Chris Heather writes: In this blog entry one of our volunteers, Carol Kellas, highlights the role of magistrates in dealing with disturbances across England in 1808, as recorded in the Home Office papers.

The papers in record series HO 42 (Domestic Correspondence, George III) include instances of serious violence in various parts of England in 1808 which highlight the role of magistrates in dealing with serious crime. Unlike magistrates today, who have the details of criminal cases placed before them by the police and Crown Prosecution Service, magistrates in 1808 worked very much on their own. They might be able to call on the help of a village constable in routine criminal cases but for anything serious they had to investigate themselves, justify their actions to the Home Office, and call on the military to assist the civil powers when mobs gathered and violence was threatened. They also had to commit accused persons for trial and take sureties to ensure the attendance of witnesses. In some ways their role feels closer to the European investigating judge role than that of a magistrate today.

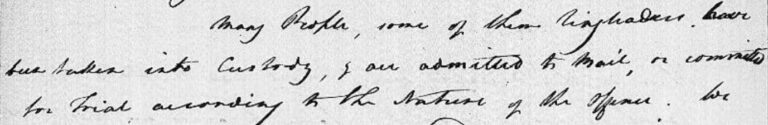

In the summer of 1808 magistrates had to deal with several instances of serious communal violence arising from strikes in the north of England. The costs of essential foods such as flour and oatmeal had been rising due to the War in Europe but wages had not risen in proportion. In May a Manchester magistrate, Mr Farringdon, reported a crowd of around 2,000 people assembling two days running in support of higher wages for weavers. He called on the military for support, and on the first day the crowd was dispersed without trouble. But on the second day one demonstrator was killed (after attacking a dragoon with brickbats) and another was seriously injured, with several others taken into custody. On the third day the weavers waited for an answer from the manufacturers to their request for a rise in wages. They asked the magistrates to intercede for them, but they said that they could not act on behalf of a mob, but would consider any action they could take following representations made in a peaceful manner. A notice was posted reminding people that the punishment for riot was death.

Further disturbances involved an assembly of 3 to 4,000 people who were encouraged by the Irish weavers who would not disperse until the military were called in. Two of the Irish weavers were shot dead in the act of throwing stones at the soldiers.

According to Charles Prescot and John Philips, magistrates from Stockport, the trouble stemmed from the fact that a Bill for fixing the wages of the cotton weavers was thrown out in the House of Commons, resulting in considerable unrest in the local area. Large bodies of men were assembling with the aim of forcing the manufacturers to raise their wages. They were also preventing others from working, and their families were starving due to their very low wages. Although this had been known for six months, nothing had been done and they were now in such a miserable situation that they no longer cared if they perished. They knew that the law was against them but said that ‘extreme want’ was the cause. The merchants and manufacturers set up a committee to consider the claims of the weavers, and magistrates reported that some immediate relief had been provided to the families.

The expected meeting of the manufacturers did take place and seemed to have stilled the disposition to riot for the moment. Mr Farringdon’s understanding was that a pay increase would be made in certain cases. This, however, was not, in his view, a guarantee of full, or any, employment and might not be enough. He recommended that a stronger force be stationed in Manchester. He subsequently committed seven men to Lancaster for trial on capital offences.

