The office of coroner was formalised in 1194. Their main responsibility was to consider the circumstances of sudden or violent death in order to establish the identity of the deceased and the cause of death.

In cases of violent death, and therefore suspected murder, the coroner was empowered to appoint a jury to hear any witnesses and evidence and record a verdict as to cause of death. A coroner’s inquest could therefore lead on to an indictment in a superior court.

The earliest coroners’ rolls and files in The National Archives are to be found in series JUST 2, from the 13th to 15th century. Later inquests are attached to the indictment files in the King’s Bench records. There are also other jurisdictions: the palatinates of Chester and Lancaster, the Duchy of Lancaster, and the High Court of Admiralty.

From 1487, coroners presented their inquests to the judges at the assizes; those not resulting in a trial for murder or manslaughter were forwarded to the King’s Bench. Those filed from 1485 to 1675 are in the series KB 9; those from 1675 for the city of London and Middlesex in KB 10; and those for other counties in KB 11. The filing of inquests with the indictment files stopped in 1733, and the handing in of inquests by 1750, except for the Western circuit where inquests survive to 1820 in the series KB 13. Some inquests and related material may survive within Assize records. An example is the inquest on Amy Robsart, wife of Lord Robert Dudley, which can be found filed in KB 9 under Michaelmas 1562.

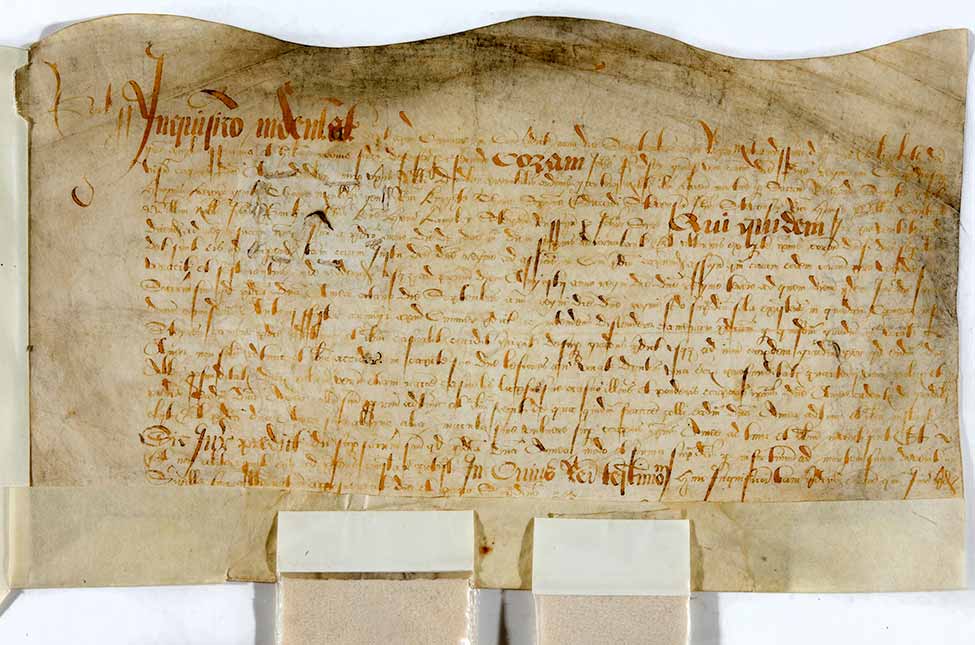

Coroner’s report on the death of Amy Robsart, 4 Eliz I Mich (catalogue reference: KB 9/1073 m.80)

Where a pardon was granted, the inquest may be attached or replicated in the pardon itself. This is the case of the inquest (1 June 1593) into the death of Christopher Marlow (30 May) and the subsequent pardon of Ingram Frizer, discovered by the American scholar J Leslie Hotson in the Chancery Recorda files in 1924. The pardon was also enrolled on the Patent Rolls (28 June 1593). Hotson transcribed, translated and published the document in 1925.

