Young Bachelor (London, N.W.), 25, cultured, artistic tastes, would be glad of congenial chum about same age, especially music-lover. Photo appreciated. Genuine. (886.)

Blind dates, speed dating and, increasingly, online apps – in the 21st century there are countless ways for people to meet other people, whether for love, lust or companionship.

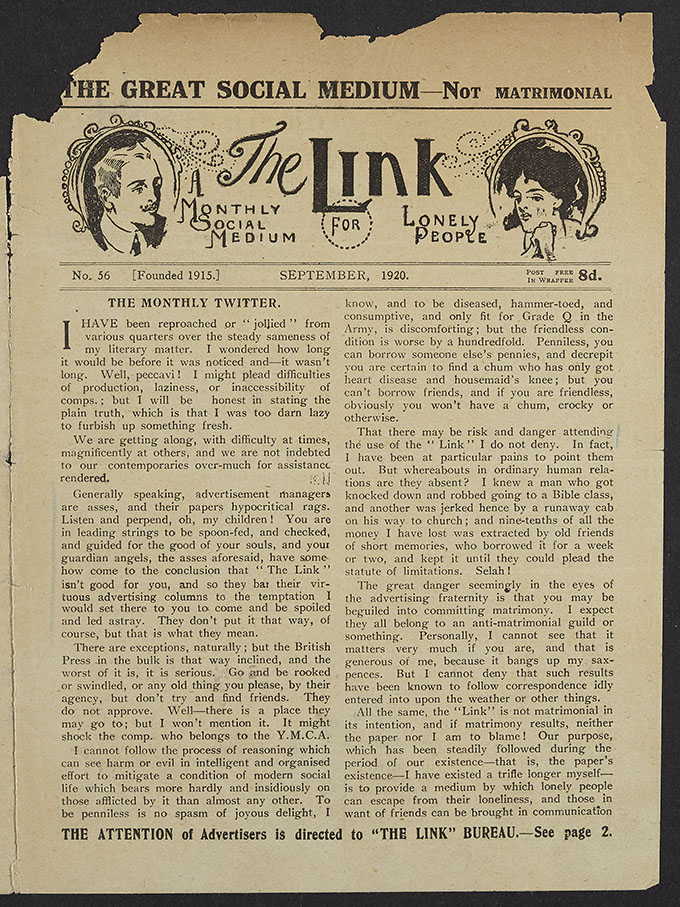

The Link: A Monthly Social Medium for Lonely People

As part of the Being Human Festival, we have set out to ask an important question: in an era when the law criminalised your love, how was it possible to meet members of the same sex?

To answer this, I want to introduce you to The Link, a ‘lonely hearts’-style publication from the early 20th century, that sought to connect people. It was founded by Alfred Barrett in 1915, in response to a perceived crisis of loneliness prevalent within society at the time.

The Link, A Monthly Social Medium for Lonely People, No. 56. September 1920. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/283

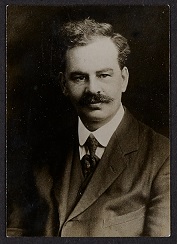

Barrett was a prolific journalist and editor, who had published a great number of books in his earlier life under the pseudonym ‘R Andom’. But in 1915 Barrett was one of the first to publish a magazine entirely devoted to lonely hearts advertising. These adverts didn’t just fill a few pages at the back of the magazine – they provided its entire content.

Photograph of Alfred Walter Barrett, the proprietor of The Link. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/283

The Link described itself as ‘not matrimonial’, differentiating it from competitors and companion volumes of the era. Barrett claimed the publication could be used by people seeking companionship. Others, however, believed it would facilitate more casual sexual encounters. While the personal advert was not a new concept, this tone was. By explicitly defining itself as looking beyond marital love, it pushed the boundaries and social norms of the era.

The adverts were divided into three major sections of personals: Ladies, Civilians, and Soldiers and Sailors. There were adverts by war widows, disabled soldiers and people searching for less formal relationships, reflecting the changing society and social values of the 1920s.

