Over 100 Security Service (MI5) files are being released today covering a wide range of subjects and individuals. Most notably, the files offer fresh perspectives on notorious members of the Cambridge Five spy ring, namely Anthony Blunt, Kim Philby and John Cairncross.

The content of these files is fascinating – they include transcripts of interrogations, and of bugged telephone calls, surveillance reports, memos, reports, and correspondence – items that were considered ‘Secret’ or ‘Top Secret’ for so many years. This release, therefore, brings us rich layers of extra detail that can be added to the ‘known’ story.

Who were The Cambridge Five?

Harold ‘Kim’ Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross formed the most infamous spy ring of the 20th century: the Cambridge Five.

They are commonly referred to as a ‘spy ring’, which suggests a cohesive unit. This is a misnomer, however, as although there was cross-connection and co-conspiracy between them, they took separate paths and operated independently to a significant degree. But they certainly had this in common: all were graduates of Cambridge University, and were recruited by Soviet Intelligence during the 1930s.

During the Second World War and after, they passed highly classified information to the Soviet Union. By the early 1950s they had penetrated all the major institutions of British state security.

Highlights from this release: Kim Philby

Following the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean in 1951, Philby fell under suspicion and was summoned home from Washington for interviews with Dick White, the Chief of MI5 counter-intelligence. The transcripts can be found in KV 2/4723, and they show how Philby tried to deflect blame onto Burgess for alerting Maclean that he had been unmasked as a spy.

On 12 December 1951, Philby was interviewed by Helenus ‘Buster’ Milmo, a barrister and an MI5 Officer. The eighty nine page transcript in KV 2/4727 shows that it was a very exacting interrogation, a determined attempt to get Philby to confess his guilt as a spy for the Soviet Union. Philby did not concede this, but the transcript shows that he frequently had no answer to Milmo’s forensic lines of questioning.

In 1962 proof emerged that Philby was indeed a Soviet agent, and, in January 1963, an MI6 officer went out to Beirut to confront him. MI6 policy is not to name officers (and the officer’s name has been redacted in the MI5 files), but it is commonly known that the person who confronted Philby was his old friend, Nicholas Elliott.

KV 2/4737 contains the records generated by that encounter, including Philby’s confession statement, dated 11 January 1963 – a partial confession, covering 1932 to 1940. In the transcripts of conversations between the two men in Beirut, Philby claimed to have spied for the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946, but gave no meaningful explanation about why he allegedly desisted.

The transcripts reveal that Philby made a fleeting but significant admission, that he had passed on information to the Russians about Konstantin Volkov. A Soviet intelligence officer stationed in Turkey, Volkov had privately offered to defect to the UK – before he and his wife were taken by Soviet agents and executed in the Lubyanka in Moscow.

