The Prize Papers Project has now been running since May 2018, with the team at Kew working on the physical records, and the University of Oldenburg team working on the digital images and website (www.prizepapers.de).

Since then we have worked in two main areas for the digitisation pipeline. The first to be completed was the collection of printed prize appeals from the London court and the many colonial Vice Admiralty Courts for the wars of 1793-1815 (see Introducing the Printed Prize Appeals: Selected examples from HCA 45).

Our major focus however was on the War of Austrian Succession, 1739-1748, chosen as a mid-sized tranche with some archival work already done on it.

Despite losing over a year to lockdown, we have successfully identified and catalogued 1,303 ships taken by the British in this war, captured near enough to Britain to be adjudicated before the High Court of Admiralty in London. This generally means ships captured in the North Sea, English Channel and the eastern Atlantic – ships captured elsewhere were usually handled by the nearest colonial Vice Admiralty Court, whose records may not survive for this period. Exceptions are for ships brought into Lisbon or Livorno, where the British consul examined the crew and sent the results off to London.

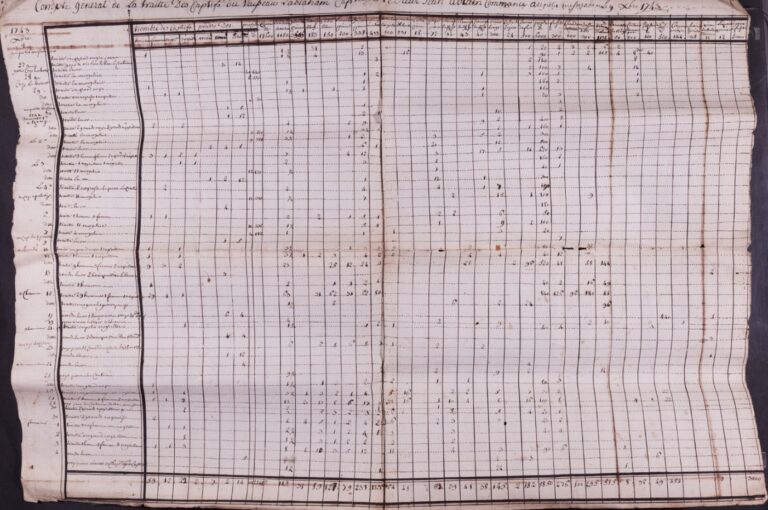

These ships between them were carrying 34,038 documents (still surviving in the series HCA 30 and HCA 32). A minimum of 13,000 of these are letters etc, either from seized mailbags, or from the personal archives of passengers and crew. The papers generated in the court cases – to prove them either enemy and therefore good prize and sellable or neutral – supplied a further 15,123 documents. Neutral ships had their papers returned: the court kept lists and translations of them, creating a kind of ‘ghost archive’.

These 34,000 papers have all been sorted, identified and numbered, ship by ship, and are now part way through being conserved and digitised. They are being released in themed batches on www.prizepapers.de, with much more searchable detail about individual documents.

Archival problems

The Prize Papers from this war last received archival attention in the 1950s by Charles Gaskoin, as a retirement project. It is not clear if the papers were originally arranged by type (as in previous wars) or by ship (definitely done by 1793). Large collections of letters had been kept (and sometimes scattered) among the court’s miscellanea in HCA 30, described only as ‘French’ or ‘Spanish’.

Gaskoin reunited smaller collections of letters with the court papers and exhibits in HCA 32, but died before finishing his work. These papers were then boxed and described by the first letter of the ships’ names – ‘Ships beginning M’.

We started work on the whole archive in 2012, trying to pour at least the names of ships for all wars into our catalogue, Discovery. For this we used the many existing registers or indexes created by the court. For the Austrian War, we used instead the card index of ships created by Gaskoin (kept in our ZBOX series of abandoned editorial projects). This was converted into a spreadsheet to give each ship a reference, and was used by our Collection Care volunteers, working with me and conservator Jamie Beveridge, to identify ship collections. They cleaned off soot and dirt, brought related papers together, and repacked them, ship by ship.

In 2018, we started the serious work of creating a more detailed catalogue, to adequately identify each document for digitisation. We created an internal numbering system that identified the court papers (CP1 etc) and the papers found on each ship (SP 1 etc) – re-using any numbering system applied by the court, as these numbers were also used in the abstracts and translations created for the court.

We decided to leave detailed descriptions of letters etc to the Oldenburg side of the project: it was impossible for us to do otherwise, both for the level of work needed, and because we only had 8,000 characters to describe each ship collection.

This was because the catalogue’s seven-level hierarchy was reduced for these ships to just one level – the bottom level of item. Information about the court, the war and the box occupied the upper levels, used for the creator history. But the Prize Papers are ephemeral collections, not really created by the court and brought together only by the triple occurrences of papers being physically on a ship, the ship being captured, and the processes of the court to legitimate the capture.

