I started volunteering at The National Archives in September 2018 as part of an on site volunteer team on the Navy Board cataloguing project. I was keen to learn more about the Royal Navy and maritime history. The work has been fascinating and I have since learnt such a lot.

The project in progress when I started was near completion, and from late 2018 we have been working on the Royal Navy Captains’ Letters project, managed by Bruno Pappalardo, The National Archives’ Principal Records Specialist for Royal Navy records. As the name suggests, this project, which is scheduled to complete in 2024, involves cataloguing the letters written by Royal Navy Captains to the Admiralty, specifically during the Napoleonic Wars period (1793 to 1815). These letters are held by The National Archives in 564 boxes in the series ADM 1, filed according to the initial letter of the Captain’s surname, and by year.

When we have been allocated a Captain’s letters box our role is to read each letter and enter its details on to PROCAT editorial (cataloguing system), along with a summary of each letter’s content. Once we complete a box our work is checked and the data from PROCAT editorial is then uploaded to The National Archives’ online website catalogue, Discovery. The aim is that researchers will then be able to search these letter summaries using Discovery either by date or by entering key words – for example, a ship’s name, the name of a Captain, a place name or former Admiralty letter reference – and be able to see details of all letters which are relevant to the search term.

We were interrupted by COVID-19 in early 2020, when I was almost half way through the box (ADM 1/1621) of 325 letters and enclosures which I had been working on. My box related to Captains with a surname beginning with ‘C’, and the year 1796. The work was put on hold until the latter part of the year, when a brief relaxation in COVID precautions allowed me to fit in one session before we entered lockdown once again.

We resumed our work at the very end of April this year, and on my first day I settled down to renew acquaintances with Captain Charles Cotton, on HMS Mars, whose letters consisted of reporting his ship’s position, asking for replacement crew, and requesting expenses. Such letters are the bread and butter of our work. There is a lot of routine, interspersed with more interesting or unusual correspondence. Some letters give an insight into Royal Navy history, with involvement in battles, or the taking of foreign vessels, which often prompt me to investigate and learn more about the particular period. I find the social history which is revealed in some of the letters particularly fascinating.

