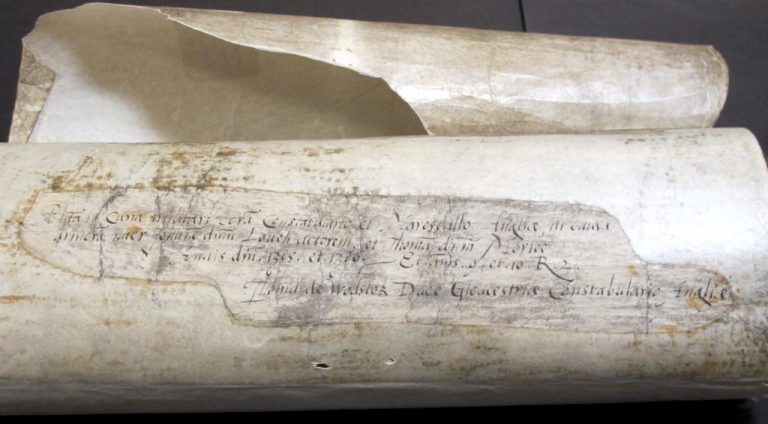

Records of proceedings in the Court of Chivalry for the legal dispute between John Lord Lovell and Thomas Lord Morley over the right to bear heraldic arms of a black lion, rampant with a golden crown, on a silver field, 1385-86 (catalogue reference: C 47/6/1).

“The highest and most sovereign things a knight ought to guard in defence of his estate are his troth and his arms.”

These were the words of Richard Lord Scrope of Bolton proclaimed to Sir Robert Grosvenor in the presence of the king at the Palace of Westminster on 11 November 1391, recorded verbatim in the Calendar of the Close Rolls.

Sir Richard Lord Scrope had recently won the right to bear a certain shield of arms against Sir Robert Grosvenor (C 47/6/2), a Cheshire knight, after a four year dispute in the Court of Chivalry (1386-1390) and was now demanding his defeated rival pay recompense for damages and costs. The suit had been filed in the court in 1386 after it had become apparent during Richard II’s Scottish campaign the previous year that both parties had displayed similar arms: a gold bend (a thick strip running diagonally across the shield) against an azure (blue) background. It is likely that the duplication was accidental.

Armorial seal of Sir Richard Lord Scrope of Bolton, dated 1399. The armorial shield here is elaborately stylised with a pattern of foliage on either side of a crosshatched bend. The livery colours would have been the same as the shield of arms in the dispute with Sir Robert Grosvenor: an azure background with a gold bend. (catalogue reference: E 42/4).

Such heraldic disputes were frequent in the fourteenth century due to a rise in military activity and chivalric ideals triggered by the Hundred Years War. They were hotly contested because arms were principal symbols of profound chivalric honour and identity for a noble family. In many cases the same arms had been used by several generations of the same aristocratic house.

The Court of Chivalry was established in the fourteenth century as an institutional extension of powers already exercised by the constable and marshal of English armies in war. Its creation was necessitated by the increase in armorial disputes and other criminal or legal matters that arose during active military service but were not covered under the umbrella of Common Law, such as disagreements over ransoms for prisoners or evident breaches of the code of knighthood. Copies of proceedings for a select number of law suits heard in the Court of Chivalry, written in French, the language favoured by Chancery clerks, form a small series in Chancery (C 47/6) held at The National Archives. The original rolls of the court are located at the College of Arms in London.

The series is an insightful resource for understanding the growth in litigation and legal issues that arose out of war. It also harbours a hidden treasure trove of biographical details of military service by serving fourteenth century soldiers. Such information is found in several hundred depositions (sworn testimonies) of combatants given during two surviving late fourteenth century disputes over the right to display heraldic arms.

