Charles Stuart was restored to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland in May 1660. Such an outcome was a remarkable reversal of fortunes for an exiled king, who only the previous autumn had travelled to the Pyrenees in the hope of persuading the French and Spanish to back an invasion of England. When neither proved willing to support Charles, he retreated to his (relatively) meagre lodgings in Brussels.

The king had escaped England in 1651 and spent much of the next decade on the move; he firstly joined his mother at the French court before Cardinal Mazarin’s policy of allying with the English Protectorate saw Charles’s presence become a political embarrassment.

In 1654, Charles moved to Cologne, where promises of support largely failed to materialise. An alliance between Spain and France against the Protectorate next saw Charles settle in Bruges in 1656, which was then in the Spanish Netherlands, where the king was promised Spanish support for an invasion of England. Here he established the trappings of a royal court in exile, and we can witness the lamentable efforts to which the king and his courtiers went to create the pretence of a functioning administration. But it was all hampered by infighting, penury and a dreary sense of hopelessness.

Oliver Cromwell’s death in September 1658 initially failed to arouse much support for the king in England, and the royalists watched on with despair as Oliver’s son Richard was accepted as legitimate heir and proclaimed Lord Protector.

Cromwell’s death, however, had drastically altered the delicate balance of power that existed in London between the parliament, government and the army. Without his presence to control the Godly officers who served as MPs at Westminster; without his stubborn refusal to bow to the demands of the reforming civilian faction who had sought to reduce the army’s control over policy in England; but with massive debts incurred by maintaining such a large and threatening army, politics in London spiralled out of control as the army sought to protect its gains.

In April 1659, the army overthrew Richard Cromwell as Lord Protector. Again this was not the beginning of a restoration for the king, as politics in England remained very hard to read over the winter of 1659-60, thus Charles’ reasons for travelling to the Pyrenees in the hope of securing support. But channels of communication between royalists in England and Ireland and the exiled king increased when army factions in England sought to impose their will on parliament, and then on each other, resulting in coup and counter coup, leaving England without a functioning government.

Into this vacuum stepped General George Monck, commander of the Scottish army. It was his entry into England, followed by his arrival at London in February, that brought about the end of the Republic and ushered in Charles II’s return to London in May 1660.

Still, a restoration remained far from certain even in March 1660. Monck gave away little about his intentions and a restoration may not have been his goal. However, public opinion in London and elsewhere had grown weary of the army’s fighting and of the burden placed upon them to support the army through taxation.

Mostly, however, they seem to have become weary of the uncertainty. It was only after Monck’s demand in March 1660 that the Rump of the Long Parliament dissolve itself in order to make way for a new parliament that the likelihood of a restoration moved from a possibility to a probability. Elections to the new parliament, styled a convention as it had not been summoned by the king, were held in early April and resulted in a resounding success for candidates of more moderate political and religious leanings, so the king quickly relocated to Dutch territory, rebuffing belated offers of assistance from the French and Spanish as he sought to exploit the favourable political circumstances.

From Breda in the Netherlands, Charles sent a declaration on 4 April, through which provided reassurances to parliament, the army, the fleet and the City of London that he would rule through parliament, that religious toleration would be offered to ‘Tender Consciences … which do not disturb the Peace of the Kingdom’, and that he would only seek vengeance against a small portion of those men who had brought about his father’s execution. By doing so, he affirmed that he did not intend to restore Britain to a pre-Civil War position, but instead announced that he wished to govern through ‘king, peers and people’[ref]King Charles II, ‘His Declaration to All His Loving Subjects of the Kingdom of England. Dated from His Court at Breda in Holland, the 4 of April 1660’ (Journals of the House of Lords (London, 1767- ), xi, 7-8).[/ref].

When the declaration was delivered to the Convention Parliament on 1 May 1660, it was accepted first by the reconvened House of Lords (which was abolished in February 1649), and then by the Commons, and on 8 May the king was proclaimed as monarch. The way was now clear for him to depart the Netherlands and he sailed for Dover on 25 May 1660, arriving in London on 29 May, his 30th birthday.

Little of this process was straightforward and some of the best insights come from the ambassadorial dispatches sent from London to the capitals of Europe. One rich and accessible series is now called the State Papers Foreign, Venice, where the Venetian ambassador to London wrote to the Doge and Venetian senate as he tried to understand the shifting political environment in London, describing Monck’s manoeuvres and the dissolution of the Long Parliament, as well as the Convention’s move to restore the king.

We also get a clear picture of the king’s initial priorities in the days after he arrived at Dover and slowly made his way to London. Francesco Giavarina was the resident ambassador and he hurried to Dover to greet the king. He was afforded an audience because he was one of the few ambassadors who had refused to recognise the Commonwealth and Protectorate, and Giavarina reported that Charles acknowledged this. The ambassador also provides wonderful accounts of the celebrations as the king arrived back in London on and after 29 May, where the celebrations had to be brought to an end after three nights.