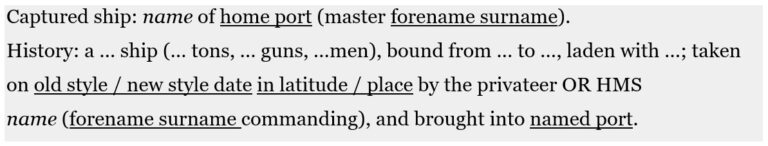

We decided that these three occurrences all hinged on the point of capture, and so we needed to describe the capture history of each ship. These histories were uncovered from the examinations of the captured crew or from ship’s or court papers. We created a standard descriptive template, designed to provide enough information for multiple points of entry for research, whether into trade, or commodities, or ports, or naval careers, or fights, or privateering, or the effect on a local economy of so many captured ships being brought in to e.g. Plymouth (naval captures) or Dartmouth (privateer captures). Searching in Discovery can bring together cases of interest in quite a different way than the brilliant filtering of detailed data on each document in the Prize Papers Portal.

Don’t forget that any search in Discovery can be downloaded, using “Export results”: with structured data, a download can be converted to columns in Excel for analysis.

Our basic capture template

This could be expanded to cover many eventualities, such as ships being taken in fight; or retaken, sometimes up to three times.

At this point old style dates (used by the British) were 11 days behind new style, used in Europe. We give both for the date of capture if possible: dates in court papers are given in British old style, whereas dates in ships papers are usually new style.

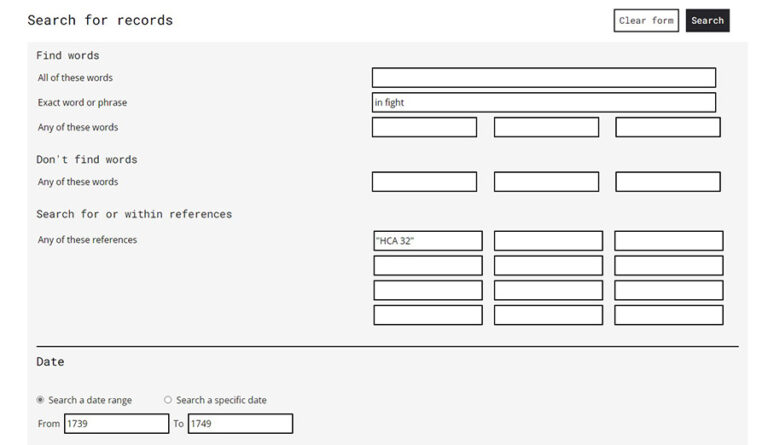

Searchability and findability in a structured description

One of the main benefits of Discovery is the flexibility of searching. We wanted to make the most of being able to search by phrase, and so used set phrases within the capture history. The best way to replicate this kind of search is to use Advanced search, with dates set and Exact word or phrase, or to put the phrase or phrases in “quotation marks”.

The following examples of capture histories do not show the reference: this is to encourage you to try a search in Discovery yourself!

• Captured ship: Jeune Marie previously the Notre Dame de Fallance (master Gabriel Dufaux).

History: a French privateer (200 tons, 14 guns, 62 men), bound from Martinique to Bordeaux, laden with sugar, coffee and cotton; taken in fight on 24 May / 4 June 1745 at latitude 45° 5′ by the privateers Boscawen (George Walker commanding) and Sheerness (John Furnell commanding): the ship sank, but the master and about 30 crew were brought into Bristol. [105 ships put up a fight – perhaps this example shows why more did not]

• Captured ship: Le Mentor (master Jacques Combetes or Combet or Combett).

History: a French merchant ship (300 tons, 12 guns, 36 men), bound from Cap François, Saint Domingue to Bordeaux, laden with sugar, coffee, indigo and hides; taken on 14/25 October 1744 at latitude 45° by HMS Jersey (Charles Harvey commanding), and brought into Plymouth. [572 ships were taken or retaken by naval vessels]

• Captured ship: La Légère (master Jean Harismendy).

History: a French ship (80 tons, 4 guns, 20 men), bound from Bordeaux to Quebec and then Martinique, laden with wine, brandy, soap, cordage and bale goods; taken on 18/29 May 1746 near the Isle Dieu by the privateers Success (Philip Winter commanding) and Squirrel (Nicholas Couteur commanding), and brought into Jersey. [790 ships were taken or by British privateers, of which 107 were by British privateers working together]

• Captured ship: Vizcanio or Vizcaino or Biscaina or Vizcanio Santa Clara of San Sebastian (master Antonio Lafarque, later Juan Girard or Giral).

History: a Spanish privateer (90 tons, 12 guns, 119 men), bound from San Sebastian on a cruise; taken on 31 May / 11 June 1741 off Cape Machada (Galicia) by HMS Rupert (John Ambrose commanding), and brought into the River Thames. [181 foreign privateers were taken while hunting for British ships]

• Captured ship: Two Brothers of London (master Rayson Grindall).