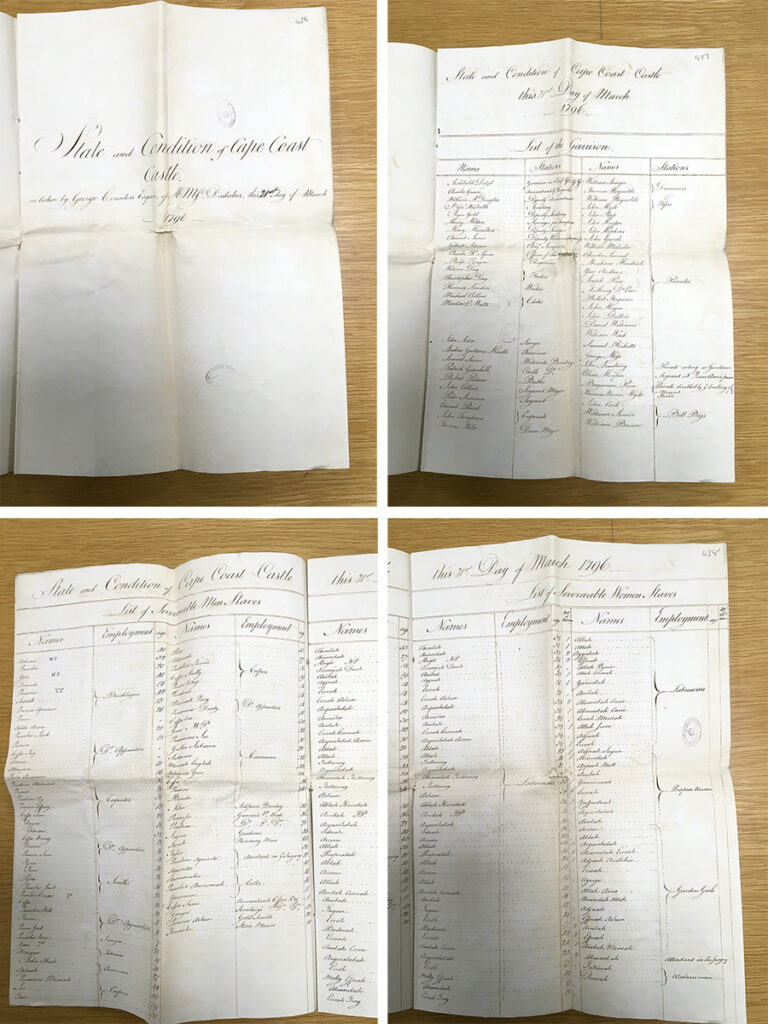

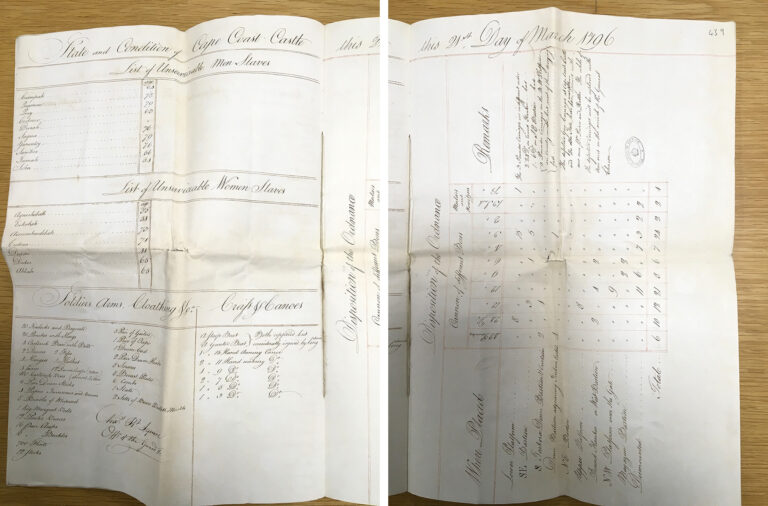

Very soon I moved on to Captain George Countess on HMS Daedalus, whose first letter in January 1796 was sent from Madeira, reporting on a convoy, but without any details of where he had sailed from. By March he had moved on to Cape Coast Castle (Ghana), where he was due to rendezvous with another Royal Navy vessel which was to pick up trade vessels at various points on the coast to form a convoy. There are two letters relating to the hazardous conditions in the tornado season and the difficulties of navigating the coastal waters for those unfamiliar with the area, but the next document was a complete surprise and an exceptional find: an 8-page, A5 manuscript prepared by Captain Countess, dated 21 March 1796, reporting on the ‘State and Condition of Cape Coast Castle’ (ADM 1/1621 folios 435-442).

For those like me, who had never heard of Cape Coast Castle, a little investigation was required. This revealed that Cape Coast Castle was one of some 40 large ‘slave castles’ or commercial forts set up by European traders on the Gold Coast (now Ghana). First established as a trade lodge by the Portuguese in 1555, a permanent wooden fortress was built nearly 100 years later by the Swedish Africa Company for the trade of timber and gold. Some 10 years later the Danes seized power and replaced the wooden fortress with a stone building. It then passed variously between the Netherlands, a local chief, and finally the British in 1664, becoming the capital of British possessions on the Gold Coast. By 1700 the fort had been replaced by a castle, and was the headquarters of the colonial governor.

Cape Coast Castle rapidly became an important market and centre of trade. The initial attraction for the Europeans was gold and mahogany, and in exchange the locals received clothing, blankets, sugar, spices and silk. At the time, however, enslaved Africans were a valuable commodity and much in demand in the Caribbean and Americas, and Cape Coast became the centre of the slave trade. As many as a thousand enslaved could be held at Cape Coast Castle prior to being embarked on vessels bound for the Americas, and large underground dungeons were built to hold the enslaved while awaiting transport. The terrible conditions in these dungeons contrasted starkly with the Governor’s apartments and offices.

