This is a story of how new and fascinating information about our collections can sometimes come seemingly out of the blue. It began with an email from the grandson of photographer Francis William Cobb, whose photographs have been sitting within The National Archives’ collection since 1975.

The Reverend F W Cobb was Rector of Eastwood, Nottinghamshire, from 1907 to 1917. He was a photography enthusiast and took photographs of his parish and parishioners, most of whom worked in the coal mining industry. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Rev. Cobb gave lantern slide lectures on the history of coal mining illustrated by his photographs. Those lantern slides are the only records we hold of his photographs and they can be found in record series COAL 13.

A new enquiry

Earlier this year I was contacted by the grandson of Rev. F W Cobb, who wished to discuss the records held at The National Archives. He was in possession of a large number of his grandfather’s photographs – glass negatives as well as prints. He held some of the glass negatives from which the lantern slides in COAL 13 were originally produced, as well as a large number of other photographs, some depicting coal mining scenes and others showing industrial scenes (particularly Stanton Ironworks), buildings, churches, street scenes, children, birds and more. The quality of the photographs was amazing and they made an impressive collection. They were also all in the original boxes in which they had been placed by Rev. Cobb and some were labelled with his notes.

We discussed Rev. Cobb and his work as a photographer, and this initial discussion spurred me on to want to find out more about the records we already hold. The only information we seemed to have readily available about the slides in COAL 13 was the following catalogue description:

This series contains a set of slides which were nearly all taken at the collieries of the former Barber Walker and Co (mostly at Moorgreen and Brinsley) around Eastwood, Nottinghamshire between 1907 and 1914. The slides were taken by the Rev F W Cobb, Rector of Eastwood, Nottinghamshire from 1907 to 1917. The set is entitled ‘From Pit to Fireplace’ and would appear to have been used to illustrate a talk on the history of coal mining.

The original glass lantern slides are delicate and can only be produced for readers in our invigilation room at The National Archives. However, the slides have been digitised and are available to view in our image library.

From Pit to Fireplace

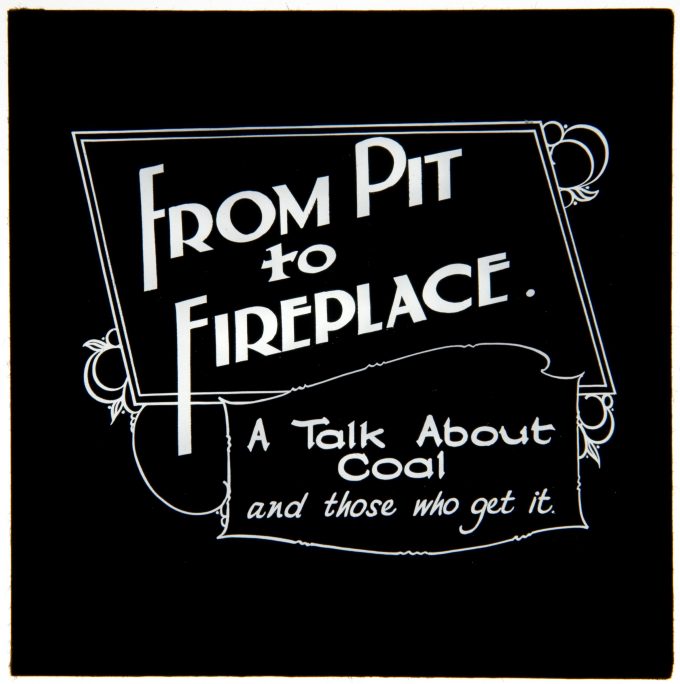

One can see clearly from the set of images that they were created to illustrate a talk. The first image is the title slide, which reads ‘From Pit to Fireplace: A talk about coal and those who get it’.

Title slide: From Pit to Fireplace. Catalogue ref: COAL 13/1

The subsequent 114 slides depict various subjects, including mine shafts and facilities, pit ponies and equipment, miners at work and at rest, miners with their families, and miners playing cricket. The set also includes slides which seem to have been intended to illustrate the more historical side of the talk. These include maps, illustrations, diagrams and portraits of prominent figures. Most of the photographs were taken in Nottinghamshire and in particular at the Brinsley Colliery near Eastwood, and others show pits which may be located in Walsall or Lichfield[ref]Colin Osman, Arts Council of Great Britain, ‘The British Worker: Photographs of Working Life 1839-1939’ (1981)[/ref].

