This blog post is part one of three in our Refugee Stories series for Refugee Week (15-21 June). Read part two from 17 June and part three from 19 June.

At the beginning of the First World War, the Assyrians[ref]The Assyrians were (still are) Christians established in what is now Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Iran.[/ref] of Urmia, in the west of Persia, at the border with Mesopotamia, fought with the Russians against the Ottomans. In 1916, fleeing before the Turks and the Kurds, 3,000 Assyrians fled from the mountains of Hakkari, in what is now southeast Turkey, and arrived in Urmia. When the Russian army withdrew after the 1917 Revolution, the Assyrians carried on, running a defensive campaign.

In July 1917, the Allies suggested the Assyrians should break through Ottoman lines and take over one of the Allies’ ammunition convoys, then return to Urmia accompanied by British officers. As soon as most fighting men had left Urmia, the Ottomans started advancing from the north, and those who had remained fled south, seeking protection behind the British lines. Thousands were killed by the Ottomans, or died of starvation before they could be rescued by the British (AIR 20/508).

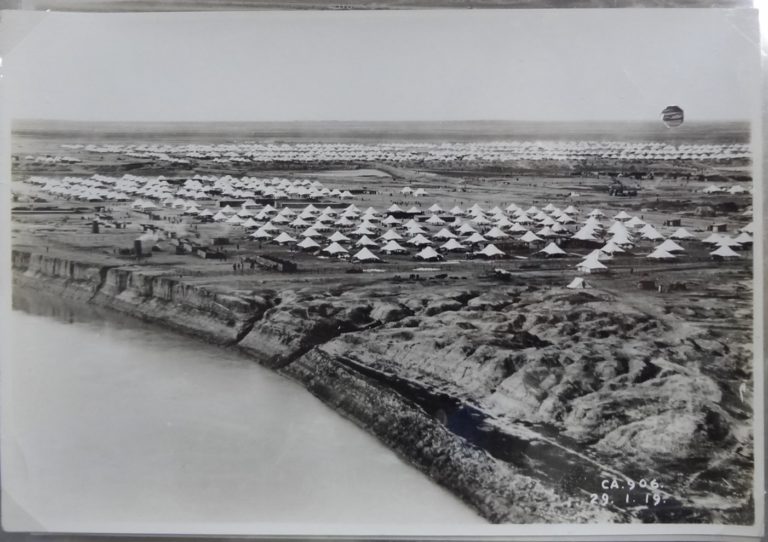

The British authorities in Mesopotamia set up a refugee camp at Baqubah, about 30 miles northeast of Baghdad. There were marsh mosquitoes and flies everywhere, animals were quartered above the site of a temporary water supply (when the medical officer objected he was told no other site was possible), and there were diseases (mostly dysentery and relapsing fever). As time went by, things started to improve. Medical treatment was rather efficient and the rations were roughly the same as those provided to Turkish prisoners of war, so the physical condition of the refugees improved, and death rates dropped dramatically (WO 95/5238/7).

