In January 1959 the staff at the British Embassy in Havana were adjusting to their new hosts, the Cuban revolutionary government. Though headed by President Urrutia there was little doubt for the Embassy, as it was put in a despatch just over a week into the new era, that Fidel Castro would be ‘for some time to come the real power behind the throne’. In the same despatch appears the following speculation on the Cuban leader:

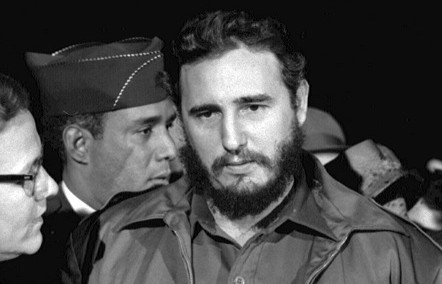

Fidel Castro at the Military Air Transport Service terminal in Washington DC, 1959 (Photo: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection, [LC-DIG-ppmsc-03256])

‘He is undoubtedly a man of enormous energy and great powers of leadership, but he is impulsive and has no experience of government. It remains therefore an open question whether he has the qualities necessary to weld into a coherent whole the discordant elements which have hitherto supported him and to give the country an administration both efficient and democratic.’ (FO 371/139398)

From this point onwards scrutiny of Castro intensified exponentially. For the past couple of years, while he led his guerrilla army in the eastern mountains, the Embassy had been reliant on scraps of information picked up through the grapevine and unreliable press reports for their assessments of him. Now they, like everyone else, had a direct window on the man with whom they were to do business in Cuba.

With events unfolding at a furious pace over the next couple of years and a Cuban government at times hostile to western diplomats, direct access to him in the form of interviews and meetings was hard to come by for the British. Nevertheless, impressions of this ‘exhibitionist’, as the British Ambassador would later identify him, were much easier to gain now that he occupied centre stage, seemingly relishing the limelight and making frequent and relentlessly long public speeches.

The focus of reports on Castro sent back to the Foreign Office from 1959, therefore, expanded to include constant references and detailed critiques of his personal character. His ideological beliefs remained somewhat unclear but analyses of his political character become increasingly laced with anxiety that he may be a communist in sheep’s clothing – a fear felt even more acutely by the Americans (conversations with whom are recorded in much Foreign Office correspondence on Cuba from this time).

From anti-communist to anti-American

In February 1959 Castro took up the post of Prime Minister (he did not become President of Cuba until 1976). His first visit to the US in his new role came shortly afterwards, in April, in which he sought to promote trade between the two countries – the whole visit conducted in his trademark olive green military fatigues. This initial courting of the Americans, which caused a flurry of reporting, included flat denials that he was a communist, as David Muirhead, British consul at the Embassy in Washington, recounted:

‘Castro’s remarks about communist influence in his regime and Cuba’s foreign policy were not always easy to understand, but he seems to have become increasingly outspoken on this; his strongest remarks on this were made during his visit to the United Nations on April 22 when he informed correspondents that “communism has no place in democratic ideals”.’ (FO 371/139421)

In the same report, Muirhead judges Castro to have done ‘a good public relations job’ on his US visit and goes on to say that the Embassy ‘would judge that there is now a disposition here to give Castro the benefit of the doubt.’

Whatever the truth in this evaluation, relations between the US and Cuba, strained by mutual suspicions and paranoid judgements on both sides, quickly soured following Castro’s return to his homeland. British diplomats report on an increasing anti-Americanism in Castro’s pronouncements over the coming months, which they generally consider crude and full of hyperbole – though the Foreign Office acknowledge of the Americans that ‘As we ourselves have found elsewhere, it is hard to be objective in one’s own back yard’ (FO 371/139421).

There are many references in correspondence sent from the Havana Embassy to Castro’s unpredictability and the intensely passionate, apparently uncontrollable, side to the man. One of the most damning judgments on this side of his personality appears in a report from P. R. Oliver, First Secretary at the Embassy, who describes a speech delivered by the Cuban Prime Minister in July 1959:

‘Even more significant than the vituperative phrases themselves was Castro’s manner of uttering them. I had not seen Castro on television for some weeks previously, and I was frankly appalled at his demeanor [sic]. The ranting demogogy [sic] and gesticulations were still there, more pronounced than ever; so was the hoarse impassioned voice. But it did seem to me that there were sinister overtones of a frenzy almost amounting to paranoia. The whole thing was unpleasantly reminiscent of Hitler.’ (FO 371/139421)