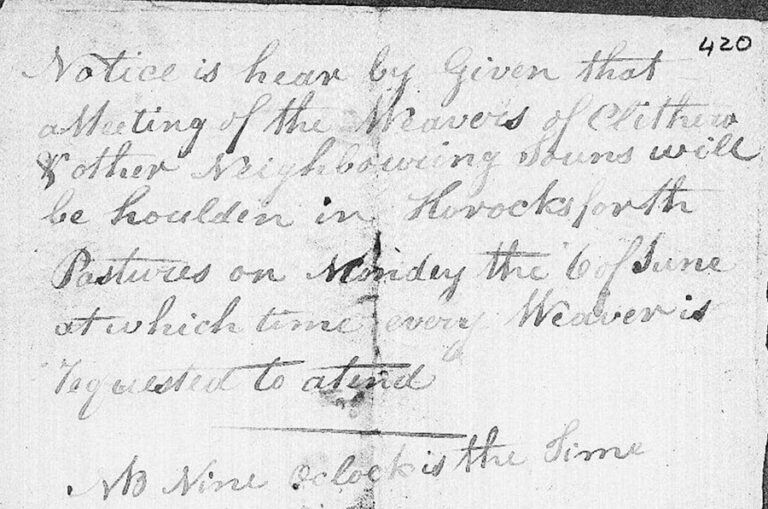

Meanwhile things were not going well in Rochdale, Lancashire. In June magistrates Thomas Drake and John Entwistle reported some serious breaches of public order. A mob, several thousand strong, broke into the private houses of weavers and took away their shuttles and other work implements. The police office was attacked with large stones thrown through the windows, putting the magistrates at risk. Later that evening the prison was broken into and burned down. During the night a furious mob extorted money by threatening to burn down gentlemen’s houses, factories and mills. The magistrates called on the military for help, and eventually a half troop of cavalry arrived from Manchester, together with the Halifax Volunteers, and order was restored. The magistrates requested the Minister of War to station two troops of cavalry at Rochdale permanently, without which they doubted whether it would be possible to carry on the work of the magistracy. They asked for the proclamation of a pardon for anyone giving evidence leading to conviction of the rioters.

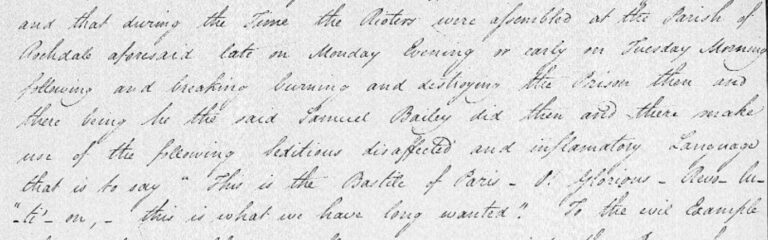

Mr Entwistle subsequently reported the committal to the Lancaster Assizes of Samuel Bayley, bookkeeper, on a charge of sedition. He was bound to attend on a recognisance of £1,000 with two sureties in the sum of £300 each. The Constable and two witnesses were each bound in the sum of £100 to attend and prosecute. Information was laid by John Turner of Rochdale, a surgeon, and Thomas Kershaw, a merchant, who said that Bayley was present at the burning of the prison and was heard to make remarks such as: ‘This is the Bastille of Paris’ and ‘This is what we have long wanted.’

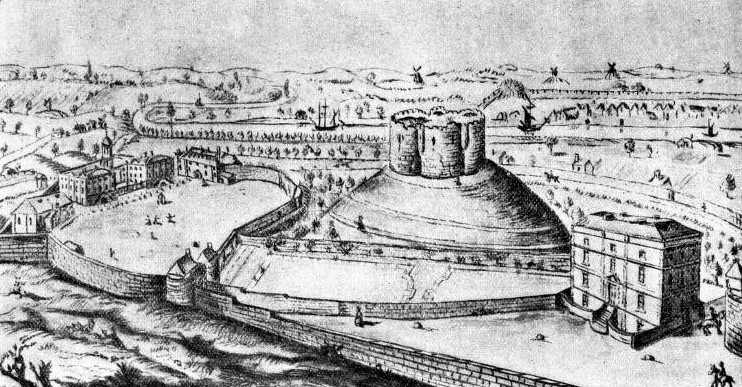

Meanwhile, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the Reverend Doctor Collins was busy committing Richard Latham, Richard Pye and Samuel Smalley to York Castle to stand trial for felony. They were part of a mob of about 100 men which forced its way into the house of Thomas Taylor, a farmer of Bradford, demanding to search the house for food. They ransacked his chests and demanded bread and cheese. Collins committed a further four men and two women for trial, one of the ringleaders being Ellen Isherwood, ‘an audacious and dangerous character’. Collins was assisted by a small company of dragoons under Cornet Warbrick and by the Craven Legion who escorted the accused to York.

Summer violence took a different form in the countryside where political dissatisfaction led to the burning of hayricks in Nottingham, Oxford and Denbigh and the usual rewards were offered for information leading to a conviction of those responsible.

