Very few things are actually better than the opening of a new archaeological museum. In Cairo, in 1925-26, it almost happened.

On 24 November 1924, British Egyptologist Alan Gardiner wrote to the Prime Minister and stated: ‘the Cairo Museum is at once the richest and the worst managed in the world’. He wasn’t way off the mark. The Cairo Museum had been built just over 20 years before, in 1902, and most archaeologists agreed it was too small for its purpose (FO 141/487).

On 3 February 1925, James Breasted, of the Chicago Oriental Institute, wrote to the High Commissioner, Lord Allenby. He was sending a memorandum

‘setting forth the present serious conditions in the Cairo Museum, and suggesting a constructive plan of cooperation with the Egyptians for the future welfare of their priceless inheritance from the past’ (FO 141/629).

Breasted didn’t have a kind word to spare for the Museum. According to him it was an ‘unsafe repository for the priceless collections which it [housed]’. ‘Faulty in construction’, with a ‘leaky roof’ and ‘a basement below high water level’, it was also ‘badly lighted’ and completely outdated, and lacked ‘modern facilities’ such as working rooms, labs or magazines.

For some reason, Breasted particularly disliked the building itself and described it as

‘a specimen of cheap and tawdry architecture plastered on the outside with stucco imitation of ashlar masonry, which falls off in numerous huge and ugly patches’ (FO 141/629).

The only solution, Breasted wrote, was to use ‘a large gift of money from private sources in America’ to build a new state of the art museum ‘with no stucco facing’, which would incorporate all the modern facilities an archaeologist could desire. Breasted understood the plan was ‘beset with difficulties’, but thought it would be ‘an impressive gesture of friendship from the new West to the ancient East’.

He explained that an ‘endowment of two million dollars, and if necessary more’ could be established to maintain the new museum, and proposed the appointment of an Antiquities Commission to hold everything in trust. It just so happened, Breasted added, that John D. Rockefeller Jr. had agreed to fund the project, and that they had the perfect site in mind: the Kasr-el-Nil barracks, very close to the current museum, on the banks of the Nile (FO 141/629).

Part of a city plan of Cairo showing the Museum and the Kasr-el-Nil barracks, 1914 (catalogue reference: MFQ 1/1379/59)

The project was at very early stages, and still secret. Breasted was consulting the British government for two main reasons. First, Britain still had considerable influence in Egypt despite the independence it had unilaterally bestowed upon the country in 1922; secondly, the troops of the British Army of Occupation, which had invaded Egypt in 1882, were billeted in the Kasr-el-Nil barracks, and Breasted needed them to evacuate.