Despite this alarming portrayal, British representatives tended to paint Castro as a complicated, compelling and erratic character and steered away from describing him as a monster. At the end of that same July, Stanley Fordham, the Ambassador between 1956 and 1960, sent this description as part of the annual ‘Leading personalities in Cuba’ report:

‘A tall, powerfully-built man, Castro, particularly with his beard, is a striking figure. Although not strictly speaking a Communist, his ideas are extremely radical and he has introduced many far reaching measures of social and economic reform. Probably sincere in his concern for the underprivileged, but inexperienced, impetuous, intolerant of criticism and over-loquacious. Undoubtedly one of the most remarkable characters for many years to appear on the Latin American scene; but it as yet impossible to predict whether his influence thereon will be good or bad.’ (FO 371/139397)

The ‘influence of communists’

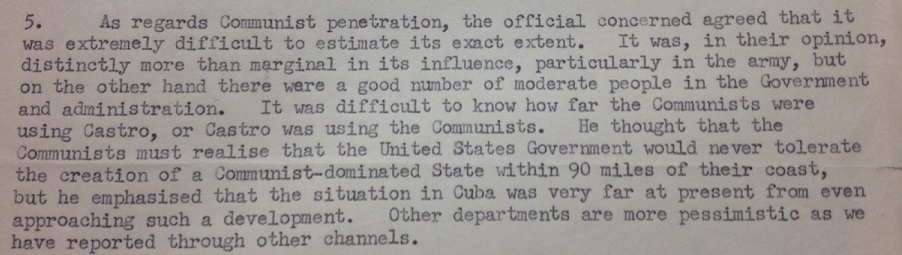

Extract from a report sent by the British Embassy in Washington in October 1959 (catalogue reference: FO 371/139421)

By the end of 1959 British diplomats were still referring to the ‘more extreme wing of the 26th of July Movement’ (FO 371/139403), to the ‘influence of communists’ or to ‘communist penetration’ within Castro’s administration but do not refer to Castro or his government as communist per se. Whether he was concealing his true beliefs is a possibility returned to again and again in British and American discussions and to this day remains a subject of debate. However, the Americans seemed to have made up their minds before the British. As Fordham put it in a despatch dated November 13, 1959:

‘Hitherto it has been almost axiomatic to regard Fidel as less extreme than some of his followers, upon whom he exercised a moderating influence; but, as the Head of the Political Section of the United States Embassy expresses it, it looks as if he had been “putting on an act.”

‘It is natural that United States officials should be intensely irritated by the libellous charges which Fidel personally has levelled against their Government and, so far as anti-Americanism is concerned, their assessment of him may well be correct. But to suggest, as they now seem willing to do, that he is as much a communist as “Ché” and Raúl is, I think, going too far. The present Cuban Government and its Prime Minister are certainly in many respects pretty repulsive, and extreme anti-Americanism usually goes with communism; but to argue “communists are anti-American, Fidel is anti-American, therefore he is a communist” seems to me false logic. I do not pretend to understand what goes on in Fidel’s extremely complicated mind, but I think that for the time being he should still be given the benefit of the doubt.’ (FO 371/139403)

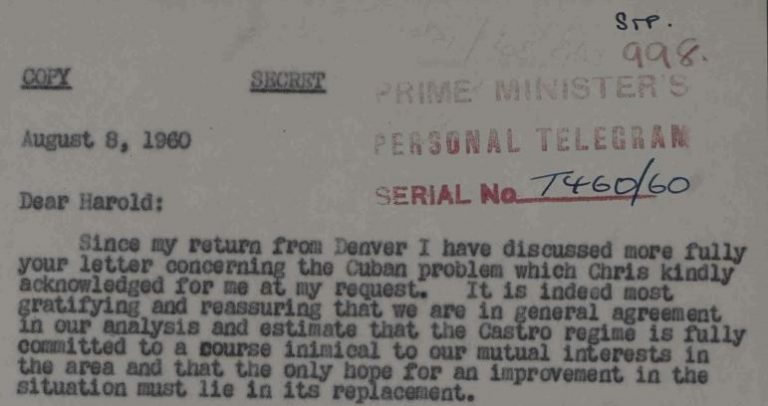

The benefit of the doubt ebbed and flowed over the course of the following year, by the middle of which the Americans were considering ways to forcibly remove Castro from power; British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and US President Dwight Eisenhower discussed the matter personally in July and August 1960 (CAB 301/158). Castro and his government had by this time already turned to the Soviets, who were now buying hundreds of thousands of tonnes of Cuban sugar and providing Cuba with much needed credit. Herbert Marchant, who had replaced Fordham as the British Ambassador in Havana, advised Macmillan to urge the Americans to adopt a more cautious approach, suggesting not only that ‘Castro retains a large measure of popular support’ within the country but also that he ‘might not be so wholly committed [to the Soviet bloc] as Guevara and Raul […]’ (CAB 301/158).

