Missing the World Cup already? It ended well for France, who got a second star 20 years after the first one, and were able to claim that the Trophy was finally coming home. In 1969, however, the qualifying games for Mexico-70 went dramatically wrong for Honduras and El Salvador, who fought a very brief but very real war from 14 to 18 July.

The conflict obviously had deeper causes than football, but the games were the last straw. In 1969, El Salvador – the smallest country in Central America – had an incredibly high birth rate. Hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans had crossed the border to settle in Honduras, sometimes illegally, to find land to cultivate. In April and May, the Lopez Arellano government in Honduras, facing multiple strikes, started enforcing the 1962 agrarian reform. It stated: ‘No-one may be dispossessed of their lands if they have owned them five years before the promulgation of the law’, but excluded all those who were not Honduran by birth (FCO 7/1211).

Anti-Salvadoran feelings became prevalent in Honduras, where slogans such as ‘Hondureño, toma un leño y mata a un Salvadoreño’ (Honduran, pick up a stick and kill a Salvadoran) started to appear and ‘a small exodus’ of Salvadorans began in May (FCO 7/1588).

Honduras and El Salvador played the first qualifying game on 8 June 1969 in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras. No major incident occurred. Lawrence L’Estrange, the British ambassador to Honduras, later reported: ‘The reason why there was no trouble is simple enough: Honduras won, though by the skin of their teeth by a goal scored in the last minute of the match’ (FCO 7/1210).