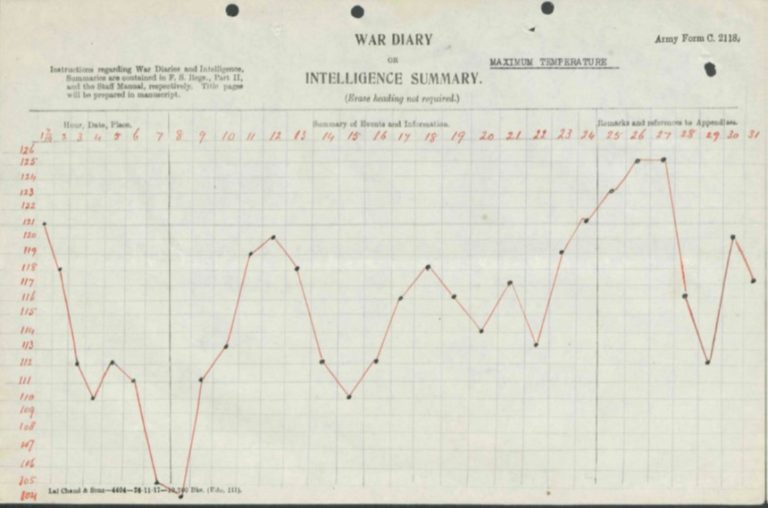

Still, conditions remained difficult. During the summer of 1919, it was incredibly hot. Temperatures reached 51 degrees celsius (125 degrees fahrenheit) inside the tents. The water pumps kept breaking down and people had to get water from the nearby canal, which led to very serious outbreaks of dysentery (WO 95/5238/8).

By the end of 1919, there were about 30,000 Assyrians in Baqubah, and one of the key issues for the British authorities was who was going to pay for them. On 23 July 1920, Hubert Young, at the Foreign Office, noted: ‘We do not want to enter into an acrimonious correspondence on this subject’ (FO 371/5126). But they did. The National Archives holds a series of memos written by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Curzon, the Secretary of State for War, Winston Churchill, the Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Austen Chamberlain. They spent an awful lot of time disagreeing on everything.

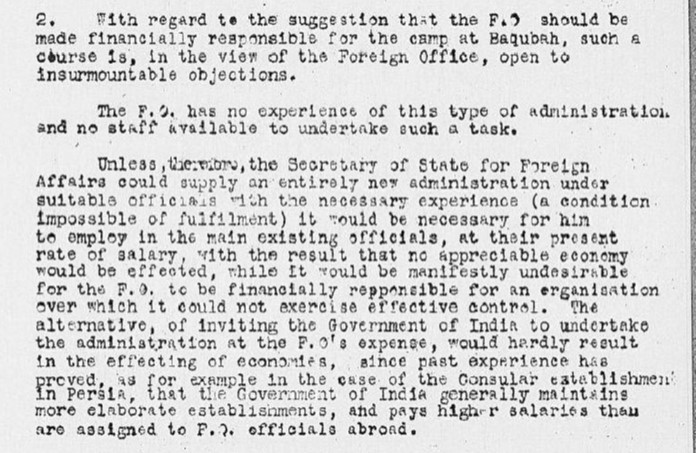

By November 1919, the cost per day amounted to £6,500. The costs were borne by the War Office, with funds coming out of the Army estimates. The War Office was adamant that responsibility should lie with the Civil Administration in Mesopotamia. The Civil Administration replied, rather smugly, that the refugees were a result of a military campaign for which the military authorities had been responsible. In November 1919, the Chancellor of the Exchequer suggested the Foreign Office should be made responsible, and should sort things out either by organising repatriation or by securing local settlements. The Foreign Office commented a few days later:

‘with regard to the suggestion that the F.O. should be made financially responsible for the camp at Baqubah, such a course is, in the views of the Foreign Office, open to insurmountable objections. The F.O. has no experience of this type of administration and no staff available to undertake such a task’ (CAB 24/93/96).

The costs, they concluded, should be borne by the War Office. The War Office protested that it had no control over either the policy which dictated this expenditure or the steps necessary to eliminate it – that’s to say the repatriation of the refugees.

It was the same when it finally came to the repatriation of the refugees. The War Office thought it was a diplomatic rather than a military matter, and didn’t see why it should pay for it. Churchill was particularly annoyed that it was artificially inflating military expenditures and therefore gave the wrong impression as to the actual cost of the Army in Mesopotamia.

