Sixty-five years ago, on the afternoon of 16 March 1953, Britain welcomed an unlikely visitor to these shores – the communist dictator of Yugoslavia: Josip Broz Tito. It was the first time a communist leader had visited a Western country and marked the start of friendly relations between both countries. It was also the first time Tito had left the relative safety of Yugoslavia after falling out dramatically with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.

Emerging through the particularly thick fog at Westminster Pier aboard a London Port Authority barge, Tito had sailed to Greenwich aboard his yacht Galeb (Seagull) before heading up the Thames in the smaller vessel which could sail under London’s bridges, cleared of pedestrians and traffic due to security concerns. The first person to shake Tito’s hand as he disembarked was the Duke of Edinburgh, before being greeted by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden.

Marshal Tito by artist Marc Stone (Ref: INF 3/82)

This scene would have been inconceivable in the immediate years following the Second World War. Despite being allies in the battle against the Nazis, Yugoslavia’s subsequent violent actions towards the West went far further than the Soviet Union dared. Two American planes were shot down over Yugoslavia in 1946, while British-backed troops were under attack from rebels supported by Tito in the Greek Civil War. The Yugoslavs had also laid claim to the Adriatic port of Trieste and surrounding area, rivalling similar claims from NATO member Italy.

Stalin expected Tito follow his orders and his patience was finally exhausted in June 1948, with Yugoslavia expelled from the Communist Information Bureau (Cominform). The Kremlin hoped to scare Tito into falling in line with the eastern European satellite states but the tactic failed. Instead, fearing dangerous isolation, Tito turned to the West and soon found receptive ears to his appeals for assistance.

British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin came up with a policy to ‘keep Tito afloat’ and a change of government in London did not alter this approach. Eden, Bevin’s Conservative successor, accepted an invitation to visit Yugoslavia in September 1952, primarily viewing the trip as an opportunity to enjoy some late summer sun.[ref] FO 371/102179 Eden note to Churchill, 14 July 1952. [/ref] According to protocol, Eden mentioned that perhaps Tito would one day like to visit Britain. No one seriously expected the dictator to accept so readily and propose a date for the following spring.

The possibility of Tito visiting in March 1953 posed plenty of difficulties. Top of the list was the fact that Queen Elizabeth II had not yet been crowned, with the Coronation being planned for June.

Notwithstanding the fact Tito had overthrown the monarchy in his own country, there was a long list of foreign leaders expecting to be invited to Britain ahead of the communist dictator of Yugoslavia. It took personal intervention from Churchill to ensure that Tito would come on an ‘official’ but not a ‘state’ visit. Churchill focused on the positive aspects of the visit in a Cold War Europe where the battle lines were still being drawn. A friendly Yugoslavia would be strategically beneficial to Britain with major interests in the Mediterranean and east of the Suez Canal. A friendly Tito would also be an embarrassment to Stalin and show the satellite states that there was an alternative to Moscow rule.

White Lodge in Richmond Park

Royal involvement in the visit was not thought to be necessary by some at the Foreign Office; however, when Buckingham Palace was approached, a message came back that the Duke of Edinburgh was actually keen to meet Tito and would like to greet him on his arrival. Things moved quickly and it was soon agreed that Tito would be given an official reception at Buckingham Palace and even dine with the royals.

Hundreds of letters protesting against the visit were sent to MPs across the country but the Foreign Office hoped increased contact with the Yugoslav leaders would lead to more liberal policies and individual freedoms being introduced in that country over time, predicting: ‘Once the “window on the West” has been opened, it can never be shut.’ [ref] PREM 11/578 FO report to Churchill, March 1953. [/ref]

Home Secretary David Maxwell-Fyfe thought that Tito would stay at the Yugoslav Embassy on Kensington Gore during his five-day stay – as would be the norm for an official visit of a foreign leader. However, the Yugoslavs hoped for something a little grander and Churchill again was happy to oblige if it meant Tito would come. The Duke of Wellington’s Apsely House was considered but in the end White Lodge, in Richmond Park, was chosen. On hearing the news, a relieved Duke of Wellington wrote to Churchill, admitting: ‘I am glad my patriotism has not been put to the test.’[ref] PREM 11/578 Wellington letter to Colville, 17 Feb 1953. [/ref]

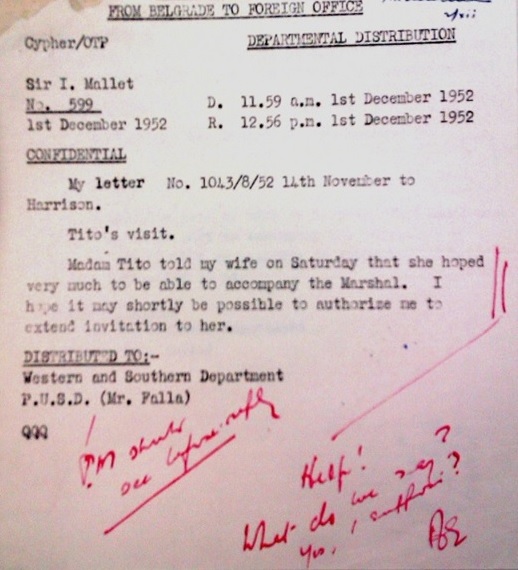

The presence of Tito’s wife Jovanka Broz in London, especially at Buckingham Palace, would certainly have pushed things far closer to appearing to be a State Visit. A telegram from the British Ambassador in Belgrade reporting that she was expecting an invitation caused concern in Whitehall. A panicked Eden wrote at the bottom of the telegram in red ink: ‘Help! What do we say? Yes, I suppose?’[ref] FO 371/102184 Eden minute, Belgrade telegram to FO, 1 December 1952. [/ref] However, after a lengthy delay, Madame Broz seems to have read between the lines, and announced that she would be unable to make the trip after all.

Anthony Eden’s ‘Help’ in red ink (Ref: FO 371/102184)

The schedule of Tito’s visit records trips to the British Museum, the Tower of London, Windsor Castle, Hampton Court Palace, and a night at the ballet watching from the Royal Opera House Royal Box. At RAF Duxford for an air show on a miserable grey morning, a shocked Tito witnessed two Gloster Meteor pilots being killed when their aircraft clipped wings.

On 17 March, he met Churchill at 10 Downing Street, where Tito insisted that any Soviet attack on Yugoslavia must lead to world war. Britain, France and the United States had previously considered such an action as being a regional affair. But in London, Tito found that Churchill agreed that Soviet military aggression towards Yugoslavia, directly or by proxy, would lead to the West intervening fully on Belgrade’s behalf. [ref] PREM 11/577 Report on meeting at 10 Downing Street, 17 March 1953. [/ref] Churchill’s assessment was later accepted in Paris and Washington. Buoyed by this apparent support, Tito became fully committed to seeing what he could gain from bilateral relationships around the world, rather than committing to the West, establishing the Non-Aligned Movement in 1956.

The reference to the FCO 371 is incorrect, it is FO 371, the Foreign Office did not become the FCO until 1968 and neither did the records. The comment about a ‘”regional war” involving Yugoslavia is interesting given what happened to Yugoslavia after Tito died.

Hi David,

Thanks for pointing that out – I have amended the text accordingly.

Best regards,

Liz.

My father ( 92 not out ) served as a lieutenant on one of the 2 Yugoslav destroyers that escorted Tito’s vessel the Galub as far as Malta for his trip to the Queens coronation. From Malta British ships accompanied Tito to England.

I seem to recall that sometime in the early 50s Marshal Tito being driven from Hendon aerodrome to London. This was when I worked in Colindale and I was cycling home when an escorted car passed me.

Is this correct?