71 years after the end of the Second World War the collective story of the millions of victims of Nazism and genocide is well known, but as survivors become fewer, first hand accounts are shifting from the spoken to the written word.

New files released today at The National Archives are the latest documentary evidence to shed new light on this history, in this case by offering a glimpse into how West Germany compensated – in monetary terms – British victims of Nazi persecution.

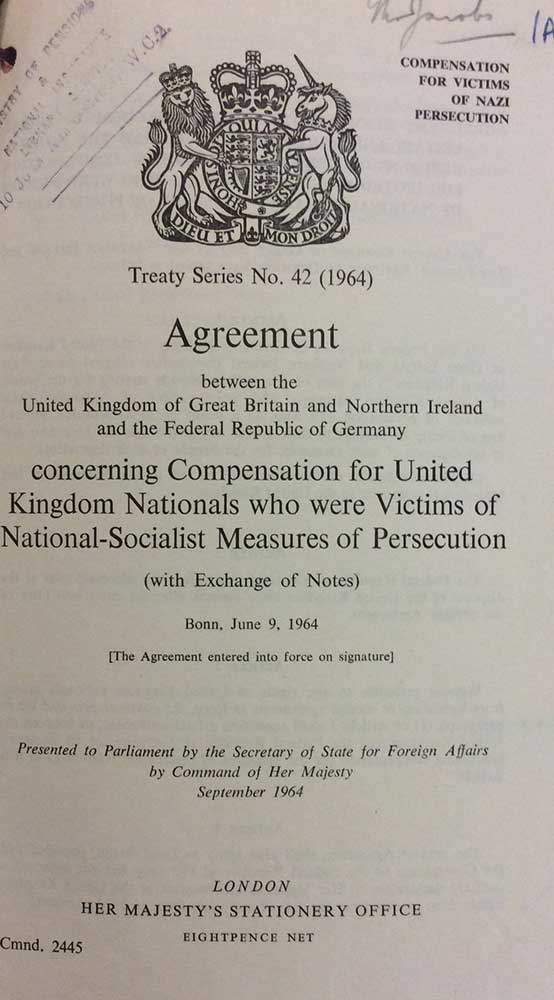

After a period of negotiation beginning in the mid-1950s, the West German state agreed in 1964 to provide the British government with £1 million to distribute as compensation among British victims of National Socialism. After making a call for applicants via newspapers, the radio and television, the Foreign Office received over 4,000 forms from individuals who claimed to have been victims of Nazi persecution.

However, by the end of the process the Foreign Office was only able to accept 1,015 of these claims; the reasons behind the refusal of the other 3,000 applicants rested largely on different definitions of the term ‘persecution’. In their attempt to reach and compensate with the limited funds available those who had suffered the most, the Foreign Office applied relatively narrow criteria of eligibility for what constituted persecution. Though there were exceptions throughout the process, this typically meant having been interred in a ‘concentration camp or comparable institution’ (PIN 76/3).

Compensation agreement (catalogue reference: PIN 76/3)

The case files from this process – of which the first tranche are released today – provide details of these claims for compensation made between 1964 and the closure of the scheme in March 1966.

