From 5-9 November 1914, Rear-Admiral Ernest Charles Troubridge stood trial for: ‘from negligence or through other default, forbear to pursue the chase of His Imperial German Majesty’s ship ‘Goeben’, being an enemy then flying’ (ADM 156/76). The case against Troubridge, outlined in various documents held here, reveals the difficult and demanding nature of command during a time of conflict, and especially the delicate problem of interpreting orders.

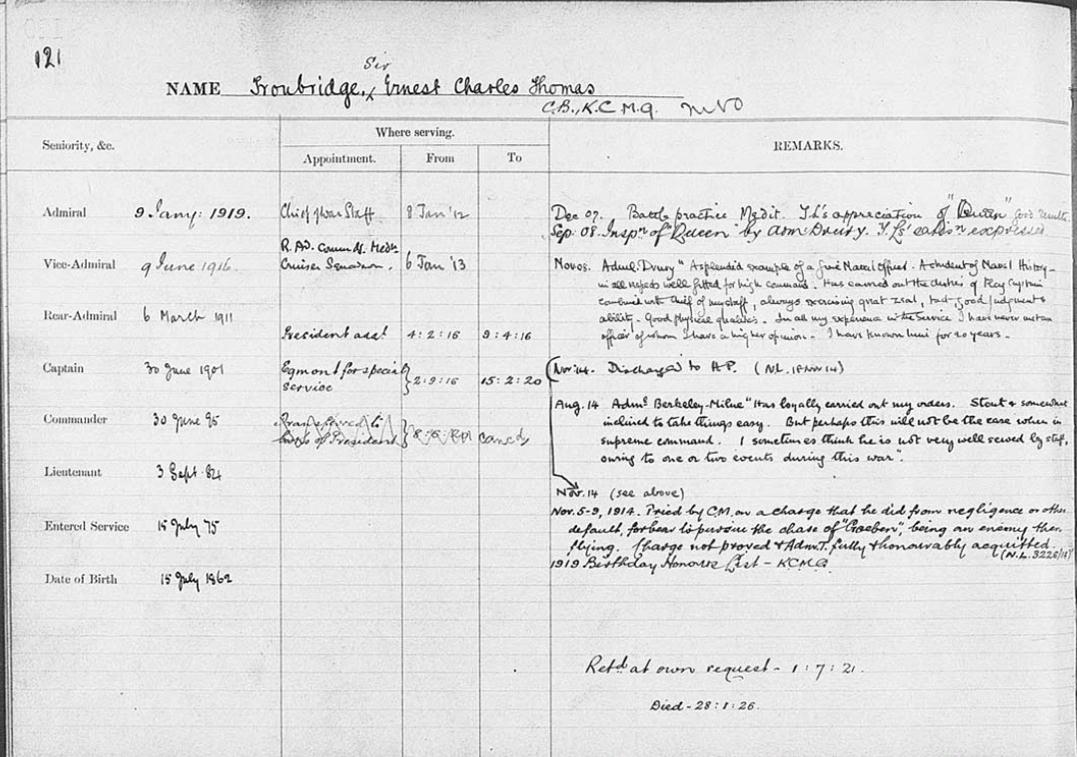

The service record of Rear-Admiral Troubridge, available to view online, reveals an experienced naval officer. Born in 1862, Troubridge first entered the Navy in 1875 and became a Lieutenant in September 1884. Promotions to Commander (1895), Captain (1901), and Rear-Admiral (1911) followed and prior to the outbreak of war in August 1914, Troubridge’s record is full of positive remarks from superior officers regarding his ability, tact and judgement as a naval officer (ADM 196/87/120).

Service record of Ernest Troubridge, revealing a long naval history and many positive remarks from superior officers regarding his ability (Catalogue reference: ADM 196/87/120)

The last remark on his service record prior to the First World War came from Admiral Drury in November 1908. Drury states that Troubridge was a ‘splendid example of a fine Naval officer’, that he was ‘well fitted for high command’, and had always ‘shown great zeal, tact, good judgement and ability’. Drury closed with his belief that he had ‘never met an officer of whom I have a higher opinion’ (ADM 196/87/120).

At the start of August 1914, Troubridge was commanding the First Cruiser Squadron of the Mediterranean Station. Troubridge reported to the Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean, Admiral Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne. On Troubridge’s service record, interestingly dated August 1914, Milne states that Troubridge had ‘loyally carried out my orders’, although he was critical of the staff supporting Troubridge at this time (ADM 196/87/120).

The service record also states that between 5-9 November 1914, Troubridge faced a court martial for giving up the chase of the German ship, Goeben. Working into the collection of Admiralty courts martial cases and files in ADM 156, you can find the Troubridge proceedings of November 1914 simply by searching our online catalogue, Discovery, by his surname. In other cases, you may need to use the ADM 12 Indexes and Digests.