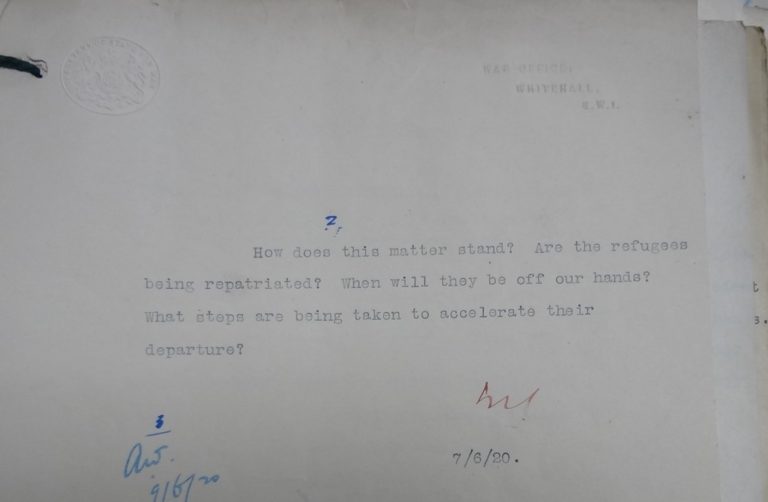

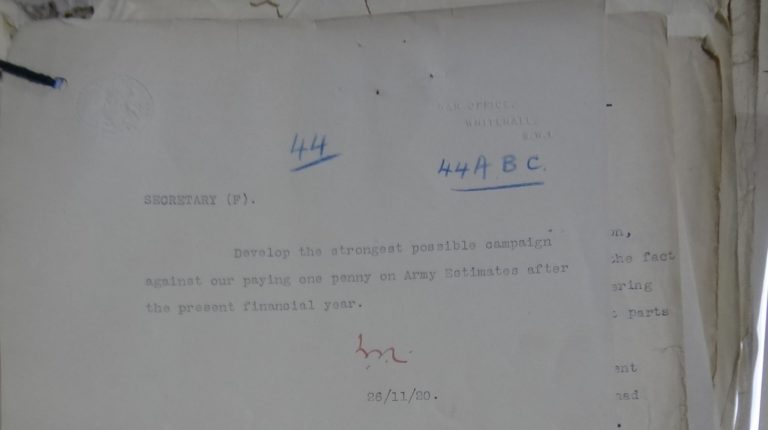

As time went by his notes and tone became less and less diplomatic. On 7 June 1920, he wrote: ‘How does this matter stand? Are the refugees being repatriated? When will they be off our hands? What steps are taken to accelerate their departure?’ On 26 November, he wrote a particularly curt note: ‘Develop the strongest possible campaign against our paying one penny on Army estimates after the present financial year’ (WO 32/5231).

On 12 January 1921, the War Office informed the Civil Commissioner in Baghdad that the Army would stop paying as of 31 March and that they would have to find another solution. The Secretary of State for India took a different approach and wrote on 16 November 1920:

‘It may not be out of place to remind the Cabinet that the harbouring and disposal of these refugees were nothing less than a debt of honour which it was impossible for His Majesty’s Government to repudiate’ (CAB 24/115/1).

The question of the repatriation of the Assyrian refugees was of paramount importance, and it was extremely complicated. There were two very distinct groups of Assyrians: some of them came from the mountains north of Mosul (the Mountaineers, or Hill Assyrians), and some of them from the plain region of Urmia, in Persia.

It was initially suggested to repatriate the Urmians to Urmia via Hamadan, and the Mountaineers to the mountains via Mosul. The Assyrian patriarch immediately protested that it would destroy national unity, so it was decided to repatriate them all together.

