I imagine the past couple of weeks have been pretty busy for the British Embassy to the Holy See, but they probably have nothing on 1978, otherwise known as the Year of Three Popes.

Pope Benedict XVI’s recent decision to step down as leader of the Roman Catholic Church – the first pope to abdicate in almost six centuries – opens the way for the unusual situation of two popes living in the Vatican at the same time.

In 1978, in the space of three tumultuous months between August and October, the Roman Catholic Church had no less than three different leaders: Pope Paul VI, Pope John Paul I and Pope John Paul II. I’ve been looking back through the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) files from the period to see how British officials at the legation (as it was then) in Rome dealt with the fast-changing situation.

Poland's Cardinal Wojtyla became the third pope of 1978. (catalogue ref: FCO 33/3787)

I often find that Foreign Office correspondence – far from being the dry, diplomatic cables that many people expect – are a rich source of descriptive information and local ‘colour’, for want of a better word. Something the author Matthew Parris successfully mined in his recent book of Foreign Office letters: ‘The Spanish Ambassador’s Suitcase’.

Geoffrey Crossley, Britain’s envoy to the Holy See, recorded his first impressions on arriving in the Vatican in March 1978, little knowing what an eventful year lay ahead. Despite being a Foreign Office veteran of more than 30 years service, he seems to have been somewhat overawed at first, describing ‘a feeling of humility, caused not by the pomp and ceremony, gilt and marble of the richly frescoed Vatican, but by my realisation of how ignorant I was of the nature and working of the great machine that runs the Roman Catholic Church.’

Fifteen years earlier, Lord Norwich wrote memorably about his attendance at the Coronation of Pope Paul VI, where he was accompanying the Queen’s representative, the Duke of Norfolk.

Attending a party in honour of Commonwealth Cardinals, his first impression was one of ‘riotous colour’. He continued: ‘It seemed at first sight remarkable that a cocktail party of which the guest list was some seventy to eighty percent male should prove to be one of the most visually dazzling I have ever attended; but then I had never before seen Cardinals by candlelight.’

Cardinal Gracias of Bombay apparently stood out, he was, according to Lord Norwich, ‘as worldly as the others were withdrawn, cigarette in one hand, mahogany-coloured whisky-and-soda in the other, talking cricket as only Indians can.’

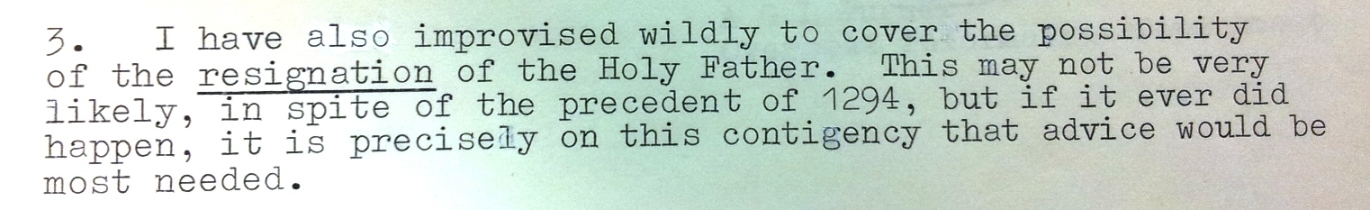

Even before Pope Paul VI’s death was announced to the world in August 1978, his decline in health and non-appearance at Easter services had alerted FCO officials to the possibility of a change at the top. Much of the files are taken up with discussion of the correct protocol surrounding the death, or interestingly, the resignation, of a pope and the coronation of his successor.

