To walk through Chertsey, a medieval market town on the outskirts of London, you might not be aware that you’re walking through a site that was once at the centre of a religious powerhouse, with landholdings spread across much of medieval Surrey. Subtle hints in the landscape – a curiously shaped set of ditches near the cricket pitch, a small stretch of ruined wall among the trees, or the outline of an old gateway among the bricks elsewhere – are the only remaining signs of Chertsey Abbey, a once-proud medieval monastic community which stood until the 16th century.

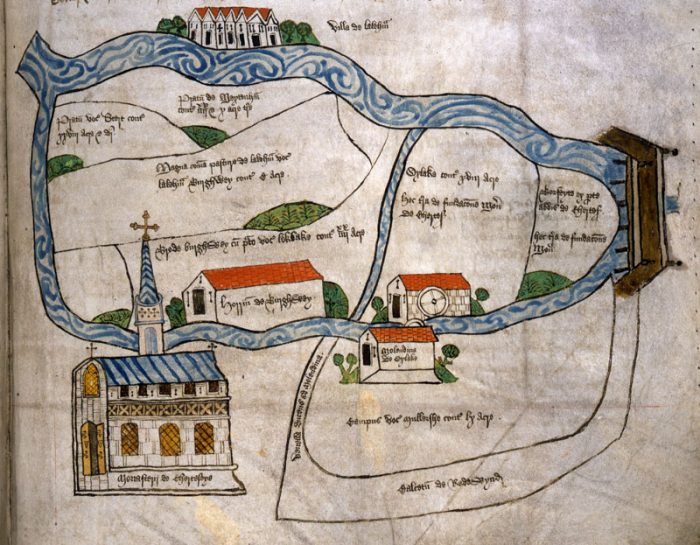

E 164/25 – Chertsey Abbey and lands, as depicted in the abbey’s Cartulary

At The National Archives we hold in our collections thousands of records relating to medieval monastic houses, many of which came into crown hands during the Dissolution of the Monasteries including Chertsey. Some of them are currently on display in an exhibition at Chertsey Museum – Chertsey Abbey: reimagined. I want to highlight in this blog some of these important documents, and the local stories they tell.

The abbey was founded in the seventh century, and by the time of the Norman Conquest had accumulated significant landholdings, which were recorded in the Great Domesday survey of 1086.

