In my previous post, Constance Markievicz: The making of a rebel Countess, I explored the influences and events that were essential in the development of Constance Markievicz’s political career, leading up to the point in which Republican groups had set a date for their revolution.

What followed – the events of the 1916 Easter Rising – almost ended Markievicz’s life, but as we will see, the rebel Countess was just getting started. Even after her release from prison for her involvement in the rebellion, Markievicz continued to campaign for Irish independence, and served a further five terms in prison for offences connected to it.

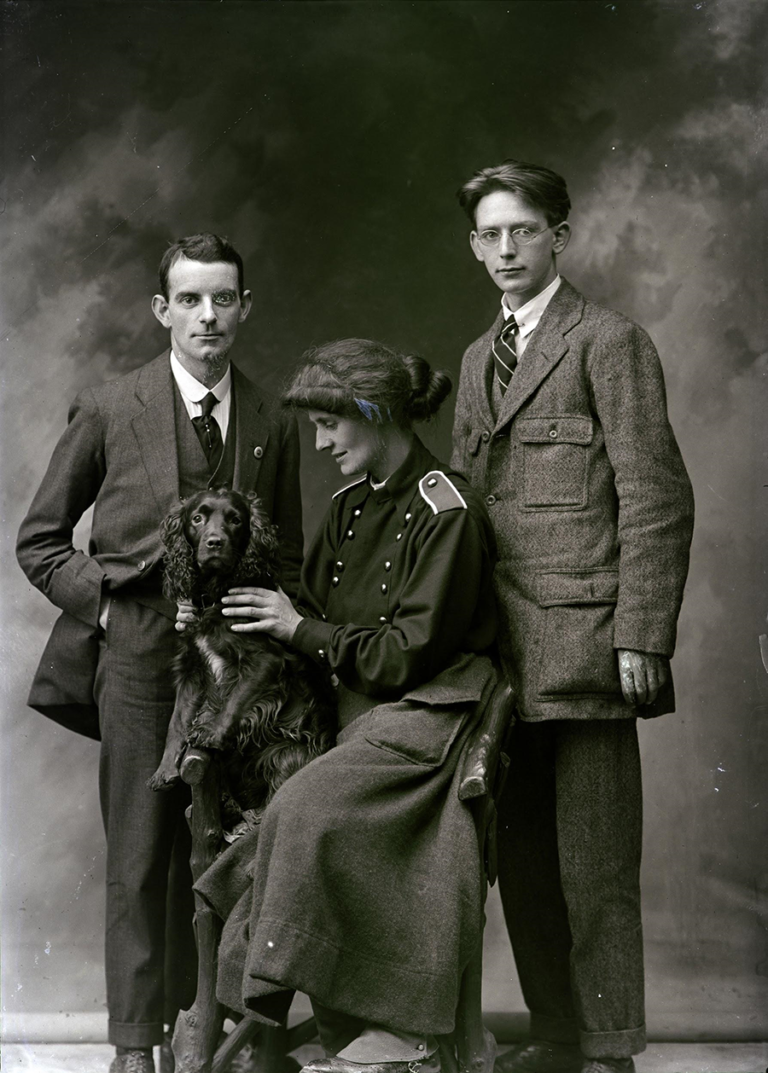

Markievicz’s active roles across various republican organisations ensured her place alongside the high-ranking leaders of the revolution. In preparation for Easter weekend she aided James Connolly and the Citizen’s Army, mobilising volunteers and ensuring the distribution of arms to all involved[ref]An ICA member wrote ‘I can remember seeing her marching at the end of the Citizen Army with Connolly and Mallin at a parade one Sunday afternoon. My God, she was it’ (Haverty, 138).[/ref]. In a letter to Cuman na mBan (The Irishwomen’s Council) sent while in prison in 1917, Markievicz provides insight into the significance of her revolutionary role:

‘I was accepted by Tom Clarke and the members of the provisional Government as the second of Connolly’s “ghosts”. “Ghosts” was the name we gave to those who stood secretly behind the leaders and were entrusted with enough of the plans of the Rising to enable them to carry on that Leader’s work should anything happen to himself.’