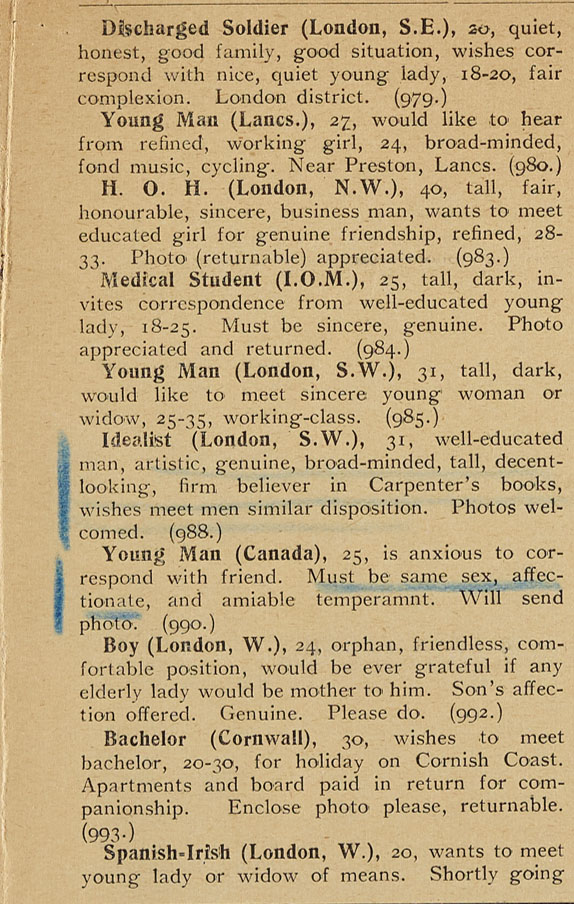

The classified adverts

While these classified ads look in many ways like past equivalents of modern dating profiles, this era could not have been any more different from today’s Grindr generation.

People had up to 25 words to describe themselves and what they were seeking.

Young Gent (Bristol), 26, good-looking, would like correspondence with own sex, 18-26. Must be well-educated, of good appearance. Photos appreciated. All letters answered. (940.)

However, the publication wasn’t used entirely as Barrett had planned. Through these pages, men used the coded and suggestive language of classified adverts to meet other men. This was extremely risky, as in 1920s Britain homosexual acts between men were criminalised. It was never illegal to be gay, but many of the associated practices were criminalised.

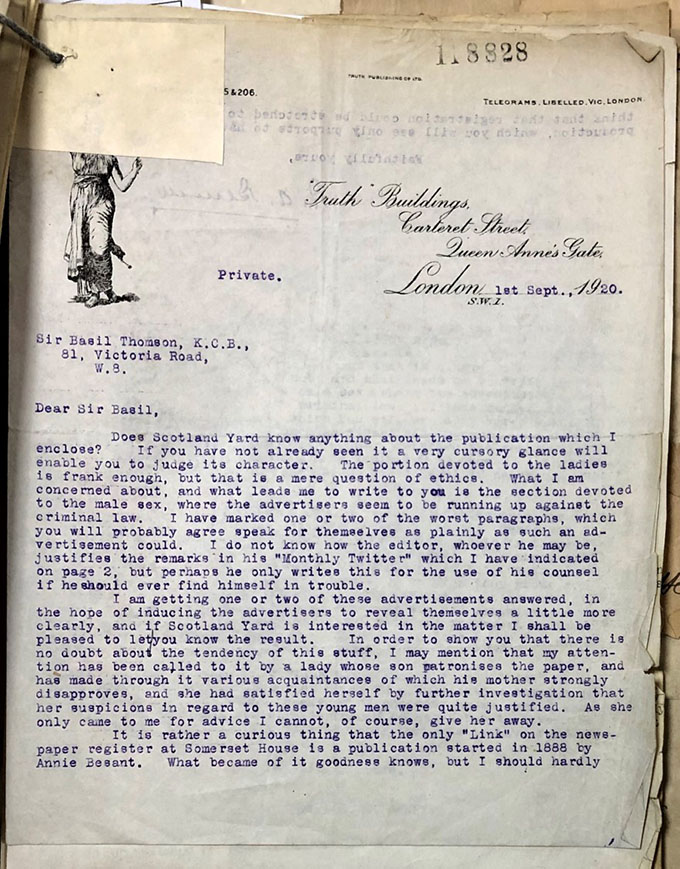

A letter from R A Bennett, editor of the moralistic newspaper Truth, had highlighted the publication to the Metropolitan Police. A copy of The Link was sent to them, with pencil markings carefully underlining certain sections and key words. The Link was ultimately investigated for conspiracy to corrupt public morals.