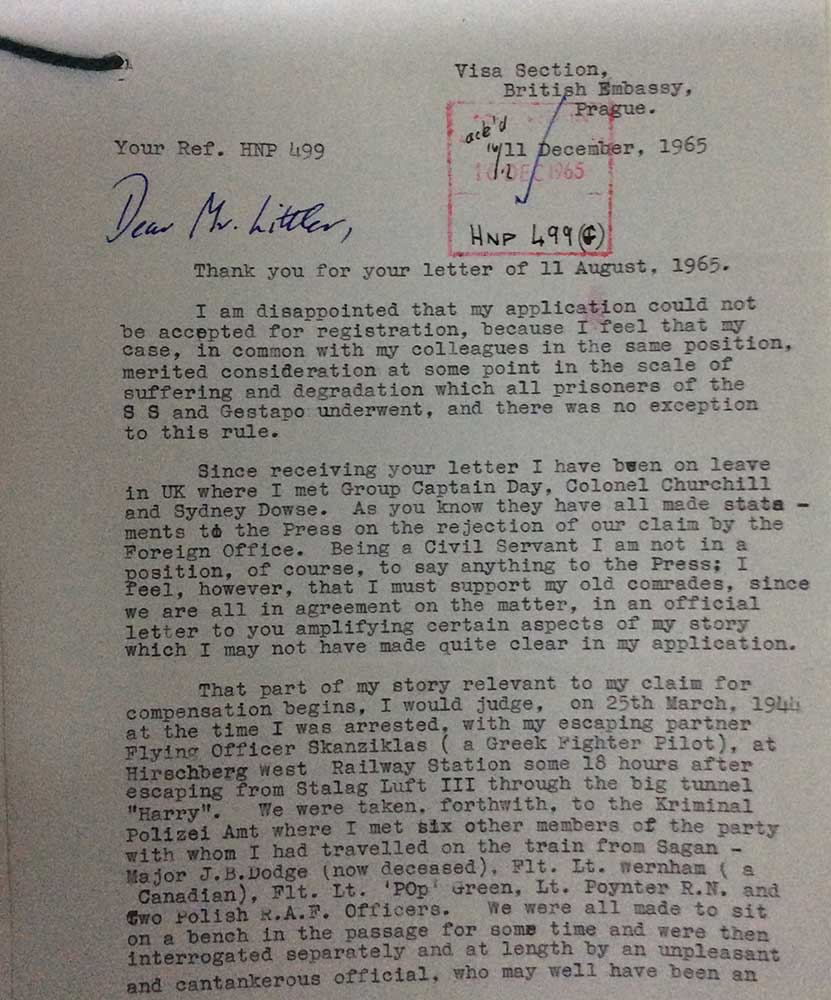

Many of these files contain first-hand accounts written by Jewish and non-Jewish victims that may otherwise have been forgotten. A number of names, however, will likely be familiar to some. One of these is Bertram Arthur ‘Jimmy’ James (FO 950/1327). James was an RAF Officer captured by the Germans in 1940 and held in various camps over the course of the next five years. It was from one of the camps, Stalag Luft III, that James, along with 75 other men, attempted the much-celebrated Great Escape. It was the getaway via the three secretly dug tunnels – Tom, Dick and Harry – that was immortalised by the 1963 film and this act of ingenuity has captured the British public’s imagination ever since. Of the 76 who escaped, 73 were recaptured. Over half of these men were executed, although James was one of those spared and sent instead to Sonderlager A at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

James’ application contains his lengthy account of what happened next and describes how he was ‘kept for 5 months in solitary confinement under harrowing mental and physical conditions, not knowing when [his] turn for the firing squad might be’.

Despite the harrowing details, his application was initially rejected by the Foreign Office because he was not ‘subjected to the now well-known inhuman and degrading treatment of a concentration camp proper’. The British press were so outraged by James’ treatment – as well as that of the 10 other Great Escapers who had had their claim refused – that a Parliamentary Enquiry eventually overturned the decision in 1967. A sum outside the allocated £1 million of £20,515 was divided equally amongst the 11 (FCO 64/59).

Letter from Bertram Arthur James (catalogue reference: FO 950/1327)

The Foreign Office’s requirement for an individual to have been confined to a concentration camp or comparable institution also caused tensions among Channel Islanders. As the only British soil occupied by Nazi forces during the war, they naturally produced a large number of applications to the scheme. Being interned in a civilian camp did not lead to compensation, as it was essentially legal under the rules of war; those who engaged in resistance efforts, however, often did not receive the same treatment. Many were transferred to Gestapo prisons and in some cases concentration camps.

One such example is Frank Hubert Tuck, whose file provides a fascinating insight into the kinds of small – albeit effective – acts of anti-Nazi resistance on the islands. Tuck was one of 17 police officers in Guernsey, arrested for pilfering German stores which he did ‘to sabotage the enemy’s [position all [they] could’. Tuck and his compatriots claimed to have been taken to various camps including a forced labour camp in Neuoffingen in 1942. He was later moved to the outskirts of Landsberg and finally Dachau concentration camp. He details in depth his treatment and that of others such as Police Sergeant Harper who was ‘beaten with a pick and shovel, kicked and trampled’. Also within his file is a claim for permanent medical disability, and the usual correspondence between the applicant and the Foreign Office. In spite of the Foreign Office criteria, Tuck was awarded the maximum payment of £4,000 for the ill-treatment he suffered. Efforts were also made to find and compensate his colleagues.