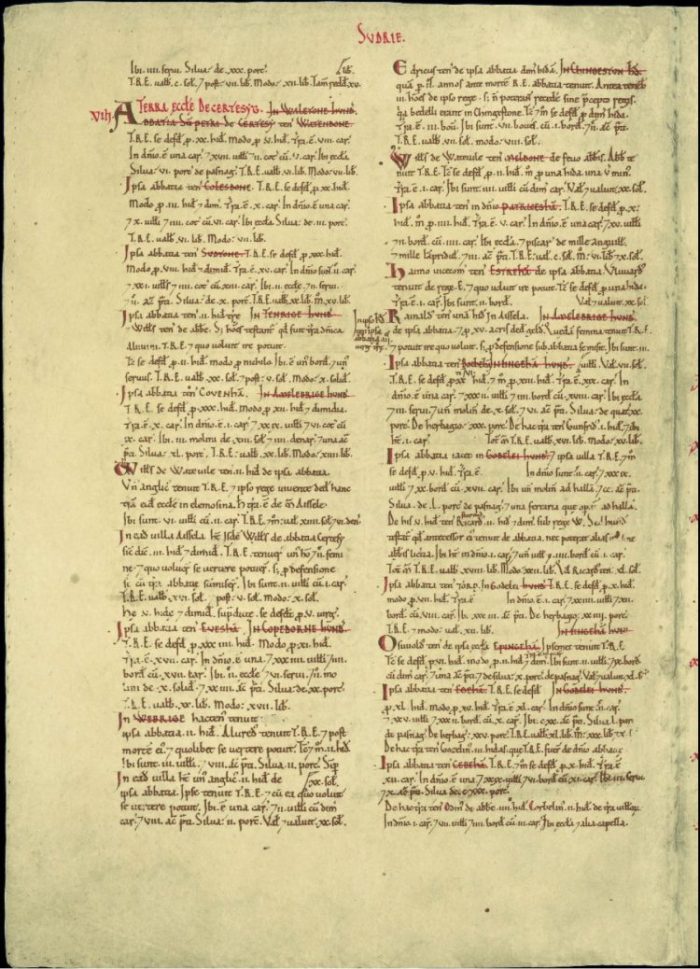

E 31/2/1/944 – Great Domesday entry for Chertsey Abbey, 1086. This image shows some of the abbey’s landholdings of Chertsey Abbey in Coulsdon, Sutton, Cobham, Esher, Epsom, Weybridge, Streatham, Chertsey itself, Egham, Chobham and Thorpe

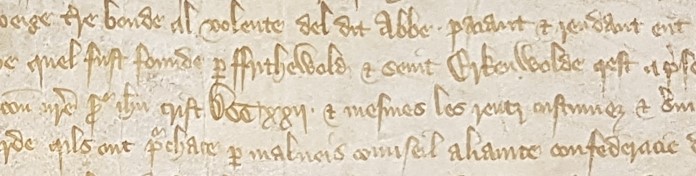

The abbey’s position as a landholder meant they often had strained relationships with local communities. This petition from John de Usk, Abbot of Chertsey, to the King and Parliament complained that the abbey’s tenants in Chobham, Frimley, Thorpe and Egham had refused to give the abbey their services and rents, as they had been established since the foundation of the Abbey. When his officials tried to force the issue, they were

‘resisted and menaced with staves and other weapons’

while the tenants threatened to burn down the abbey and kill the monks. The petition also shows a sense of historical thinking, as the abbot claims that Chertsey Abbey had been

‘founded by Frithewold and St Erkenwold in the year AD 722.’[ref] However, the Chertsey Cartulary held by the British Library contains an earlier date of 666AD[/ref]

SC 8/103/5106 – Petition from John de Usk, Abbot of Chertsey, to the King and Parliament, 1377-8. This section shows the alleged details of the Abbey’s foundation

This petition was one of many issued by landowners around the country in 1377-8, in reaction to tenants banding together and refusing their labour, and claiming that they were not bound under the provisions made in the Domesday survey. Many were able to receive exemplifications (official copies) of Domesday to push their claim, but in the Parliament of October 1377, they were judged to be in rebellion. The strikes were quashed, but the sparks of rebellion would fuel a much large uprising – the ‘Peasants’ Revolt’ – in 1381.

A similar petition (SC 8/103/5107) brought the abbey in conflict over the repair of the road between Egham and Staines (now the Causeway), giving another hint that relationships between abbey and the local community were not always positive!

One of our finest (in my opinion at least) medieval manuscripts is the abbey’s 15th-century cartulary[ref]Cartularies were volumes of copied texts concerning the lands, grants and privileges of religious institutions. The Chertsey cartulary in our collection is one of four extant cartularies for the abbey.[/ref]. The cartulary shows the abbey’s wealth and significant landholdings. On one occasion, the abbey’s landholdings were depicted visually, in a coloured drawing showing the fields between the abbey (shown) and the nearby village of Laleham (as seen at the start of this blog). This gives a rare insight into what the now-lost abbey would have looked like in its prime, although there are also depictions recorded on wax seals.