Prison Letters of Countess Markievicz, Virago, 38

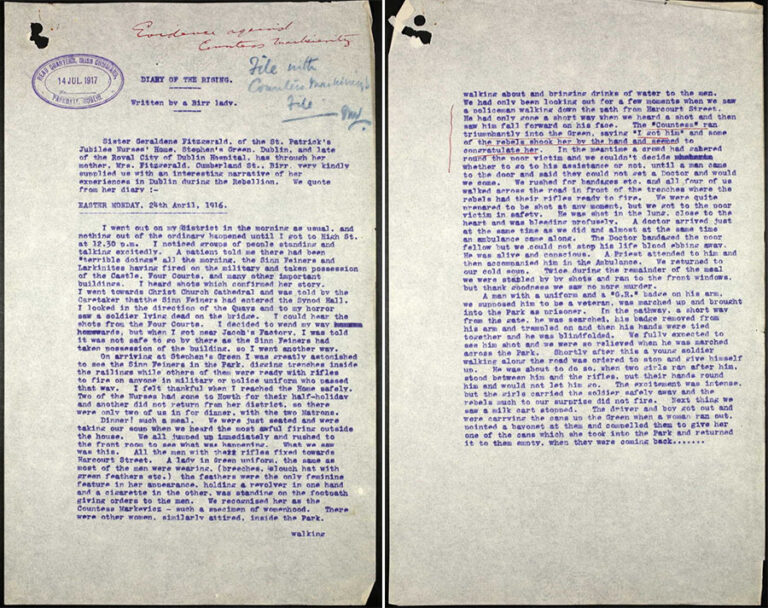

The Countess was stationed between the Royal College of Surgeons and St Stephen’s Green during what became a bloody week of fighting. While ensuring that volunteers and Fianna boys were armed, fed and always prepared, Markievicz herself did not hold back, fighting alongside the men where necessary. A diary extract provided as evidence during her court-martialing reveals:

‘We recognised her as the Countess Markievicz – such a specimen of womanhood […] We had only been looking out for a few moments when we saw a policeman walking down the path from Harcourt Street. He had only gone a short way when we heard a shot and then saw him fall forward on his face. The “Countess” ran triumphantly into the Green, saying “I got him” and some of the rebels shook her by the hand and seemed to congratulate her.’

Catalogue ref: CO 904

After six long days which saw much of Dublin city centre destroyed, many dead and thousands injured, nationalist forces surrendered. Along with the other rebel leaders, Markievicz was arrested and taken to Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin where she was charged with ‘taking part in an armed rebellion’, court-martialed and sentenced to death for her participation. At trial the Countess admitted to the charges and was reported to have declared: ‘I told the Court that I had fought for the independence of Ireland during Easter Week and that I was ready now to die for the cause as I was then’[ref]Freeman’s Journal, 19 June 1917.[/ref].

But despite the initial sentencing and her own persistent martyrdom, Constance Markievicz did not face the same fate as her fellow revolutionaries, on account of her sex. Over a 10-day period in May 1916, 14 rebels (namely those that had signed the Proclamation of the Irish Republic) were executed by firing squad in the yard of Kilmainham Gaol. One of the last to be shot, comrade and friend James Connolly, had been so badly injured during the rebellion that he had to be tied to a chair before his execution.

