With the introduction of the Fine Arts Copyright Act of 1862, individuals and companies could for the first time register photographs, paintings and drawings for copyright protection with the Stationers’ Company. The records created as a result of this legislation – entry forms and attached images dating from 1862 to 1912 – are now held at The National Archives in record series COPY 1.

The collection presents many fascinating opportunities for research into art history, business history, visual culture and social history, to name a few. PhD student Sam Čermák joined The National Archives for a 10-week placement to conduct an in-depth exploration of the early images in the collection. In this blog, Sam gives a sense of the experience of researching the COPY 1 collection and discusses some of the most surprising and beautiful images encountered along the way.

– Katherine Howells, Principal Records Specialist, The National Archives

I leaf through pages upon pages of copyright registration forms. Some with attached carte de visite photographs – a small format of photograph popular in the 1860s shaped like visiting cards – some with no photograph attached at all. Another man in a suit leaning against a banister. Another clergyman reading a book. Another royal in a stately pose and ceremonial garb. Another woman in a dress with billowing skirt. Another… wait, no. I come across an image of an old stone cottage with a woman working in front of it. I turn the page and I see a serene forest scene with a creek cutting its way through rocks and forest on both sides. I turn it again and I see a mill on the side of a hill set in a forest with rivulets of waterfalls cutting through the rocky hillside. These photographs are beautiful and were photographed for the sake of making art. I accidentally came across photography made not for posterity or vanity but made for aesthetics, beauty, and enjoyment. Photographs made as art.

I exaggerate. By now, I’m only 190 photographs into COPY 1/1 which houses the first three months of documents created in response to the Fine Arts Copyright Act of 1862 – a very progressive piece of legislation which enabled the copyright of photographs, paintings and drawings. The record series COPY 1 holds copyright registration forms from the Stationers’ Company for these types of works between 1862 to 1912. The images registered here were in response to the needs of copyright – that is, usually made for reproduction and profit instead of images made for personal sentiments.

I did not go into the copyright collection expecting to find the beautiful. I was wrong. A series of photographs captured by a Manchester-based photographer Robert Jackson abandons the need to use photography as a documentary tool or a way to replace portrait paintings and instead captures nature and working-class life in North Wales as art. Jackson photographs three types of subject in these images. The first one is nature, the second one is rural labour, and the third is history.

The natural

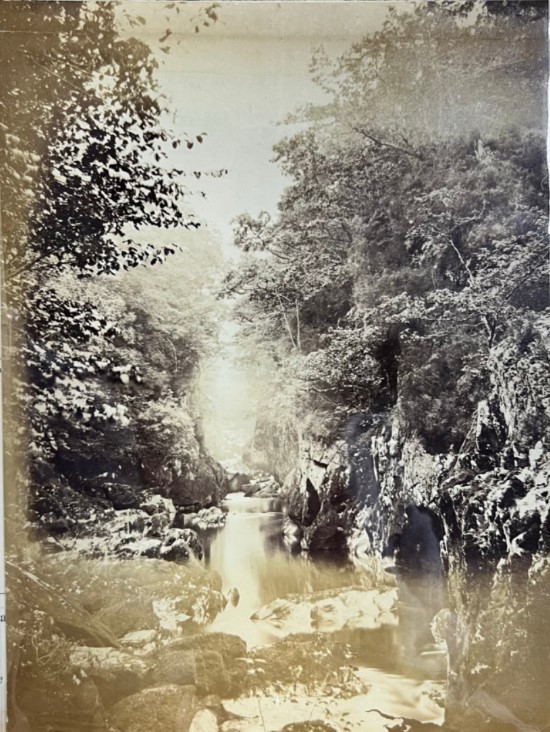

Jackson captures Welsh nature as beautiful in COPY 1/1/193, for instance, which is described characteristically dryly in the original form as ‘A photograph of Fons Nodd Ddufn near Bettws-y-coed, North Wales’. That is a great piece of information for registering copyright protection with reproduction in mind. What it fails to do, however, is respond to its beauty. Unlike other images that I found in this collection up to this point, these photographs capture and frame objects for the sake of their inherent beauty.

In this image, for instance, a stream that cuts its way across a rocky forest is framed by jagged rocks with trees growing on each side. Down the middle is a blurry stream of water, blurred by the relatively long exposure at this time (by the 1860s, the time to take a photograph was down to a couple of seconds), and a streak of bright sky where the two forests reach towards each other but their branches fail to meet.

The image looks like travel photography but it doesn’t feel documentary. Instead it seems to me indisputably artistic. What Jackson captures here is not a document of a river, although it does also document the forest at that particular moment in time. What his photograph captures is a meticulously framed image with a high consideration of composition to achieve a particular effect – one which sitting in the reading room of The National Archives appeals to me as undeniably artistic and beautiful.

Fleeting rural labour

My favourite images are his photographs of rural life in Wales. COPY 1/1/191 is a beautiful image of an old stone cottage with its roof overgrown with foliage. A woman wearing a working dress is standing in the middle of the image, looking off to the right with an empty cart behind her. In the upper right corner is an open wooden gate in the middle of a stone fence. The image feels idyllic. It’s a very welcome break for my eyes from the myriad images of aristocracy. A rural scene of work and calmness.