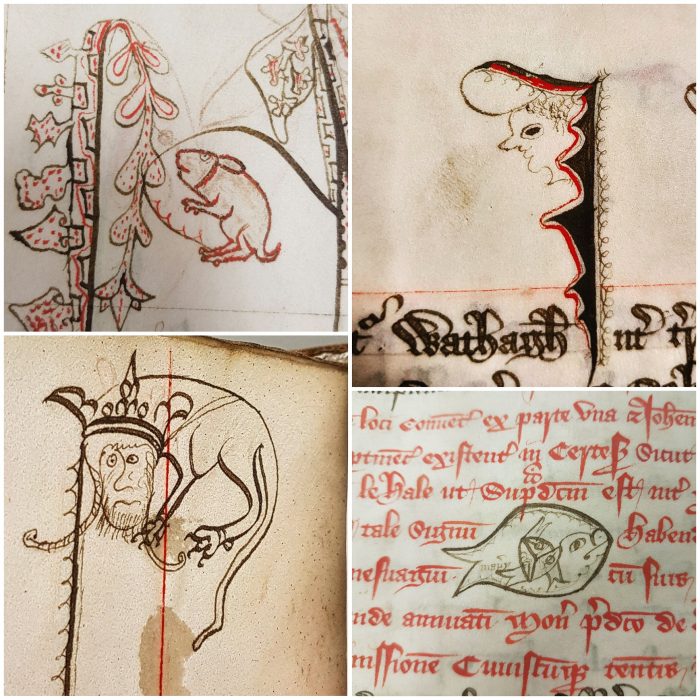

The cartulary also gives a personal side to one of the scribes involved in its production displays, who occasionally snuck in doodles in the margins including an aquatic creature in which he has inserted his own name ‘Manery (or Manory)’ (bottom right).

E 164/25 – Assorted doodles of scribe Manery, in the Chertsey Abbey Cartulary

The abbey reached perhaps its highest point in the 15th century when, after his death in the Tower of London, the body of Henry VI was taken to Chertsey. The abbey became a major pilgrimage site for those visiting the tomb of the late king. In 1484, his body was transferred to St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, where it remains to this day (despite a number of disputes around the matter).

The start of the abbey’s downfall began in 1535, along with many other religious houses around the country. The ‘Compendium Compertorum’ was the result of a large-scale inspection of religious foundations around the country[ref]Inspections of individual houses had been common throughout the medieval period, but these were usually conducted by the local bishop. After the Act of Supremacy of 1534, these powers reverted to the king and his nominated inspector (in this case Thomas Cromwell), who commissioned visitors to travel the length and breadth of the country to report back.[/ref].

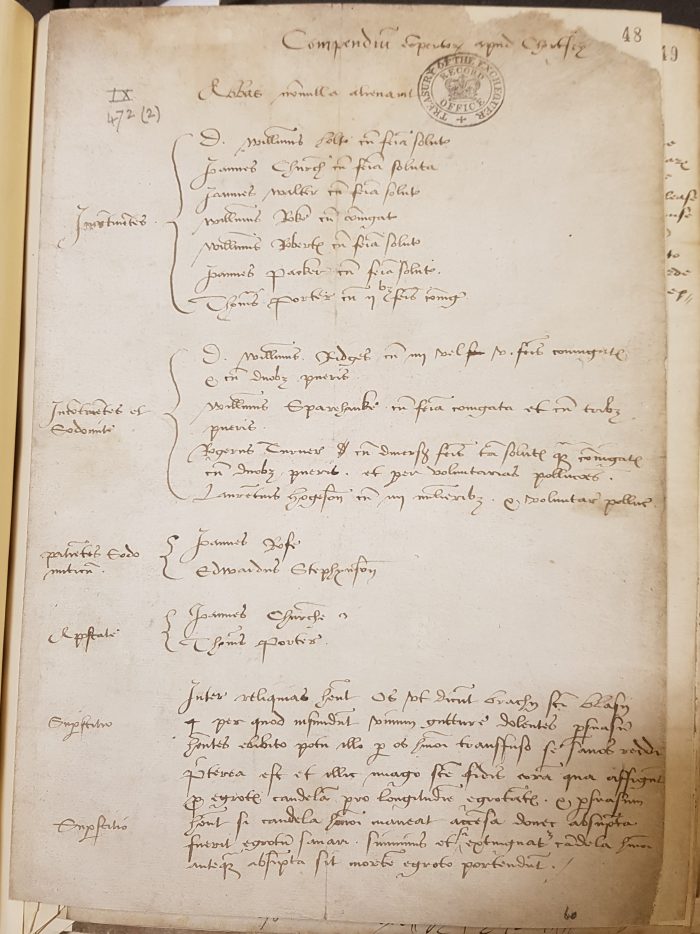

SP 1/97 ff. 47-8 – The ‘Compendium Compertorum’, 1535

It is difficult to judge how accurate the reports of the Compendium are, as they may have been used as an excuse for the subsequent dissolution of the monasteries (and the seizure of the immense wealth of the religious houses). Visitations of religious houses also allowed monks to air their own personal disputes, grudges and gossip, whether justified or not.

