Over the past ten weeks, I have been on a placement at the National Archives as part of my Public History MA course at St Mary’s University, Twickenham. During my time here I have been looking at the records of the Middlesex Military Service Tribunal, paying particular attention to the cases heard in Twickenham from conscientious objectors.

Having lived in Twickenham for three years while completing my degree, I wanted to find out more about the people who had lived there 100 years ago and see if there were any interesting stories to be told.

The tribunals

When war first broke out in 1914 a large number of men volunteered to join the forces. Two years on, with army numbers declining, the military were in urgent need of recruits.

On 27 January 1916, the Military Service Act was passed, meaning that all men between the ages of 18 to 41 were liable for general service in the army. They were able to apply for exemption from military service and there were seven grounds to base an application on, the majority of which focused on domestic or educational reasons.

One of these grounds for exemption was a particularly contentious issue: conscientious objection. It had the ability to divide the public and force some men into harsh situations on account of their beliefs.

The applications for military exemption were heard before a local tribunal comprised of mostly men, who were expected to satisfy all sides, the military, the government, and of course, the man applying for exemption. Each appellant would get around five minutes or less to state his case and, after a brief discussion, a decision would be made. If the appellant was dissatisfied with the local tribunal’s verdict he could take his case further, to the county tribunal. When it came to appeals on conscientious grounds, the tribunals would have to decide if a man showed genuine conscientious convictions. The tribunals presumed that objectors would have mostly religious or spiritual reasons behind their beliefs and those who did not demonstrate these qualities were not granted their exemption.[ref]1. James McDermott, ‘Conscience and the Military Service Tribunals During the First World War: Experiences in Northamptonshire’, War in History, 17/1, (2010), 63-68[/ref]

After looking at these applications, I was interested to find out about those who, after applying to the Middlesex Tribunal, were still not granted exemption. After his case was dismissed, a man was considered to be a member of the army reserve and was called up based on age and medical status. It was the ultimate catch-22 for conscientious objectors: they could either join the war – something that they deeply disagreed with on religious, moral or political grounds – or suffer the consequences of army justice, which could be as extreme as a death sentence.

I have discovered the stories of two conscientious objectors from Twickenham who were faced with this difficult decision and whose wartime experiences ended very differently.

‘I refuse to murder and butcher people’

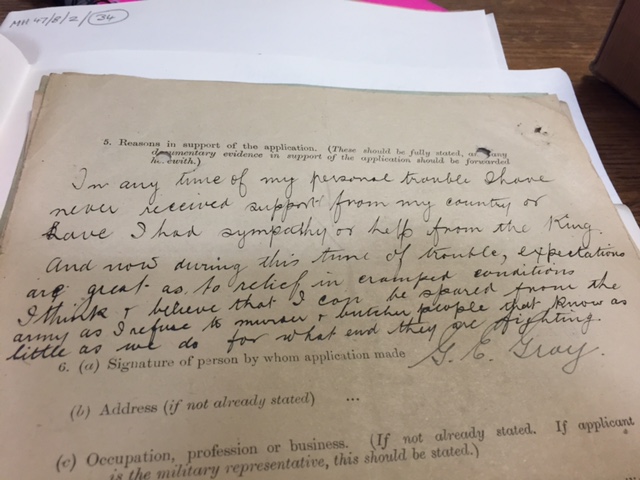

Gerald Gray was 22 when he applied to the Middlesex Tribunal for exemption. At his local tribunal, he had two main reasons for his views against the war. He stated that he would not butcher and murder those who, like him, did not understand the reasons for the war or what outcome they were fighting for.

His other, more provocative statement was that when he had experienced personal troubles he had never received any help from the king or his country, and now that Britain was at war their expectations of him were great.

The tribunal found no reason for Gerald Gray to receive any form of exemption. He did not belong to a religious sect found to have objections against warfare, nor did he provide any evidence of his beliefs. They dismissed his case. He did attempt to appeal again to the Central Tribunal but this was disallowed (MH 47/8/91).