US President Dwight Eisenhower discusses the removal of Castro from power with Harold Macmillan in August 1960 (catalogue reference: CAB 301/158)

The British continued to offer this cautionary line to their American colleagues but could not persuade them from their determination to remove Castro by any means necessary. In June 1960, as Harold Caccia, British Ambassador in Washington, explained to the Foreign Office, the US State Department had already declared ‘Castro beyond redemption and that it is impossible to do business with him. They are, therefore, actively considering ways and means to bring him down’ (FO 371/148293).

‘I am a Marxist-Leninist’

By April 1961 the ways and means had been decided upon. A 1500-strong force of Cuban exiles, trained and financed by the CIA, invaded Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. It was all over in three days, the whole operation a shambolic failure – according to Marchant in his annual review, ‘an operation which, as seen from here, made the Suez campaign look like a successful picnic’. In the same review Marchant asserts:

‘What is certain is that he [Castro] has managed in 1961 to lead his country well and truly into the communist camp against the wishes and instincts of the majority of his people. This was a tour de force which, I believe, not even the prodigious Fidel Castro could have brought off had it not been for that blue-print for disaster the April invasion […]’ (FO 371/162308)

Seven months after the Bay of Pigs invasion, on December 2 1961 Castro declared in a five-hour speech ‘I am a Marxist-Leninist and shall be one until the end of my life’. Though the declaration confirmed what many had long suspected, the decision of the announcement underlines his previous reluctance to declare himself as such, and has fed into the debate about his true beliefs that has raged ever since. Even after the declaration the Washington Embassy told the Foreign Office ‘We think they [the State Department] do not all believe that Castro necessarily means it when he says he is a convinced Marxist/Leninist (FO 371/156153).’ Marchant, too, felt doubtful:

‘This is all a far cry from the liberal, democratic Cuba that 90 percent of Fidel Castro’s supporters had in mind when they rallied to his banner in the first days of 1959. Whether Fidel Castro himself had it in mind is something which not even his recent apparently naïve confession of faith make clear. I myself still incline to the theory submitted in my annual report last year, namely that Castro, the natural rebel, nationalist, dreamer of Napoleonic dreams, teamed up sometime in 1960 with the communists because he desperately needed their organisation, discipline and machinery to help him stay in power, get more power and ultimately to ride through Latin America on a white horse liberating the wildly cheering peoples.’ (FO 371/162308)

Whatever the truth of it, Castro’s declaration left no room for doubt about his intended direction for Cuba as ties with the Soviet Union became ever stronger. For the Soviets the relationship provided them with a strategically powerful foothold in the Western Hemisphere, just 90 miles from the US mainland.

In early 1962 they began negotiating with Castro over the installation of nuclear missiles in Cuba and by August of that year had begun building bases on Cuban soil from where the missiles could be launched. When US surveillance identified the bases, what has become known as the Cuban Missile Crisis but has always been known in Cuba as the October Crisis, ensued. It ended in humiliation for Castro, as described by Marchant in his annual review of 1962:

‘Then came the crisis and the removal by the Russians of their rockets and bombers – the world’s most public snub to the world’s most publicised primadonna. I myself saw Castro after the event. He was sallow, haggard and thin, mentally and physically deflated. Never has a prime minister had to undergo so agonizing a period of adjustment to unpalatable facts and never has one behaved in so unorthodox a fashion. He went of sulking like a small boy and took no further visible part for the next six weeks in the affairs of the state […]. It is not in his nature to think things out quietly on his own; he has to “talk them through”. He did so, emerged again like a happy oversized extrovert – all the six foot four inches of him – to take over with panache and full publicity the negotiations for the return of the invasion prisoners.’ (FO 371/168135)

A complex man

For the British, on the whole, there was often a sense of a battle, or at least an argument, going on within Castro’s government, and even within Castro’s mind, for its direction. He appears, in British eyes, to drift towards the communist camp rather than to march there – and certainly not to have secretly been there all along. This is in keeping with the British view, expressed on many occasions during these years, that Castro was, in general, a hard man to pin down. They saw him as egotistical and moody, restless and capricious and they never really felt they knew what he genuinely believed nor felt confident about what he would do next – partly, it seemed to them, because he was so impetuous and prone to violent fits of emotion that he could not possibly be sure either.