Highlights from this release: Anthony Blunt

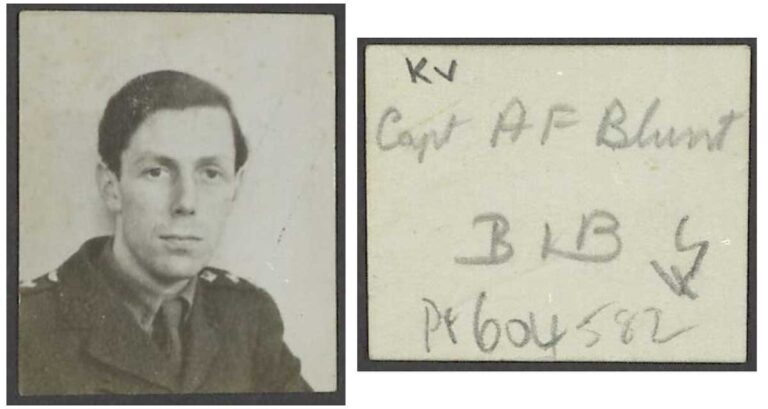

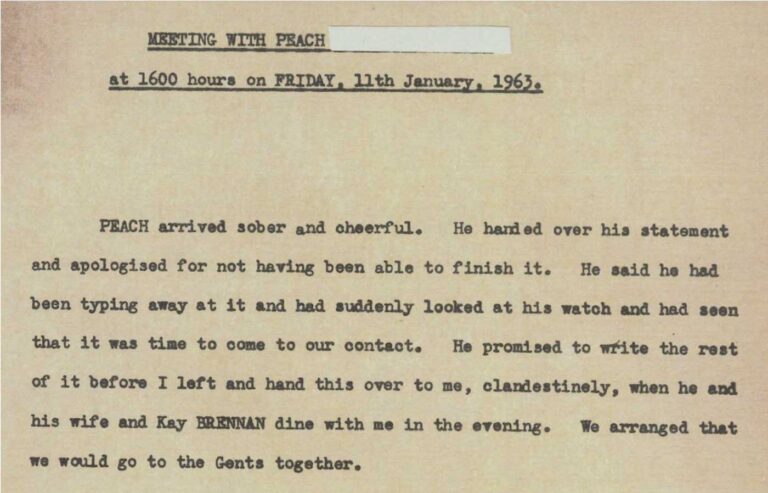

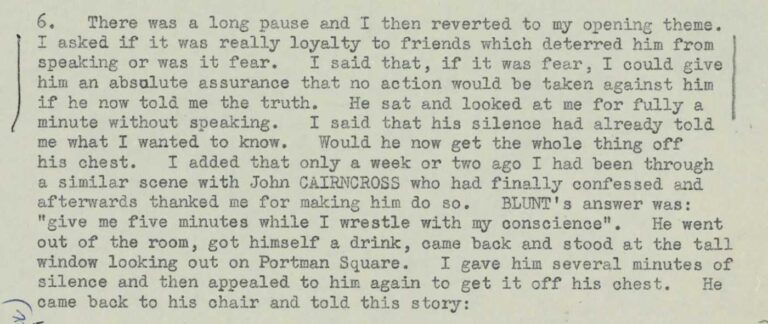

KV 2/4705 includes a riveting account of an interview with Anthony Blunt by MI5 Officer Arthur Martin, in Blunt’s flat above the Courtauld Institute on 23 April 1964, in which he finally confessed to having been a spy for the Soviet Union.

Although Blunt had been given an assurance that no action would be taken against him if he now told the truth, Martin was left with the impression that Blunt was still withholding certain information.

From 1945 onwards Blunt was appointed Surveyor of the King’s (and later the Queen’s) Pictures, responsible for the Royal Collection of Pictures. He held that position until 1972, and remained in an advisory capacity to the Royal Collection until 1978. As such, Blunt remained at the heart of the establishment for over 30 years. In KV 2/4721 we learn that in 1973 the Queen was told about his case.

Further highlights

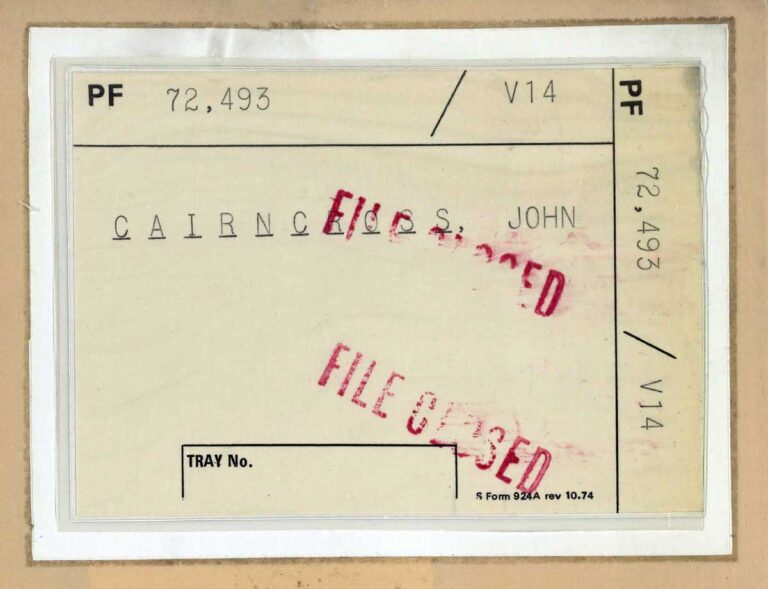

KV 2/4691 includes an account – again by Arthur Martin – of an interview with John Cairncross, which took place in Ohio on 16 February 1964. In the interview Cairncross admitted that he had been recruited by the Russian Intelligence Service (RIS) in 1936, soon after he joined the Foreign Office.

He goes on to talk about his first encounters with Maclean, Burgess and Philby, his work on decrypted messages at Bletchley Park and his career path in general. Very little material has been released about Cairncross before – 22 files concerning him are now made available in this release (as well as 22 files on Blunt and 21 files on Philby).

The release also includes files (KV 2/4744–4754) concerning Italian nuclear physicist Giuseppe Martelli, a nuclear physicist who was arrested under the Official Secrets Act in 1963, while in possession of espionage-related paraphernalia. He was suspected of working as an agent for the Russian Intelligence Service and was prosecuted but found not guilty.

