In March this year, the British Film Institute issued a DVD compilation of films by some of Britain’s women documentary makers. The collection is called ‘The Camera is ours’ and one of the films featured is ‘Children of the Ruins’ by Jill Craigie.

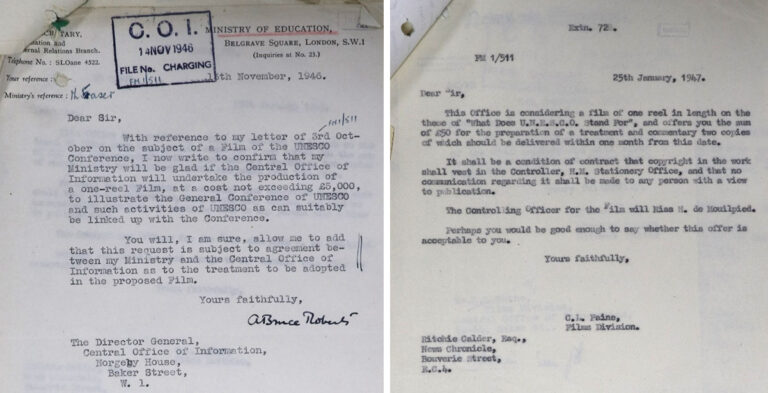

Craigie was a screenwriter and director, working mostly in the 1940s and 50s, and was married to Michael Foot who led the Labour party from 1980-83. Her film was commissioned by the Department of Education in 1946 through the government’s communications agency, the Central Office of Information.

The National Archives has the film production file for ‘Children of the Ruins’ (INF 6/393) and correspondence in the file shows that the aim of the film was to ‘illustrate the General Conference of UNESCO’ which took place between 19 November and 10 December 1946, and to answer the question, ‘What does UNESCO stand for?’

At the time the film was commissioned, UNESCO was a newly formed organisation. The acronym stands for United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation and it continues to operate today.

According to its own website,

‘UNESCO develops educational tools to help people live as global citizens free of hate and intolerance. UNESCO works to ensure that every child and every citizen has access to quality education. By promoting cultural heritage and the equal dignity of all cultures, UNESCO strengthens the bonds between nations. UNESCO fosters scientific programmes and policies as platforms for development and co-operation. UNESCO stands up for freedom of expression, as a fundamental right and a key condition for democracy and development. As a laboratory of ideas, UNESCO helps countries to adopt international standards and manages programmes that foster the free flow of ideas and the exchange of knowledge.’

www.unesco.org/en/brief (accessed 11 June 2022)

The idea of fostering cultural, scientific and educational co-operation and exchange to encourage peace between nations wasn’t new. In 1922 the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (ICIC) was formed as an advisory body to the League of Nations to ‘promote international exchange between scientists, researchers, teachers, artists and intellectuals’ (see footnote 1). However, the ICIC and the wider ambitions of the League of Nations proved insufficient to prevent the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

But the belief in the benefits of strong educational programmes as a way to sustain peace did not disappear. Still in the midst of the war, allied countries formed the Conference of Allied Ministers of Education (CAME). Each country sent its Education Minister to London in 1942 to share ideas around how to re-build education systems once the war was over (footnote 2).

This in turn inspired a plan for a permanent body to continue to develop and support educational programmes after the war, and towards the end of 1945, London hosted the United Nations Conference for the establishment of an educational and cultural organisation (ECO/CONF). It was here that the Constitution of UNESCO was signed by 37 countries, and a year later, the first UNESCO General Conference was held in Paris between 19 November and 10 December 1946 (footnote 3).

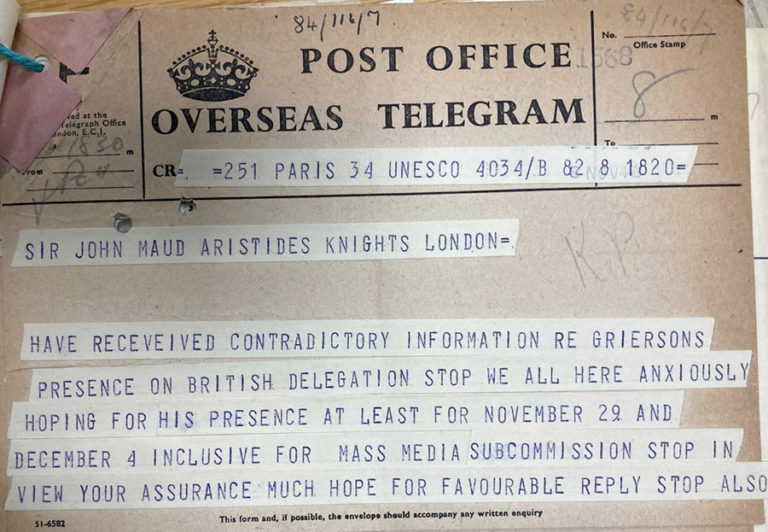

The National Archives has a file from the Ministry of Education containing details of the UK delegation to the Paris conference. The provisional list of UK delegates included the British novelist, J B Priestley, and pioneering documentary makers John Grierson, Paul Rotha and Basil Wright (footnote 4).