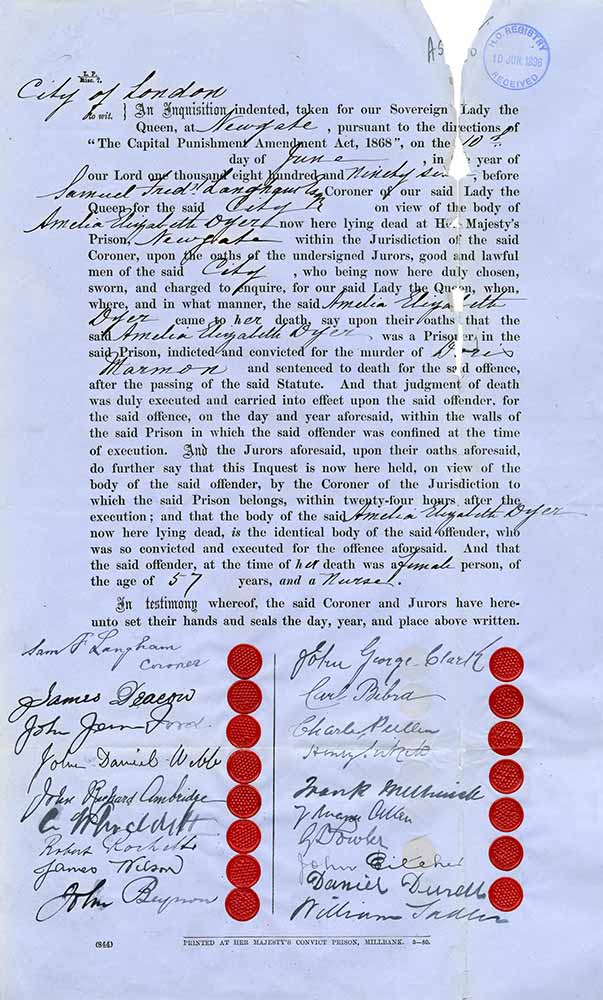

It is possible to find some coroners’ records in The National Archives relating to criminal trials after the early 18th century. Copies of inquests and related material such as witness’ statements and newspaper reports can be found in the case files of the Home Office (HO), Metropolitan Police (MEPO), Central Criminal Court (CRIM), Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) and the Assizes (ASSI). Inquests could be held on convicts dying in prison, or inmates dying in the workhouse, and even felons hanged by judicial execution.

Declaration of the death of Amelia Dyer for murder, by the coroner and jurors, 10 June 1896 (catalogue reference: HO 144/267/A57858B)

The majority of coroners’ records, like Petty Sessions and Quarter Sessions records, are to be found in local record offices. An essential tool for locating these records is ‘Coroners’ Records in England and Wales’, by J S W Gibson and C Rogers (The Family History Partnership, 2009), which lists surviving coroners’ records by county, and includes a section on records held in The National Archives. Some modern coroners’ records do not survive very well as many have been sampled, or completely destroyed. Where they do survive, modern inquest records are closed for 75 years. Records over 15 years old could be destroyed or sampled by the coroner, but this was discretionary, and a coroner might choose not to destroy any records at all. Coroners’ offices appear to have transferred all surviving inquest papers created before 1960 to local record offices, and most inquest papers created between 1960 and 1970. It is therefore necessary to check with the relevant record office as to which records have been deposited.

Coroners’ registers of reported deaths should be preserved in local record offices and all inquest files. Where the volume of these files may be too great, the bulk may have been reduced by preserving only the key documents; that is, the inquest form and police report for all inquest cases. For very recent inquests, which are closed to the public, people who have a proper interest in the inquiry can apply to the coroner to see the coroner’s notes. They can sometimes have a copy on payment of a fee. This only applies to a relative (a parent, spouse or child of the deceased), an insurer, the police or anyone deemed by the coroner to have a proper interest.

