel McGill’s recommendation for a gallantry award (catalogue reference: HO 250/12/533)

Despite the devastating situation the people of Coventry were faced with, morale within the city remained high. The daily police situation report of 15 November 1940 states that ‘throughout this most severe ordeal the public order was excellent and the morale of the people although severely tested, remains exemplary’. [ref] 9. HO 199/178 [/ref]

Some individuals were specifically highlighted for reward, including Inspector Samuel McGill, who displayed exceptional gallantry and leadership by repeatedly going out to establish contact while bombs were still dropping. The recommendation outlined that ‘On two occasions he has been blown off his feet by blast but still carried on, setting a high standard of devotion to duty’. [ref] 10. HO 250/12/533 [/ref]

The series HO 250 has recently been digitised and is available via Ancestry. See Rebecca Simpson’s recent blog post on Second World War home front heroes for more information.

As a result of the raid there were significant casualties: 508 people were killed, 877 seriously wounded and 373 slightly wounded. In a report dated 19 December 1940 by R A Youll, he stated, ‘there is no doubt whatever that the citizens of Coventry stood up to this appalling raid with admirable fortitude’.[ref] 11. HO 199/178 [/ref]

Cathedral destroyed

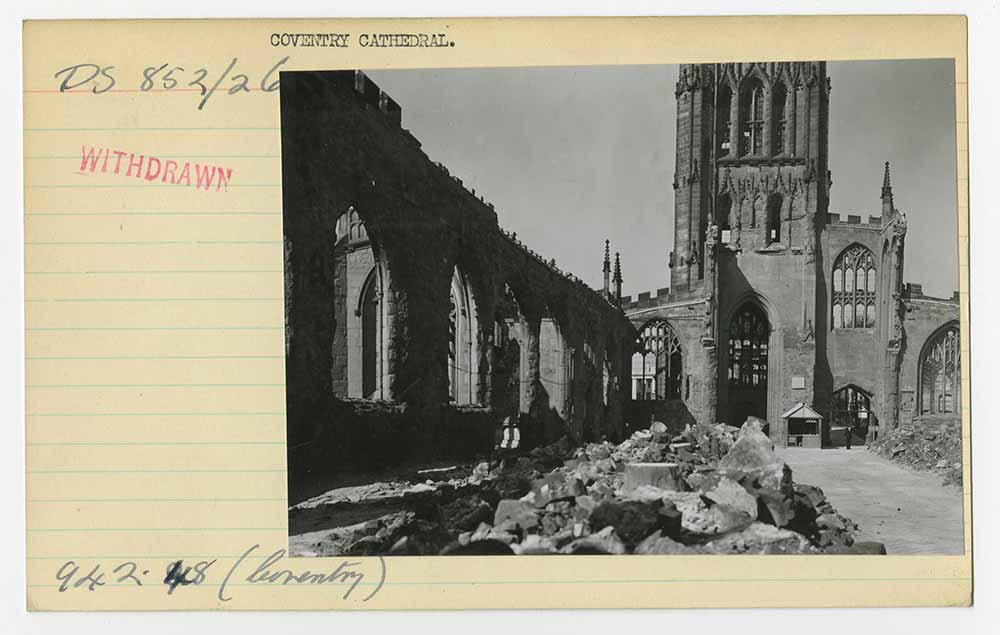

Coventry Cathedral was among one of the areas most devastated by the raid. It was hit early on in the raid by incendiary bombs. The first fires were put out, but subsequent hits could not be controlled and took hold of the cathedral. The only parts of the building to survive were the spire, tower and outer wall, which can still be seen today.

Coventry Cathedral (catalogue reference: INF 9/733/26)

Aftermath

By daybreak police reserves had also been sent to Coventry with blankets and rations to support the city.[ref] 12. HO 199/178 [/ref] Field kitchens were set up to provide hot food for the homeless and destitute while the gas and electricity supplies were restored.

The city was relatively quick to recover. By 16 November water was available at low pressure and electricity had almost been restored to normal but the gas supply remained limited.[ref] 13. HO 199/178 [/ref] Businesses sought to get up and running quickly and by 18 November some factories had started work again.[ref] 14. HO 199/178 [/ref] On the same day a full letter and parcel delivery service was running, delivering 10,000 telegrams on that day alone.