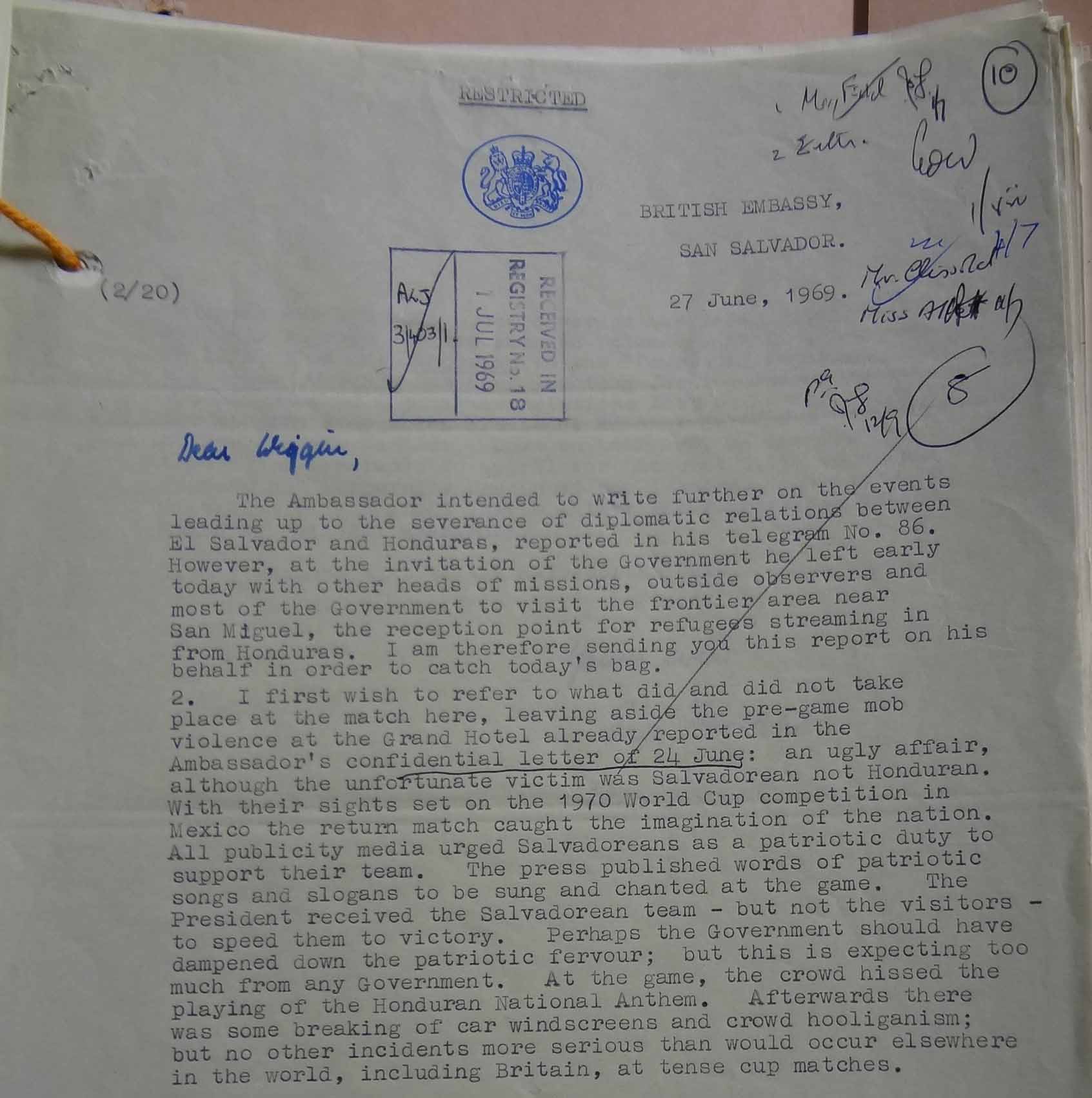

The second game, held in San Salvador on 15 June, was a different story. The Honduran players were kept awake all night by the beating of tin cans and projectiles hurled at their windows. During the game, ‘the crowd hissed the playing of the Honduran National Anthem’. It was after the game, though, that things turned into what Farrar, the First Secretary at the Embassy in San Salvador, later described as ‘an ugly affair’.

In San Salvador, a young man was killed and a post office was ‘substantially damaged’ (FCO 7/1210). Robert Gregg, a credit rating specialist and local representative of the Confederation of British Industry added: ‘Unfortunately, some visitor from Honduras standing in the doorway of his lodgings, yelled out “viva Honduras” as a car went by. Someone in the car shot a pistol off and nicked him in a meaty place’ (FCO 7/1211).

Farrar put it down to ‘crowd hooliganism’, and claimed there were ‘no other incidents more serious than would occur elsewhere, including Britain, at tense cup matches’ (FCO 7/1210).

In Tegucigalpa, the Salvadoran victory (3 – 0) sparked off riots. Shops owned by Salvadorans were sacked and cars bearing Salvadoran number plates were burnt. Trying to find a silver lining, L’Estrange wrote to the FCO, highlighting that at least ‘no player at either match was felled by missiles from the crowd as an Italian footballer recently was at Manchester’ (FCO 7/1210). The ‘small exodus’ of Salvadorans from Honduras, however, became a massive one.

Almost immediately after the game, politicians and journalist in both Honduras and El Salvador started a propaganda war of unbelievably vitriolic intensity.

