It is always comforting to realise we’re not the only ones dealing with trivial issues which take ages to resolve. While working on our interactive First World War map, my team and I had to decide whether we should use the modern spelling of country names or the old one (Serbia/Servia, Romania/Roumania, Sudan/Soudan…) and then convince others that we were right. It was therefore quite heartwarming to find out that the Foreign Office and the Colonial Office had been squabbling over a very similar matter almost 100 years ago.

In November 1926, the Estonians asked the British Government whether they could possibly be so kind as to stop spelling them with an ‘h’. The Northern Department of the Foreign Office noted that they didn’t feel very strongly about it because it seemed ‘silly to risk annoying the Esthonians for the sake of a letter’ (FO 370/217). With Iraq, however, it was an entirely different matter.

In August 1922, the newly established Permanent Committee on Geographical Names for British Official Use ruled that the correct spelling for Iraq was ‘Iraq. Luckily for the Colonial Office, this was the way they had always spelt it. Unluckily for the Foreign Office, they had until then favoured Irak (FO 371/10119).

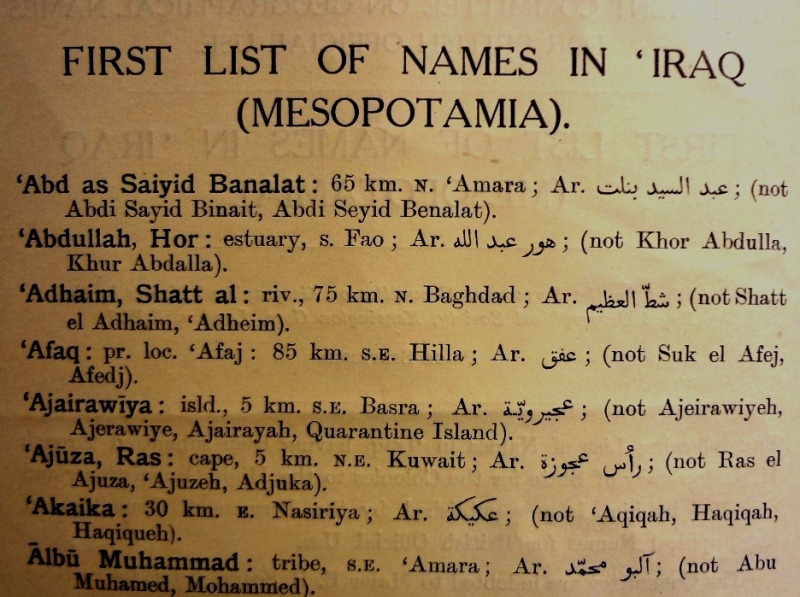

First list of names in Iraq, Permanent Committee on Geographical Names, August 1922 (catalogue reference: FO 371/10119)

The Foreign Office did have a representative on the Committee, but thought its rules weren’t binding and that there was no reason why they should change their spelling habits. In 1924, the Colonial Office wrote to ‘invite the attention of Mr Secretary Ramsay MacDonald’ to the fact that ‘the correct spelling of the word was “Iraq”, and not “Irak”’ (FO 371/10119).

Stephen Gaselee, the Librarian and Keeper of the Papers at the Foreign Office, was (somewhat disloyally) in favour of the spelling Iraq, and explained:

‘I am in favour of the spelling Iraq in spite of the unfamiliarity in English of a q not followed by a u. There are two letters in Arabic having more or less a k sound, one more explosive than the other; and it seems convenient to allot q to one of them, the more explosive of the two.’

Gaselee was, of course, quite right. The sound we now transcribe as q is almost impossible to pronounce correctly for a non-native speaker – I certainly can’t! It is a sort of k sound coming from the very back of the throat, which most people end up pronouncing as a normal k. Yet, the difference is not without importance – for instance, ‘kalb’ means ‘dog’ while ‘qalb’ means ‘heart’.

