Feb 1782. Royal decree authorising the commissioning of Sir Guy Carleton at New York, as Commander-in-Chief of His Majesty’s forces in North America; complete with the first great seal of George III (catalogue reference PRO 30/55/101/1).

Having been given an exciting opportunity to project manage the cataloguing of the Carleton Papers (record series PRO 30/55), since September 2016 I have been supervising this volunteer-led project. The private collection of (Ashley family) papers of Sir Guy Carleton, first Baron Dorchester, relate to British Army Headquarters for North America correspondence between 1748 and 1788, and are largely concerned with the American Revolutionary War. Carleton was to succeed General William Howe and Sir Henry Clinton as the last Commander-in-Chief in North America. These (‘Dorchester’) papers were originally collated by Maurice Morgan, secretary to Carleton; the collection itself was presented to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II by President Eisenhower in 1957, as a gift from the archives of Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia.

Managing a small team of dedicated volunteers, I have produced this blog post in partnership with Eileen Wicks who, as an early recruit, was my longest-serving volunteer. The cataloguing of this under-used archival resource has been an excellent achievement by all the individuals concerned, with the release of a total of 107 pieces to our Discovery catalogue, some four months ahead of schedule.

Comprising 30,000 manuscript pages, the collection was rebound into the present volumes by the New York Public Library between 1934 and 1935. Arranged in chronological order, each volume contains a run of papers representing the dispatches of the successive commanders-in-chief; the collection also includes correspondence with the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Many of these letters concern the American ‘Patriot’ forces, and are often sent by George Washington himself (see PRO 30/55/66/91 which relates to news of a general peace in April 1783, for example).

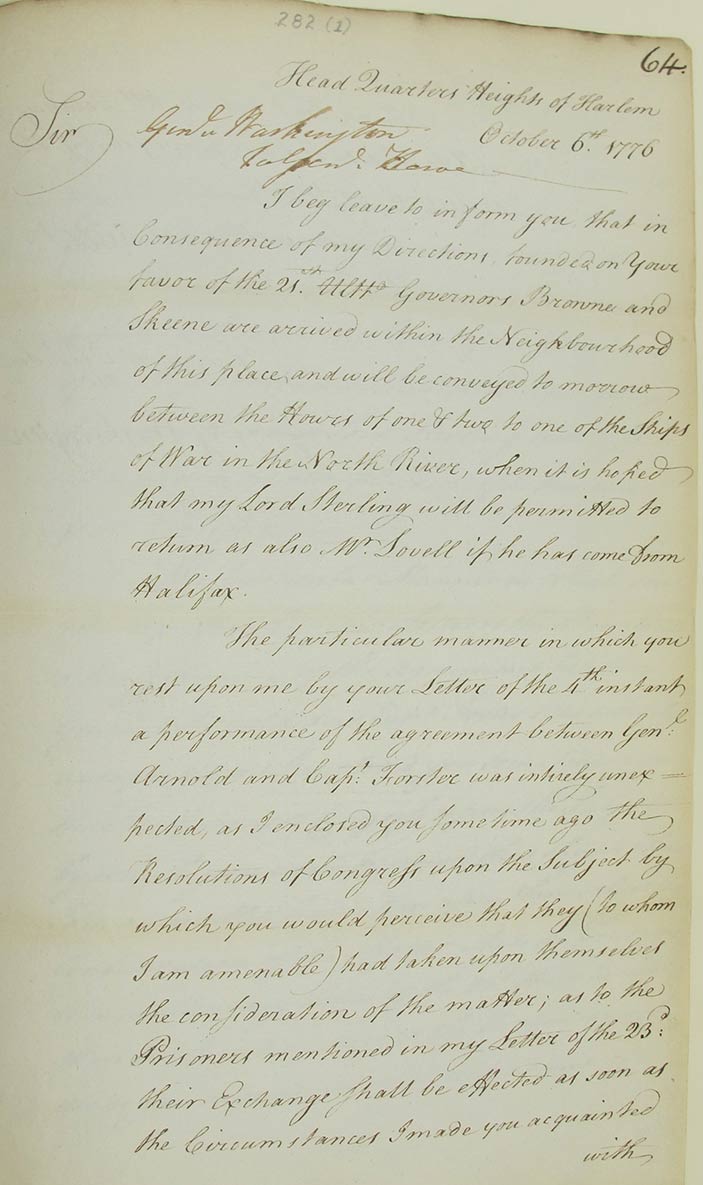

Oct 1776. Letter from Washington to General Howe, concerning prisoner exchanges after the Battle of Harlem Heights (catalogue reference PRO 30/55/3/64).