Having been in charge of the First Cruiser Squadron, Troubridge was in pursuit of the German battle-cruiser Goeben during 6-7 August 1914. The First Cruiser Squadron consisted of HMS Defence, Warrior, Duke of Edinburgh and Black Prince, and was positioned at the entrance to the Adriatic Sea on the 6 August, where they believed the Goeben was heading. HMS Gloucester was following the Goeben when she changed course and headed south, away from the Adriatic towards the Eastern Mediterranean at 22:46 on 6 August. Troubridge turned the First Cruiser Squadron south at midnight, intending to cut off the Goeben by 06:00 on 7 August. At 04:00, Troubridge called off the chase, despite also having HMS Dublin, Beagle and Bulldog under his command. Troubridge told Milne that this was due to only being able ‘to meet with Goeben outside the range of our guns and inside his’ (ADM 156/76).

Professional and political criticism of Troubridge followed. A Court of Inquiry was held on 22 September 1914 at Portsmouth, with a copy of the minutes to be found within the court martial case file within ADM 156/76. As a result of the inquiry, Troubridge was charged under section three of the Naval Discipline Act (ADM 156/76).

The court martial took place aboard HMS Bulwark and the minutes of this trial reveal the difficulty of command during a period of conflict, especially how the interpretation of orders passed down through the chain of command can lead to differences of opinion or understanding.

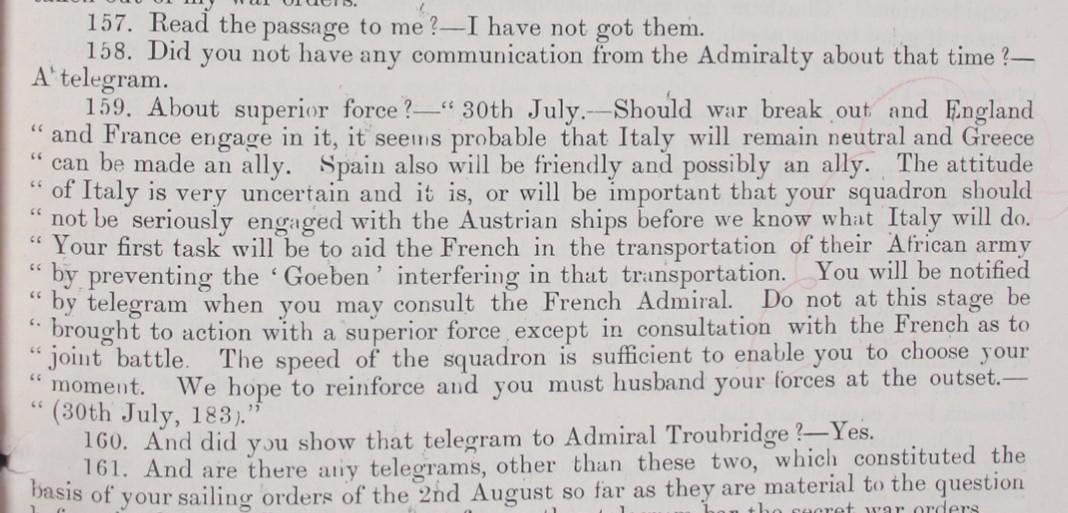

Orders from Admiralty to Admiral Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne, 30 July 1914, regarding situation in the Mediterranean. Taken from minutes of court martial proceedings. (Catalogue reference: ADM 156/76)

The minutes reveal that on the 30 July, 1914, Milne was advised by the Admiralty in London that:

‘Your first task will be to aid the French in the transportation of their African army by preventing the “Goeben” (a German battle cruiser) interfering in that transportation’ (ADM 156/76).

The assessment continued:

‘Do not at this stage be brought into action with a superior force except in consultation with the French as to joint battle. The speed of your squadron is sufficient to enable you to choose your moment. We hope to reinforce and you must husband your forces at the outset’ (ADM 156/76).

These instructions were passed from Milne to Troubridge. The First Cruiser Squadron was tasked with keeping watch over the movements of the Austrian fleet in the Adriatic, protecting the French ships transporting the French Army back from North Africa to Marseilles, shadowing the German ships Goeben and Breslau, while avoiding superior enemy forces until reinforcements were available.

During his own defence, given on 9 November, Troubridge was keen to make two key points. Firstly, that the Goeben was between three and a half and seven knots quicker than the four British cruisers in pursuit. Secondly, the Goeben had a larger effective range of fire than the British ships. It was for these two reasons that Troubridge considered the Goeben a superior force despite being only a single ship, and thus reverted back to the instructions passed from the Admiralty to Milne on 30 July (ADM 156/76).