Gaselee was right, but he was a scholar and, as a lot of us can testify, purely scholarly views are rarely popular. Another Foreign Office Official commented:

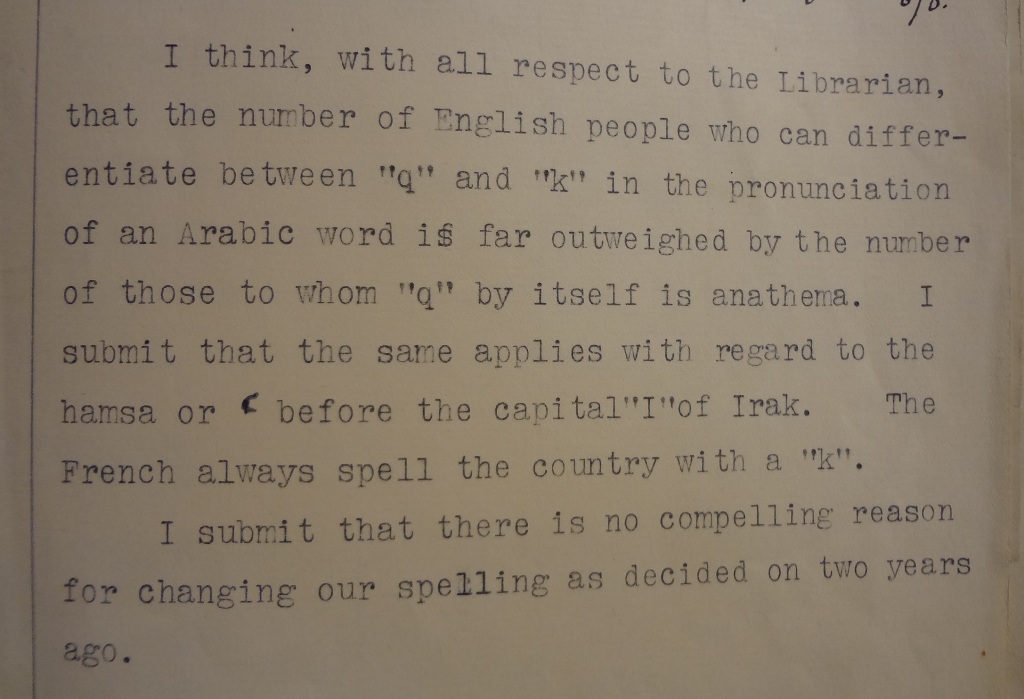

‘I think, with all respect to the Librarian, that the number of English people who can differentiate between “q” and “k” in the pronunciation of an Arabic word is far outweighed by the number of those for whom “q” by itself is anathema.’

Foreign Office Minute, September 1924 (catalogue reference: FO 371/10119)

Not only the Colonial Office wanted to spell the name with a final q, but they also insisted (shock and horror!) on an apostrophe before the I at the beginning of the word. Sharing the general opinion that using q was ‘perfectly absurd,’ MacDonald replied that he preferred that ‘the spelling of the name of the mandated territory administered through HM High Commission at Bagdad should be Irak rather than ‘Iraq.’ As a result, the Foreign Office continued to issue visas to visit Irak while the Colonial Office issued theirs to Iraq.