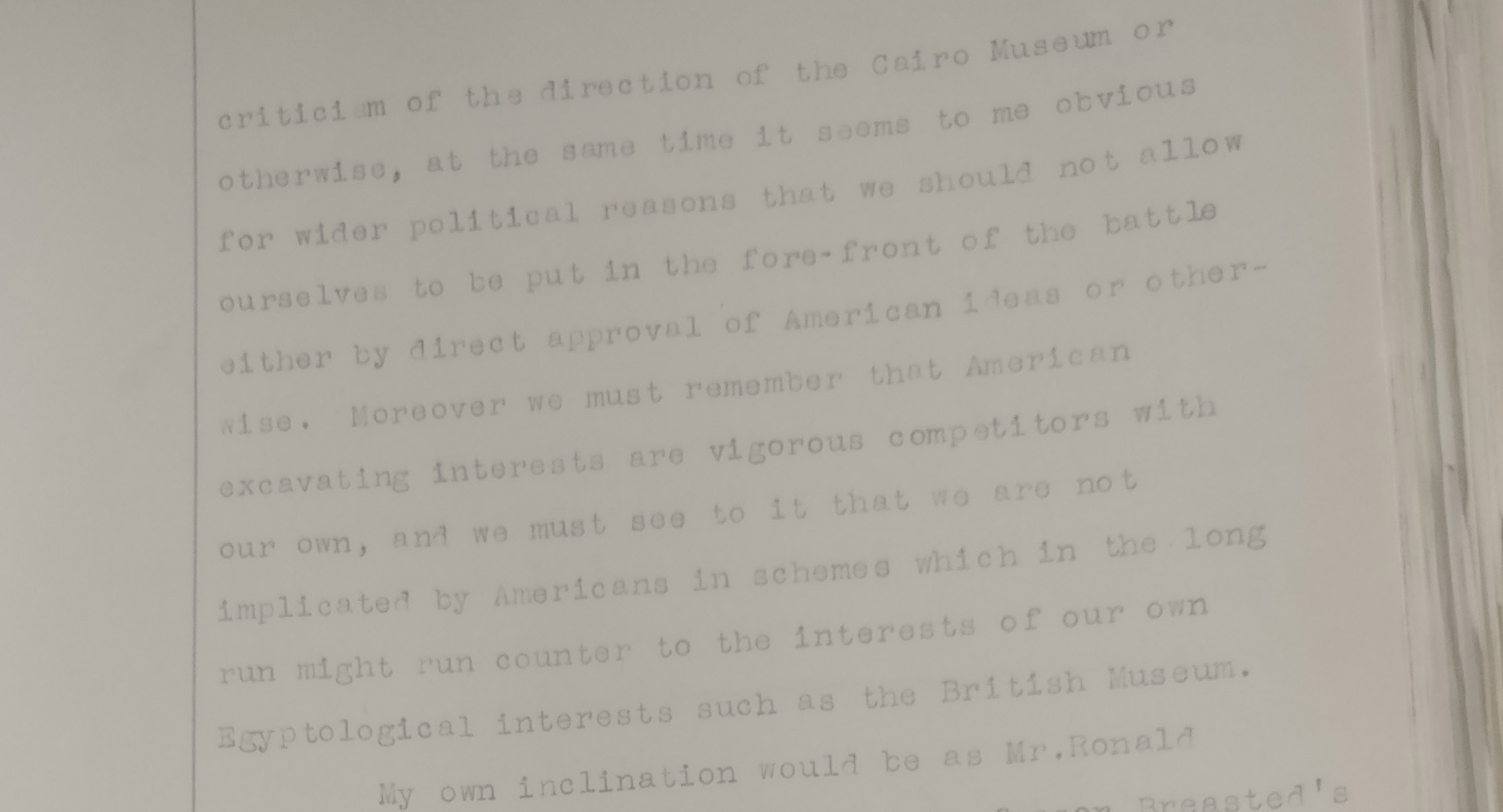

Lord Allenby was rather sympathetic to the idea, but at the Foreign Office some of his colleagues were less enthusiastic. They found the project vaguely appealing, but thought it was full of potential pitfalls and that the Americans would have a hard time negotiating with the French and the Egyptians. The Private Secretary, Sir Walford Selby, summarised it all very well. He agreed that the Antiquities Service was a ‘crying scandal’, but that a great deal of caution should be exercised:

‘it seems to me obvious for wider political reasons, that we should not allow ourselves to be put in the for-front of the battle (…). Moreover we must remember that American excavating interests are vigorous competitors with our own’ (FO 371/10897).

The Foreign Office decided to turn to the expert and to consult Sir Frederic Kenyon, the Director of the British Museum. On 4 March, Kenyon sent a note on the project which, he thought, was a great idea, mostly because it could help to get rid of the French.

The 1904 Anglo-French Declaration respecting Egypt and Morocco, better known as the Entente Cordiale, stipulated that ‘the post of Director-General of Antiquities in Egypt shall continue, as in the past, to be entrusted to a French savant’. France was very jealous of her archaeological rights, and the Director-General of the Antiquities Service, Pierre Lacau, wasn’t an easy man to deal with.

Kenyon concluded:

‘it would be a grievous mistake not to take this opportunity to terminate, at the earliest convenient date, the present French monopoly of the direction of the Service. It has not worked well; it has no foundation in reason’ (FO 141/629).