The report takes aim at ‘superstition’, a common theme throughout these documents, focused on the use of religious relics by churchmen and women. At Chertsey two relics were prominent:

‘Amongst the relics they have, as they say, the arm bone of St. Blasius, through which they give wine in cases of illness; there is also an image of St. Faith, before which they place a candle on behalf of sick persons, and hold that if the candle remain lighted till it is consumed, the sick person will recover, but if it goes out he will die.’

Sexual misdeeds were also a common theme in these documents, although the veracity of these claims are particularly difficult to verify. At Chertsey, it was reported that seven monks were ‘incontinent’ (acting outside of their vows of chastity) with women, while four were accused of ‘incontinence and sodomy’, with women, boys, and by ‘voluntary pollutions’. Two further monks were apostates (they had renounced their status as monks).

The account also claims that the abbot (John Cowdrey) had ‘alienated some things’. Such claims were reinforced in a letter from the monks sent to Thomas Cromwell later that year complaining that he continued to try and sell the abbey’s possessions. They claim that since the visitation:

‘he has sold wood and is bargaining away Chouceam (Chobham) Park…he has conveyed away the plate …[and] whereas the Abbot states in his letter that the portership has been given away, which you requested, it has not been granted under the Convent Seal.’

This letter is particularly important, as it lists some of the aggrieved canons, who signed the letter themselves[ref]The names include John Chyrche, William Roke, John Mylyster, John Walter, Ralph Wachatte and Thomas Potter.[/ref].

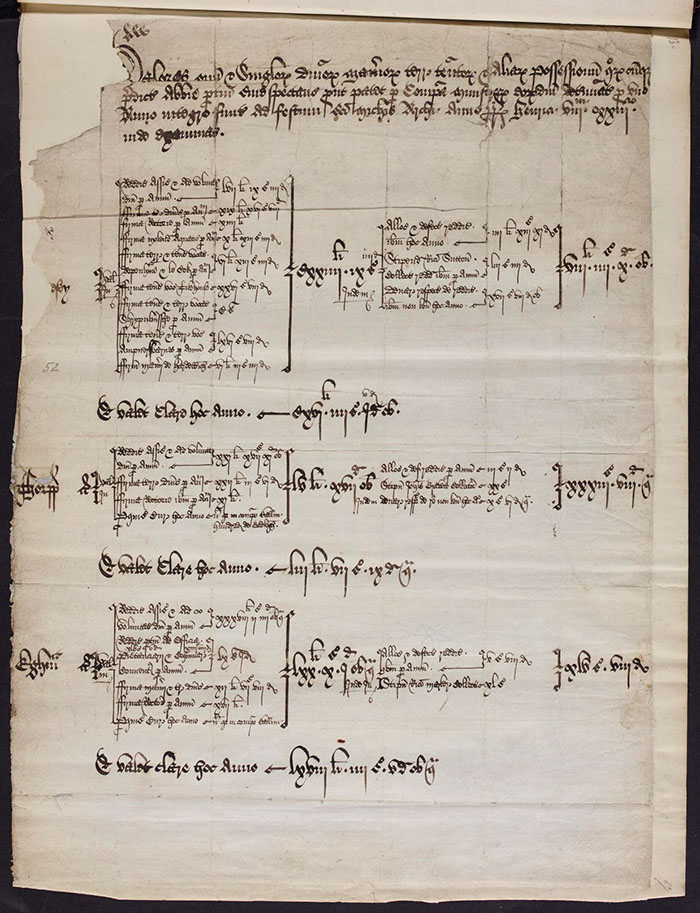

The document shown below records money coming in to the abbey from its estates, as well as some of the abbey’s outgoings including wine, fuel and expenses for travelling to London. Attached to this working financial account, however, is a draft valuation (or valor) of the abbey’s lands and estates.