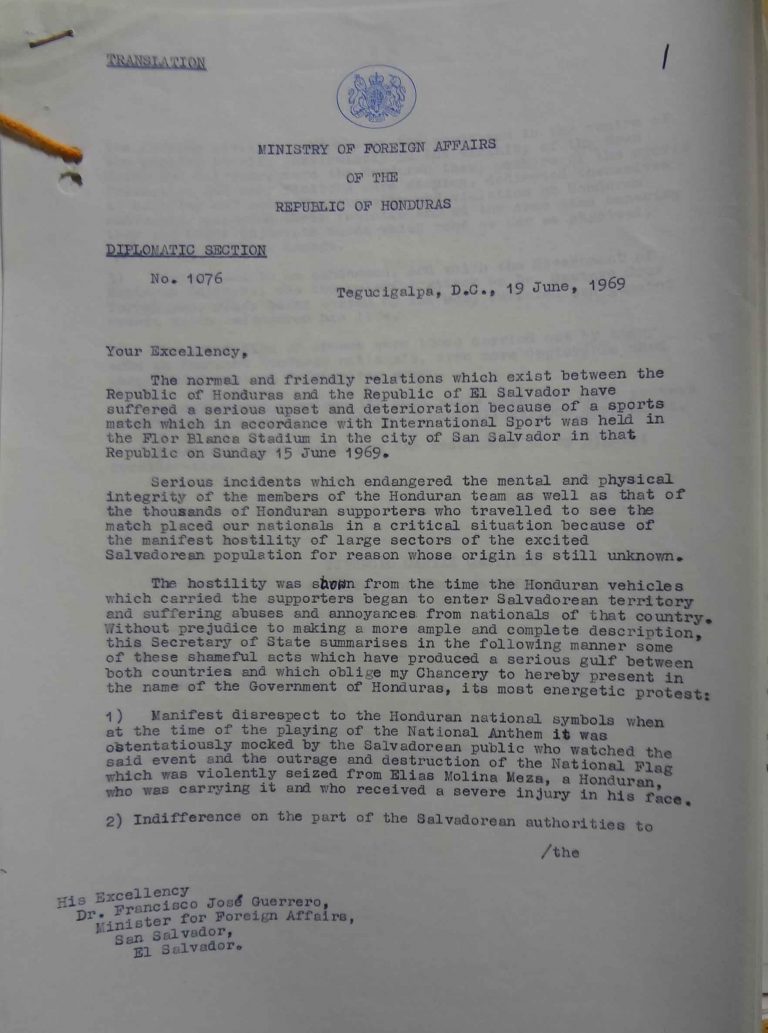

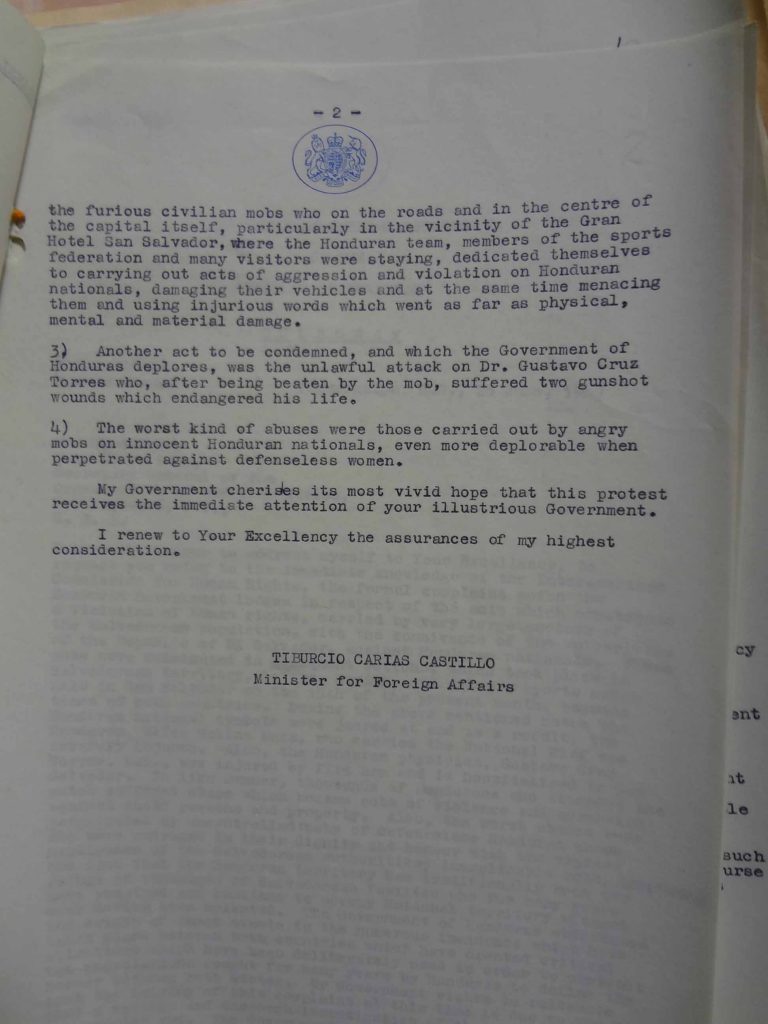

On 19 June 1969, the Honduran Minister for Foreign Affairs wrote to his Salvadoran counterpart, protesting vigorously at the treatment of Hondurans in San Salvador after the game and at the

indifference on the part of the Salvadorean authorities to the furious civilian mobs who on the roads and in the centre of the capital itself (…) dedicated themselves to carrying out acts of aggression and violation on Honduran nationals.

The national symbols of Honduras, he wrote, had been disrespected, the flag snatched violently from the hands of the player carrying it, causing him serious injuries (FCO 7/1210).

Tiburcio Carias Castillo to Francisco José Guerrero, 19 June 1969 (catalogue reference: FCO 7/1210)

Almost simultaneously, the Salvadoran Minister for Foreign Affairs addressed a note verbale to his Honduran counterpart, protesting at the treatment of Salvadorans in Honduras:

Sporadic and occasional incidents resulting from human and spontaneous expressions of euphoria at the sporting contests like those which took place (…) cannot at any time be described as acts regrettably directed against the person nor, much less, justify the massive and disproportionate violence visited on the Salvadoreans living in Honduras, innocent victims of these sporting encounters in which they have taken no part whatsoever (FCO 7/1210).