- Church choir at pithead, 1913. Catalogue ref: COAL 13/84

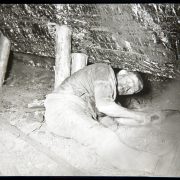

- Hand holing, November 1913. Catalogue ref: COAL 13/28

- Beginnings of a new shaft, 1913. Catalogue ref: COAL 13/18

- Bringing Daddy home, 1907-1914. Catalogue ref: COAL 13/94

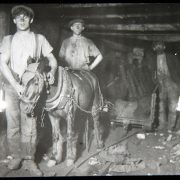

- Little Tick favourite pit pony, 1913. Catalogue ref: COAL 13/51

- Miner at rest, March 1912. Catalogue ref: COAL 13/95

The glass lantern slides

I ordered the glass lantern slides to review their arrangement and condition. I was surprised to discover them in their original boxes as stored and labelled by Rev. Cobb. Looking at the original slides exactly as they were prepared by the photographer and lecturer gives such important context to the record, which is lost when looking only at the digitised versions. This demonstrates the importance, particularly when researching visual materials, of seeing them in their original material format.

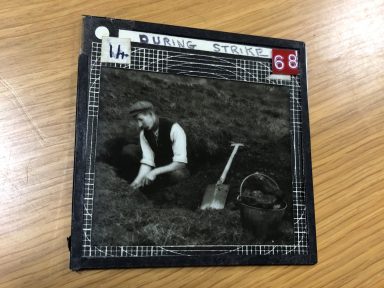

- “During Strike”. Catalogue ref: COAL 13/68

- Rev. Cobb’s original glass lantern slides. Catalogue ref: COAL 13

In his own words

After discussing the collection with Rev. Cobb’s grandson, it became clear that the materials he held did not consist only of photographs but also of written records collected by his grandfather. These included press cuttings and articles which Rev. Cobb had published at the time. His grandson was kind enough to share these articles with me, which give vital context to the images held in COAL 13.

The reverend’s interest in the work and lives of his parishioners led him to take his camera into the pits to gather images and experiences. Rev. Cobb wrote articles about his experiences for various publications including ‘The Kodak Magazine’ and ‘The New Photographer’. His photographs were also published in newspapers including the ‘Daily Herald’ and the ‘Nottingham Guardian’.

In an article published in the ‘Church Monthly’ in April 1933 titled ‘A Rector and his Camera in Coal Mine: Coal-Getting in a Strange Place’, Rev. Cobb wrote:

‘Nine years in a mining parish with the majority of my men returning from their shifts literally “as black as coal,” has given me a keen interest in that wonderful mineral and all that pertains to it. In building up a series of photographs of the collier’s life and work for lantern slide and lecture purposes, my camera often accompanied me down the pits of my colliery parish of Eastwood, Notts. There, time and again, I had plenty of interesting photographic experiences, and the hard work (and heat!) attached to put photography in a dim light and very cramped space made one all the more glad when the resulting negatives gave satisfactory pictures'[ref]F W Cobb, ‘A Rector and his Camera in Coal Mine: Coal-Getting in a Strange Place’, ‘Church Monthly’ (April 1933), press cutting from F W Cobb Private Collection[/ref].

Rev. Cobb was not afraid to immerse himself fully into the coal-mining industry, in order to understand better the experiences of his parishioners and produce more interesting photographs. In his articles, he gave detailed and dramatic descriptions of the men, mine shafts and equipment to complement his photographs. In an article for the ‘New Photographer’, published on 31 May 1926, he wrote:

‘We are sorely tempted to stop en route and get a picture of the pit ponies drawing their heavy loads of coal “trams,” the stables where they are snugly bedded down when their shifts are over, the main roads with their carefully propped roofs and gleaming rails, and the various blasting operations which are continually in progress. As we get further away from the shaft we find the roof getting lower and at last a final turn brings us right up to the coal face. Opposite us is a four-foot seam, a solid wall of glistening coal, with every one of its ten thousand facets catching the light from our safety lamps and reflecting it with a diamond’s sparkle'[ref]F W Cobb, ‘New Photographer’ (31 May 1926), p. 175, press cutting from F W Cobb Private Collection[/ref].

‘A heavy toll of brave men’s lives’

It is evident from reading these articles that Rev. Cobb was concerned with the welfare of the coal miners and wished to educate the general public about the nature of the industry and the conditions of those who worked in it. In an ‘Overseas’ article titled ‘The Underworld of a Coal Mine’, he wrote:

‘Here is the coal-getter at work. Like Nelson’s sailors when they were in action, he prefers freedom of limb and access of air to his hot body to the covering even of his singlet. The miner’s is a hard life, and danger ever lurks at his elbow. Though happily not common, we know well enough the horrors of a big colliery explosion. In Great Britain about a million men work in the mines, and the yearly average of fatal accidents is over a thousand, while one in every seven worker meets with some minor casualty. So as we watch our friend at work we shall do well to remember that much as we value the coal he wins for us, it is ours only at the cost of a heavy toll of brave men’s lives and limbs'[ref]F W Cobb, ‘The Underworld of a Coal Mine’, ‘Overseas’, p. 51, press cutting from F W Cobb Private Collection[/ref].

