Last Friday saw people around the country marking the anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre, which took place on 16 August 1819, when some 60,000 men, women and children gathered at St. Peter’s Field to listen to the radical orator Henry Hunt’s call for the reform of Parliament, but were attacked by troops, resulting in as many as 18 deaths.

As part of a wide programme of activity to mark this important milestone in the history of the struggle for rights and representation, Royal Holloway, University of London, and The National Archives launched the Archives Alive: Peterloo project. Archives Alive brings to life contemporary records detailing the prelude to and aftermath of the massacre, as well as a range of accounts of the day itself. We were pleased to announce earlier this year that the project received a grant of £10,000 from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and the videos were released on the university’s Citizens project YouTube channel on Friday 16 August 2019.

The majority of videos, all presented by professional actors, are based on archival material held at The National Archives. Spread across numerous document series, we can see various accounts of government officials, magistrates, and reformers, as well as contemporary newspaper report clippings and radical pamphlets.

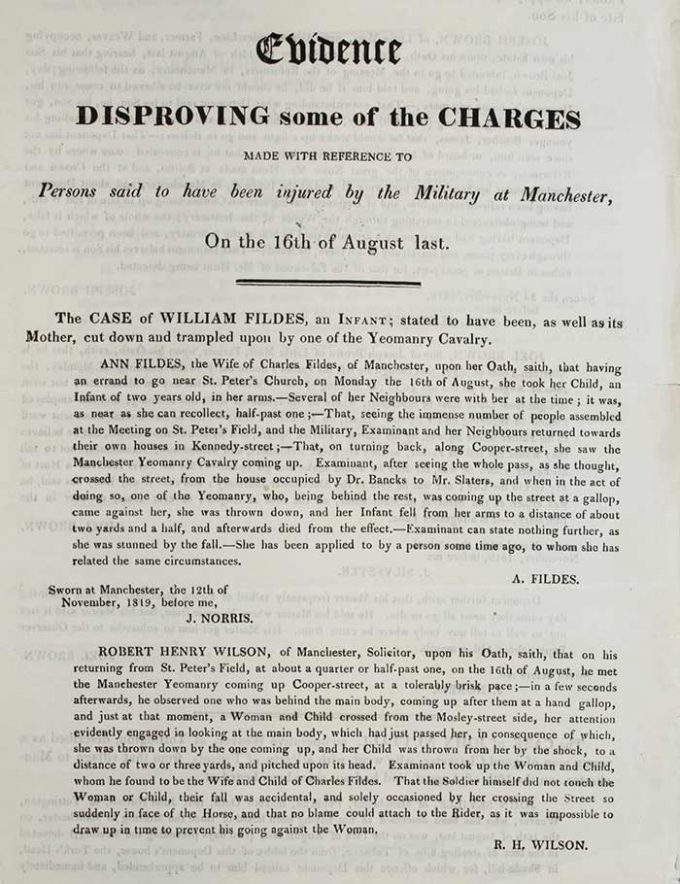

‘Evidence disproving some of the charges’, pamphlet published in the wake of Peterloo, November 1819. Catalogue reference: HO 42/199, folio 217

The Archives Alive project sought to take what we saw as the records’ greatest asset – their rich language and articulation of key arguments being used at the time – and re-interpret these for a 21st century audience through dramatization. In conjunction with this, we also wanted to highlight the breadth of the Peterloo records, drawing attention to the many differing opinions and interpretations held within personal testimonies and government correspondence.

The main challenge was sifting through the abundance of material held primarily within The National Archives records HO 42/ 190, HO 42/192, and TS11/1056 to locate the records that presented either the most significant or interesting and perhaps overlooked interpretations of events. Fortunately, the project team was not alone in this endeavour and was assisted by volunteers from both the U3A and The National Archives. Over the course of two afternoon Research Retreats at Royal Holloway, our team of volunteers helped to identify and transcribe what they regarded as some of the most interesting accounts, well-suited to dramatization.

These afternoon sessions proved to be very productive, and the social nature of group transcription allowed everyone to exchange interesting vignettes and accounts as we went. From a project perspective, it was rewarding to see such a deep level of engagement with the records and note that they did have the power to alter people’s original beliefs and perceptions of the massacre.

Having identified potential records to dramatise, three distinct groups began to emerge. Material that focused on the prelude to Peterloo, the massacre, and the aftermath. Upon reflection, we were fortunate that these groupings appeared naturally, but their emergence was of clear benefit to the project.

These groups provided the project with a vehicle to situate the massacre into the wider context of 19th century reform, hoping to provide a more nuanced understanding of why the meeting ended as it did. Within these groups, the team were keen to pick a balanced selection of accounts, reflecting the views of the government and reformers alike.

Having agreed upon our final selection of accounts and testimony, we cast actors and arranged filming. We deliberately opted for the visual style of our films to be simple and modern. For instance, our actors are deliberately not dressed in period costume nor cast-based on their resemblance to the character they represent. We believed this was not required and would distract from the power and persuasiveness of the arguments captured in the written record.

The finished videos present a fascinating window through which to view the prelude to Peterloo, the massacre, and its aftermath. Each video offers a different interpretation and way of engaging with this period of British history. From the group of videos dealing with the prelude to Peterloo, Henry Hunt’s public invitation to the meeting at St Peter’s Field, where he asks reformers to come with ‘no other weapon but a self-approving conscience’, is an obvious highlight.

Equally, the support shown from the Manchester Female Reform Society serves as a powerful reminder that women were not passive observers in these political debates. Accounts of the massacre vary enormously; Major Dyneley’s enthusiastic description of the day’s events encapsulate the sordid enjoyment that some took from the opportunity to ‘deal a blow’ to the reformers.

Finally, in our selection of videos concerned with the aftermath, the two competing accounts concerning the Trumpeter, Edward Meagher, demonstrate how both sides sought to frame the massacre and its aftermath to suit their narrative of events.

Over the course of this short project, Archives Alive: Peterloo has demonstrated the enduring power of the archival record. Re-imagined for a 21st century audience, these films offer new opportunities for learners of all ages and abilities to engage with and interpret them. We are also pleased to report that two of the Archives Alive videos, based on material held by the Parliamentary Archives, currently form part of UK Parliament’s ‘Parliament and Peterloo’ exhibition in Westminster Hall (open until 26 September 2019) and that all 18 videos will soon be permanently accessible via The National Archives website.

Hand coloured engraving of Peterloo Massacre exhibited by travelling showman. Sent to the Home Office by Reverend G Burrington of Chudleigh, Devon, November 1819. Catalogue reference: MPI 1/134, extracted from HO 42/199

Above all else, the project highlights the centrality of the record; from these surviving fragments of our past both historians and members of the public can form their own interpretations and engage in historical debate. We hope, in some small way, that Archives Alive: Peterloo will enable everyone to engage in this process and develop a more nuanced understanding of the Peterloo Massacre in this bicentenary year.