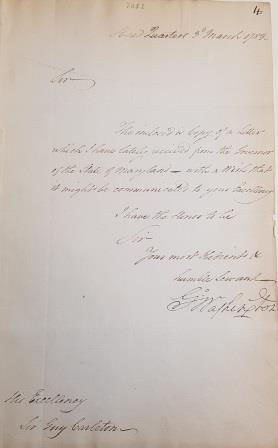

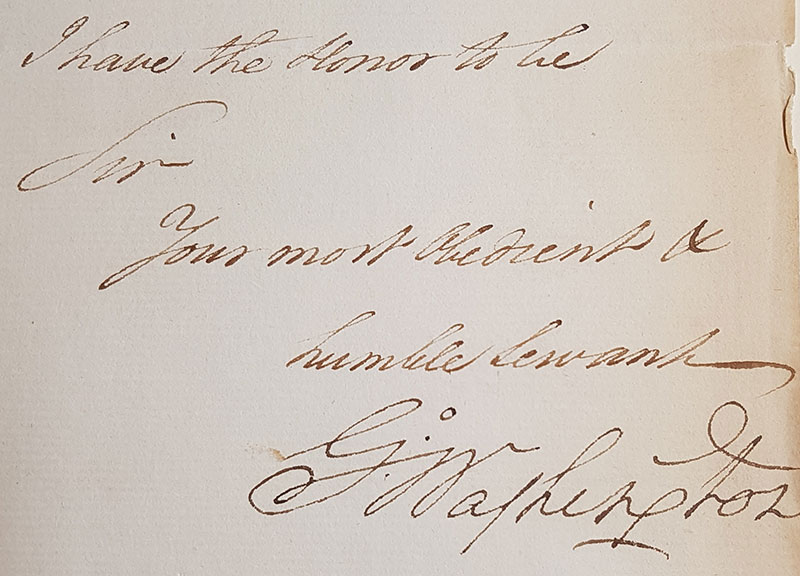

March 1783. General Washington to Carleton. Sending an enclosure from the ‘Governor of the State of Maryland’, complete with the signature of George Washington (see below). Catalogue reference PRO 30/55/64/13.

Persons both famous and infamous are often referenced: these include the subsequent statesman and political theorist Edmund Burke, who was paymaster general to the forces; Ethan Allen, who negotiated with Governor Haldimand of Quebec to establish Vermont as a new British province; George Rogers Clark, who led the successful Continental expedition to the Illinois country (encouraging the alliance with France); the ruthless British light horse officer (of the southern theatre of war) Banastre Tarleton; and the American arch-turncoat Benedict Arnold.

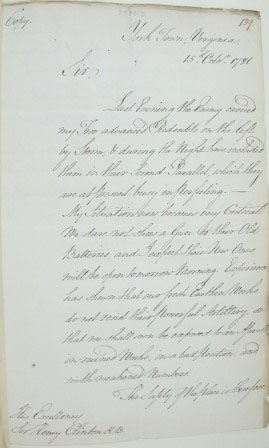

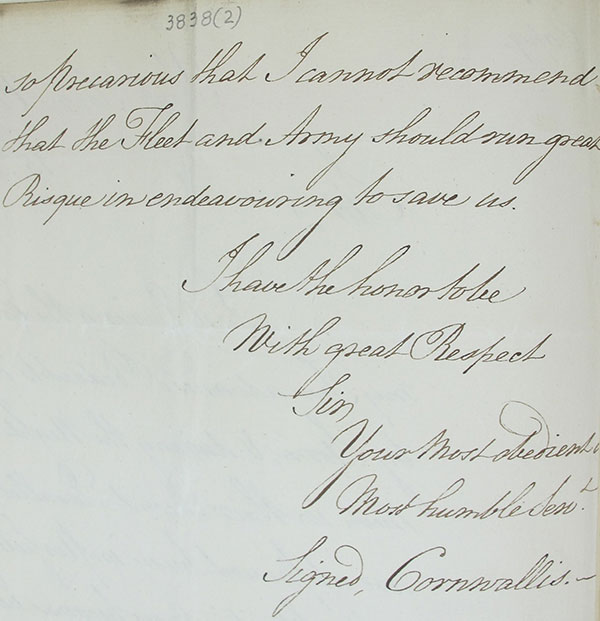

Oct 1781. Dispatch from General Cornwallis to Clinton regarding the critical state of the defences of Yorktown, Virginia (catalogue reference PRO 30/55/33/32).

Copy (reverse of the dispatch) sent by Charles, Earl Cornwallis (catalogue reference PRO 30/55/33/32).

The cataloguing work, populating item-level descriptions of the volumes in Discovery, uses text found in the published ‘Calendar Reports on American Manuscripts in the Royal Institution of Great Britain’ (HMSO no.59, 1904-1909). A revised summary of each of the manuscript pages has now been entered into the catalogue, giving a much clearer indication of the contents of each document, allowing for a more accurate and comprehensive search.