Within the collection of cuttings, there is one short piece giving an account of one of the lantern slide lectures give by Rev. Cobb in a village hall in 1933. The author described how ‘the lecturer hoped that some knowledge of the miner’s toil, so often fraught with danger, would give those present a more intelligent sympathy with him’. The author also described how, at the end of Rev. Cobb’s lecture, he showed the audience an example of a miner’s safety lamp invented by Sir Humphrey Davy[ref]‘Elsenham’, press cutting from F W Cobb Private Collection[/ref].

Cricketing miners

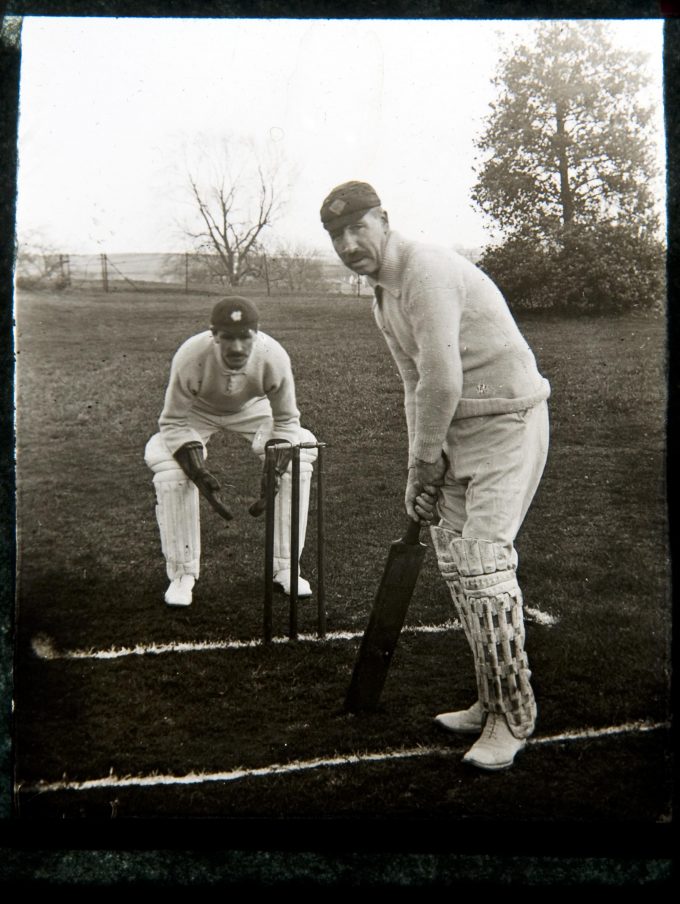

The additional material has also given some fascinating context to a few of the photographs in COAL 13 which were, up until now, a bit of a mystery. These include a photograph of three men posing in their cricket whites and also two men playing cricket. The articles published by Rev. Cobb reveal that the game of cricket was a particular focus for the miners of Eastwood. He wrote in an article for ‘The Cricketer’ in 1923:

‘As I got to know my men, I soon found what a front-rank place cricket held in the traditions of that mining centre. The colliery management, too, knew this well and gave it the most practical encouragement possible by providing an excellent cricket ground which formed a nursery, where much local talent was developed. So it came to pass that as many as twenty-seven professionals have taken their places as coaches and groundsmen in the last ten years, and in one year alone – 1920 – the number was fourteen’[ref]F W Cobb, ‘Coals and Cricket’, ‘The Cricketer’ (1923), press cutting from F W Cobb Private Collection[/ref].

Cricketing miners, 1912. Catalogue ref: COAL 13/104

The three men above, posing first in their cricket whites and then in their working clothes are known as The Webster brothers. These men were described by Rev. Cobb as ‘local celebrities in the cricket world’ in his article in ‘The Cricketer’. In the same article, he wrote of his parish that ‘here we have a considerable body of men who are as adept with a pick and shovel in the winter months as they are proficient with the bat and ball when the brighter days come round'[ref]F W Cobb, ‘Coals and Cricket’, ‘The Cricketer’ (1923), press cutting from F W Cobb Private Collection[/ref].