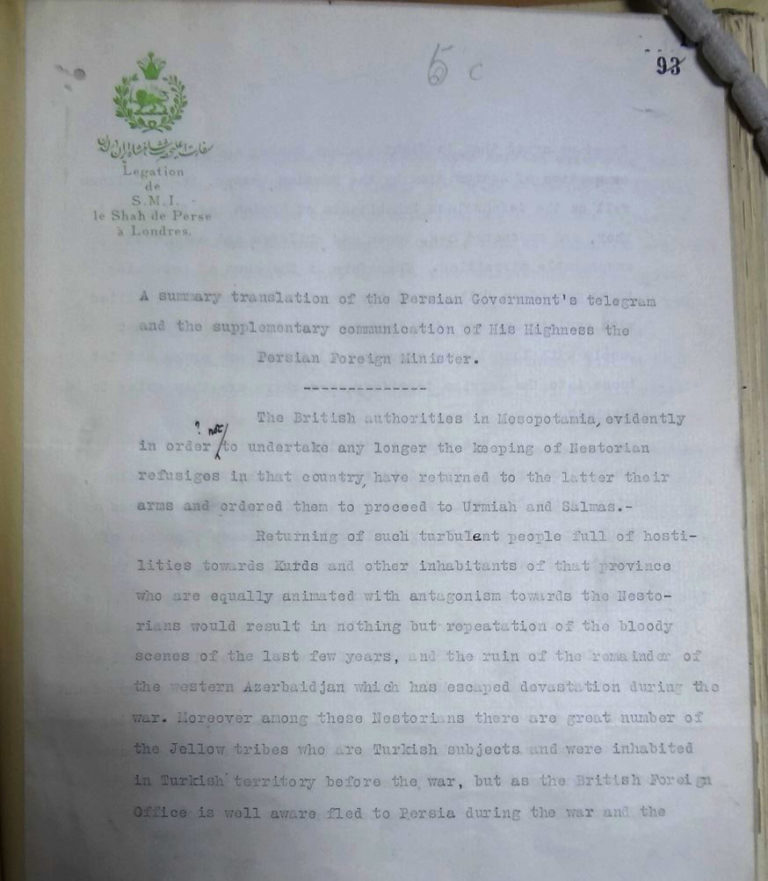

In April 1920, Arnold Wilson, the British Civil Commissioner in Baghdad, telegraphed proposals for the repatriation of the Assyrians to a region lying partly in Mesopotamia and partly in Persia, where they thought they could maintain themselves without further assistance from Britain. The Assyrians, he said, were only asking for weapons to defend themselves and to ‘constitute themselves once more into an independent community’ (CAB 24/108/72). Mid-May 1920, the Persian Ambassador transmitted a very strongly worded note from his government. They wrote:

‘Returning of such turbulent people full of hostilities towards the Kurds and other inhabitants of that province who are equally animated by antagonism towards the Nestorians would result in nothing but repetition of the bloody scenes of the last few years’ (FO 371/5125).

They also pointed out that many of these Assyrians were actually Turkish subjects who had only fled to Persia during the war. They therefore refused to take any responsibility. It was swiftly decided to confine repatriation to non-Persian territory.

By November 1920, the Assyrians were concentrated in the Mosul Vilayet and repatriation was made even more difficult by the Arab uprising. They were on the move, but had to fight their way through. By then it had become obvious that the repatriation scheme had failed.

The Assyrian leaders, Lady Surma from Europe and General Agha Petros from Mesopotamia, were asking that the Assyrians should be granted autonomy. They wanted to be part of Iraq, but under direct British control, and eventually took their demands to the Lausanne Conference in 1923 (CO 1073/169).

The Autonomous Assyrian State never materialised. The Assyrians were dispersed in several small groups in Iraq. They continued their pursuit of statehood despite the establishment of the Iraqi state in 1932, petitioning the League of Nations for autonomy, protection, and a guarantee of freedom to emigrate out of Iraq in the event of violence against them.