Report by Lieutenant John Miller on neutralising unexploded bombs (catalogue reference HO 199/178)

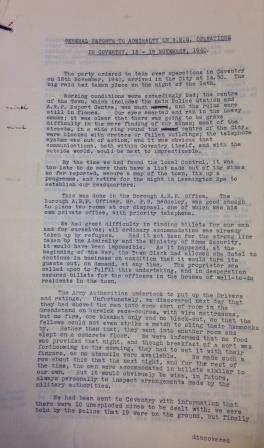

Unexploded bombs and mines posed the main threat. There were around 300 unexploded bombs and 17 unexploded mines which had to be defused. [ref] 15. HO 199/178 [/ref] In a report to the Admiralty dated 20 November 1940 Lieutenant John Miller RNVR, the officer in charge of the operation to neutralise the mines, recalled ‘working conditions were exceedingly bad… Our eyes smarted and ran in the heavy smoke; it was clear that there was going to be grave difficulty in the mere finding of our mines’.[ref] 16. HO 199/178 [/ref] He also commented, ‘we were very much struck by the behaviour of the civil population in the City…the people behaved with perfect coolness and order, which was a great help to those who were trying to assist them’.[ref] 17. HO 199/178 [/ref]

Every aspect of city life was affected. Of 66,000 houses, 37,247 suffered some form of damage; 20,000 were uninhabitable and of these 2,500 completely wrecked and had to be demolished. Similarly, of 180 principal factories 130 were more or less seriously damaged and nearly all roads within a mile of the city centre were impassable.

A royal visit

On Saturday 16 November King George made a visit to Coventry to see the damage of the raid first hand. The visiting inspectors’ report states:

‘the King’s visit to Coventry on the Saturday made an astonishing difference to morale. Observers stated that a spirit of civic pride – pride in the work of the A.R.P. Services and in the resilience of the city as a whole – had begun to make itself felt.’[ref] 18. HO 199/178 [/ref]

Restoration of the city

From this destruction arose a new city. Factories that were damaged during the raid were quickly repaired or rebuilt.

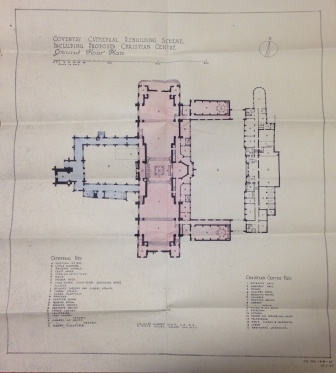

After the war, in 1950, a competition was launched to find an architect to design a new cathedral. Basil Spence won the competition and the foundation stone of his new design was laid in 1962. Rather than demolish the remains of the old cathedral, the new cathedral was built alongside its ruins, which remain as a garden of remembrance.

Plan for the new cathedral by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, before the competition was launched (catalogue reference: IR 36/49)

The Government had planned to put Coventry under Martial Law after the raid (see “The World at War”) but the city decided that this should be a civil issue and they won the argument. The question over whether the bombing of Coventry was known about in advance (see Professor R V Jones), it was found that it was to be in the Midlands. The bombing lead to the creation of a National Fire Service as the fire hoses used outside Coventry were not compatible (see “The World at War”).

[…] Shortly before the bombing raid on Coventry in October 1940, the film London Can Take It, in which American journalist Quentin Reynolds paid tribute to the people of London enduring… Go to Source […]

What lovely images and how well referenced! Thank you Dr. Down for your very thorough work. I love visiting the TNA for its maps, and always get the most competent help! Thank you very much!

Your Blog is very interesting & informative to read.

Thanks for writing:)

I believe there are two inaccuracies in this article. The first is that the Morris Bodies factory was 5 storeys in height. This is incorrect. I think the reference must be to the Morris Engines factory in Gosford Street, which indeed was this height. The second is that the note to the aerial photo says “Morris Bodies”. This is incorrect as the photo is of the Morris Engines works at Courthouse Green. The Morris Bodies factory at Quinton Road was much smaller.