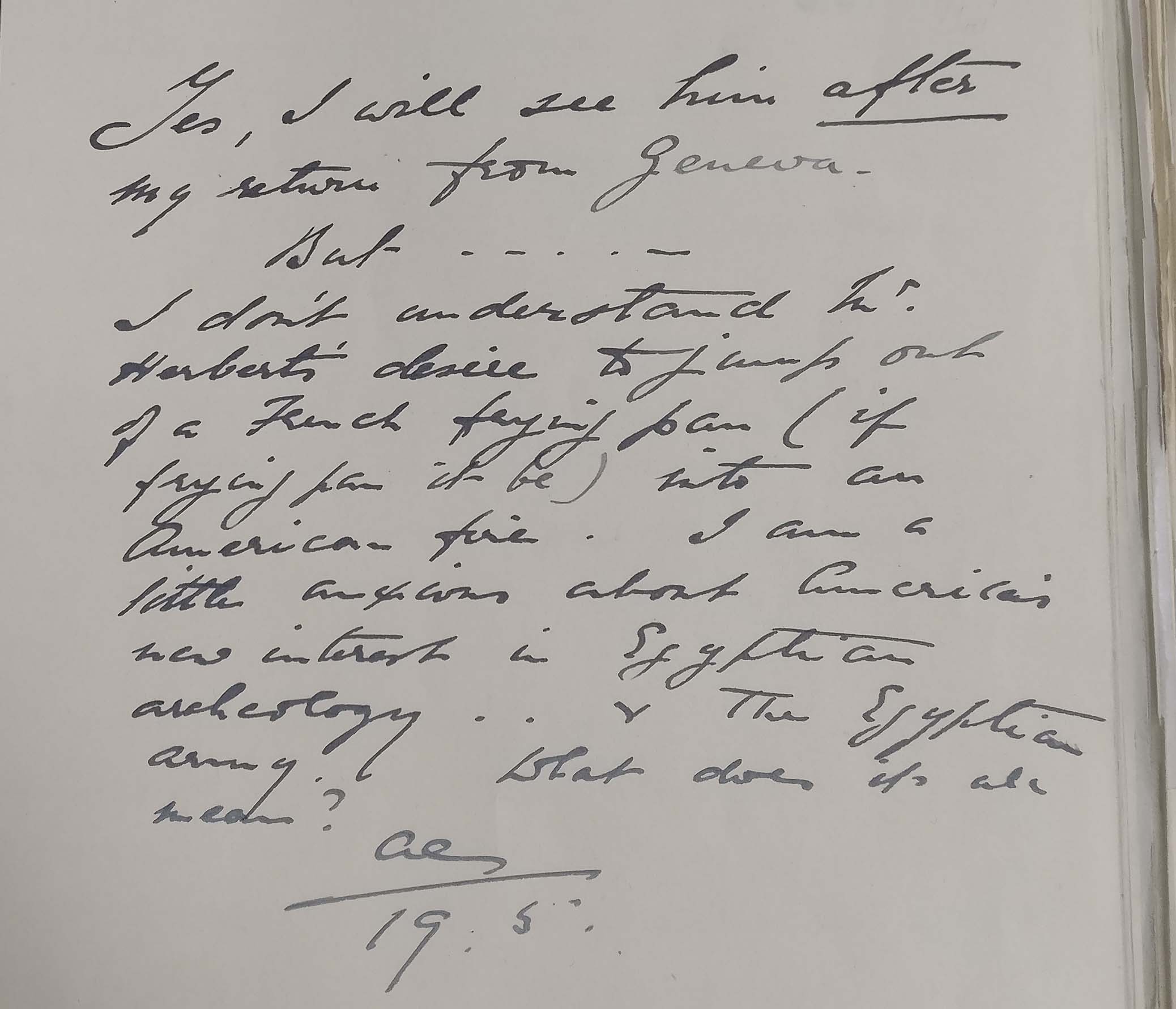

In the Egyptian Department at the Foreign Office, Mervyn Herbert and John Murray, thought it was worth a shot. Austen Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, disagreed. He wrote: ‘I don’t understand Mr Herbert’s desire to jump out of a French frying pan (if frying pan it be) into an American fire. I am a little anxious about America’s new interest in Egyptian archaeology’ (FO 371/10897).

It was eventually decided to lend cautious support to the project. The trick was not to support it too visibly so that it wouldn’t be perceived as linked to British political aims. The issue of the Kasr-el-Nil barracks proved a bit more complicated.

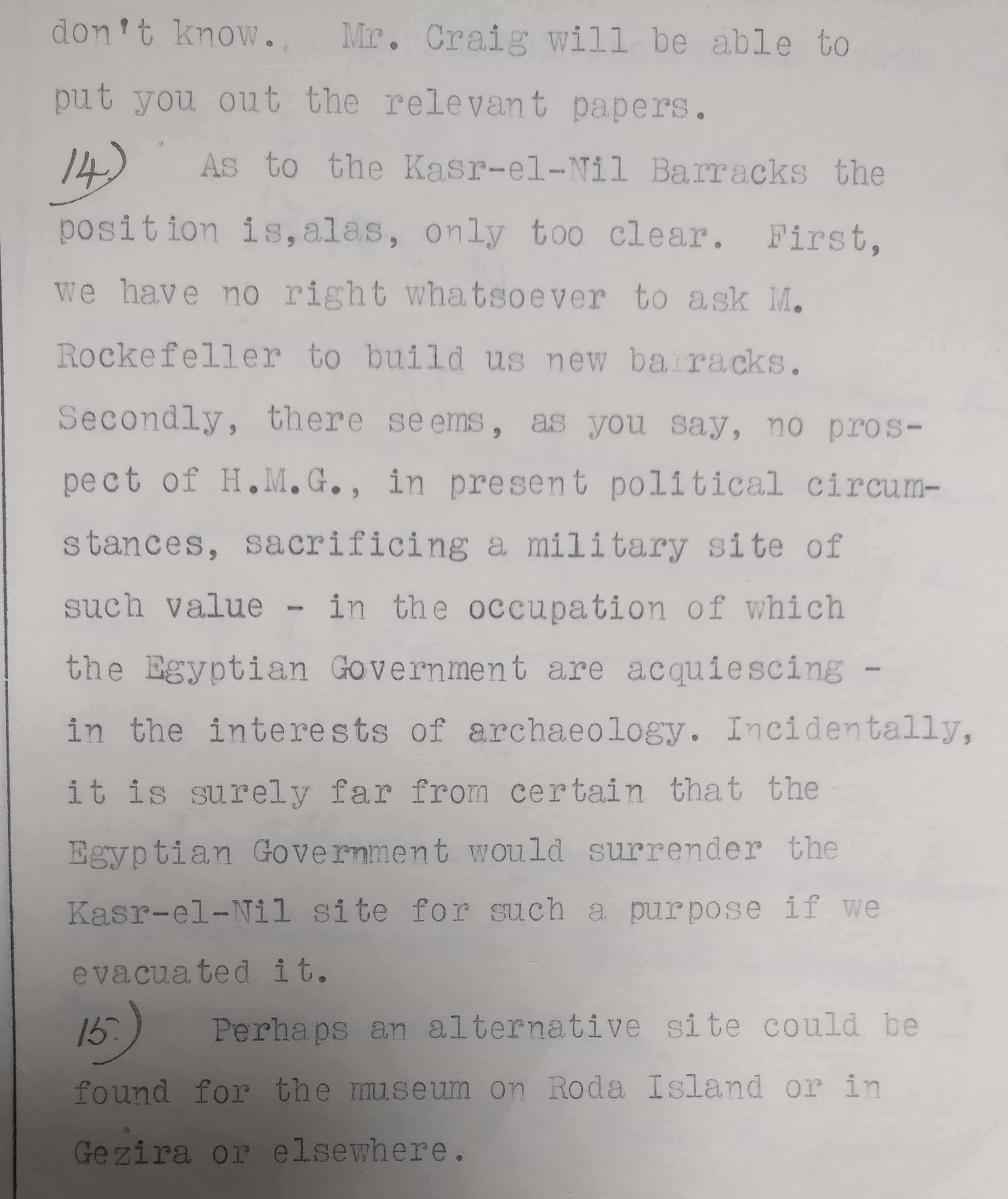

The barracks had been first occupied after the battle of Tell el-Kebir in 1882. The Foreign Office, especially Murray, thought the barracks could definitely be evacuated. If they were to be replaced by a museum, then Britain wouldn’t lose face and the evacuation would be considered as a gracious gesture. As Breasted had promised money would be found to rehouse the troops, Allenby thought it was a win-win situation. In February 1925 he wrote to Chamberlain: ‘no penny of expense will fall on anyone but the American donors’. The military authorities in Egypt, however, had different views.