Naturally, of course, there are also a large number of files that relate to the particularly harrowing tales of Jewish suffering. One such story is that of Leon Greenman. Greenman was a Dutch-British Jewish man, who lived in the Netherlands with his wife and son. Along with the other Jewish inhabitants of his town, the Greenman family were rounded up and, despite protestations that they were British (and should be treated better than Jewish people of occupied counties) were treated as ‘Dutch Jews’. They were therefore sent to Auschwitz. His wife and young son met the same fate as millions of Jewish victims who passed through the gates of this infamous extermination camp; they were sent to the gas chambers on arrival. Leon Greenman, however, survived, and was part of the death march to Buchenwald, where he was later liberated. His personal account reveals the anguish he experienced at losing his family in Auschwitz, and the extent to which he wished to pursue justice against the Dutch officials who ignored his British citizenship and ultimately – he argued – led to the death of his family. Unfortunately, he was refused compensation on the grounds that he was eligible under the Dutch scheme. His account, of course, is only one of many. However, as first-hand oral testimony become rarer, examples of written, personal accounts of the Holocaust – such as this one- are increasingly valuable.

These documents offer not only a rare insight into the personal experiences of men and women who suffered at the hands of the Nazis, but also the conflicting needs and memories of the groups who sought compensation. Though the British government had predicted a flood of applications from people recently naturalised who sought refuge in Britain during or after the war, they also found those who had fought in British uniform or lived in outlying occupied lands expected their share of the compensation.

The policy files and now these personal accounts help tell how these differing demands were dealt with by the Foreign Office. They also act as reminder that, for those who experienced suffering at the hands of the Nazis, the effects and memory of this persecution lasted far beyond the end of the war.

It would be useful if TNA released a list of files of people whose files actually contains names of the victims, rather than that there name has been redacted from the files and description, it is like looking ‘for a needle in the haystack’ and one does wonder why the files in these cases have been released at all. Of course other departments like Treasury are likely to have the names in, in the days before data protection, and of course people may have died but the file may not say so, but an FOI request cannot be made since the names have been removed from the catalogue, one wonders what would happen if all files at TNA were treated so. Of course one would expect Treasury and the Inland Revenue to have a large input and incidentally the ‘West German state’ is of course the Federal Republic of Germany from its inception in 1954.

Dear David,

The value of these records, even without names associated with them, is unquestionable. Many researchers are not interested in the experience of specific individuals, but rather instead are interested in the overarching experience of Nazi occupied Europe, and particularly of those persecuted specifically under Hitler’s regime. As such, there’s no need to identify, and potentially embarrass, specific individuals. I think this is a very exciting record release indeed!

Dear Louise,

Thanks for the reply, I would suggest that not all of the files are going to be useful and of course a lot of such information has been made available to various organisations. I would add that, certainly in the case of FO 950/830 that the information left in has enabled me to discover who the claimant is and when they died. I am more interested in who the people were in the first place. The issue of embarrassment has never been a reason for closing and if it was files would never be released, e.g the comments by Oliver Letwin when he was a Special Adviser.

Thank you for this! This is an invaluable source for future research into this dark period of history!

[…] Find out more on our blog: How were British victims of Nazi persecution compensated? […]

Are there plans to release the documents relating to those who had to flee Germany before the start of the war? My mother was one of these and I recall her getting a compensation payment (and, I think, a second payment) in the ’60s.

Hi David,

This agreement won’t have covered those, like your mother, who had to flee Germany before the war. Without knowing under which scheme she was awarded compensation, I couldn’t advise on where to look.

Soryr I can’t be of more help!

My father was a POW who was also held in a concentration camp. I remember that he did receive some compensation during the 60’s. If I were able to supply details of his army number and proof of his death would it be possible to gain access to his claim?

Hi Anthony,

Where the names of the claimants have been released, you can search Discovery by name within the series FO 950. Where the names have been withheld (for data protection purposes), you can search using key words such as ‘Nazi persecution’ or ‘name withheld’ within the series FO 950 on Discovery. II hope this helps! The files, however, are original so cannot be viewed online.

I hope this helps.

first the british mandate, and now this!

are the c=documents available online?

Hi Stefanie,

These files are original documents so cannot be viewed online. You can, of course, view them in the reading rooms here in Kew, or pay for a copy of a relevant document to be sent.

I hope this helps.