The ambassador’s accounts, however, weren’t fully accurate. He wrote on 11 June 1660 that no business had been done since the king’s arrival in London as Charles was ‘devoting himself to pleasing the people by his presence and in rewarding the deserving by making them knights'[ref]Transcriptions and translations of these records can be read in full at: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/venice/vol32/pp150-163.[/ref].

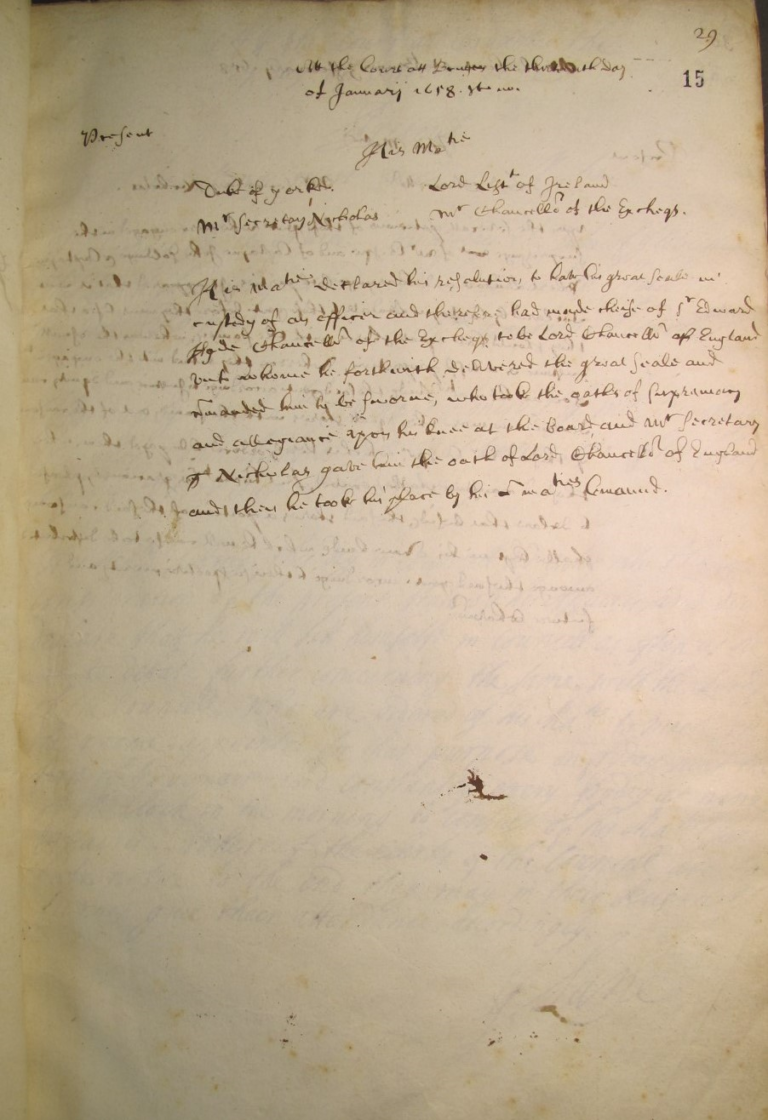

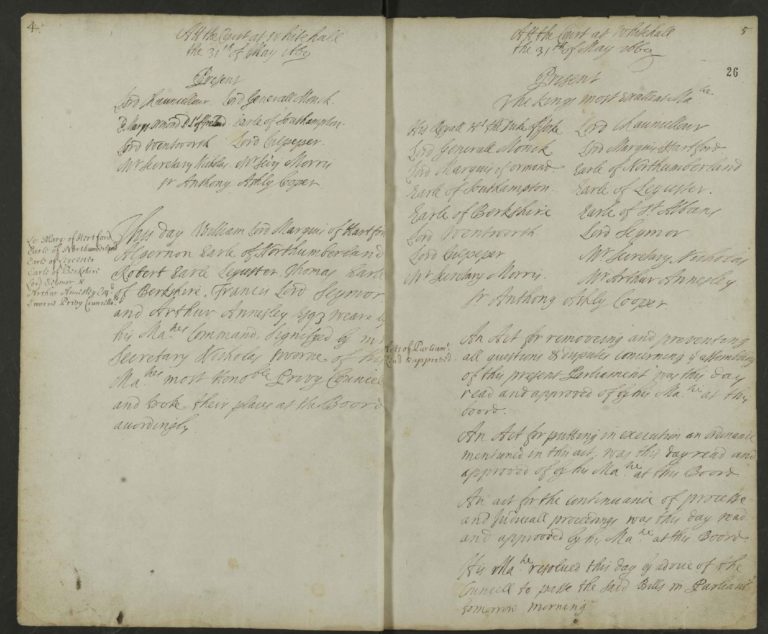

It’s clear that the king was intent on quickly consolidating his position. Charles convened his council for the first time on English soil at Canterbury on 27 May, but little business is recorded except for expanding the membership. The council met at Whitehall on 31 May, when the real business of government started. With the king present, the first matter was the need to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Convention Parliament, which had convened without the king’s assent. Thereafter, the council quickly addressed the need to ensure judicial proceedings continued uninterrupted so the legitimacy of the courts’ judgements could not be challenged. The king also ordered that the army and navy were to continue to pay their men. [The Privy Council Registers for Charles II’s reign have been imaged and are freely available to read on a database: Anglo-American Legal Tradition].