The barracks controlled the bridges, Wiggin explained, and there could be no talk of ‘sacrificing a military site of such value (…) in the interests of archaeology’. He suggested alternative sites for the museum, Gezira or Roda Island, for instance, or the strip of public garden between the Sporting Club and the Nile (FO 141/629).

The General Officer Commanding the British troops in Egypt, General Haking, claimed that evacuating Kasr-el-Nil would ‘make a serious breach in his internal defence’, and new barracks would have to be built, which the Egyptians wouldn’t welcome. In November, Lloyd, who had replaced Allenby, informed Breasted that ‘if he [wanted] his scheme to proceed, he must provide an alternative site which [did] not involve the removal of troops from the Kasr-el-Nil barracks’ (FO 141/629).

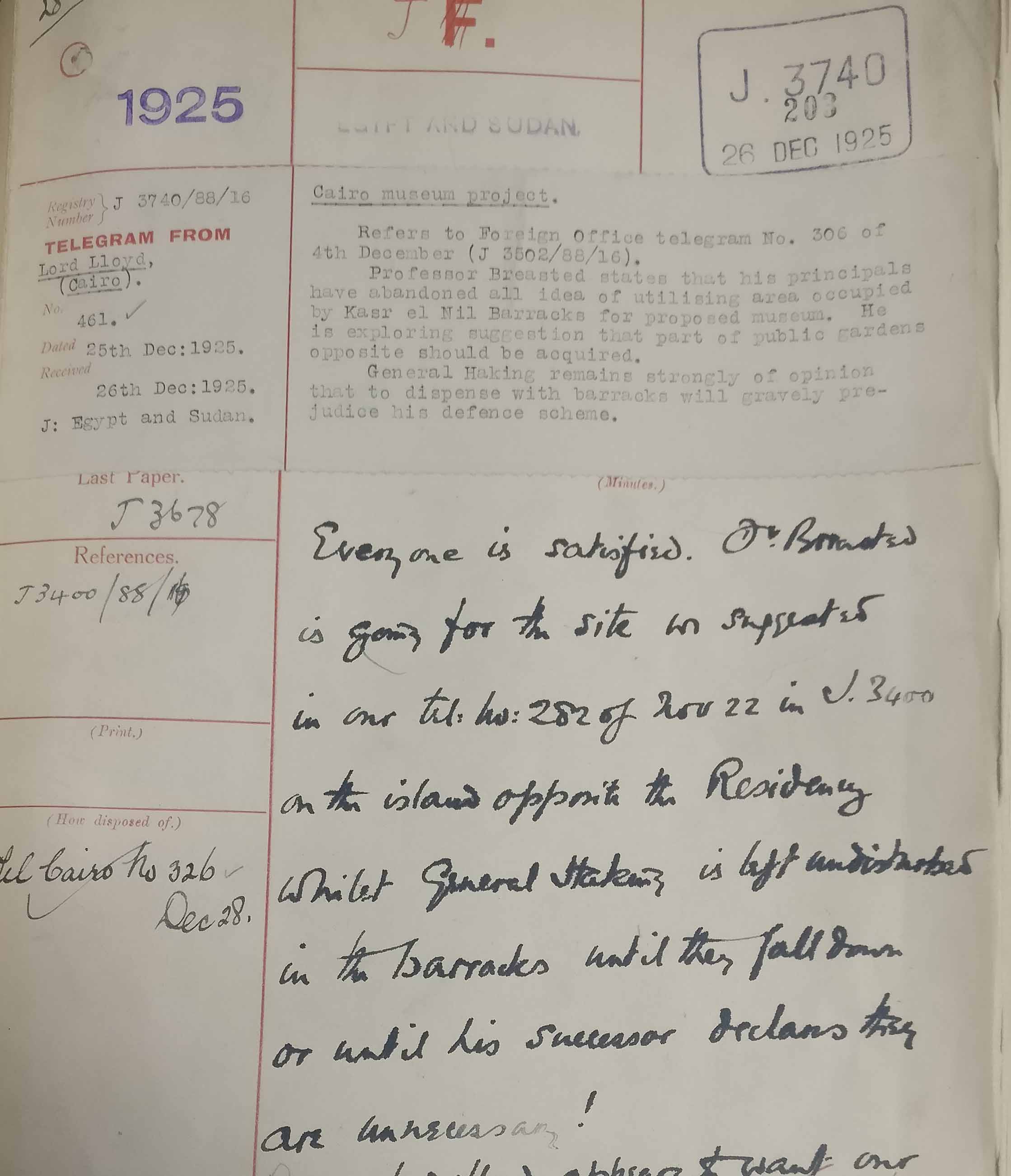

Rockefeller and Breasted, however, insisted on the Kasr-el-Nil site, and warned that the reasons given may have an ‘unfortunate effect’ on public opinion should they become known. They finally relented in December and Murray wrote: ‘everyone is satisfied. Dr Breasted is going for the site we suggested (…) on the island opposite the Residency whilst General Haking is left undisturbed in the barracks until they fall down or until his successor declares they are unnecessary!’ (FO 371/10897).