History: an English merchant ship (60 tons, 18 men), bound from Maryland to London, laden with tobacco and iron; taken on 6/17 May 1746 in latitude 49°N by the Spanish privateer La Brigani Van Joseph, retaken on 12/23 May 1746 in latitude 44°N by the privateer Blandford (George Stonehouse commanding) and brought into Bristol. [107 taken or retaken ships were brought into Bristol: for the 81 ships moved from the first port to another, perhaps for a better market, try “brought first into”]

Place names

Place names are given in modernised versions of the old name often as used by the British, not the modern name – so Isle Dieu rather than Île d’Yeu; Isle de France (often with Mauritius given as well); Saint Domingue, not Haiti. We do have an inconsistency here: every other such place is given as St – St Eustatius, St Lucia, St Helena – but Saint Domingue was so important within the global colonial economy, and within the trade in people, that we used the fuller obsolete name. Many thousands of the letters on board ships were being sent from or to Saint Domingue.

Trade routes and cargoes

Not everything is searchable by phrase: cargoes are mostly just listed as they are mentioned. Within Europe, the standard produce traded were oil, fruit and wine from the south, and timber, fish, grain and textiles from the north. Colonial produce from the Caribbean such as coffee and sugar, poured out across Europe via French ports in vast quantity; as well as indigo, dye woods, drugs etc.

Going over to the Caribbean were two major trades: the two-way provisions trade from Europe and North America, and the triangle trade of European goods to buy enslaved people from West Africa, for forced labour in the Caribbean plantations. We identified two major French slave trading archives, taken from ships on their way back to France: the Abraham of Nantes and the papers of the Providence of Nantes, sent back on board the Postillon of Nantes. These give details of individual (but unnamed) people being bought along the African coast over several months, and the goods used to buy them.

• Captured ship: Hannah of London (master William Fowler, Joseph Dominguez after the first capture and James Oswald after the second capture).

History: an English merchant ship [in the slave trade ?] (250 tons, 10 guns, 24 men), bound from Jamaica to London, laden with sugar, rum, indigo, turtle shells, 20 elephant’s teeth [ivory], sarsaparilla, logwood, hides, and bale goods; taken on 14/25 June 1744 near Kinsale by the Spanish privateer Nostra Senora del Carmen (Catano Blanco commanding), retaken on 17/28 June 1744 at latitude 48°N, longitude 7°17’W by the English privateer Old Noll (James Powell commanding), and brought first into Cork, and then into Liverpool. [William Fowler complained that his men were drunk and would not fight; he died shortly after arriving at Cork.]

Ivory was one major commodity brought from West Africa via the Caribbean to Europe. We catalogued this using the term elephants’ teeth, as used in the records, partly to make clear the ecological loss. We also took the view that any ship carrying elephants’ teeth was likely to be in the slave trade.

Complicated captures

Not all captures can fit into such a condensed description. Here’s a very complicated one:

• Captured ship: Notre Dame de la Deliverance or Nuestra Senora de la Delibranza of St Malo (master Pierre Litant).

History: a French merchant ship contracted as a Spanish register ship (300 tons, 22 guns, 60 men and 1 passenger) bound from Callao, Peru to [Cadiz], laden with $1,280,000 in silver, and cocoa, in company with the Marquis D’Antin and the Louis Erasme; the two latter ships (carrying $3,000,000 in silver plus cargo) were taken in fight on 10/24 July 1745 by the privateers Prince Frederick (James Talbot commanding) and Duke (Morecock commanding), but the Deliverance fled to take refuge in Louisbourg, not knowing it had been taken by the British a month before. Deliverance (in morning fog, and by the deception of the armed brigantine Boston Packet of Massachusetts (William Fletcher commanding, since deceased) acting on Fletcher’s initiative as a lure under French colours) was taken on 28 July/13 August 1745 off Cape Breton Island by HMS Sunderland (John Brett commanding), and HMS Chester (Philip Durell commanding), both coming out from Louisbourg under French colours, and was brought into Louisbourg, where the ship was broken up in search of the treasure.

Several naval ships and some of the captors’ crew also under the command of Admiral Peter Warren remained behind to guard Louisbourg from the expected French squadron. These ships, HMS Canterbury (Daniel Hore), HMS Vigilant (William Holburne), HMS Princess Mary (Henry Edwards), HMS Mermaid (Warwick Calmady), HMS Lark (John Wickham) and several locally-commissioned ships including the Boston Packet, the Massachusetts Frigate, Hector, Sylvester, Fame and Caesar, also claimed as joint captors.

The overview Wikipedia entry on the War of Austrian Succession focuses mostly on the many land campaigns across Europe, and in the Americas and India. For the wars at sea, it describes naval pitched battles and campaigns, George Anson’s expedition to attack the Spanish in the Pacific, and the failed French attempts to support the Jacobite rising. These all appear in the Prize Papers of the Austrian Succession – try a search on ‘battle’, or ‘Anson’ or ‘Jacobite’, restricted by date to 1739-1748, and by series to HCA 32 and HCA 30. But we hope you can see that there were many more confrontations at sea than these, some ending in death, some in long years of suffering as prisoners of war, and some in considerable profit for the captors.