The second case was between John Lord Lovell and Thomas Lord Morley (C 47/6/1) in 1385-6 over the right to bear the arms of silver with a rampant lion, crowned and enamoured with gold. Like the Scrope and Grosvenor dispute, this suit was brought into the Court of Chivalry to be settled as a result of both soldiers bearing the same arms during the Scottish expedition of 1385. Lovell claimed arms by descent to the Burnell family, who had been embroiled in a similar dispute with Thomas Lord Morley’s grandfather Robert over use of the said arms at the Siege of Calais (1346-7). Judgement eventually went in Morley’s favour because of the greater strength of his argument. Through evidence provided by deponents who supported him, he was able to demonstrate continual use of the arms over several generations of his family. His success in the case may also have been influenced by the outcome of the earlier suit brought against Thomas’ grandfather by the Burnell family, which was also won by the Morleys.

Non armorial seal of Robert Lord Morley, grandfather of Thomas Lord Morley, depicting the disputed arms of a crowned lion rampant on the shield. Dated 1334. (catalogue reference: E 42/247).

Soldiers made up most of the deponents in both legal suits because military campaigns were a principal place where heraldic arms would have been exhibited and widely seen by fellow combatants. Deponents tended to be either geographically or militarily affiliated to the litigant they were supporting in some way. The majority of deponents supporting Sir Robert Grosvenor, for instance, were from the same county of Cheshire, whilst the Duke of Lancaster provided testimony in support of Lord Scrope along with many soldiers affiliated with him. However trials were not reduced to partisan slogging matches won by the volume and prestige of witnesses – though both were influential. A soldiers’ testimony was expected to be honest and unembellished and thus reliable.

Each entry in the roll records the deponent’s name, rank and sometimes age followed by how long the deponent has been “armed” i.e. actively serving. The deposition would then contain places, campaigns or battles where the deponent had witnessed the bearing of the said arms and who by. This is therefore evidence of partial rather than complete military service. In a few cases we find clerical and some lay depositions providing non-military evidence in support of one of the litigants of possession of the said arms.

The depositions provided in the Lovell vs Morley dispute divulge several examples of distinguished careers in arms achieved by relatively unknown combatants of England’s many fourteenth century wars. William de Tweyeth for instance, an esquire of 69 years, was a hardened veteran of several fourteenth century campaigns and battles in Scotland and France. His deposition reveals that he was present in Edward III’s Scottish campaign of 1333, both at the siege of Berwick and the battle of Halidon Hill. Seven years later Tweyeth fought at the naval battle of Sluys (1340) where an English fleet defeated a larger French flotilla anchored off the Flemish port of Sluys, successfully curbing French naval power in the Channel. Most notably, he testified to serving with Sir Thomas de Hereford in Edward III’s victorious army at Crecy in 1346.

Depiction of the Battle of Crecy, 26 August 1346 in Chronicles of Jean Froissart (Source: Wikicommons)

The squire not only testified to witnessing the arms of Robert Lord Morley on the battlefield but also on the tournament field, at Dartford in 1331 and Dunstable (1334 or 1342) where he may have either been competing or serving as squire to a knight or nobleman.

Besides deponents like Tweyeth testifying to service with members of the Plantagenet dynasty in France, Scotland and Iberia, others give evidence of military service as hired mercenaries or devoted crusaders. Take Sir Alexander Goldingham who was a deponent in the Scrope vs Grosvenor case supporting Richard Scrope. In his deposition he witnessed the arms displayed by Sir William Scrope at the siege of ‘Nove’ (Novi Ligure, Piedmont, Italy). The town was captured in 1353 by forces of the Duke of Milan and Goldingham was most likely serving with foreign mercenary companies (condottierri) hired by the Milanese dukes. Such mercenaries were widely sought after amongst the patchwork of violent and competitive city states and territories in Italy during the mid and late fourteenth century. It is a largely unknown theatre of English military service during this period.

The rolls of the court depositions also contain more famous individuals such as the writer Geoffrey Chaucer, who was an esquire at the time, of “40 and more” years and confirmed he had been armed for 27 years. Chaucer like Goldingham was also giving deposition in support of Sir Richard Scrope. He testified that on the Rheims campaign of 1359, which was his first experience of combat, at the town of Retters (Réthel, near Rheims) in France he witnessed both Richard and his cousin Sir Henry Scrope bearing the said arms. Chaucer must have been with the forces besieging the town under the direction of the Black Prince. He was unfortunate that upon his first military expedition he was captured by French forces as he confirms in his deposition: “the said Sir Richard armed in the entire arms and [was] so [armed] during the whole expedition until the said Geoffrey was taken.”