Breasted thought negotiating with the Egyptians would be a mere formality. He was very wrong. He presented the scheme to King Fuad on 4 January 1926, and tried to appeal to his nationalist pride. ‘The earliest of [Egypt’s] venerable monuments,’ he said, ‘were erected at a time when all Europe was still shrouded in darkness and savagery’. Rockefeller was offering ten million dollars to build ‘the most magnificent museum building in the world’.

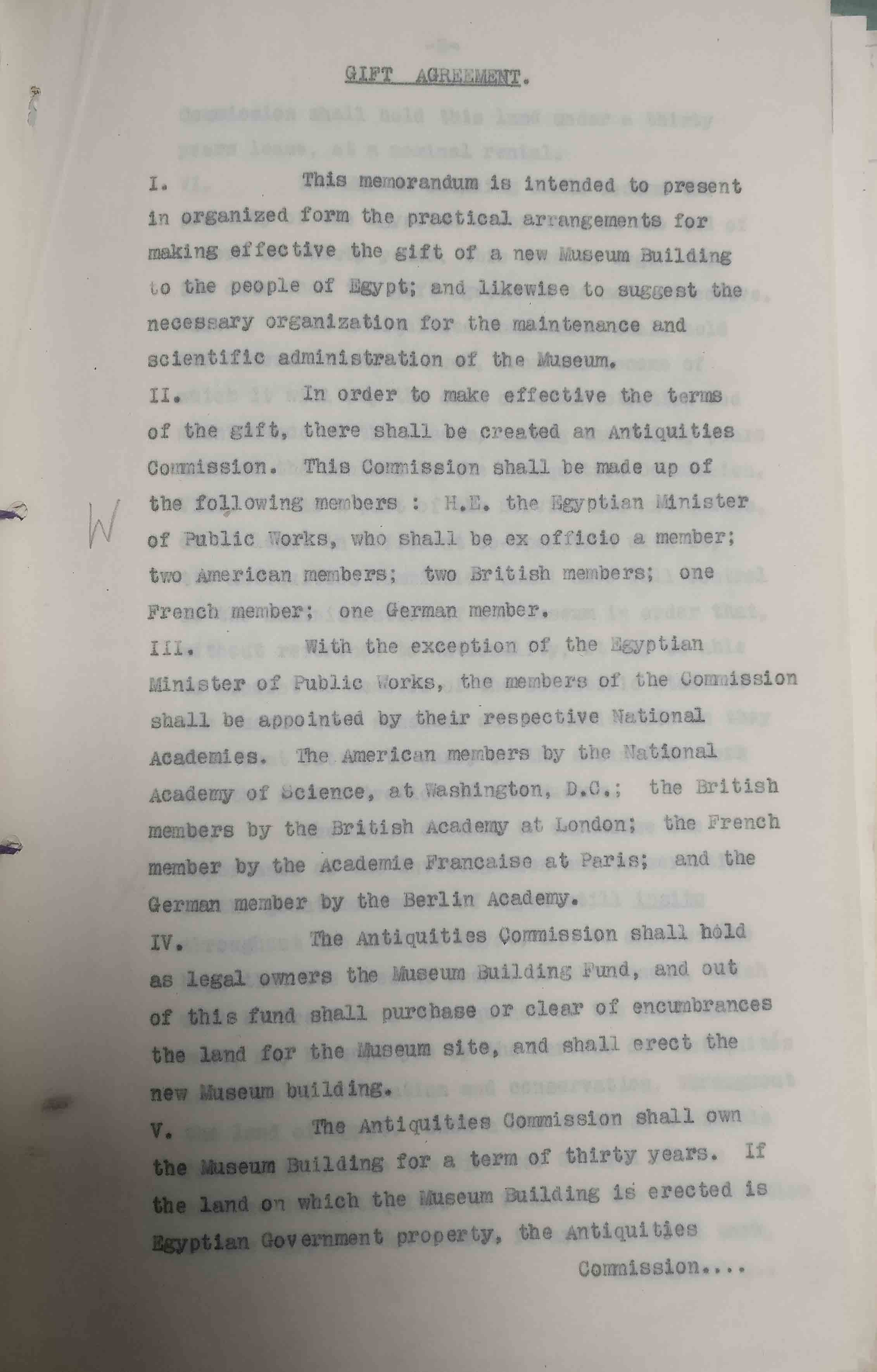

This ‘gift’ came with a price: the museum would effectively be under the control of an Antiquities Commission composed of the Egyptian Minister of Public Works (ex-officio), two British archaeologists, two Americans, one Frenchman, and one German, all appointed by the National Academies. They would own the Fund and oversee the building of the new museum for 30 years, after which it would become the property of the Egyptian Government.

Rockefeller and Breasted argued that it had taken America about 30 years to develop a new generation of Egyptologists, and they thought the same would be true of Egypt.

As the Commission would have ‘full control of the administration of the Museum’, the King wasn’t impressed. The Egyptians felt that if they accepted Rockefeller’s ‘gift’, they would be acknowledging their incapacity to run their own antiquities, an acknowledgement that could be used against them in other respects. They decided to stall the negotiations.