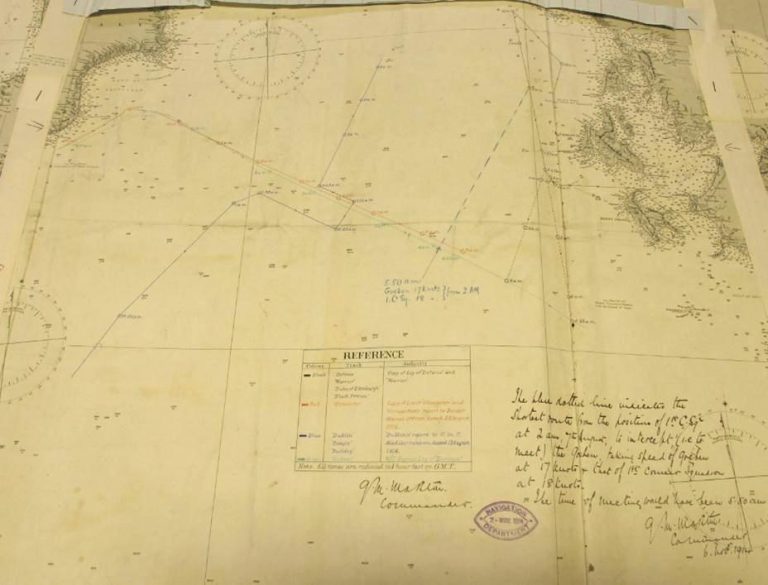

Also available for consultation at The National Archives are two exhibits from the court martial proceedings. These are maps and charts showing the route of the Goeben, the British ships in pursuit, and the movements of the First Cruiser Squadron. The charts also include dotted lines indicating the points and times at which the Goeben could have potentially been intercepted by Troubridge if he had continued the chase or had changed course at different moments (ADM 137/901/1 and ADM 137/901/2).

Exhibit 8 in Court Martial of Rear Admiral Troubridge. First Cruiser Squadron positions are shown to the top right, with dotted lines indicating possible points at which the Goeben could have been engaged (Catalogue reference: ADM 137/901/1)

The minutes of the hearing obviously contain far more detail, evidence and opinions then can be covered in today’s blog post. In fact, the events of early August 1914 continued to have professional and political ramifications, evident in another file – ADM 156/110 – of Parliamentary Questions from 1919, and a sworn oath of Captain Fawcet Wray, Troubridge’s Flag-Captain. Wray’s statement indicates the detrimental impact on his career that the episode had had, the stigma of being silently labelled a coward within the Navy, and also arguing against the accuracy of the evidence given by Troubridge during the court martial proceedings.

The court, however, found that while the Goeben could have been engaged at alternative locations by Troubridge’s force they felt ‘in view of the accused’s orders to keep a close watch on the Adriatic, he was justified in abandoning the chase at the time he did’. Likewise, the court also declared that Troubridge was right to consider the Goeben a superior force based on ‘the particular circumstances of weather, time, and position’ of the relevant ships and the likely place at which they would have met. The court honourably acquitted Troubridge of the charge against him, returned his sword and dissolved the court (ADM 156/76).

Despite being cleared of the charges against him, Troubridge was discharged to the Half Pay list. Although appointed to liaison role with the Crown Prince of Serbia between 1916 and 1919, Troubridge never took another appointment commanding a sea-going unit. He retired in 1921 and died in January 1926 (ADM 196/87/120).

When all of these documents are pieced together, while some will interpret them in favour of Troubridge’s decisions and others against. What does become clear is the difficult nature of command during conflict. Perhaps the case of Rear-Admiral Ernest Charles Thomas Troubridge highlights the fine line by which those in command carried out their duties. One deemed bad decision could result in significant loss of life, and effectively end a career in the process. I, for one, cannot begin to imagine the pressure that all ranks, across all arms felt during this conflict.

Troubridge was correct in his decision not to engage Goeben.

The belt armour of the Goeben was 11.0 inch thick. The main guns of the four cruisers in his squadron were 9.2 inch caliber weapons. These guns were not capable of penetrating the Goben’s belt armour. Had Troubridge engaged, only superficial damage could be inflicted on Goeben’s superstructure.

In comparison, the belt armour of his four cruisers was only 6 inches thick. Goeben’s 11 inch main guns would easily penetrate 6 inch of armour belt. The British ships would have been blown to pieces by this heavy caliber gunfire.

Add to this disparity, the fact that the Germans had a 2½ knot speed advantage over his four ships that would allow the Germans to dictate the course of the engagement.

Had Troubridge engaged, the result would have been a greater disaster to the British than was their later defeat at the battle of Coronel, where another British cruiser squadron was annihilated.

The consequences of Goeben/Breslau reaching port (Turkey) should have over-rode the concerns of Troubridge. At that critical point-in-time he, Troubridge) was aware of the stakes involved with successful port entry by Goeben and consort. Those 4-Armored Cruisers (Defense, Black Prince, Duke of Edinburgh, Warrior) were the top of their class and, supported by several destroyers, were certainly capable of severely damaging , possibly sinking Goeben with correct deployment/attack plan. The weight of firepower, number of big guns, number of ships and all attacking at once would have favored Troubridge, not Goeben. The River Plate sea battle of WW2 is an excellent analogy of a confrontation outcome between the four-armored cruisers plus destroyer support against Goeben and light cruiser Breslau. Too many late model armored cruisers, closing fast, for the battle cruiser to pick off one by one. Torpedo capability by every British ship present, especially the small fast British Desroyers. There was too much riding here for a British Admiral not to risk an attack. The great British Admiral Nelson would not have hesitated! History has shown the awful consequences of Goeben/Breslau making port in Turkey.

David Abney

Was it a conspiracy to bring the Ottoman Empire into the war, defeat it and seize the oil reserves?