Unpredictably to me, Jackson’s description of the image for the purposes of copyright captures the woman’s name as well: ‘A photograph of Mrs Williams and her cottage near Bettws-y-coed, North Wales’. I say unpredictably because I saw a total of 1,558 images while researching at The National Archives, with very few images of the working classes, and Jackson was the only one I found who wrote down the names of the people he photographed. Jackson seems to have cared about the rural not only for its visual value but also about the people who occupied and embodied rural life at the time. The woman in the image is not simply ‘a woman’ to him but she is her own person: Mrs Williams who works near her cottage.

The historical

The final category of images here is that of history, exemplified here by ‘Conway Castle’ [sic] in COPY 1/1/192 (this is Conwy Castle, but spelled Conway Castle in the registration form submitted with the photograph). The photograph is taken across the water with the suspension bridge leading to the castle on the left. Once again, the water is smoothened and blurred by the relatively long exposure time. The castle towers in ruin across the moat with parts of it overgrown by ivy and trees. The reflection in the water is soft, like an image in a gently disturbed puddle of water.

Out of these images, Conwy Castle feels the most financially viable as a souvenir or an illustration for an article or a travel journal. The photograph looks surprisingly a lot like contemporary photographs of tourist attractions, with only one person visible on the image standing in the middle of the suspension bridge. Nonetheless, Jackson once again frames it carefully as an art piece instead of a document. What he captures is the ordinary beauty in a castle in ruin.

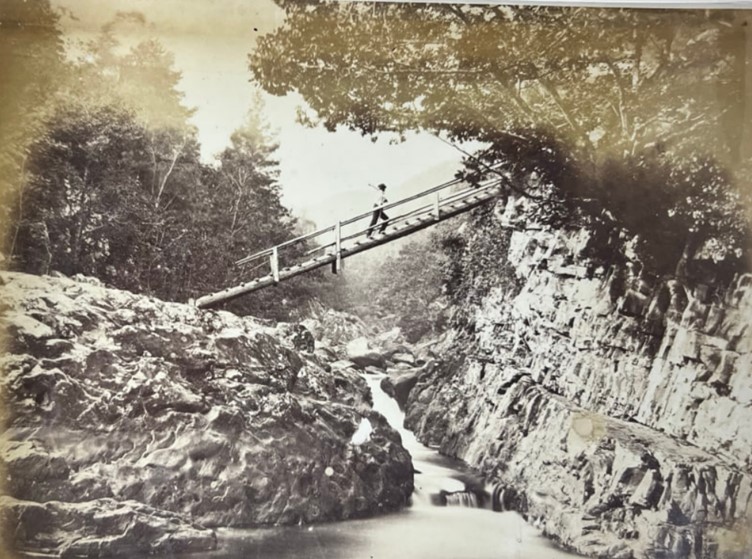

There are too many beautiful photographs by Jackson in this collection to point to in this blog. Whether it is the Miller’s Bridge that he captured in Wales, the quaint and beautiful images of a mill with a miller and his wife working, or other images of nature, Jackson’s images are pictures that capture beauty for the sake of artistic pleasure. Unlike the cartes de visite that dominate COPY 1/1, Jackson’s photographs are not only for the sake of posterity or reproduction. They can undoubtedly fulfil an economic function as well – after all, there was and still is an art market and carte de visite implicitly referenced or participated in it as well. Nonetheless, looking at his images, I am struck by their beauty – one which I did not quite expect to find at this point in the archive. Beauty of the ordinary, the natural, the old, and the fleeting.

Sam Čermák (he/they) is a doctoral candidate and teaching associate at Queen Mary University of London researching Czech and Slovak performance art from the 1960s to 1989 with a focus on disentangling national identities within art historical narratives. You can find Sam on Twitter at @Sam_Cermak.

To find out more about the Copyright Collection held at The National Archives, and for advice on how to access it, please see our research guide to Intellectual property: photographs, artwork, literature, music and advertising registered for copyright 1842-1924.

Some great images displayed, showing the rich and unexpected finds we have in the archives. The library has a number of books on photography from the early days to more current techniques, including monographs on conservation and preservation of photographic images and film. You can find them in our catalogue (https://tna.koha-ptfs.co.uk), searching for photography (of course!) or via the list of resources we have created – https://tna.koha-ptfs.co.uk/cgi-bin/koha/opac-shelves.pl?op=view&shelfnumber=330

This is striking stuff. I hope TNA is considering digitizing all the Jackson photographs.

Interesting. I spent most of my (very successful) working life in the photographic trade, retired at age 55.

it was not really Art which drove these folk to make images of their local areas, but obviously they were intrigued by the process of photography (all new DIY technology in those days) So was mine, it started when i was about 10 years old and an uncle showed me how to print images from old negatives on P.O.P (printing out paper) in sunlight

and if they had the spare cash to do more no doubt that would make big difference. Most folk were sadly limited to the odd picture or two on special occasions!

I find these photographs of the 1800’s very interesting, especially in the countryside, they make my imagination run wild, I want to know more about Mrs. Williams and how she spent her days, and what it was like living in those enchanting, but hard conditions. I’m just a Townie of 92yrs, that I would swap for experiencing that way of life.

This is a well written article by the author. I love reading history is always interesting to learn more.