Sometimes the violence was personal. In June, Edwin Newgill JP wrote from Hornby, near North Allerton, Yorkshire, about the case of a poor industrious man, Michael Metcalfe, whose sheep had been killed by a malicious person during the night of 1 May. One ewe and several lambs had been killed and only one lamb escaped through a hedge. The local farmers and gentlemen offered a reward of £100 for information leading to a conviction. And Thomas Russell, Mayor of Hereford, was clearly frightened by an anonymous letter put into the Hereford Post Office which threatened to burn his house down for allowing the bakers to cheat on the weight of their loaves.

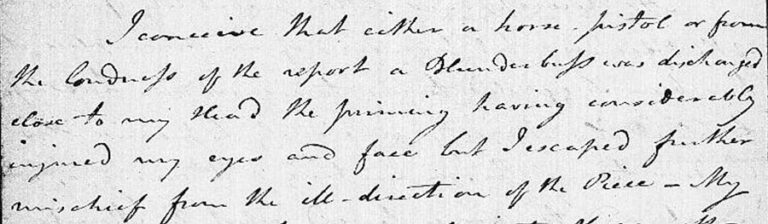

Being a magistrate could also make you a target. In January, John Jones wrote from Woolley, near Bradford, Wiltshire to report an attempt on his life, which he attributed to his having been active as a magistrate in 1802 and dealing with violent outrages against the introduction of machines in the woollen manufacturing industry. He was returning on horseback from his factory one evening when a horse pistol or blunderbuss was discharged close to his head, injuring his eyes and face.

Jones thought that there were seven or eight men involved. His horse took off, thus taking him out of range of any further attempt. The local manufacturers were proposing to offer a reward of £1,000 for information leading to conviction of those involved and Jones asked that a pardon be promised, and published in the Gazette, for any accomplice who provided information leading to such a conviction. He also asked for Bow Street officers to help with the investigation.

Not surprisingly customs officers were often targeted. In November (HO 42/95 f. 728-736) the Excise Office reported an incident at Lawton in Cheshire. Customs officers discovered that a quantity of salt had been taken from a warehouse without the necessary duty having been paid. They arrested one person but were then set upon by 20 men variously armed. A gun was fired at one officer leaving him with small shot in his head, neck, shoulder and arm. Permission was sought to offer a reward for information leading to a conviction and for the offer of a pardon for any accomplice who came forward. Randle Wilbraham JP committed one man to prison for the attack but had to report that he had not been able to get the man to confess.

In January a Mr Richmond wrote about a violent attack on William Blackett, a watchman stationed at one of His Majesty’s warehouses for seized spirits in Deal, Kent. He was attacked and dangerously wounded by five or six men who were lurking with a view to plundering the warehouse. The Customs House Board offered a reward of £100 for information leading to a conviction and asked that a pardon be offered and published in the Gazette for any accomplice who gave evidence leading to a conviction.

In London mob violence, especially near the docks, followed more predictable lines. The Whitechapel magistrates Williams and Davies reported an affray near the docks in East Smithfield between some American and Portuguese sailors arising from a drunken dispute about women. Several men were wounded by blows from bludgeons and one American was stabbed and had to be taken to hospital. Three Portuguese sailors were committed for further examination. The next night a large crowd gathered at the same place and some windows were broken. However, the crowd dispersed when the magistrates appeared with the officers. The Whitehall Volunteers commanded by Colonel Hardy stood by to give assistance to the civil power but were not needed.

We do not know whether John Jones was successful in his request for the help of a Bow Street officer to investigate events in Wiltshire, but it is worth noting that, in April, the Magistrates of Horncastle, Lincolnshire, thanked the then Home Secretary, Lord Hawkesbury, for agreeing to send down a Bow Street officer to help investigate what they were sure was a murder. They got a rather testy response. Lord Hawkesbury said that there were so many requests of this kind from around the kingdom that the magistrates should be reminded that the expense of this assistance must be borne by them.

Over time the question of who was to bear the costs of the investigation and prosecution of crime came increasingly to the fore as magistrates asked why they and their local communities should have to be responsible for this. Increasingly central Government was asked to help, with magistrates making increasingly forceful representations to the Home Office, including hints that prosecutions might have to be dropped unless there was help with funding. The whole question of police assistance in the actual investigation of crime was another story.

Very interesting – a vivid picture of unrest and the response of those in authority.