Cricketing miner Tom Oates, 1912. Catalogue ref: COAL 13/102

One particular subject is Tom Oates (pictured above), who was a friend of the photographer and wicket keeper in the Notts County XI. In the years after these photographs were taken, Oates took to umpiring, standing in Test matches between 1928 and 1930[ref]http://history.trentbridge.co.uk/players/thomas-william-oates.html (accessed 9 December 2019)[/ref]. In an article in ‘The Pathfinder’, Rev. Cobb wrote:

‘Some of my miner friends stand out strongly in memory. One of these was Tom Oates, now an international cricket umpire, and in my Eastwood days a miner in the winter, wicket keeper for the Notts County XI in the summer, and a chorister in my church choir'[ref]F W Cobb, ‘The Wonderful Underworld of a Coal-mine: How the Coal Miner Lives and Works’, ‘The Pathfinder’, p. 123, press cutting from F W Cobb Private Collection[/ref].

The journey to The National Archives

The photographs taken by F W Cobb in record series COAL 13 were not originally public records. The photographer was not acting in any official government capacity when he took the photographs, rather he was an amateur photography enthusiast who gave public lectures. It is surprising then that these photographs are held at The National Archives at all, since most records held here are those of central government departments and law courts. To find out how the Cobb photographs made their way to the archive, I consulted the relevant accession file in PRO 57/2461.

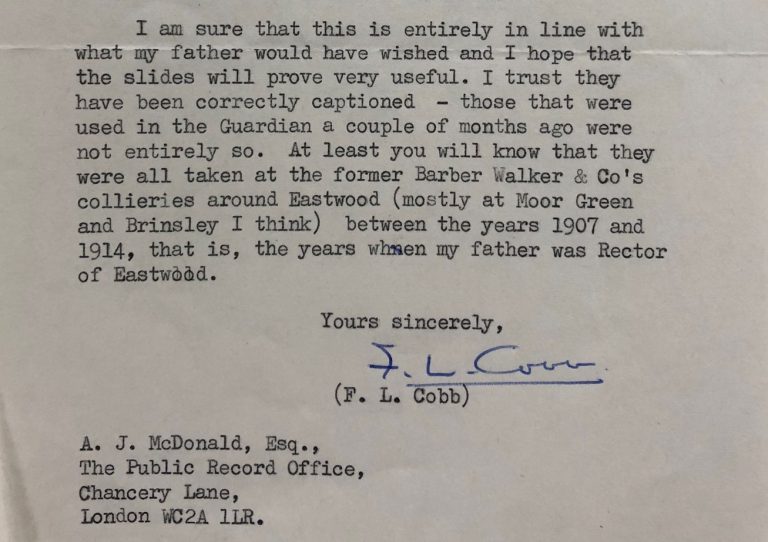

The file reveals that the 115 glass lantern slides now in COAL 13 were given to the National Coal Board in 1966 by Rev. Cobb’s son, F L Cobb. Subsequently, in 1972, the National Coal Board wished to deposit the slides in the Public Record Office for safekeeping and asked permission of F L Cobb who duly granted it, saying:

‘Yes, by all means send my father’s slides to the Public Record Office. I had no idea that they preserved things of this sort; I thought they were solely concerned with State and other historic documents. I am sure this is right if it means that they will then be accessible to a much wider circle of students, researchers and others – and will be preserved under the best conditions'[ref]Public Record Office: Accessions of Records, Registered Files (Case Files), PRO 57/2461[/ref].

Further correspondence within the Public Record Office and between F L Cobb and A J MacDonald shows consideration of how the slides would be stored, catalogued and captioned correctly, in order to make them as accessible and useful to archive users as possible.

Letter from F L Cobb to A J MacDonald of the Public Record Office, 31 December 1972. Catalogue ref: PRO 57/2461

In 2003, the Public Record Office merged with the Historical Manuscripts Commission to form The National Archives and the Cobb photographs have been held here at our building in Kew ever since. This particular kind of journey of a record from private hands to The National Archives is fairly unusual. The National Archives does not accept donations of records from private sources and so, had it not been for the involvement of the National Coal Board, the Cobb photographs would never have been deposited here.

An enriched story

Looking at the original accession records of the Public Record Office can help to give us a sense of the intentions of those who deposited the records here. In this case, it is positive to read that the two most important issues for F W Cobb’s son were the safe and successful preservation of the photographs and their accessibility to a wide range of people. Now, thanks to Rev. Cobb’s collection of press cuttings kindly shared with us by his family, we have discovered much more contextual information about the photographs, opening up more opportunities to promote the records to wider audiences.

If anyone wishes to view the Cobb Photographs, they can do so on our image library. The original glass lantern slides can also be viewed in our invigilation room here at The National Archives in Kew.