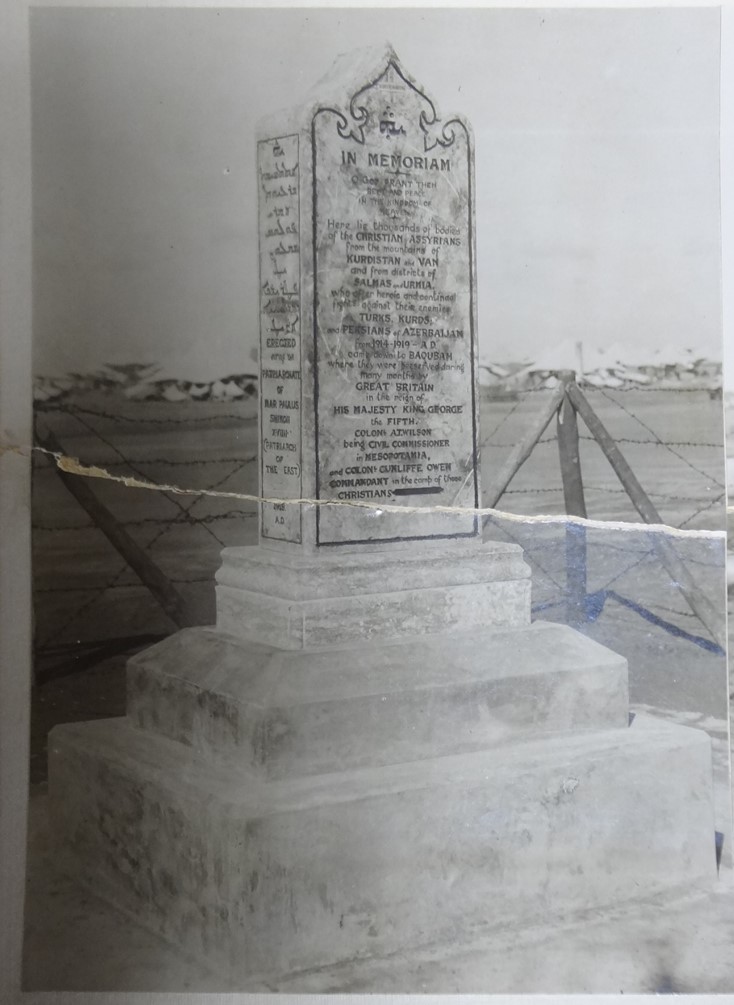

A memorial stone was erected at Baqubah in 1919. The stone no longer stands. Like the Assyrians, it came under heavy fire, and what remained was dispersed.

On the Record: Refugee Stories available now

To mark Refugee Week we have made a bonus episode of our podcast On the Record at The National Archives, which is now available on the Archives Media Player and on podcast listening apps.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts

You can also catch up on previous series in which have uncovered the true stories of famous spies and looked at protest – from the medieval Peasants’ Revolt to Black power in the courtroom. Most recently we have read famous love letters, and between the lines of less obviously romantic records, to discover the love stories of everyday people from the last 500 years.

Thank you Juliett! I am a researcher for the Mar Shimun Memorial Foundation and this is the first time I’ve seen a photo of the Baqubah monument! Interesting blog post. I would love to hear more — I have limited access to the National Archives online and hope to be able to come to London in the near future for further research. If you have other posts about the Assyrians from the archives, I’d love to know about them. Thank you.

Hello, in reading H.H. Austin’s book “The Baqubah Refugee Camp” it is mentioned a census of the refugees was taken. I would be very interested in what sources would be available to track down and obtain a copy of that census list. I had relatives that were among those refugees. Would you have any suggestions? Thanks in advance.

I am interested in direct recruitment form Refugee Camps, ie, employers in Australia who would offer jobs that could be applied for before coming to Australia.

Can you help with information.

Thanks to Brits who betrayed the Assyrians for not fitting in their plans.

I am currently working on researching the Assyrian issue in Iraq and the British and League of Nations role in this issue between 1918 and 1935. So I need documents related to this issue and cooperation with other minorities in the race to achieve some kind of self-rule.

Dear Saied,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to research, please use our live chat or online form.

We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

Good Morning! Very interesting to read. I am trying to find a list of refugees in the camp. I have their section – 27 . Thank you for your help.