There seems to have been some concern over whether Grierson would attend, and the file includes a rather panicked telegram asking for confirmation that he would be present for the Mass Media Sub-commission.

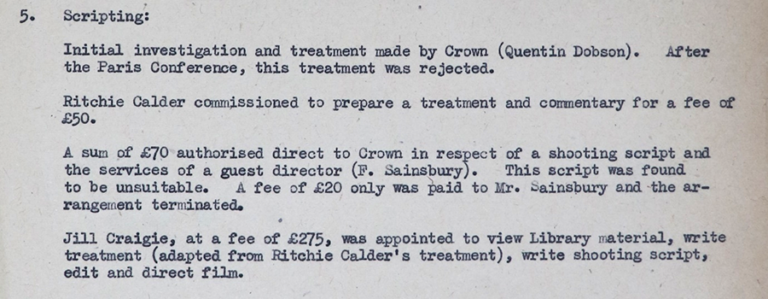

The Central Office of Information’s decision to commission Jill Craigie to make a film to promote the newly founded UNESCO was made only shortly before its 1946 Paris conference. The task faced by Craigie in making ‘Children of the Ruins’ was not an easy one – and this is borne out by the fact that three other directors had already had their treatments and shooting scripts rejected (footnote 5).

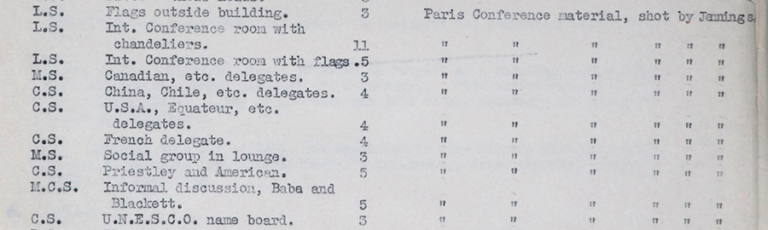

Papers in the film production file show that Craigie made her film by piecing together segments from film library sources such as British and German newsreels, War Office footage and other COI films such as Humphrey Jennings’ ‘A Defeated People’ (1946). Alongside this Craigie used footage of refugees commissioned from French company Caravelle, and film of the 1946 Paris UNESCO conference shot by Humphrey Jennings for the Crown Film Unit.

The footage used by Craigie depicts, in all its horror, the terrible effects of war on children. The film appeals to the audience on an emotional level and urges them to consider the necessity of the work planned by UNESCO. But getting the message across to cinema audiences in a short 10-minute film was not a simple task. People went to the cinema looking for an escape from the realities of post-war Britain, and it’s safe to assume they’d had enough of government messages interfering with their precious leisure time.

Indeed, as the script shows, Craigie injected some of this world-weary scepticism into the narration, with the male narrator (Cecil Trowner) being interrupted by Craigie herself challenging him with remarks like ‘What, another committee? What’s it all going to cost?’

But Craigie’s film explained that children across the world had been left without access to education and often without parents. The world needed to unite to address the needs of the next generation so that they in turn could build productive and happy lives. Rebuilding nations destroyed by war was not just about the physical infrastructure of roads, bridges and buildings, but about providing the mental and emotional infrastructure of future generations through education. As the last few lines of Craigie’s script says:

‘But if we have a scrap of humanity in us, can we blind ourselves to the plight of these children? Can we blind ourselves to this sort of thing? Difficult to feel for other people when they are so far away, but our neighbours matter, and if by now we haven’t learnt that, we haven’t learnt anything.’

Footnotes

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Committee_on_Intellectual_Cooperation ((accessed 15 June 2022).

- Conference of Allied Ministers of Education (CAME). Catalogue ref: ED 121/545.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UNESCO#Origins (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Meeting of UK delegation following 1946 Conference: 21 Jan 1947. Catalogue ref: ED 157/378.

- Summary of film on page headed ‘Children of the Ruins’ dated 12 December 1947. Catalogue ref: INF 6/393.

It talks of partition without explanation. Which ? Europe? Germany? India? Ireland ? China ? Still not clear what this is about, exçept references to the need for UNESCO.

Intrigued but not astonished to note that Jill Craigie worked from an initial treatment and commentary by Ritchie Calder. Having been taken from his desk at the Daily Herald early in the war to lend his expertise to wartime efforts in information and disinformation, Calder had both propaganda experience and sincere political convictions. Does Ritchie Calder’s text also exist? I would very much like to read it.

Really interesting material. My father was involved with IUCN in post war era and attended a conference in 1949 at Lake Placid that I believe was UNESCO. Anyway, so interested to learn more about female documentary makers of period.

Thanks for your comment Tim. The production file for Children of the Ruins doesn’t include Ritchie Calder’s original treatment unfortunately – but there is a separate file relating to a COI film from 1972 about Calder himself https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C4302645

Thank you for your comment Francesca – I can recommend the DVD ‘The Camera is Ours’ if you’re interested in female documentary makers from that period.