Catalogue ref: FCO 33/3784

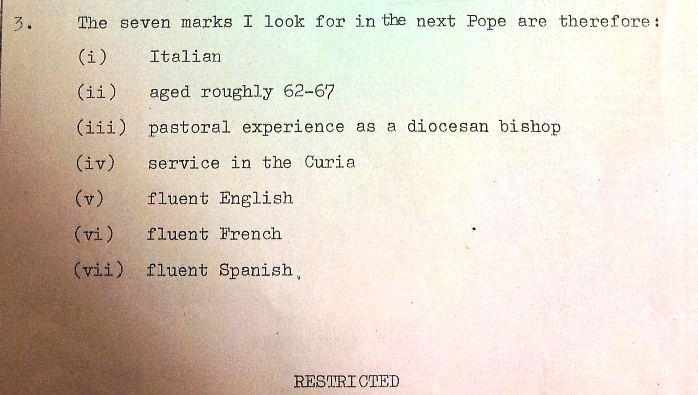

There was also, much as now, a great deal of speculation about who might take over. Despite an admission that such a task was largely ‘guesswork’, Adrian Turner of the FCO’s Overseas Information Department, produced a detailed memo in May 1978 entitled ‘The Next Pope?’ which listed seven key qualifications for the job. The ideal candidate should be (i) Italian, (ii) aged roughly 62-67 (iii) pastoral experience as a diocesan bishop (iv) service in the Curia (v) fluent English (vi) fluent French (vii) fluent Spanish.

Note from A.G.L Turner, 10 May, 1978. (catalogue ref: FCO 33/3784)

With several bookmakers now offering odds on who will be the next pope and newspaper profiles of the likely candidates often listed under ‘runners and riders’ it sometimes feels as if the race to be the next pope is exactly that, a race, albeit one only run every decade or so.

It must have felt the same in 1978. Mr Turner’s analysis of the papal contenders prompted his colleague David Goodall in the Western Europe Department to call it the ‘best informed and most perceptive piece of pre-election analysis which I have seen.’ He was particularly impressed by the fact that Cardinal Luciani, the man who eventually became Pope John Paul I, was among the list of contenders when few people had picked him out beforehand.

He concluded: ‘If you ever decide to turn your talents to horseracing, I hope you will let me know so that I can benefit from your expertise!’

Sadly Pope John Paul I’s reign was to be a short one. He died just 33 days after taking office and Mr Turner’s prediction skills were called upon again, this time in a memo entitled: ‘The Next Pope: the same – but different?’ on 9 October 1978. Turner picked Cardinal Pignedoli from a short-list of three but added that ‘I am glad I do not have to be infallible.’

Interestingly, given that in this year’s conclave, Cardinal Turkson of Ghana is considered one of the front-runners, another piece of pre-election analysis, this time from a Mr Michael Cafferty, pointed out that although Cardinal Gantin of Benin was ‘well-spoken of… I wonder whether the world is ready for a black pope’.

In the end, the choice of Conclave II, as it was dubbed, was almost as surprising. A little known 58-year-old cardinal from Poland was elected as the first non-Italian pope for more than 400 years. He took the name John Paul II.

The choice of man under 60 was itself surprising, as one note says, quoting a Vatican source, ‘We want a saintly pope but not an eternal one’.

In Warsaw, the FCO reported, the news of the election of a Polish pope had hit the country ‘like a bombshell’ and caused an immense surge in national pride.

Describing John Paul II’s inauguration a few weeks later, our man in the Vatican, Mr Crossley, also seems to have been caught up in the drama of the occasion: ‘The mass media may not…have been able to convey fully the highly-charged atmosphere of excitement evident to those actually present in St Peter’s Square. The fact that we were witnessing the installation of the first non-Italian pope for over four centuries was in itself of special interest. But as the strong resonant voice of the pope, in contrast to the frail 80 year old voice of Pope Paul VI and the soft falsetto of Pope John Paul I, rang across the square the audience was gripped by his extraordinary impact.’

Tommy,

Very interesting. Did you know that Pope Paul VI was elected in 1963 (another recollection of this important year). There is a very interesting account (In Italian) in SP 9/100/14 “Accounts of the Conclaves in which the following Popes were elected: Gregory XIV (1590), Pius IV (1559), Sixtus V (1585), Pius V (1566), Paul V (1605), the last by Giovanni Paulo Mucante, Master of Ceremonies of the Pope” and which dates from the 17th century.

The views of the FCO show how the assumption was that the Pope had to be Italian and which these days seems to be outdated, a bit like an Italian driving the Ferrari F1 car, it should in my view be whoever is best.

David

Thanks David. Yes, we’re just a few months short of the 50th anniversary of Pope Paul VI’s coronation – he was incidentally, the last pope to be actually ‘crowned’. Lord Norwich’s lively eyewitness account of the proceedings, ‘Notes on a Papal Coronation 1963’, part of which I’ve reproduced above, is very entertaining and reads almost like a short-story [FCO 33/3785].

I agree with you on the question of Italian candidates, although even today Italy has more eligible cardinals in the conclave than any other country as well as the current favourite with the bookmakers, Cardinal Scola.