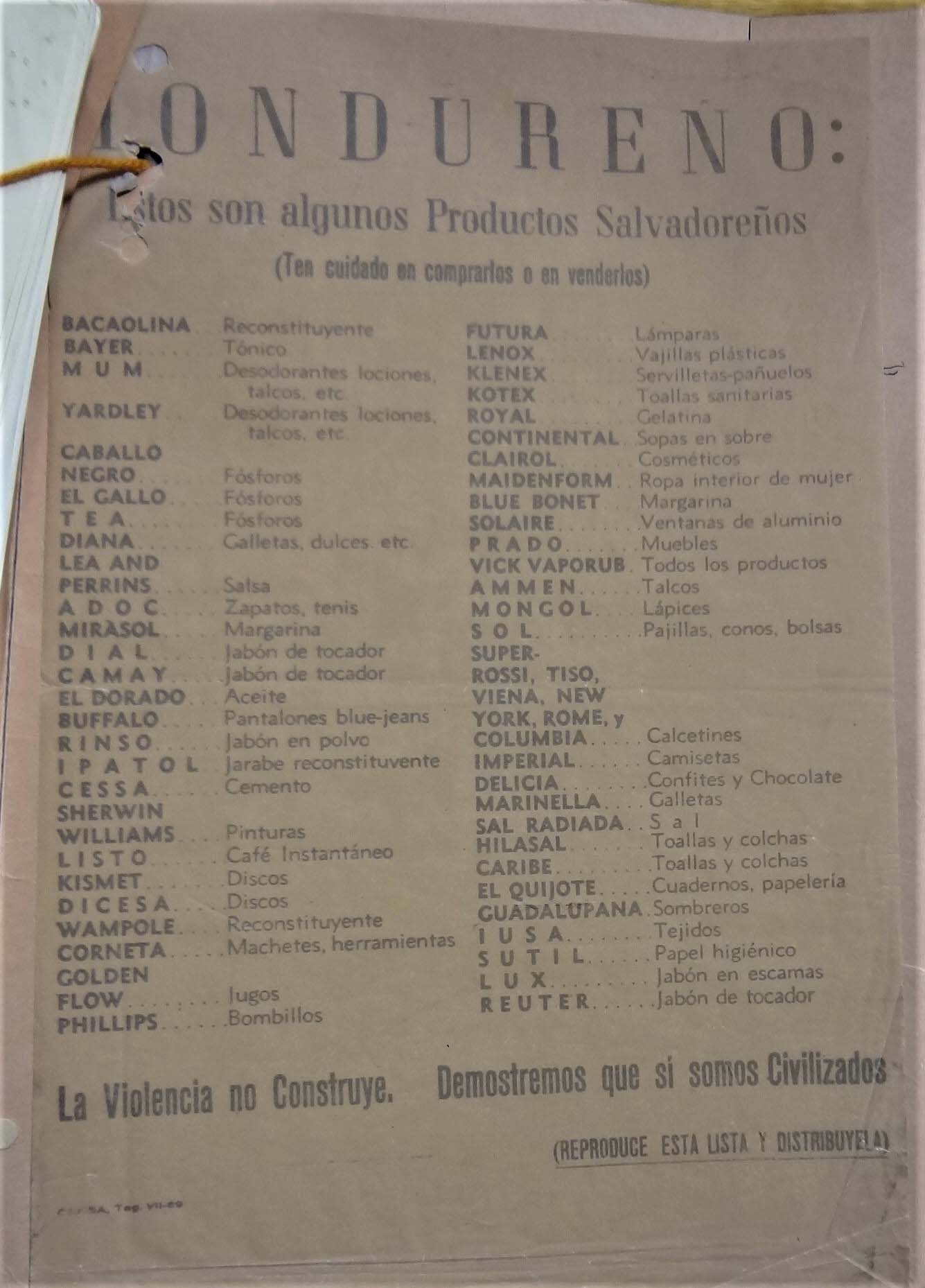

By the end of June, the American embassy estimated that about 10,000 Salvadorans had fled Honduras. All Salvadoran products were boycotted, and stickers and handbills appeared on cars and in shop windows (FCO 7/1212).

Handbill circulated in Honduras, urging people to boycott Salvadoran products, 1969 (catalogue reference: FCO 7/1212)

The third game was held on 26 June 1969 in Mexico City (both Guatemala and Costa Rica refused to host). The Salvadoran team won 3 – 2, qualifying for the World Cup. On the same day, El Salvador broke off diplomatic relations with Honduras.

![Note verbale addressed to the Honduran Minister of Foreign Relations [translation], 26 June 1969 (catalogue reference: FCO 7/1210)](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/01142214/to-use-fco-7-1210-3879-768x1004.jpg)

Note verbale addressed to the Honduran Minister of Foreign Relations [translation], 26 June 1969 (catalogue reference: FCO 7/1210)

![Note verbale addressed to the Honduran Minister of Foreign Relations [translation], 26 June 1969 (catalogue reference: FCO 7/1210)](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/01142225/to-use-fco-7-1210-3880-1-768x501.jpg)

Note verbale addressed to the Honduran Minister of Foreign Relations [translation], 26 June 1969 (catalogue reference: FCO 7/1210)