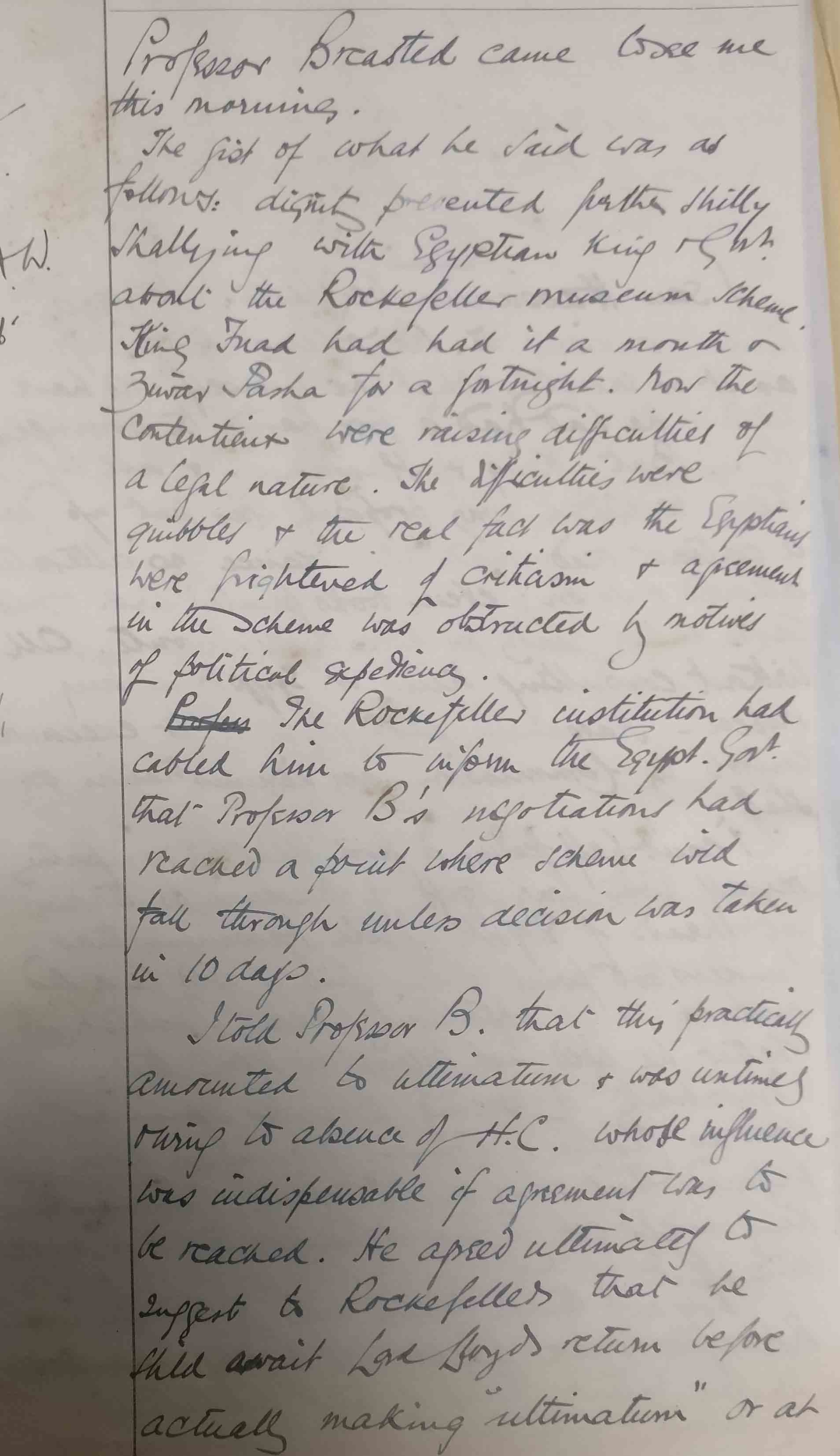

Having received no answer by the beginning of February, Breasted met with Wiggin and said that ‘dignity prevented further dhilly dhallying with the Egyptian King and Government about the Rockefeller Museum scheme’. In what amounted to an ultimatum, Breasted gave the Egyptians ten days to give an answer (FO 141/629).

The Egyptian Government kept stalling. They were keen to see such an investment made in their country, but couldn’t sign the Gift Agreement as it stood. They weren’t particularly opposed to the museum itself (even though it would have been a very tangible and visible symbol of foreign influence), but the proposed Commission was a different matter. The commission would run the museum with no interference from the Government, and therefore increase foreign control over Egyptian archaeology.

On 14 February, to quell rumours, Breasted made the scheme public. Rockefeller denied it all, which was probably indicative of what was about to happen.