Gerald Gray’s application to the local tribunal (catalogue reference: MH 47/8/91)

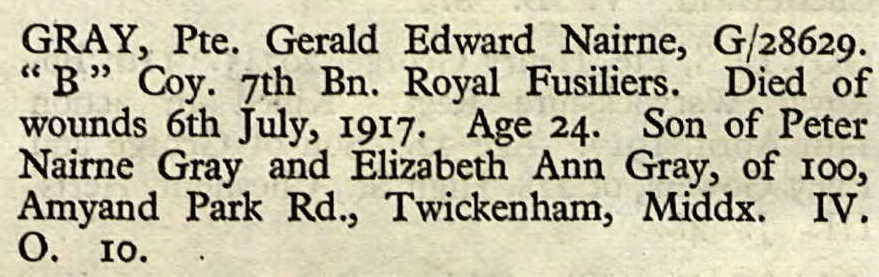

After a bit of digging around in the archives I discovered that Gerald Gray, despite his objections to war, went to France to fight; he was a private in the 7th Battalion Royal Fusiliers. On 5 July 1917 his regiment was hit with heavy artillery fire leaving 12 dead, six injured and one with shell shock.

On 6 July 1917, Gerald Gray lost his life due to the wounds he had received in France. He was just 24 years old (WO 95/3119/1). Details of his death can be found on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website.

Gerald Gray’s entry on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

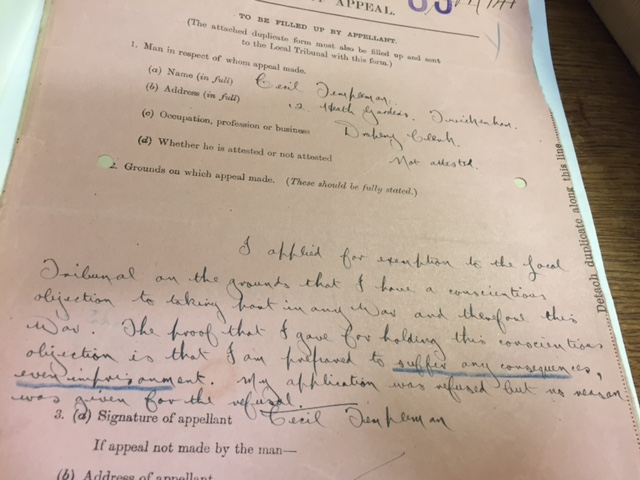

In contrast to Gerald Gray’s case, Cecil Templeman decided not to join the war effort after his case was dismissed. He applied to his local tribunal and said, ‘in no way will I assist the military machine, because I believe all war is wrong and contrary to the teaching of Jesus Christ’.

In his appeal to the Middlesex Tribunal he stated that he was prepared to suffer the consequences, even imprisonment, should this appeal be refused. He tried to appeal again to the Central Tribunal on 24 March 1916 but this was disallowed (MH 47/8/96).

Refusing to concede his beliefs and help the war effort in any way, Cecil Templeman was arrested on 2 April 1916. His record can be found on the Lives of the First World War website from the Imperial War Museum. It shows that in a clear demonstration of his feelings about the whole affair, he threw his boot at the magistrate after his trial.

Cecil Templeman’s appeal to the Middlesex Tribunal (catalogue reference: MH 47/8/96)

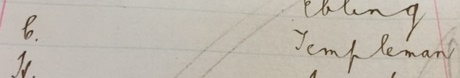

On 18 April 1916, Templeman received a Court-Martial. He was charged with Insubordination and Disobedience and a Plea in Bar was allowed. This meant that he was unable to enter a plea or provide his own defence and therefore was automatically found to be guilty under the Military Service Act. Templeman was sentenced to one year imprisonment which was commuted to 112 days. He was discharged from the army with disgrace (WO 86/69).

On 8 August 1916 Templeman appealed once again to the central tribunal and was released to the Brace Committee, an organisation set up to deal with the growing number of inmates who were imprisoned due to their conscientious beliefs (MH 47/1/2).