The American War itself evolved from a complex set of grievances over taxation (intensified by the notorious 1765 ‘Stamp Act’ which imposed a direct tax on printed materials), disputes over military defence, western expansion and, above all, the issue of parliamentary representation for the original 13 colonies. In 1775, George III’s government considered American opposition to be little more than belligerent disloyalty and open rebellion. By the time that France and other European powers (namely Bourbon Spain and the Dutch Republic) entered into the conflict after 1778, in support of the colonial cause, it had turned from what was essentially a civil war into an international struggle. The official cessation of hostilities only occurred with the Treaty of Paris in September 1783, and the emergence of the new United States.

Centred on New York and the Atlantic seaboard, the material is wide-ranging: for example, it includes dispatches from the north-western frontier, and Upper Canada, along with intelligence reports from the West Indies, and the southern colonies of Georgia and the ‘Floridas’. These records are a particularly rich source. They highlight relations with Spanish Louisiana (which extended far into the Trans-Mississippi West), and with regional American Loyalists, like Colonel John Butler, whose provincial ranger companies were active in the Mohawk Valley. They also give insights into relations with the various Indian nations, many of whom – like the Creeks, for example – were largely allied to the British (or, in the case of the Cherokee and the once all-powerful Iroquois, would be bitterly divided by the conflict).

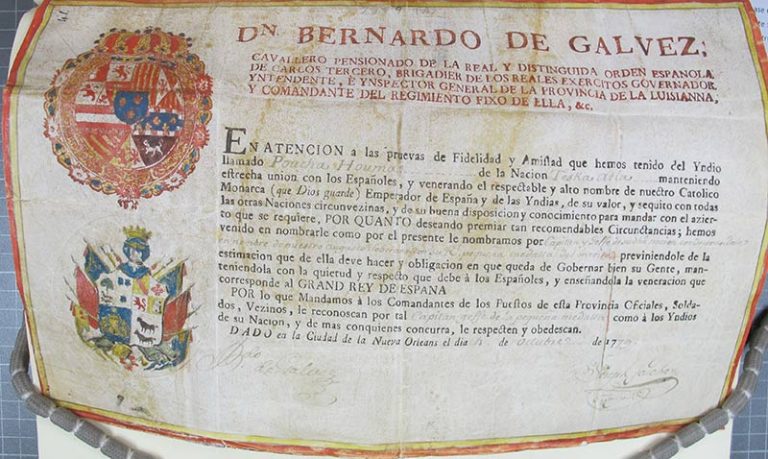

3 Oct 1779. Authorisation by Don Bernando De Galvez (in the name of King Carlos III) at New Orleans, as governor of Spanish Louisiana. Appointing Poucha Houmas of the ‘Teskaatla’ tribe as ‘captain and chief of the southern nation’ (catalogue reference PRO 30/55/19/68).

![Sept 1777, [Alexander] McGillivray, Creek Indian leader to [John] Stuart, Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Intelligence report showing the scale of the distances of the [Upper Creek] Indian towns, and of the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations from St Augustine, and Pensacola (catalogue reference PRO 30/556/103).](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/01144707/Cart-4-Ind-towns-768x777.jpg)

Sept 1777, [Alexander] McGillivray, Creek Indian leader to [John] Stuart, Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Intelligence report showing the scale of the distances of the [Upper Creek] Indian towns, and of the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations from St Augustine, and Pensacola (catalogue reference PRO 30/55/6/103).

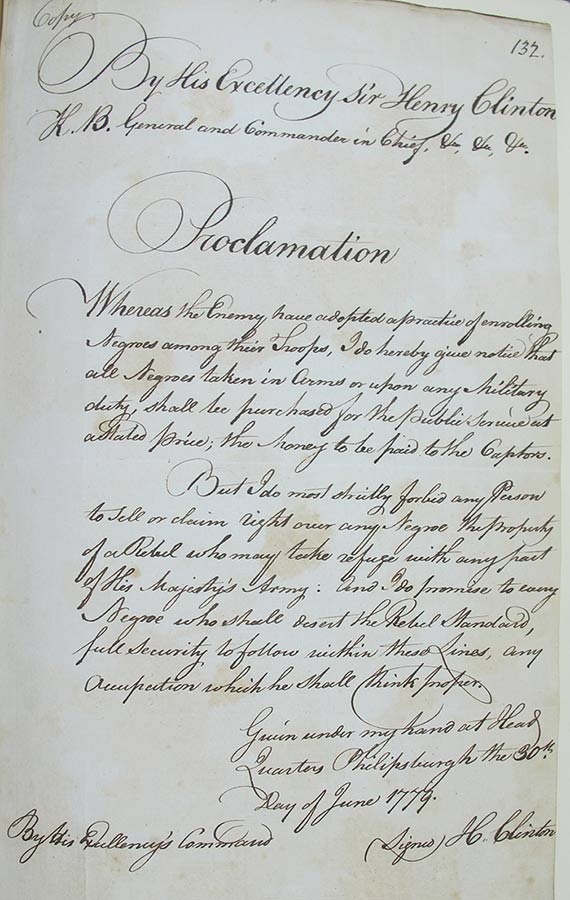

June 1777, Proclamation of Philipsburg (catalogue reference PRO 30/55/17/63).