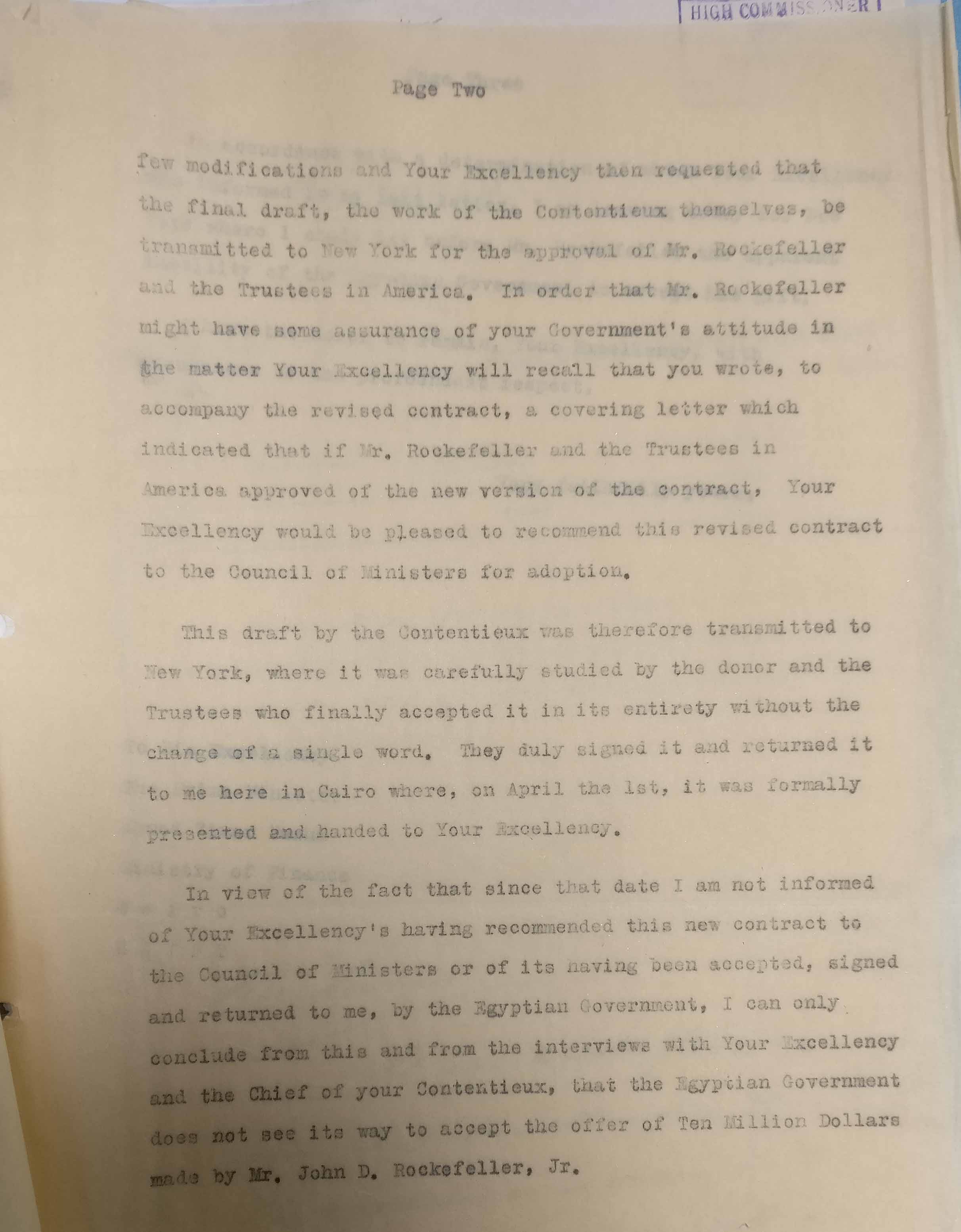

On 8 April 1926, Breasted wrote to the Egyptian Prime Minister, Ahmed Ziwar Pasha. The trustees in the US and the Egyptian legal Advisers had finally agreed on the wording of a contract on 1 April, but the Prime Minister had not yet fulfilled his promise to take it to the Council of Ministers for approval. He wrote:

‘I can only conclude, from this and from the interviews with your Excellency and the Chief of your Contentieux, that the Egyptian Government does not see its way to accept the offer of Ten Million Dollars made by Mr. John D. Rockefeller Jr.’ (FO 141/629).

Ziwar Pasha ignored the letter. Rockefeller wrote to King Fuad on 27 April:

‘Under these circumstances and in order to relieve the Egyptian Government of embarrassment, the proposal which I had the honor of presenting to your Majesty and the Egyptian Government is now withdrawn’ (FO 141/629).

- John D. Rockefeller Jr. to King Fuad, 27 April 1926 (catalogue reference: FO 141/629)

- John D. Rockefeller Jr. to King Fuad, 27 April 1926 (catalogue reference: FO 141/629)

The Rockefeller Cairo Museum was never built. The Americans and the British blamed the failure of the scheme on Egyptian intransigence, but it is quite clear Breasted had not fully appreciated political changes in Egypt. The discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922 had placed antiquities at the centre of national pride, and the scheme was very colonial in its approach. At a time when nationalism was on the rise, it had virtually no chance to succeed.

The Egyptian Museum still stands today, in all its pink and stucco glory… While it will always remain one of my favourite museums in the world, Breasted and his contemporaries did perhaps have a point. As I write, a new museum, the Grand Egyptian Museum, is being built in Giza, on the Pyramids Plateau.

In a way it’s comforting to know that the state of the museum is not a decline due to modern political upheavals or lack of interest, but rather, a series of design flaws that perhaps have ever been present! I find a visit to that museum deeply disturbing, given not only the lack of atmospheric control, but the way that visitors are able to touch so much of the material on display.