Cecil Templman’s entry into the District Courts Martial Register (catalogue reference: WO 86/69)

The committee recommended setting up Work Centres where prisoners could stay and work for the remainder of their sentences. The conditions were designed to be just as bad, if not worse, than those experienced by soldiers at the front. The work was gruelling and illness was rife with many prisoners not used to the hard labour having come from mostly administrative backgrounds.[ref]2. Simon Webb, ‘British Concentration Camps: A Brief History from 1900-1975’ (Barnsley: Pen and Sword History, 2016), 58-59[/ref]

Cowards or shirkers?

There was a view at the time that conscientious objectors were cowards or shirkers who used these grounds to abstain from their military responsibilities. After discovering more about their stories it is clear that neither man could be given these labels.

To stand up and object to war based on conscientious reasons was an incredibly brave thing for a man to do, especially in the face of criticism from society. Gerald Gray’s story shows us that some conscientious objectors did fight in the war, despite their moral beliefs, and in this case, Gray ultimately lost his life. Others, like Cecil Templeman, refused to help the war in any way but instead ended up in a labour camp serving a prison sentence. Both men sacrificed a great deal during the war and their courage should not be overlooked.

Most tribunal records were destroyed after the war, but the Middlesex records are one of the few survivors. It is these records that are kept here at the National Archives under reference MH 47, and the project page includes a list of surviving material elsewhere.

When looking at these records, as I have discovered, you never know what you might find.

Related blogs

Decision time: Military Service Tribunals 100 years on

A very interesting blog, this and well worth researching

Why not put it on stage? Some of us did just that for one Ernest Everett who was the first man in England to get two years for hard labour. Fearfully amateur production, but it has some interesting bits nonetheless and you can see it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vGI8cV8zGO0

A very interesting account of two very contrasting outcomes to conscientious objection. I have recently had printed by the Borough of Twickenham Local History a paper on appeals at Hampton Wick against enlistment into the Army in the First World War (“I have a weak heart and military service would knock me up”). Hampton Wick was formerly in the Borough of Twickenham. In going through the local newspapers I came across several mentions of Cecil Templeman and have quoted one of these in my paper.

My great-uncle Walter Crozier’s appeal papers are in MH 47. He was another Twickenham resident and his case was perhaps a more typical case before the Tribunal. Over an eighteen month period he appealed against conscription on no real grounds – he certainly wasn’t doing work of national importance, he did not have a family to care for and he was not a conscientious objector. The tribunal bent over backwards to accommodate him and his non-appearances, but eventually they ran out of patience. After an uneventful service career he was discharged in 1919 and lived well into his seventies near Twickenham station.

Fascinating blog that actually hits quite close to home to my family. My late grandfather David McCatt Snr also argued his case for not going to war but in Gillingham where the records were sadly destroyed. According to my father David McCatt Jnr his main point of arguement was rather than any conscientious objections (infact he gained somewhat of an infamous reputation locally as a man so enamored with the idea of war that he recieved a court injunction ordering him to remain at least 50 paces from cannons and other war antiquities after what he always maintened was just a clothing malfunction in a museum) it was actually that he had no thumbs so was unable to fire a weapon.

His hearing appeared to be heading in his favour until of course his former friend, neighbour and local candle stick maker business rival Stuart Basoon of Basoon Wax Emporium and Gun Modifications and Sons informed the committee of his new invention. On the 10th of August 1916 the world (well, Gillingham) was very briefly and oddly introduced to the brand new Basoon Toe Musket understood to be the worlds first toe triggered gun. After a brief but rupturous round of applause my grandfather was denied his request to be left out of the war and packed off that week Musket in foot to the continent. He was killed almost immediately and the weapon was widely considered horrificly inadequate although historically funny.

Within a week my grandmother Davina McCatt had not only married but also signed over the family business of McCatts Candle Stick Makers and Vintage Cannon Cleaners to Stuart Basoon as they used their unholy union to create the 4th largest candle stick manufacturer in Gillingham and my father was left abandoned at a local orphanage.

War is hell.