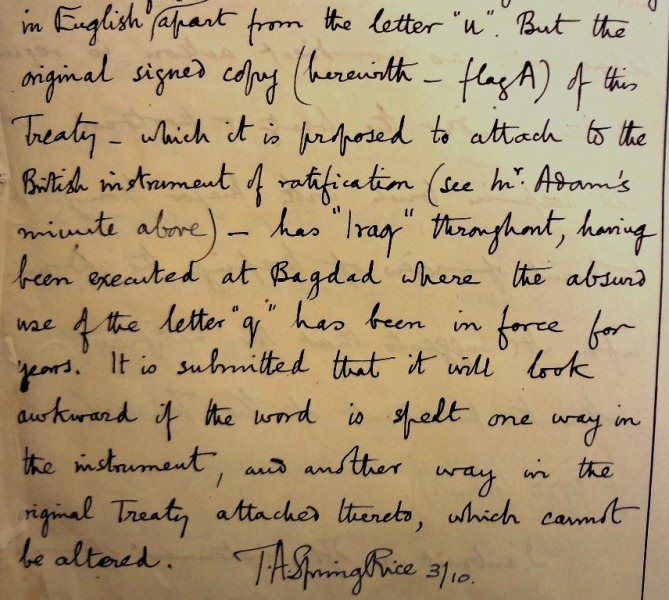

Similarly, when the Treaty of Alliance between Great Britain and Iraq, signed in 1922, was finally ratified in 1924, Spring Rice, from the Eastern Department, complained at great length about the fact that the treaty had ‘“Iraq” throughout, having been executed at Bagdad where the absurd use of the letter “q” has been in force for years.’ Incidentally, the Colonial Office also claimed the capital should be spelt Baghdad, to reflect the rather peculiar gh sound (a roll in the back of the throat, not unlike the Parisian r) (FO 371/10096).

Minute by T. A. Spring Rice, 03/10/1924 (catalogue reference: FO 371/10096)

The question was raised again in February 1925 when the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Leo Amery, wrote to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Austen Chamberlain, about what he described as ‘a rather trivial question’ and explained he had found that ‘our respective Departments are divided on the subject, both in theory and in practice, and it seems desirable that we should get the point settled’ (FO 371/10838).

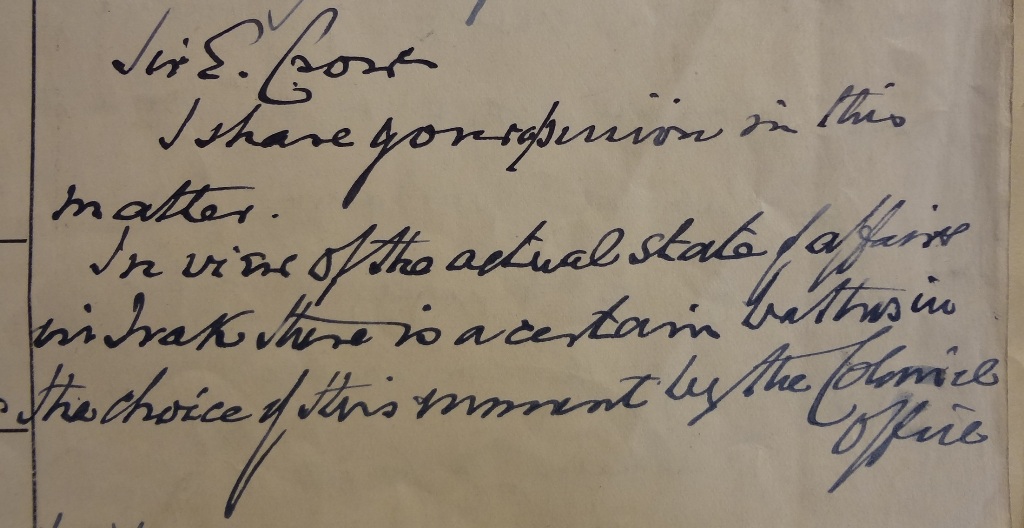

The Eastern Department’s reaction to this request was probably more violent than necessary, ranging from ‘I decline to take any interest in this foolery. The C.O. seems to have very little to do’ to ‘in view of the state of political affairs in Irak there is a certain bathos in the choice of this moment by the Colonial Office.’