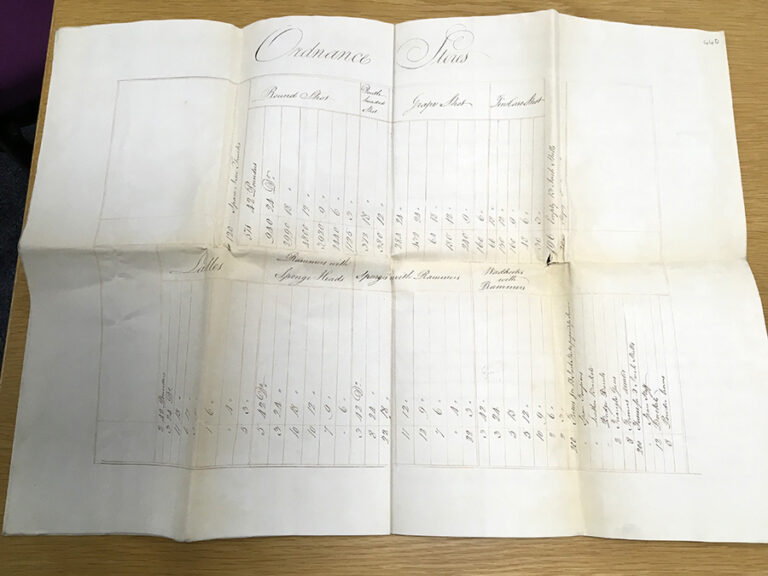

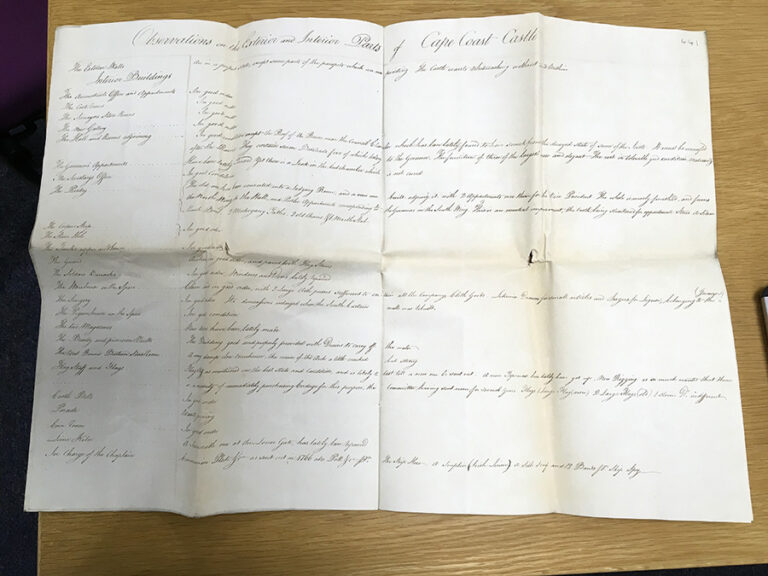

The document prepared by Captain Countess contains an extensive report on the castle. On the first page is listed the Governor and some 53 other named individuals, both civilian and military, occupying the garrison. The next two pages give lists of 75 named serviceable enslaved males, with age and trade/occupation, and 83 named serviceable enslaved females, with age, occupation, and number of children. The youngest enslaved male was aged seven and the oldest 53, and the enslaved women ages ranged from nine to 48, although one of the two columns has not been completed for age. Further pages list the names and ages of 10 unserviceable enslaved males and seven unserviceable enslaved females, ranging from age 41 to 79. The following pages of the document list the soldiers’ arms and clothing, the crafts and canoes, location of armaments, and ordnance stores. The final pages, signed by both Captain Countess and Governor Dalzel, contain observations on the external and internal structures of all the buildings, and the garden. I was particularly struck by one entry which is labelled ‘The Slave Hole’ and reported to be ‘in good order’, and another recording that ‘The Burial Ground’ must soon be changed.

There must be so many human stories behind this particular document. What happened to each of these enslaved individuals? How many survived the voyage on which they were embarked? Where did they land? A subsequent letter on 22 April reported that the convoy was sailing for the West Indies. By October, Captain Countess was reporting from Spithead, having been under the command of the Commander-in-Chief at Jamaica and subsequently ordered to accompany a convoy of homeward-bound trade vessels through the Gulf of Florida. Unfortunately, the crew was struck down by yellow fever, and Captain Countess took the vessel north to Nova Scotia with the intention of recruiting new crew and to refit the vessel.

Further comments give the clear impression that his destination had been Jamaica, but there is no reference to what happened to the trade vessels, or where the enslaved were landed. It is, however, reasonable to assume that some of the enslaved did survive the voyage and landed in Jamaica, and that they went on to have children and have living descendants.

It will be really intriguing to discover as this project continues whether answers to these questions may be found.

I, too, have been deeply engaged in these stories, but of one Captain in particular, the progenitor of a family history I’m writing. I am a book author and editor. His name is Captain Thomas Waters, so you will likely have not gotten to him yet, but we would be ever grateful if we could learn if you hold any correspondence/documents from him. Also, we are more than happy to share the letters we have, which include accounts of the numerous slave trade ships he captured as a Captain of the British Naval Marines in the 1800s. He also has rich descriptions of Cape Coast Castle, and of encountering the Ashantees (during the 1st Ashantee War). His writing is articulate, colorful and deeply descriptive. I have also made a list of all the ships he served on, and the list of their slave ship captures, dates and numbers of freed slaves.

We are working on the book to go to the editor likely January 30, 2022, so our time is drawing short. If you have anything related that you could share, we would be immensely grateful!

Hello Suzanne PASCHALL,

I am John Dotse, a PhD researcher at the University of Toronto. I am researching the African slave trade and related wars. Therefore, if you don’t mind, I would appreciate it if you could share the letters of Captain Thomas Waters, which capture the Captain “encountering the Ashantees” during the 1st Ashantee War. I would also appreciate it if you could share with me other authors who discuss the Ashantee wars if you do have them.

Thanks very much.