On 5 April 1916, The London Gazette published the Royal Warrant (dated 25 March) instituting a new decoration, the Military Medal (MM), for non-commissioned officers and ordinary soldiers. The first awards of the medal were announced on 7 April to 32785 Serjeant F W Mallin and 5422 Acting Bombardier J J Pope, for actions during the German bombardment of the Hartlepools on 16 December 1914.

The decorations available to officers had been extended as early as 28 December 1914 with the creation of the Military Cross or MC, due to the many acts of gallantry in the first months of the war. Until the Military Medal was instituted, however, the only awards for most other ranks were the Victoria Cross, the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM), or a Mention in Despatches.

The decision to institute a new medal seems to have arisen purely in discussions between the King and Lord Kitchener. A file from 1918 (WO 32/3431) relating to the subsequent extension of the Military Medal to warrant officers (who though eligible for the MC had barely been awarded any) remarks:

‘The record [relating to decisions around the creation of the MM] is very incomplete, as decisions appear to have been arrived at verbally between the King and Lord Kitchener.’

The paper trail that does exist in the public record is largely to be found in three files now held at The National Archives:

These files are somewhat interlinked. In particular, WO 32/4960 and MINT 20/572 are often entirely complementary, with one having the file copy of a letter where the original is in the other (having been received from the originating department).

The main substance of the trail begins on 5 February 1916 with an note to ‘Creedy’ (Herbert James Creedy, Private Secretary to the Secretary of State for War) from ‘Ponsonby’ (Frederick Edward Grey Ponsonby, Keeper of the Privy Purse to King George V) stating that the King has approved of a new medal ‘for soldiers only’, to be called the Military Medal.

The note states that a design for the ribbon is enclosed, and that it should be passed on to Brade (Sir Reginald Herbert Brade, Permanent Under Secretary of State for War) to have the making of the ribbon put in hand, and designs for the medal drawn up. This seems to have come as quite a surprise to Sir Reginald, who immediately wrote:

‘Dear Ponsonby,

Do you know anything of this ?.

What are the conditions ? What sort of design and metal are we to ask for ? Is it to be a public charge ?.

Can you let me know all that is possible before we set the official machinery in motion.

Yours

(SGD) R H Brade’

Ponsonby replied on 7 February, explaining that it was to be for non-commissioned officers and men only; that is, all those who were not eligible for the Military Cross. The new medal was to have no gratuity attached to it (unlike the VC and DCM), and therefore, since it would reduce the number of DCMs being awarded, ‘it will probably be more an economy than expense’.

Kitchener and the King were most concerned that the ribbon for the medal should be made as soon as possible (as shortage of dyes was likely to slow production down), but the design of the medal itself could be resolved more slowly. To help with the design, Ponsonby asked for a specimen of the DCM to be supplied, he was already getting specimens of the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal and Distinguished Service Medal (both naval gallantry awards). Having presumably received these, Ponsonby wrote to Brade again on 9 February:

‘The King desires me to tell you that he wishes the obverse of the new Military Medal to be similar to that of the DCM. The attachment, however, should be similar to that of an ordinary War Medal. On the reverse His Majesty wishes a Crown and a circle of laurel leaves, somewhat in the style of the reverse of the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal for the Navy. The King is inclined to think that the plain words on the reverse of the DCM, look rather bald. His Majesty suggests that inside the circular wreath, the words “Military Medal for Bravery in the Field” should be stamped.’

Correspondence over various details of the design of medal and ribbon continued throughout February and March, and also drew in Lt Col Clive Wigram (assistant private secretary and equerry to the King), the Military Secretary, Major General Frederick Spencer Robb, and Sir Thomas Henry Elliott, Deputy Master and Comptroller of the Royal Mint.

The new medal was announced in the House of Commons by the Prime Minster, Herbert Asquith, on 24 February (though it was only stated to be ‘under consideration’). On 1 March, James Hogge (MP for Edinburgh East), asked Harold Tennant (Under Secretary of State for War), whether the new medal would be retrospective. Tennant replied that it would be open to commanding officers to take previous good service into account when drawing up lists of those to put forward. This wording, mentioning ‘good service’ rather than specifically ‘bravery in the field’, as the King had suggested (and Asquith had also originally stated) would lead to some confusion as to the exact purpose of the medal over the coming months.

By the end of the month, most details had been settled. The design for the reverse of the medal evolved from an initial sketch which appears to date from very early in the discussions, it carries no date, but is filed between letters dated 5 February and 9 February (all in WO 32/4960), with discussion as to the exact design of the laurel wreath, which crown to use, and precise wording to appear within the wreath.