Among some of the most interesting finds are: proposals in 1775 to hire 20,000 auxiliaries from Catherine the Great of Russia for service in the colonies (in PRO 30/55/1/32); the Articles of the Convention of Saratoga, which followed General John Burgoyne’s surrender to the Continental army of the London-born Horatio Gates in 1777 (PRO 30/55/6/112); and the Proclamation of Philipsburg in 1779, which encouraged slaves to run away from their American ‘rebel’ owners and enlist with the Crown’s forces (on the promise of freedom and land).

However, the material is not exclusively related to military concerns. It brings to light an array of other subject matters, including the situation of both male and female civilians (at all levels of society, and on both sides of the political divide) and, at a more intimate level, how people and places were affected by the decisions of government, the effects of war, and of their banishment and enforced emigration.

![Feb 1782. Report on the House of Commons resolutions [by the Rockinghamite Whigs] against continuing the war in the colonies (catalogue reference PRO 30/55/36/34).](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/01144709/Cart-8b-HoC-Res.jpg)

Feb 1782. Enclosure reporting on the House of Commons resolutions [by the Rockinghamite Whigs] against continuing the war in the colonies (catalogue reference PRO 30/55/36/34).

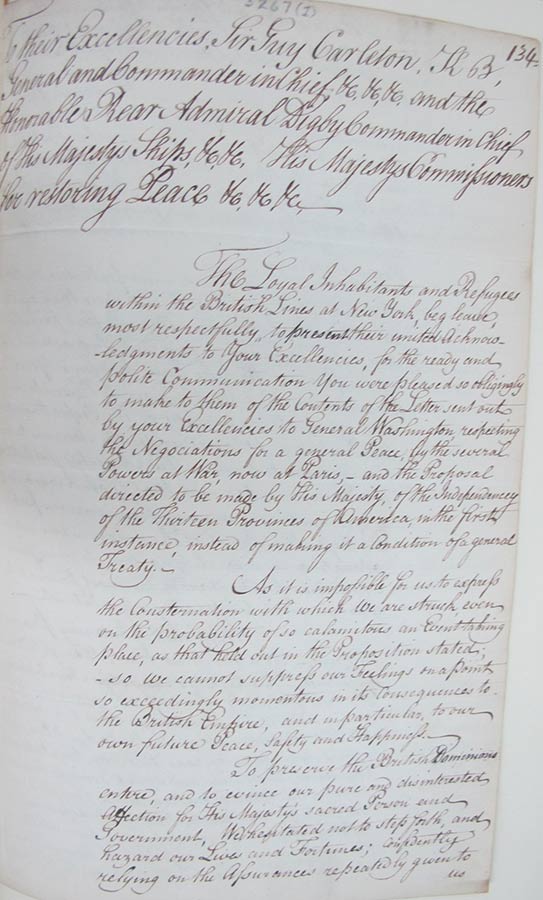

Aug 1782. Address of the loyal inhabitants and refugees within the British lines at New York, with regard to the negotiations for a general peace ‘by the several powers at war now at Paris’ (catalogue reference PRO 30/55/46/58).

While military history remains a very popular research trend among academic and public history researchers, we hope that the North American user community will also find much of value in this collection, for studying social history and historical geography.

Ultimately, this has been a fantastic effort by all concerned. It has truly been an honour to be involved with this enterprise and to manage such an enthusiastic team.

Greetings,

I just came across your blog and as a member of “the North American user community” (Wallingford, Vermont), I applaud your efforts at creating a detailed catalog for the collection.

I’d also like to ask if there are any plans to digitize the collection. Currently, I have to drive about 65 miles one-way to access the microfilms. I also have to let the facility know ahead of time which reels I want to look at so they can retrieve them from the stacks. I would like to be able to explore the documents at my leisure while sitting at home in my bathrobe.

Hi Mike,

Thank you for your kind comments regarding my Carleton Papers blog.

Other than being able to view summaries of the individual correspondence on our Discovery catalogue, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/browse/r/r/C3070339

there are no plans at present to digitise this collection.