SC 6/HENVIII/3456 – Abbot’s account of Chertsey Abbey, including a valuation, 1531-33. Entries of the valuation of lands in Chertsey, Thorpe and Egham shown here

Not long after this financial account was compiled, the Valor Ecclesiasticus, the greatest survey of ecclesiastical property since 1291, was undertaken across the country. The survey valued taxes paid to the Crown from ecclesiastical property and income previously paid to the Pope. It is likely in this case that the abbot’s own financial accounts were used as evidence in assessing the abbey’s wealth while the commissioners were preparing their findings. The final valuation of the abbey and its estates came to £659 15s. 8¾d.

Chertsey Abbey surrendered to the Crown in July 1537 in anticipation that their house would be re-founded at Bisham Abbey near Marlow (a former house of Augustine Canons, which had itself been dissolved in July 1537). The new foundation was to pray for Henry VIII and his late wife Jane Seymour, and was to be a prestigious institution. The abbot, John Cowdrey, was even permitted to wear the mitre of a bishop. The abbey community moved to their new site in December 1537, but Cowdrey continued in his former ways. A visit from one of Cromwell’s administrators, Richard Layton, in 1538 recorded Cowdrey as ‘a very simple man… [while the monks were] of small learning and less discretion’.[ref]SP 1/133 f. 170 – Letter from Richard Layton, priest, to Thomas Cromwell, June 1538[/ref]

The abbey had been left impoverished by Cowdrey’s machinations and because none of the abbey’s endowments had materialised. There was very little plate and household stuff in the abbey, no grain, few vestments, and Layton was forced to borrow beds from the town for himself and his companion. He claimed that:

‘The Abbot has sold everything in London, and doubtless within a year would have sold the house and lands, for white wine, sugar, burrage leaves, and seke, whereof he sips nightly in his chamber till midnight… For money to despatch the household and monks we must sell the copes and bells, and if that will not suffice, even the cows, plough oxen, and horse; the church we stir not. The grain crop is the fairest I have seen, and there is much meadow and woodland… Today we despatch the monks who are desirous to be gone. Yesterday, when we were making sale of the vestments in the chapter house, the monks cried a new mart [market] in the cloister and sold their cowls.’

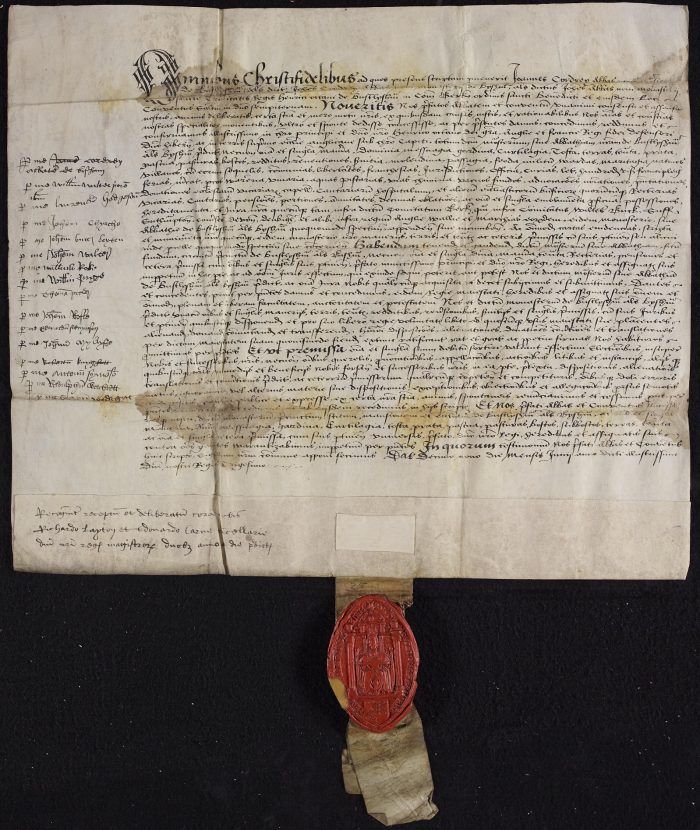

Shortly after, the monks were once again forced to surrender to the crown. The surrender is particularly poignant, as it was signed by each of the monks individually, with some of the names matching the names of monks previously recorded at Chertsey.

