As a part of my conservation training at the Institut National du Patrimoine school in Paris, I completed a six month student placement at the Collection Care department from February to July 2017.

This placement was an amazing experience. I was involved in several conservation projects on medieval parchments, Civil War papers and Second World War maps, and I witnessed several aspects of working in archives, including surveys and preparing documents for loan. I also applied my scientific knowledge in finding a new solution to a conservation issue. I will leave The National Archives in a few days feeling more confident in my technical skills and with a greater appetite for research!

What I really enjoyed here is how conservation and science are close. Facing a conservation issue with one of the documents I worked on, I had the exciting opportunity to work with the conservation scientists to find a solution. The record concerned is a testimony of local history, correspondence of the General Board of Health between 1848 and 1871 (MH 13/234), at a moment when health policies were developing. The 19th century was a real turning point, as the government implemented laws and local administrations to prevent epidemics like cholera. We can find in number 234… Richmond-Upon-Thames, where The National Archives is now located!

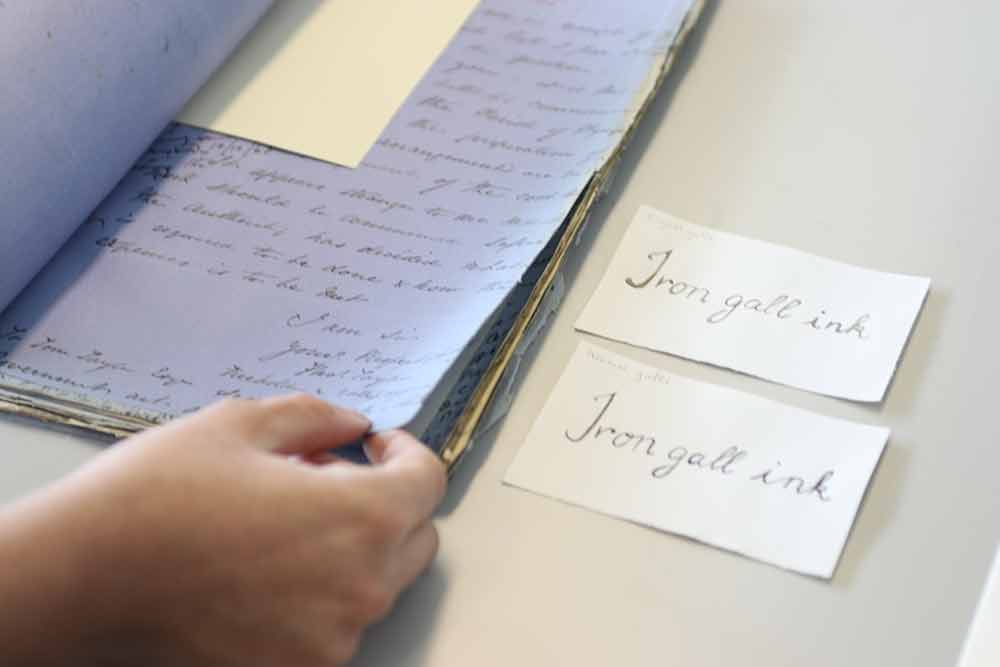

The register is made of letters written in iron gall ink on several types of paper (blue paper, transparent paper). Some of the pages were pasted together, hiding the text underneath.

Studying the register of letters

Using a scientific technique called Fourier Transform Infra-Red spectroscopy the adhesive was identified as wheat starch paste. Usually we use water to separate pages stuck with wheat starch paste, but iron gall ink made this complicated.

Iron gall ink was first mentioned by Pliny the Elder in AD23. The main ingredients are oak galls and iron (II) sulphate, both of which can make paper brown and brittle. To make things worse, it contains iron ions that can move further through the paper because of humidity and cause even more degradation.

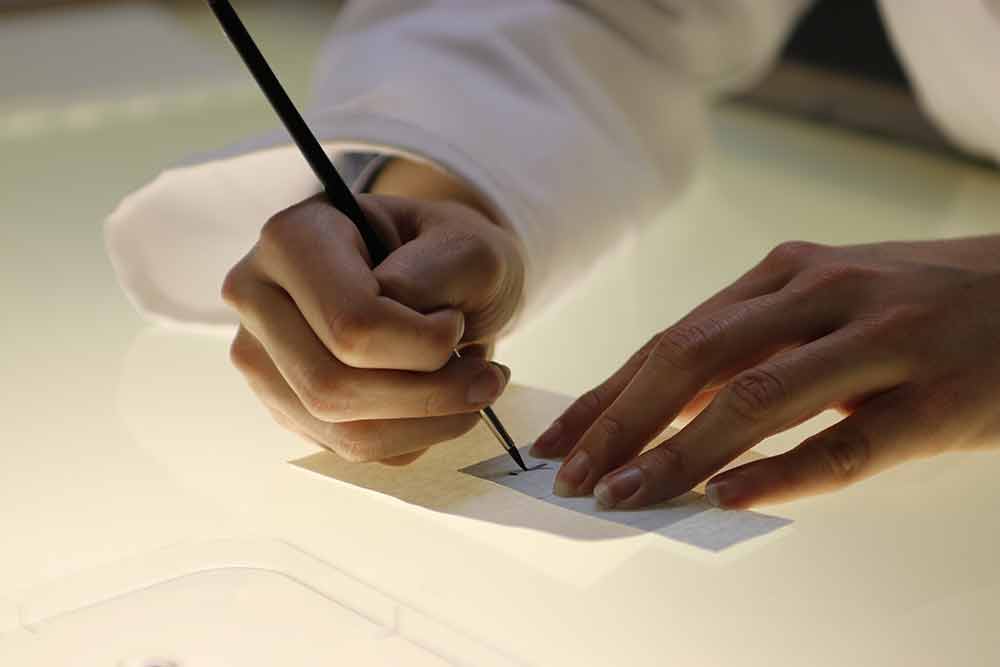

We decided to make our own iron gall ink and tested subtle ways of introducing moisture: a water permeable membrane (Porelle®), enzymes (Albertina Kompress) and gels (Gellan gum).

Writing out the iron gall ink samples

In the end gellan gum, a rigid gel that is used in the food industry, gave the best results. It was efficient at separating the pages without affecting the inks. Once the solution was found, treatment could begin!

The register was first dry cleaned with smoke sponge to remove the dust. Then all the tears were repaired with a Japanese tissue and gelatine adhesive. Finally, the pages were separated using gellan gum.

Being involved in many conservation projects has allowed me to improve my technical skills and has given me the opportunity to work on fascinating documents. The frequent workshops organised by Collection Care staff helped me discover new conservation methods. This placement had been highly recommended to me by two students who came here before me, and the experience was even better than I expected!

Many thanks to Alison Archibald, Helen Wilson and Jacqueline Moon for their supervision of this project and their help in writing this blogpost.