Letter of complaint by R A Bennett, as sent into Scotland Yard. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/283

‘The portion devoted to the ladies is frank enough, but that is a mere question of ethics. What I am concerned about, and what leads me to write to you, is the section devoted to the male sex, where the advertisers seem to be running up against the criminal law.’ And, the letter argues, these sections, ‘speak for themselves as plainly as such an advertisement could.’

Men meeting other men can be inferred from some of the coded language of this publication: ‘artistic’, ‘bohemian’ and ‘unconventional’. Concerns were also highlighted about advertisements that seemed to suggest an element of payment or just ‘loose’ morals.

The State’s attempts to suppress and regulate sexuality has left us with many potential sources for the experiences of LGBTQ+ people – The Link being one such example. Despite the fact these records are found in police files, they can give us a fascinating insight today into what it might have been like to have been gay in the past.

Sample list of classified adverts from issue No. 56 of The Link, September 1920, as underlined by R A Bennett. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/283

‘Jolly’ and ‘sporty’

In the decades after this, other hidden modes of communication would develop in the LGBTQ+ community across the 20th century – most famously Polari. However, this early coded language is less subtle. It is littered with clichéd ideas of effeminacy, which at the time was often associated with homosexuality, or stereotypes around an uber-masculine male identity.

The classified adverts display a fraught tension between the author sending a clear message about their sexuality while attempting to hide from the law. The police, however, had learnt that words such as, ‘artistic’, ‘musical’, and ‘unconventional’, all acted as indications of homosexual interest. Another approach was to list artists and literary figures who represented a kind of ‘queer cannon’, notably Oscar Wilde, socialist Edward Carpenter, who openly published about sexuality, and the American poet Walt Whitman.

The vast majority of the same-sex classified adverts are from men seeking other men. However, there are some written by women. In this era, male homosexual relationships were criminalised in a way that lesbian relationships were not. There has long been discussion about the impact this had on lesbian identity at the time. It wasn’t illegal, and to some extent this meant it was less visible. Certainly, within the pages of The Link, women directly appealing to other women was much rarer. Similar coded language occurs in these adverts: ‘unconventional’, ‘lonely’, ‘jolly’, ‘bachelor girl’ and a noted interest in ‘studying human nature’…

Unconventional (Wales), 30, well-educated, literary tastes, fond of travel, dancing, good times, and studying human nature, would like correspondence.

But ultimately the police were far less interested in these adverts between women because they weren’t contravening the law. In turn this leads to less focus on women’s relationships in the records.

Despite the criminalisation of their love, queer people continued to strive to find ways to meet and defy the law. The Link provided them with one means of doing that.

In the next blog post I am going to look at the consequences of men meeting other men through The Link, and explore the inherent risks and consequences of being caught.

Event: Classified – A performance of queer dating ads inspired by archives

Image of the performer Timberlina by Ren Brocklehurst

This research is being used in a Being Human Festival event held by The National Archives and Bishopsgate Institute. The event seeks to celebrate and reclaim the voices in these classified ads and make them out, loud and proud 100 years on in a current prominent queer venue, the Royal Vauxhall Tavern.

The performer Timberlina and DJ Auntie Maureen will bring to life some of these coded, intriguing and sometimes naughty personal ads found in our collections. Event details can be found here.

Being Human

Being Human is the UK’s only national festival of the humanities. A celebration of humanities research through public engagement, it is led by the School of Advanced Study at the University of London, in partnership with the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the British Academy.