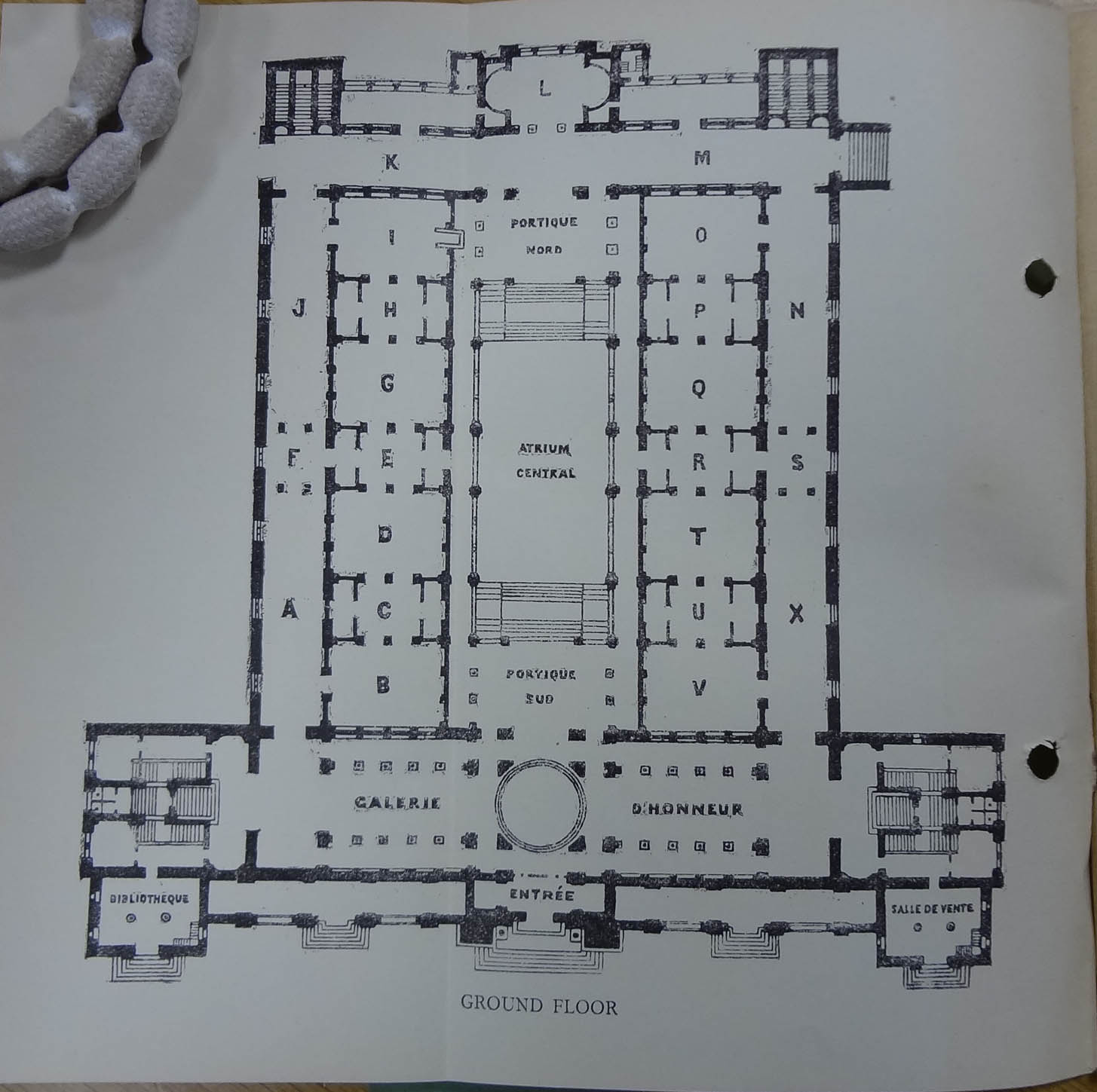

The detailed architectural plans and artist’s conception for Breasted’s museum are fabulous to behold, even eye-popping in their scale and grandeur. A printed copy, bound in a large elegant folio was (maybe still is?), to my knowledge, located in the University of Chicago Epigraphic Survey Library at Chicago House in Luxor. As I recall, it was a brilliant design with a series of open courts, arcades and loges, one court leading into another. Sadly, after so much resentment by Egyptian, French and British authorities–especially due to jealousy over burgeoning American archaeological activities (even suggested in contemporary sentiments above), Rockefeller was forced to withdraw his offer. British objections were political, to keep the America from becoming influential in the area. Through the Sykes-Picot Treaty, Britain and France were carving up the Middle East, while American policies (as first espoused in Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points and by the latter himself at the Versailles Treaty negotiations) espoused self-determination for the new Arab states. Archaeology had become a tool of British and French political imperialism. Then too, after World War I, Europe was broke. It was a mess and in shambles. European money did not exist for a long time to resume archaeological activities on the pre-war scale. Only the U.S. had the wealth to jump in and start some very dynamic research and to begin legitimately purchasing antiquities that had accumulated in shops in Egypt and Europe during the war. 1919-1920 Breasted went on a buying spree with money from millionaire donors such as Rockefeller (Standard Oil), Julius Rosenwald (Sears Roebuck), Martin Ryerson (Inland Steel) and others. American archaeological and humanitarian projects in the Middle East before the Great Depression tended to be well endowed. Unfortunately, its wealth and archaeological activity was not always well received by some European nations’ scholars and institutes who felt a keen sense of frustration, competition, and, yes, even envy. So, Rockefeller withdrew his $10 million offer and did what with it? At Breasted’s recommendation, he endowed the smaller, less grand Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem for $2 million. It is still there. It still functions as a tribute to both men, although nowhere near as grand as the Egyptian Museum would have been.

I have come across a paper back booklet which shows these same maps and list the antiquities and there placement in the museum, circa 1925. Is this something of importance?