Eastern Department’s reaction, 26/2/1925 (catalogue reference: FO 371/10838)

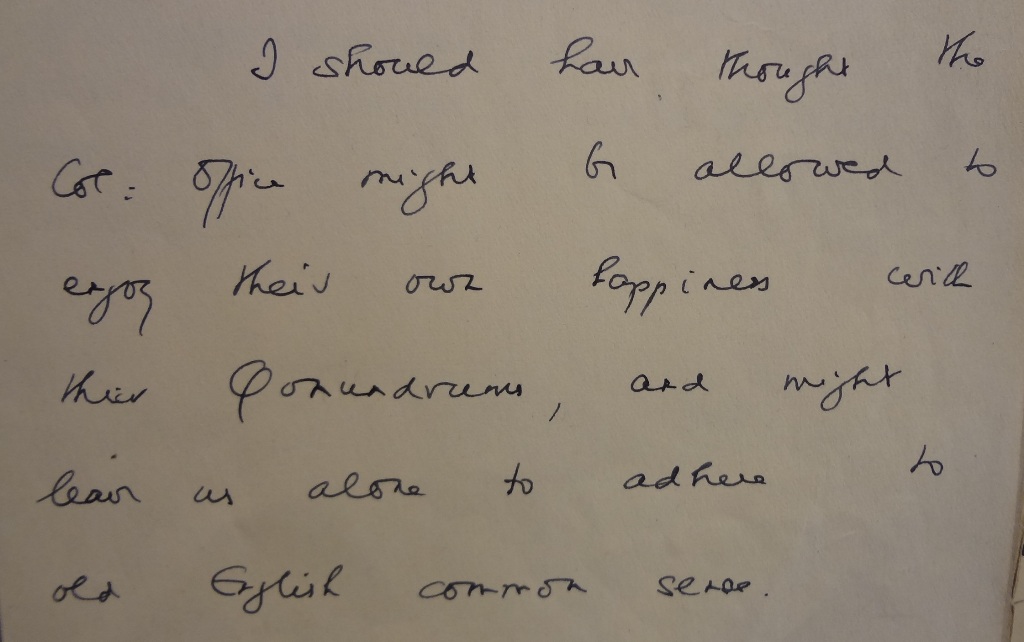

A member of the Eastern Department, Carson, was particularly vocal and wrote a two-page long comment. He insisted that ‘we should not adopt the altogether ridiculous fad of the India and Colonial Office’, noted that ‘the resulting jargon is offensive to one’s sense of English and altogether confusing’ as it would entail, amongst other things, writing Qut instead of Kut to refer to the infamous 1915-1916 siege of Kut, and concluded:

‘I should have thought the Col[onial] Office might be allowed to enjoy their own happiness with their Qonundrums, and might leave us alone to adhere to old English common sense’ (FO 371/10838).

This was a rather passionate reaction to a possibly insignificant issue but, as a result, Chamberlain sent his regrets and wrote at the beginning of March that he wasn’t ‘prepared to depart from the procedure adopted by his predecessors as spelling the word as given above [Irak] in accordance with long-standing custom’. This seemed to be it (FO 371/10838).