There is also a file (KV 2/4673) concerning Dirk Bogarde, the famous actor and writer. Following up on information from a source, MI5 thought that he may have been approached by the Russian Intelligence Service. MI5 interviewed Bogarde in 1971 and established that there was no cause for suspicion.

In addition, the release contains some policy files in the series KV 4, including MI5’s liaison relationship with the FBI, 1949–55, and liaison between the Director General and the Prime Minister, 1963–68.

MI5: Official Secrets

The stories of the Cambridge Five, and others enhanced by these new releases, will feature in the forthcoming major exhibition at The National Archives, MI5: Official Secrets, which opens in the spring.

The exhibition will mark the first time MI5’s secret history is going on display to the public, featuring original case files, photographs and papers, alongside the actual equipment used by spies and spy-catchers over the Security Service’s 100-year history. And it’s free, so do plan to visit if you can!

You can also find links to further new spy-related articles on the exhibition webpage, including the story of Karl Muller and the fatal lemon, dating back to the early days of MI5 (around the First World War).

Talk about bad news for British Intelligence what with Philby, Blunt and the Queen but it’s hardly surprising given that even Ian Fleming didn’t know what a secret agent really was! Ian Fleming dubbed James Bond a “secret” agent yet simultaneously depicted 007 as an employee on MI6’s payroll. Given Ian Fleming’s background in British naval intelligence in World War 2, that contradictory classification of 007 was about as absurd as calling a Navy Seal a Coastguard as noted in this news article – https://theburlingtonfiles.org/news_2024.09.13.php. If only the Cambridge Five had been able to read Bill Fairclough’s fact based spy thriller, Beyond Enkription in TheBurlingtonFiles series, they may not have been caught!

Spying for an enemy is treason and should be punished as such

The file on Edward Wilding Playfair (a senior Treasury official), although he appears to have been innocent he was still awarded a knighthood and criticism of Treasury’s vetting of him.

Why continually use the ridiculous term “Russian” intelligence service when referring to the Soviet period of the Cold War? [it’s like the tabloid naming of the “Russian linesman” famous in the 1966 World Cup final when in fact he was from Azerbaijan, or referring to Stalin as Russian when he was Georgian!]

Dear Mike,

Thank you for your comment.

Russian Intelligence Service (RIS) is a term which is frequently used in the Security Service files. It is an umbrella term covering the intelligence services in Russia, both historically and in the present day. The terms ‘Russia’ and ‘Soviet Union’ tend to be used interchangeably in the files, and this is the case for many historians referring to Russia and/or the Soviet Union, in the period 1922-1991.

Are you letting us in on WW2 (or leading to) material on MALTA?

Dear Frederick,

Thank you for your comment.

We are unable to speculate about future transfers of records from the Security Service.

Can one hope for files from M16 to be released in future for historians?

Was there an M14 in the Cold Ear?

None of the Cambridge spies were ever prosecuted.

Thank you for your comment.

MI6 records are retained by that organisation. The intelligence and security services are exempt from the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act 2000.

To the author’s knowledge, there was not an MI4 in the Cold War. He thinks it was disbanded a short while after the end of the Second World War.

One issue is that spying often gets a romantic treatment. But Philby’s activities alone cost many lives. I hope that the exhibition etc is hard-edged, showing the worst aspects of state sponsored espionage as well as its benefits.

Where and how do we get to read these in full? Fascinating!

Dear Claire,

Thank you for your comment.

Anyone is free to visit The National Archives and see the records in our collection. This blog contains links to the files mentioned in our catalogue (such as this one), which explain the different ways each file is available.

You can also use our live chat or online form for help and advice on accessing our collection.

I have read KV 2/4723-43, which I hope is all the Philby files, though 4743 seemed out of chronological order.

I find it weird that Five should voluntarily release these files and yet about 10% of pages are totally redacted and huge numbers of names and and many near-entire pages. I was hoping to find references to my father, a close colleague, and friend, in Six but nothing. It is near certain he would be mentioned as he visited Philby in Dec 1950, even giving an ex-OSS friend the Philby’s as a ‘poste restante rather’ than the Embassy.

But the maddest redaction is that of Nick Elliott from the Beirut ‘interview’ when he had outed himself. In contrast the Czech services have released 99% of their Communist-era records unredacted. So much for our post Waldegrave Open government!

Is this true that none of the Cambridge spies were ever prosecuted and if so, why not?