If coroners’ records survive and have been transferred to a record office, and are over 75 years old, there are a number of documents that you may find for each particular inquest. The most important is the inquisition as it is called, which is the inquest pro forma recording the details of the deceased and the verdict of the court, signed by the coroner and the members of the jury. A pro forma precept issued by the coroner requiring court officers to summon witnesses is also usually included, listing those people called to give evidence. A police report or memorandum to the coroner will give details of the circumstances of the discovery of the body and statements from any witnesses. There may be a medical report if a post mortem was undertaken, but more often with 19th and early 20th century inquests there is just a brief report or letter from the doctor summoned to examine the body.

Where the inquest itself does not survive, journalists’ reports of inquests often appear in local newspapers to be found in local record offices and reference libraries, or online at the British Newspaper Archive. Whether they reported a particular case was up to them and 19th century reports are usually brief, but some can be extremely detailed, particularly if the death was shocking or gruesome.

Dr Katy Chater’s podcast on Coroners’ inquests gives social and family historians a number of insights into the wealth of material to be gleaned from these records. An inquest could involve many in a community, not just the coroner and jurors, and witnesses, but the family, friends and neighbours of the deceased.

As you say modern Coroners’ inquests records can be found amongst departmental files at The National Archives including most investigations into air accidents which are open after 30 or so years, however some like the inquest into the 1974 bombing at the Tower of London (MEPO 26/252, which include a transcript of coroner’s inquest and statements) is closed for 84 years and others like the inquest into Fred West’s death in custody (HO 336/693) and MEPO 2/10622 (which includes a transcript of the inquest into death of Kevin Gately injured during demonstrations in Red Lion Square, WC1 on 15 June 1974) are open. There is one other set of inquests that are open and that is for Treasure Trove which has been the responsibility of coroners to decide upon for a very long time.

[…] techadmin on March 15, 2016 Coroners’ inquest records2016-03-15T09:27:46+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

I am attempting to locate the records of a coroners inquest which took place on October 22nd, 1969 at Guisborough Court House, North Yorkshire/Cleveland.

The inquest, including evidence from Cleveland Coroner Mr. Bernard Wilkinson, pathologist Dr. Richard E Petts and Guisborough Chief Inspector Peter Wilfrid Earnshaw, concerned the unidentified remains of a male body discovered on the foreshore at Cowbar, Staithes on the North Yorkshire/Cleveland border.

The Teeside Coroners office have told me: ‘We’ve searched Teesside Inquests Sept – Dec 1969 and then the whole of 1970 and there’s no sign of an Inquest for the unidentified person.The separate Cleveland Coroners collection we hold doesn’t start until the mid 1980’s.’

And have suggested an enquiry should be put to the National Archives. Where should this be directed?

Hi John,

Please go to the ‘contact us’ page on our website: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact-us/

You’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by phone, email or live chat.

Best regards,

Liz.

I am looking to access my sisters information regarding her death from 1963.

I live in Australia and am struggling to find out what is required/if it is possible to gain access

Hi Lynn,

Thanks for your comment.

Sorry, we can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email, live chat or phone.

Best regards,

Liz.

[…] From the 15th century to 1752 the duties of the coroner were handed over to Assize Judges who returned their verdicts to the King’s Bench. From 1752 county coroners generally handled the coroners court cases and sent their finding to the Quarter Sessions. Like many British systems it is quite complex with many exceptions so it is best to work on a case by case basis. National Archives has a guide to Coroners Records Click Here to access the guide and they also have a webinar about the work of the Coroner Click Here to access the webinar. Plus a blog post on the National Archives website concerning Coroners Courts is well worth reading. Click Here to access. […]

I wish to ask if Fatal accidents in Shipyards between 1870 and the last century would have been subject to coroners court and where such records can be found?

I am looking for inquest record and subsequent coroner’s records of an accident which happened at 1 Palmer Street , Spitalfields between 16 and 21-11-1858.

A mr. Baker held an inquest info deaths of my family members being and adult and a baby. That inquest was held at the Duke of Weillington Tavern. Found some newspaper articles but would like to know more so those documents are important.

Hope someone can give me mopre information and/or point me in right direction.

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to historical research, please use our live chat or online form.

We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.