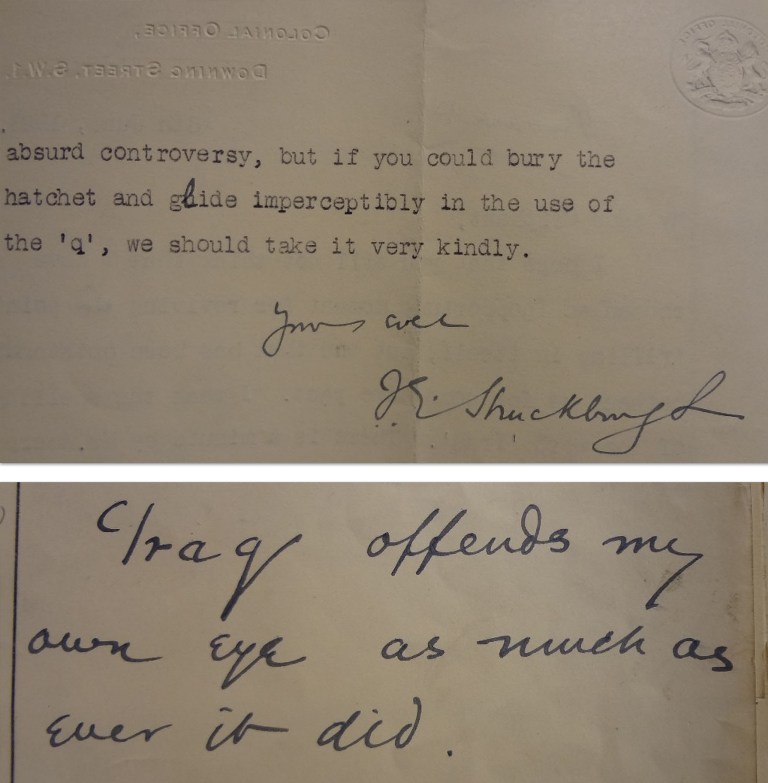

On 8 June 1926, however, Sir John Shuckburgh, the Assistant Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies (Middle East), wrote to Lancelot Oliphant, the Head of the Eastern Department, to discuss ‘a point, trifling in itself, but one that has been outstanding between us for some time past’. He stated that Tyrell, the Permanent Under-Secretary, had talked to Amery and accepted the Colonial Office’s way of spelling Iraq, and he expressed surprise at the continued use of the final k. He concluded: ‘if you could bury the hatchet and glide imperceptibly in the use of the ‘q’, we should take it very kindly’ (FO 371/11479). Oliphant noted: ‘Iraq offends my own eye as ever it did,’ and turned to Tyrell for guidance. Tyrell stated: ‘let us adopt Sir J. Shuckburgh’s advice and hint and drop this controversy.’ He added: ‘No answer’ (FO 371/11479).

The Foreign Office finally relented. On 15 July 1926, Gaselee wrote to John Reynolds, of the Permanent Committee on Geographical Names: ‘Whereas the Foreign Office has in the past written Irak we propose in the future to write Iraq’. Probably feeling very smug, Reynolds replied: ‘strictly speaking it should be preceded by the inverted comma, ‘IRĀQ.’ This was to much to ask, and the reply came promptly: ‘we are not prepared to use the inverted comma or apostrophe before or after the I, nor the long mark over the A.’ There’s only that much a Foreign Office official can take (FO 371/11479).

I am confident we will all agree that Iraq by any other name would smell and look as sweet, and that it was a trivial question. A trivial question, perhaps, but one that kept civil servants occupied for almost two years. In the words of Carson in February 1925, ‘I call it lunacy’!

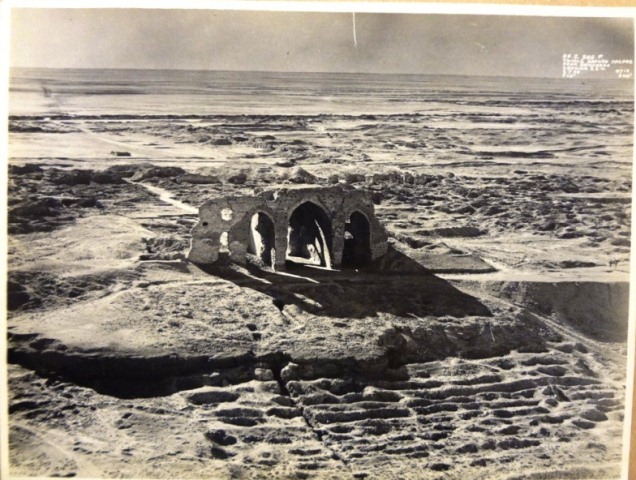

Beit el-Khalifa, Iraq, during the Second World War (catalogue reference: OS 1/384)

[…] It is always comforting to realise we’re not the only ones dealing with trivial issues which take ages to resolve. While working on our interactive First World War map, my… Go to Source […]

Post of the year.

The spelling of place name should generally, as far as an archive is concerned, be the original spelling and with the new spelling in square brackets, i.e. Servia [Serbia] and there are many examples of mis-spelling in Discovery (Holland, which has been The Netherlands since the late 17th Century, places like Arnhem are not in the provinces of Holland) and Scotland not North Britain. The fact that the Foreign Office spent so much time debating the spellings is not surprising, but in my view over-cautious.

Remarkable!!