E 322/39 – Surrender of Bisham Abbey, 19 June 1538

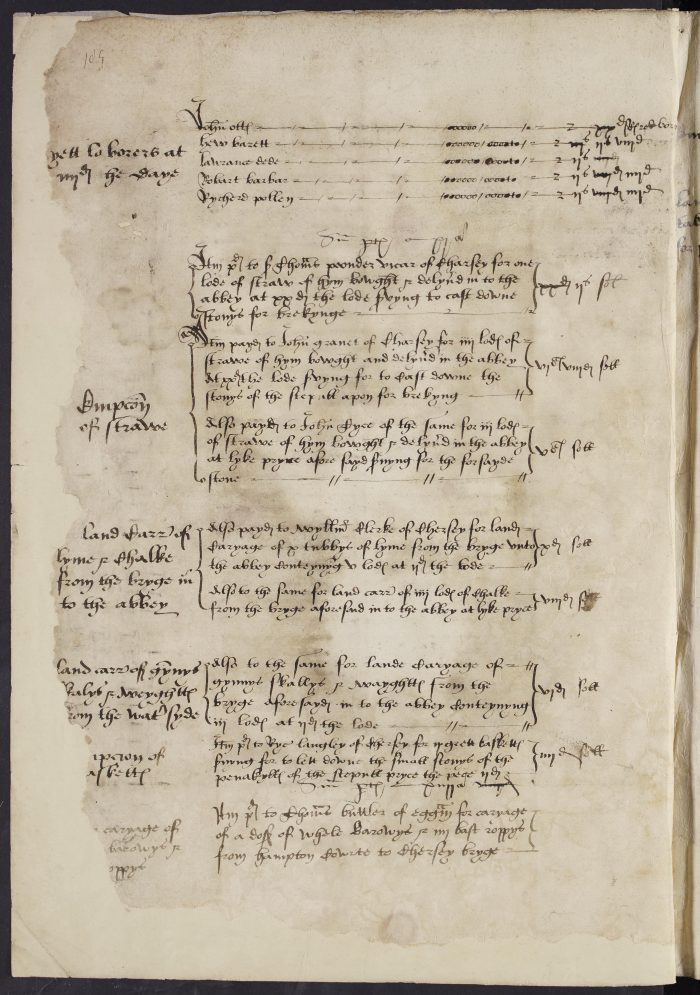

Three days after their surrender at Bisham, the monk’s old abbey in Chertsey was torn down. The accounts include daily wage entries for individual workers paid a penny or less an hour, working ‘their hours and drinking times’, including for ‘the hasty expedition of certain windows and doors’ to Oatlands Palace in nearby Weybridge.

E 101/459/22 – Accounts for the Dissolution of Chertsey Abbey, 22 June 1538

Some of the key entries for various works include:

- Item paid to Richard Langley of Chersey [Chertsey] for 2 great baskets, serving for to let down the small stones of the pinnacle of the steeple, price (per piece), 2 pence

- Item paid to Sir Thomas Poonder, vicar of Charsey for one load of straw, of him bought and delivered in to the abbey at 20 pence the load, serving to cast down stones for breaking

- Item paid to Thomas Buttler of Egham for carriage of a dozen of wheelbarrows and 3 best ropes from Hampton Court to Chersey bridge

The destruction of the abbey’s physical structure means that there are few ruined structures to see in Chertsey today (in contrast to Reading Abbey for example, where much of the structures survive to the present day). But the abbey hasn’t been completely forgotten; also on view in the exhibition is a new 3D computer model showing how it may have looked in 1362 during its heyday, showing the physical spaces in which the individuals in our documents lived and worked, but which sadly no longer exist[ref]The model has been created by James Cumper using archaeological reports, comparisons with contemporary buildings, educated guesswork and artistic license. As well as a two-minute ‘fly-over’ film giving an overview of the model, there is also an animated abbey time line and two games on an abbey theme[/ref].

Computer re-imagination of the 14th-century abbey – image credit James Cumper/Chertsey Museum

The exhibition will run until 2 November 2019. Our Education team run sessions on Chertsey Abbey – more details can be found on their web pages.

Really interesting, thank you Euan. A great companion piece to the exhibition.

A very fascinating history.

very interesting. tenkyu