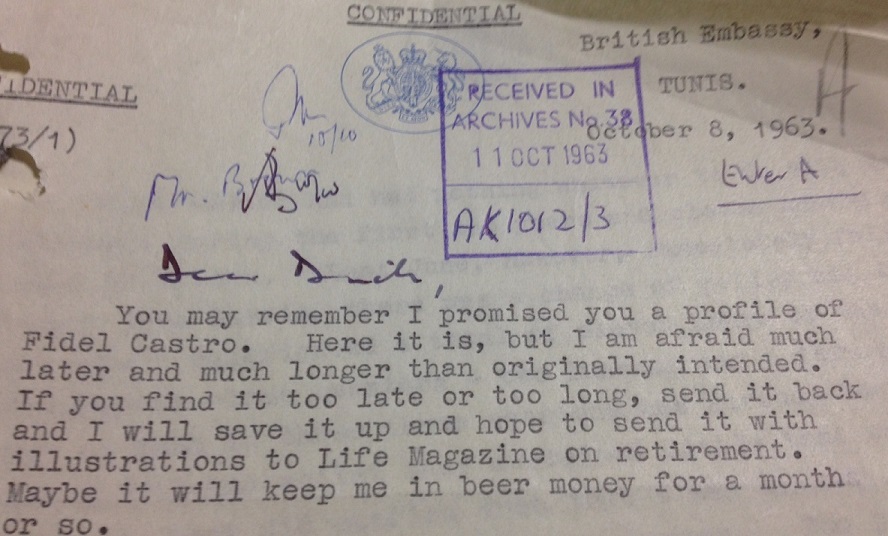

Some of the most poignant and searching assessments of Castro from this era came from Herbert Marchant who, by October 1963, had left Cuba to become the British Ambassador in Tunisia. His fascination with Cuba’s ‘Maximum Leader’, whom he met and spent time with on a number of occasions, compelled him to write his own lengthy Castro profile, which he shared with the Foreign Office that month, ten years after Castro had first become known to the British.

Cover note attached to Herbert Marchant’s 1963 profile of Castro (catalogue reference: FO 371/168136)

In it, he avoids a black or white depiction of what he sees as a hugely complex man, emphasising his conceit and ‘his almost completely egocentric self’ but recognising qualities such as his courage and a ‘genuine passion for the poor and under-privileged’. He recognises, too, the wildly varying perceptions of him that exist:

‘But what about the courage to carry out his convictions, what about his overall integrity of character? On this there is and can be no agreement between his enemies and followers. For the opposition he has broken solemn promises, sacrificed friends and principles for his personal ambition; by swinging the country into the Communist camp he has betrayed the revolution and he has done so with calculated ruthlessness. For the faithful, on the other hand, the true aims of the revolution have only been achieved through Castro’s courage in abandoning the naïve, ineffective liberal ideas of the early days in favour of Cuba’s brand of Marxism Leninism. There have been no broken promises, only a substitution of newly evolved ideas for outdated ones, better suited to meet a new situation.

‘Castro, of course, takes this line himself and has repeated it so often that he may well be beginning to believe it. Some such self deception, some such rationalisation of his country’s switch to Communism is vital to his ‘amour propre’ if he is to continue to see himself and himself alone as the supreme architect of Cuba’s destiny.

‘[…]I do not believe he is entirely happy about the road he is treading and I am sure that he is even less happy about the old friends he has lost in the process. We must not forget how much he likes people and particularly how much he likes people to like him. […]

‘How long before this absolute power will corrupt absolutely?… Will he mellow or will he become more arrogant, more Quixotic, more egocentric, more impossible to work or live with? I think this will depend in the measure of the success of his hopes and his projects for Castro and for Cuba.’ (FO 371/168136)

P.R. Oliver was a slow learner. He is on record dismissing the first hand information from my Uncle Jose Norman about the communist nature of the inner circle of Castro before Castro was defeated.

His attitude, caused the need of a desperate catch up process, which among other disasters cost the life of my father Leonard Daley, formerly of the Royal Engineers…..

Very illuminating. I wonder if the author Mr. Matt Norman is aware of several declassified CIA’s documents available online that quote the work done by British embassy political analysts and intelligence officers in regard to this topic. I also wonder if he is knowlegeable of how much the US came to rely on the British and Canadians for intelligence gathering and analysis after diplomatic relations were severed on January 3, 1961 and diplomatic personnel was removed from the island. Incidentally, all these documents are found in the National Archives of the United States and can be requested free of charge.