The August bank holiday weekend is iconic as the weekend of Notting Hill Carnival when millions descend on Kensington to celebrate Caribbean culture, dance and have fun; but it’s also a tradition deeply rooted in political origins.

Carnival was a radical and novel response to racial tensions that had been growing across London, and indeed across the country as illustrated by the 1963 Bristol Bus Boycott and Nottingham race riots.

At this moment London was becoming a thriving multicultural hub caused by an influx of post-war economic migration. These were the ‘Windrush’ generation – new to the country and culture looking to find jobs, stability and a home. Government records show appeals for NHS nurses from commonwealth countries to help support the growing population. However many black people had been living in London before this time (as can be seen in a previous blog post on black British civil rights covering the 30s and 40s). While the colour bar (a social system in which black people were denied the same rights as white people) was never enforced in Britain, racial discrimination was often a reality at this time.

The same notorious August bank holiday weekend in 1958 had seen the Notting Hill race riots, five nights of riots instigated by a white mob, in which 108 people were ultimately arrested.

Tensions further escalated in May 1959 by the unsolved murder of Kelso Cochrane. Cochrane, a West Indian carpenter, was walking home from hospital at midnight when he was attacked by a group of white youths in Notting Hill, at this time a stronghold for Oswald Mosley’s fascist movement. This moment further polarised the West Indian community in London. On 6 June 1959, 1,200 people joined his funeral procession in solidarity from St Michael and All Angels Church to Kensal Green Cemetery. The iconic news reel can be viewed on British Pathé.

“To practice our cultural heritage and keep it alive”

These catalysts were turning points for a community increasingly feeling ostracised in their homes.

In response, a Caribbean carnival was held on 30 January 1959. This positive event was designed to combat some of the negativity caused by the Notting Hill race riots and the murder of Kelso Cochrane by celebrating West Indian culture and bringing people together.

The event was an indoor carnival organised by Claudia Jones. Often described as ‘the mother of the Notting Hill Carnival’, Jones was a communist campaigner and fighter for black civil rights. The carnival ran annually until her death in 1964 funded by the West Indian Gazette, of which she was founder and editor. Marika Sherwood notes, ‘There is no record of Claudia undertaking any independent political activities before the riots’. Like many others she was politically energised by the race riots to act on the social struggles she saw around her. [ref] 1. Sherwood, Marika, Claudia Jones, A Life in Exile (London, 1999), p. 92 [/ref]

Carnival wasn’t the only response to the situation. Political movements gathered momentum, with both the Coloured Peoples Progressive Association and the Association of Advancement of Coloured People founded around this time.

Several years later, in 1966, there was the first outdoors carnival, led by Rhaune Laslett, a local white community campaigner – and Notting Hill carnival began to become the event we know of today.

Both these coinciding events show the need for something like carnival for the community.

The aims of the West Indian Steel Band and Cultural Association explicitly picks up these themes, showing what the event meant to the community, declaring their aims:

‘To practice our cultural heritage and keep it alive. Thereby adding stability to the West Indian Community resident in Great Britain, and to create respect for our people through our cultural activities. We hope to foster good relationships between indigenous and all minority groups, (as has been our experience in the multi-racial society of the West Indies), by making a contribution to the community in which we live and work, adding to its richness and way of life’ (CK 3/38)

Controversy

The National Archives files on carnival paint a picture of community relations, police negotiations and mass organisation on both sides to make the event happen – from consultations on road closures, to whether the event would happen at all.

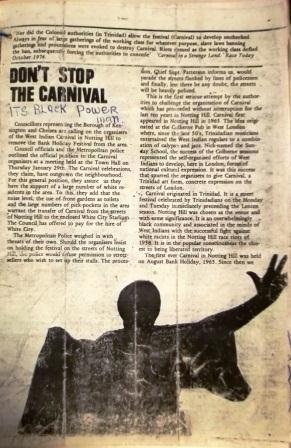

Community responce to a petition by local residence to stop carnival in 1975 (catalogue reference: MEPO 2/10891)

In the late 70s a conflict between the two carnival organisational committees triggered fears the carnival would be called off (WORK 16/2547). The location was often questioned as carnival expanded with everywhere from Hyde Park to Stamford Bridge football ground considered as a possible venue. Files reveal that in 1976 locals petitioned to stop carnival, triggering protests in response to protect the Notting Hill Carnival – one pamphlet issued the rallying cry, ‘We negotiate from a position of power, and this is certainly not the first time in the history of Carnival that we have had to put up a struggle to control the streets for the celebration.’ (MEPO 2/10891)

The journey to the event today was not a smooth one, but community organisations always rallied together to keep carnival happening – after all Notting Carnival is the freedom to celebrate culture loudly and proudly, and have fun at the same time.

The words of the Notting Hill Carnival Development Committee seem an appropriate close: ‘The idea was to bring to the drab streets of North Kensington a “little bit of heaven” and to enable the West Indian Community to feel at home in a country to which it is historically and spiritually tied.’ (CK 3/38)

Look out for more events on black history soon, particularly focusing on the trial of the Mangrove Nine.

[…] Carnival: bringing a ‘little bit of heaven’ to Notting Hill […]