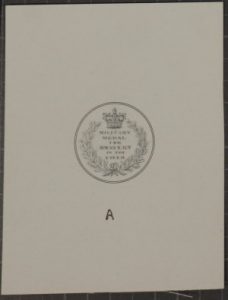

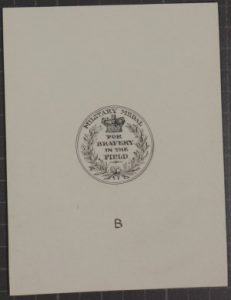

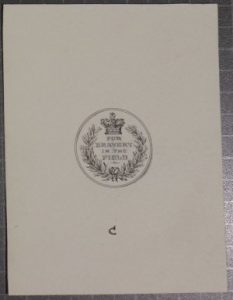

The Mint responded to each with a new sketch (or sketches), all in MINT 20/572. The first set seem to have been prepared on 22 February, three variants, labelled A, B and C:

- A followed the original suggestion for the design, with all the words ‘Military Medal for Bravery in the Field’ within the wreath; the Mint felt this this was too crowded

- B moves the words ‘Military Medal’ outside the wreath, allowing all the lettering to be a little larger

- C omits ‘Military Medal’, with an accompanying memo arguing that these were unnecessary since the obverse would show a military effigy of the King (whereas naval medals showed him in naval uniform), and it was self-evidently a medal rather than anything else!

- The first drawing in the second set of designs for the reverse for the Military Medal, labelled “A”

- The second drawing in the second set of designs for the reverse for the Military Medal, labelled “B”

- The third drawing in the second set of designs for the reverse for the Military Medal, labelled “C”

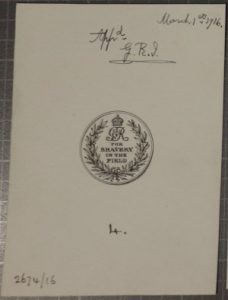

The King appears to have agreed with this conclusion, and so a further three designs were prepared, labelled 1, 2, and 3. These varied in the version and position of the Royal Cypher used, and the size of the crown. The Mint sent these on 25 February. It seems these crossed with a letter sent by the Privy Purse Office on 24 February which clarified a few details, and so a final design, labelled 4, was prepared and sent out on 29 February. This was signed-off by the King, ‘Approved GRI March 1st 1916’.

- The first drawing in the third set of designs for the reverse of the Military Medal, labelled “1”

- The second drawing in the third set of designs for the reverse of the Military Medal, labelled “2”

- The third drawing in the third set of designs for the reverse of the Military Medal, labelled “3”

- The final drawing design for the reverse of the Military Medal, labelled “4”

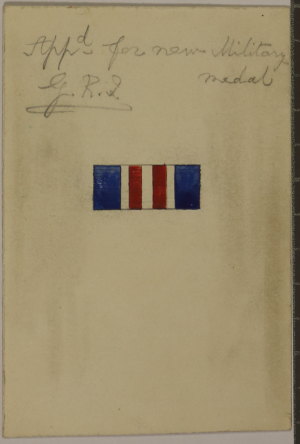

Meanwhile, the design of the ribbon was also being resolved. The design mentioned in the original letter of 5 February is now in an envelope marked 7B, the front has the ribbon design and the text, ‘App[rove]d for new Military medal [sic] GRI’, while the reverse is dated, ‘4th Febr 1916’.

A fabric sample was received on 21 February, and laid before the King with the final design for the reverse of the medal on 1 March. 1008 yards of ribbon were ordered from Walker Barton & Co on 2 March, with promise of delivery in 10-14 days.

The first sample of fabric for medal ribbons that was provided to the War Office

There were still a few minor details to iron out in the design of the suspension bar and so on which took a little longer to resolve, so it was not until mid-April that a specimen medal was supplied to the King. This seems to have been longer than some of those in Parliament had hoped, and questions were asked in the House on 12 April (by Sir Arthur Markham – this session does not seem to be available in the online Hansard, but a copy is in MINT 20/572) as to why the institution of the medal was taking so long. Tennant replied that the decoration had been formally instituted by the Warrant dated 25 March:

‘There has been no delay other than has necessarily been involved in the processes of design and manufacture of both the medal and the riband.’

Unfortunately the Mint took this as meaning that they had been slowing things down, though this was eventually smoothed over.