Declarations of loyalty also began to stream into Whitehall from across the Stuart kingdoms, as towns and cities proclaimed their loyalty to the king and his government, while hundreds of petitions were sent to the king seeking redress, especially from royalists who had suffered for the king during the Civil Wars and Interregnum. Such was the volume received that they now make-up whole volumes of letters within the State Papers[ref]https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/results/r?_srt=3&_aq=Petitions&_cr=SP+29&_dss=range&_ro=any&_st=adv.[/ref]. The king’s inclination was to indulge these as best as he could, but his ad hoc approach created multiple problems for his officials, especially over land ownership, so he was quickly encouraged to refer this issue back to parliament.

Royal government struggled to catch up with the volume of work in the weeks following the restoration of the king, but he was prompt in filling offices with officials, or re-appointing those doing the job whose loyalty could be trusted.

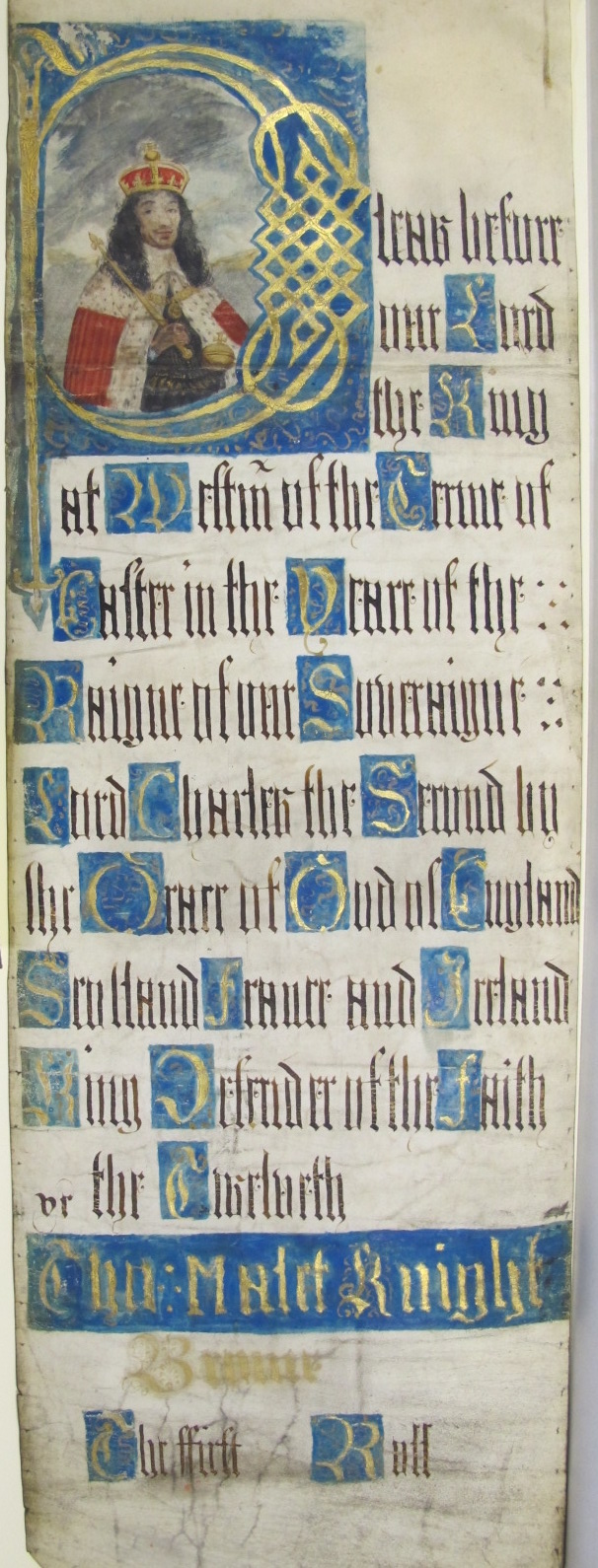

Perhaps a fitting image to illustrate how the trappings of monarchy had been restored with the person can be seen in the records of the Court of King’s Bench, where the king’s image was used to illustrate the Chief Justice’s plea roll for Easter term (9 May to 4 June 1660). Here was the king full of energy, keen to capitalise on his fortune in order to secure his kingdoms.

If you wish to read further about Charles II’s restoration, Ronald Hutton’s The Restoration: A Political and Religious History of England and Wales, 1658-1667 (Oxford University Press, 1986) remains an accessible and lively account.

Thank you for this post. I found it most interesting as it furthered my knowledge about the Restoration of King Charles II. Was surprised that it was a Scot who brought some order to the day.

I truly enjoy the many post covering such diverse subjects. Again thanks.

A really interesting post with great source links. Intrigued by the strong Venetian support and Giavarina ‘s closeness to Charles. Need to follow that up.

Many thanks.