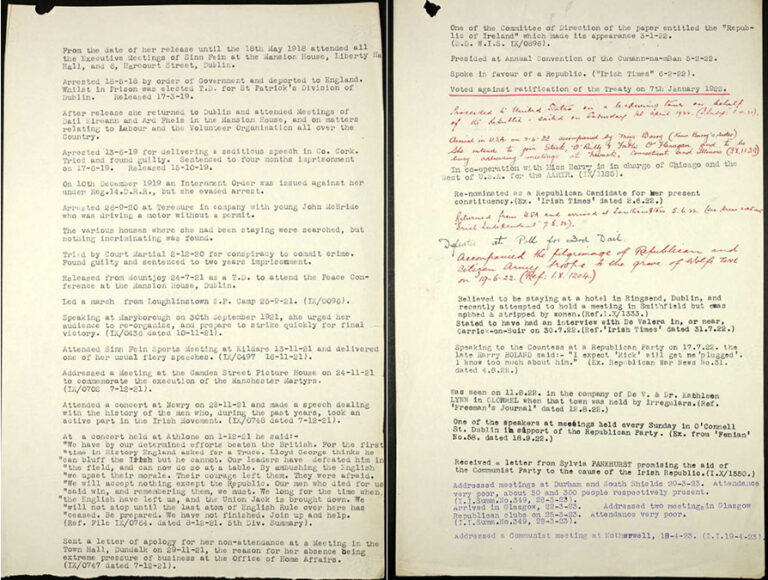

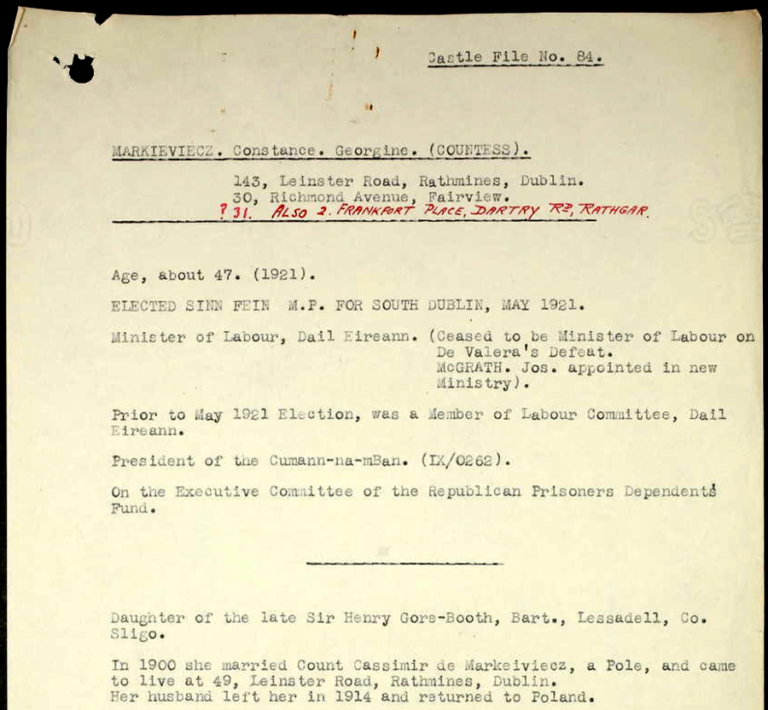

The Dublin Castle Papers shed light on Markievicz’s fate, stating that ‘she was sentenced to death, which was afterwards commuted to penal servitude for life, for her part in the Rebellion, and was released in the General Amnesty of June, 1917’ (CO 904). The Countess’s arrival in Dublin following her release from Aylesbury Prison was a momentous occasion and she was hailed a revolutionary hero.

‘I thank you more than I can say for the welcome back to Dublin that you have given me – I find Ireland rebel at last – (loud cheers) […] We shall all go on working until Ireland is Free once more (loud and prolonged cheers and shouts) […] I will now only say goodnight to you but we will meet again – to-morrow – the next day – and every day – and we will all go on working until we die and until Ireland is a Republic.’

‘Speech of Countess Markievicz on 31-6-17.’ Catalogue ref: CO 904 (Dublin Castle Papers)

It was not long before Markievicz would be back in prison. She was ‘arrested in 1918 by order of the Government and deported to England’ (CO 904), and this is how she would spend the rest of her years until she died – between prison and politics – while she continued to campaign for Irish independence. Incarceration would not stop her, and the documents held at The National Archives reveal that her activities in and out of prison were closely monitored.

It was during her time in Holloway Prison that Markievicz, a Sinn Féin candidate for Dublin St Patrick’s ward, beat opponent William Field to become the first woman elected to British Parliament. However, in line with the party’s abstentionist policy, and along with 72 fellow Sinn Féin MPs, the Countess refused to take her seat. She was also unable to take her seat as part of the First Dáil (Irish Revolutionary Parliament) due to her being incarcerated and would have to wait until her release before being re-elected as part of the Second Dáil in 1921. Throughout this period (1919-1921) she also served as the Dáil’s Minister for Labour, making her the first Irish female Cabinet minister and the second female government minister in Europe.

Opposing the Anglo-Irish treaty of 1921, the Countess would leave her place in the Dáil in 1922. She toured America that same year but would later arrive back in Ireland to a bitter division in the Republican party, and amidst the Irish Civil War[ref]Not all Republicans opposed the Anglo-Irish treaty. While many, like Markievicz or Éamon de Valera, were against the agreement and refused to pledge an Oath of Allegiance to the king, others such as Michael Collins and Arthur Griffiths saw it as a stepping stone towards independence.[/ref]. Markievicz would spend this time hiding, on the run, or fighting in the hope of achieving an Irish Free State, but pro-treaty Republicans would be victorious. Subsequently, alongside Éamon de Valera in 1926, Markievicz would help to found a new political party – the nationalist Fianna Fáil.

Countess Constance Markievicz died at the age of 59 in 1927 following complications from appendicitis. Due to the Republican rivalries at the time, she was denied a state funeral, but crowds of admirers came to Dublin to watch her funeral procession before she was laid to rest. Since her death, Markievicz’s dedication to the Irish Republican cause has not been forgotten, and she is commemorated throughout Ireland. Today, thanks to the wealth of archival documents that are available, we are able to look back over her remarkable life and recognize her struggles, her passion and her achievements.

Imperial War Museums have a fragment of newsreel showing the Countess and Éamon de Valera addressing a crowd while campaigning for the East Clare by-election in May 1917.

The film was released when the pair, together with other prominent Republicans were arrested a year later.

It can be viewed at https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1060008282

IWM also has the oral history of Alice Gray who was a schoolgirl in Ireland during 1916 – 1920 and describes the activities of Constance and her own recollections of Constance’s daughter Maeve together with other events in Sligo at the time. This can be heard at https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80014785.

I visited Lissadel In the1960’s where I met Gore Booth who was playing on a grand piano in the large window (which I guess was the window in Yeats’ poem …). Toured the amazing house for a payment of £1.