It was also at this time that the repercussions of the original statement in the Commons by Tennant begin to be felt with queries as to what the precise conditions of the award were. Tennant continued to imply that it could be given for good service other than merely ‘bravery in the field’ despite the wording in the Warrant. In France and elsewhere recommendations were being prepared on the basis of ‘good service’ only, and WO 32/4960 indicates that some of the awards gazetted in the 1916 King’s Birthday Honours were indeed on that basis.

However, by the end of June it was being made clear that awards really should be for bravery only. It was agreed that recommendations that did not meet this criteria should be converted to recommendations for the Meritorious Service Medal (MSM), with appropriate modifications made to the warrant for that award (which had previously been restricted to men with long service and of particularly high character). This was agreed on 28 June (see files such as WO 32/4958 for details to changes to the MSM itself).

Another issue to be resolved was whether the MM should be awarded to colonial forces. It was generally assumed that it would be available to the Dominion forces (Canada and Newfoundland, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa), but not India, as additional decorations were already available within the Indian Army. In some of the African colonies there was also the African Distinguished Conduct Medal available to locally raised troops, awarded through the Colonial Office, rather than the War Office. The decision appears to be that where such units were serving with British forces, it would be possible to award the Military Medal.

The final matter raised within WO 32/4960 is the possibility of making awards of the Military Medal to women in special circumstances. This matter is taken up further in the third of the files mentioned at the beginning of this post, WO 32/4959, but will be examined further in a future blog post.

I would add that there is another file (T 333/257: 1914-1984: Military Cross) which is temporarily withheld by the department (but an FOI should release it or part of it), in this case the Cabinet Office to whom responsibility of the former Ceremonial Branch now falls to.

David,

Thank you, though actually T 333/261: Military Medal: 1916 Feb 07 – 1979 Apr 18 http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C11223561 might be even more applicable – and handily is not retained (perhaps because awards were suspended in 1993 and the Military Cross opened to all ranks). I’ll take a look at some point and see if it does add more to the story. As I mentioned I was going to follow up with a further post looking at how the MM was opened to women, so it will be useful to see if there is specific mention of that issue.

David,

Thanks, strange, when I checked this morning it was retained!.

David

T 333/257 that you referred to, on the Military Cross, is retained. T 333/261 on the Military Medal, is open.

Thank you for a very informative article. However, the wrong impression is given that the creation of the MC in 1914 two years before the MM meant decorations available to officers had been extended before a similar extinction to other ranks. In fact, the exact opposite is the case with junior officers having always been the least favoured when it came to decorations. The DCM was created in 1854 for other ranks and it was not until the VC was created two years later that there was a decoration for junior officers. Between 1886 and 1953, the DSO an award for distinguished service and leadership, and not a gallantry award was in a minority of cases granted to junior officers for gallantry. It was only in 1993 that Army officers were eligible for three gallantry awards the VC, CGC and MC which Army other ranks achieved with the creation of the MM in 1916.

Thank you Anthony.

I’d argue that in effect the DSO was treated as a galalntry award – it’s certianly not that difficult to find citations explicitly referring to gallantry, for example all those here https://www.thegazette.co.uk/Edinburgh/issue/13038/page/117 come under the heading “His Majesty the KING has been graciously pleased to approve of the appointments of the undermentioned. Officers to be Companions of the Distinguished Service Order in recognition of their gallantry and devotion to duty in the Field”, and gallantry is again mentioned in each individual citation.

In addition, the MM was explicitly set up to cater for those not eligible for the MC (hence the initial exclusion of warrant officers from eligibility), so in that sense it does seem to me like a “follow on” to the creation of the MC.

It’s a fair point though that it was probably still harder for junior officers to be decorated (and you might say that this is particularly true in view of the proportionally higher casualty rates among subalterns).

[…] this week, with my work hat on, I published a post on The National Archives’ blog, looking at the centenary of the institution of the Military Me…. It gives background info on the medal, and how it came into […]

It is a pity that this medal, along with it`s RN and RAF equivalents, was abolished. It might have been preserved with a revision of award criteria, thus preserving the historical continuity of the decoration.

Hi David, a lovely article on the institution of the MM which Howard Williamson and I will be building on for the publication of the Military Medal 1914 to 1939 in 2017.

As the first awards gazetted are historically important, just to be accurate, the award to Pope was incorrectly spelt as it should have been Hope which his MM card confirms.

Thanks Chris, I enjoyed the talk you gave on the work you’ve been doing. Just shows no single source can be entirely trusted, even one as August as the London Gazette.