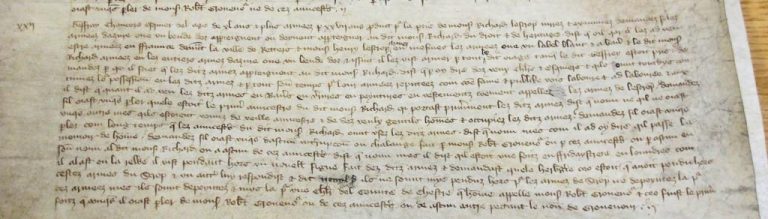

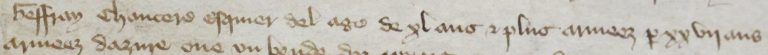

Deposition of Geoffrey Chaucer in the Scrope vs. Grosvenor case in the Court of Chivalry (catalogue reference: C 47/6/2 m.33)

Extract shows Geoffrey Chaucer is an esquire of the age of over 40 years and armed for 27 years. (catalogue reference: C 47/6/2 m.33).

Perhaps the most remarkable information these records reveal is evidence that soldiers could live well into their 90’s in the late Middle Ages after a full and active military career as the deposition of William de Wollaston indicates! He is one of 52 deponents supporting Lord Lovell that survive in PRO 30/26/69 and his record states he is more than 96 years of age. By his own testimony he says that he was first armed at the English defeat at Bannockburn, 72 years before, in 1314!

Admittedly, unlike the more recent records of military service, the picture of service revealed in the testimonies of soldiers in records of the Court of Chivalry is only partial. Deponents were not asked to provide a full exposition of their careers in arms. However given that evidence of military service, where it survives, for the medieval soldier, is rather fragmentary, these testimonies of service provide perhaps the closest medieval approximation to the more comprehensive records of modern military service. These sources give a voice to the military service and deeds performed by members of the knight and sub-knightly classes that are left largely unrecorded in the literary sources of the period. They are an invaluable window to the flourishing military careers of fourteenth century combatants many of whom would otherwise have been forgotten and lost to history.

I think you’ll find he won the right to ‘bear’ arms.

Hi Maureen,

Thanks for spotting this. I have corrected it.

Best regards,

Liz.

These records are very interesting but don’t forget the administrative records too for what they can show about military service (see http://www.medievalsoldier.org)

Dear Professor Curry,

Thank you for reading the blog and for pointing readers to the invaluable Medieval Soldier Database which indeed complements the depositions in the armorial cases in the Court of Chivalry using transcribed original records largely from our collections.

For those readers unfamiliar with the database it is based on original records of army and garrison muster rolls and letters of protection and attorney that have been collated and transcribed and name searchable. The database provides another window onto military service and careers of late medieval soldiers serving between 1369 and 1453.

Kind regards

Benjamin Trowbridge

Another aspect to the ‘Scrope vs. Grosvenor’ trial is a third victim/participant who had the same arms of ‘azure a bend or,” Thomas Carminowe, of Cornwall, who had be charged by the Richard Grosvenor’s wife Margaret and her father no an outcome that is unknown. This happened during Edward III last French campaign. Also in France at this sometime, Carminowe met Scope with a challenge concerning his like arms. Six knights ruled on the challenge said to have happened in 1360. Carminowe stated his family had used the blazon since the days of King Arthur, and Scope stated his family used the blazon since the days of William the Conqueror. The final rule was by ‘The Black Prince’ who’s opinion was that since Carminowe was from a different country he was entitled to use the blazon.

Dear Mr Bryant,

Many thanks for reading the blog and your informative comment.

This is something is was not aware of which provides and extra twist to the Scrope vs. Grosvenor case. Do local records or private papers shed light on this incident?

Kind regards.

Benjamin Trowbridge

The King Arthur claim is interesting, as is Cornwall (Kernow) a different country. Looking at King Arthur tapestry as one of the nine worthies he is bearing the three crowns. I wonder if there are any records of these arms. .