[…] Find out more: How were British victims of Nazi persecution compensated? […]

I am searching for archive information regarding my Father Squadron Leader Stanley Booker RAF who was a captured by the SS in Paris 1944 and interned in Buchenwald concentration camp. He applied for compensation under the scheme.

Hi Pat,

Unfortunately we’re unable to help with family history requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

You are probably better off asking the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, given the fact that they decided not to release a number of names and Booker is not on the Discovery catalogue for these records.

The person who lead the campaign for the Sachsenhausen claimants (the 11) was Airey Neave MP (of Colditz Castle fame) and with the help of the Parliamentary Commissioner of Administration and that the Foreign Office’s original settlement of claims was c onsidered to be perhaps based on incomplete data, see T 312/772 and 1885. It is also interesting that the Chief Secretary to the Treasury didn’t want to get involved but to leave it the Foreign Secretary and that the UK was the last of the Western governments to agree a deal with the Federal Republic of Germany despite the UK having an Agreement with Japan in 1950.

Hi, i’d like to know if you can give me some orientation… A friend of mine, a 92 years old lady, is living right now un Spain. She is from Russia, she was confined in a guetto for two years, then escaped, traveled to France, changed her name and last name, then moved to Venezuela where lived most of her life and now, she moved to Spain a few months ago. Anyway, I would like to know if there is a way she can get any compensation or if there is any organization here in Spain where she (or her family) can go to ask for information.

Hi Sid,

Unfortunately we won’t be able to help with your query on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Hi,

My late Father was a victim of Nazi persecution on grounds of his political activities against the Nazi regime. He was German but had to flee his country before the outbreak of War to avoid further imprisonment/execution. Prior to this he spent 2 years in prison because of his beliefs and associated activities against the Nazi regime.

Despite returning to Germany after the war, he subsequently returned to Britain due to the intolerable poverty, and discrimination, the latter which remained evident amongst some of the Nazis which still existed and at that time remained free.

It seems unjust that he was compelled to relinquish his German citizenship in favour of being naturalised to enable him to remain in Britain. Dual Nationality did not exist at that time.

I have applied for German citizenship by decent but given my late Father was given British citizenship 2 years before my birth it will be difficult for me to be awarded this by “Decent” despite my Father being granted lifelong compensation for the inhuman treatment he suffered and his deprivation of liberty.It makes no sense that he met the criteria for compensation but then on this technicality no mitigating circumstances may be made for his circumstances?

Seems like although the grounds exist for me as his Daughter to receive German citizenship by decent, the decision to relinquish German citizenship due to this being imposed upon makes no difference.There was of course no option to seek dual nationality at that time.

[…] necessary given the British government’s refusal to award Leon any financial assistance from the German-funded compensation scheme that was available to Holocaust […]

[…] necessary given the British government’s refusal to award Leon any financial assistance from the German-funded compensation scheme that was available to Holocaust […]

[…] That was much higher than the average success rate of British claims – only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful. […]

[…] That was much higher than the average success rate of British claims – only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful. […]

[…] That was much higher than the average success rate of British claims – only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful. […]

[…] That was much higher than the average success rate of British claims – only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful. […]

[…] That was much higher than the average success rate of British claims – only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful. […]

[…] That was much higher than the average success rate of British claims – only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful. […]

[…] That was much higher than the average success rate of British claims – only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful. […]

[…] That was much higher than the average success rate of British claims – only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful. […]

[…] That was a lot increased than the common success fee of British claims – only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful. […]

[…] That was much higher than the average success rate of British claims – only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful. […]

My father escaped to England with what was left of some of the Polish Army. All of his remaining family in Poland were slaughtered in Concentration Camps. My father died I 1973 and I believe he may have got a little compensation from Germany but if so not much. I am wondering how it is that Germany did not pay substantial compensation for the murder of my would be family and for the loss of all properties belonging to them. Being “top dog” in Europe do they feel that they still might have a moral duty to do so. Regards Simon.

My father fled Nazi persecution in Austria to the UK. After the start of the war he was interned by the UK govt in Australia for 2 years and his possessions were confiscated. He was one of a few survivors after his boat was torpedoed in the Atlantic on his return. He died in 1990 but is survived by my mother/his widow, who cared for him in our family home until his death. As far as I know my father received no compensation from the UK gov. My mother 87 has dementia and is in need of care – is there any govt program or govt assistance that could assist with payment of her care.

Sincerely Andrea