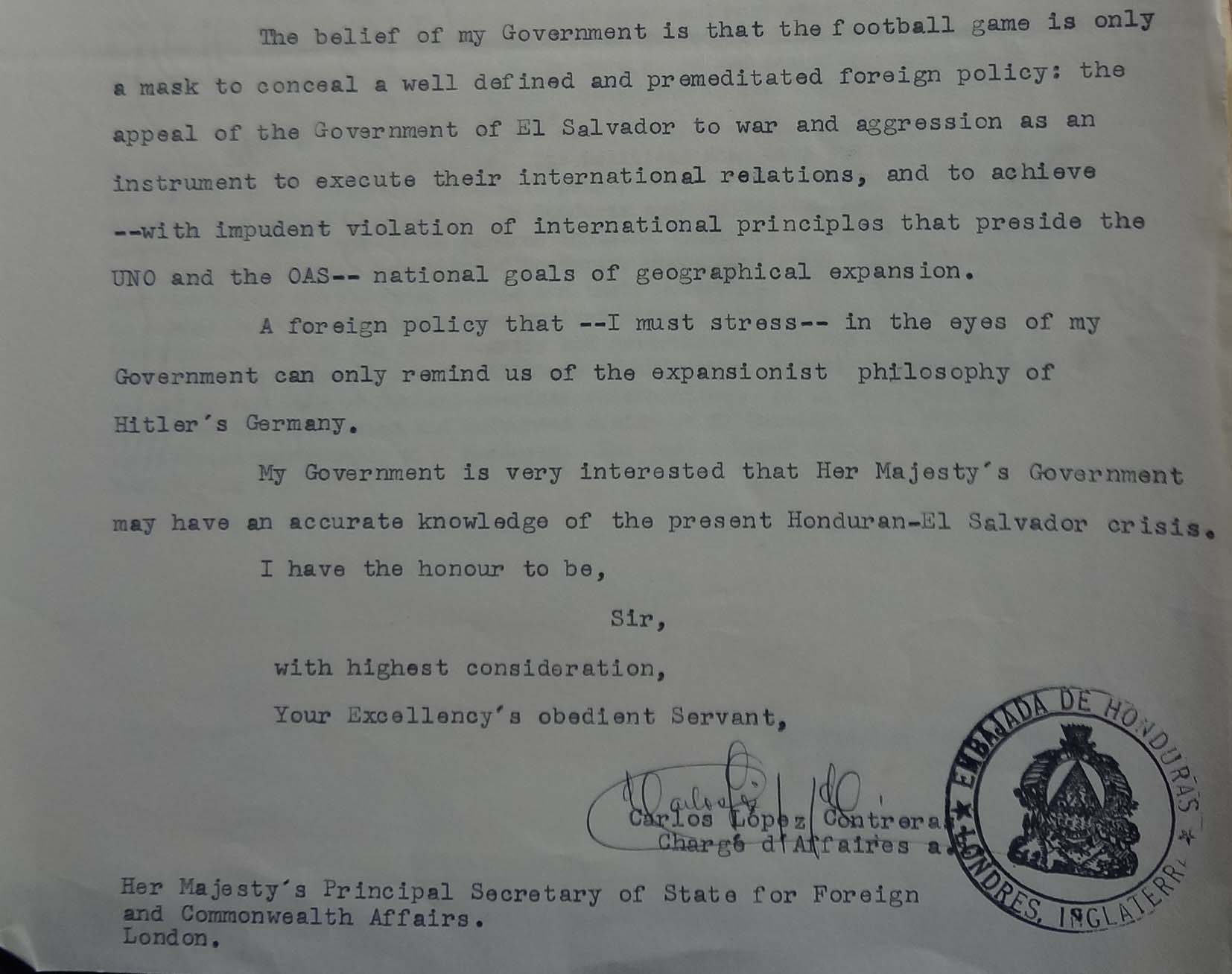

On 4 July, propaganda went up one notch yet again when, in a letter to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the Honduran Chargé d’Affaires in London compared El Salvador to Nazi Germany. The belief of his Government, he wrote, was that they were trying to ‘achieve (…) national goals of geographical expansion. A foreign policy that – I must stress – in the eyes of my Government can only remind us of the expansionist philosophy of Hitler’s Germany’ (FCO 7/1210).

Letter from the Honduran Chargé d’Affaires to the FCO, 4 July 1969 (catalogue reference: FCO 7/1210)

Around the same time, both Honduras and El Salvador reported violations of their airspace, and Salvadoran troops gathered on the border.

On 28 July, the FIFA observer issued an official statement

categorically affirming that the Salvadorean public at the Flor Blanca Stadium before, during and after the match against Honduras had behaved correctly and respectfully towards the National Anthem and symbols of Honduras, and that the Honduran players had subsequently left the country without molestation (FCO 7/1211).

By that time, however, it was too late.

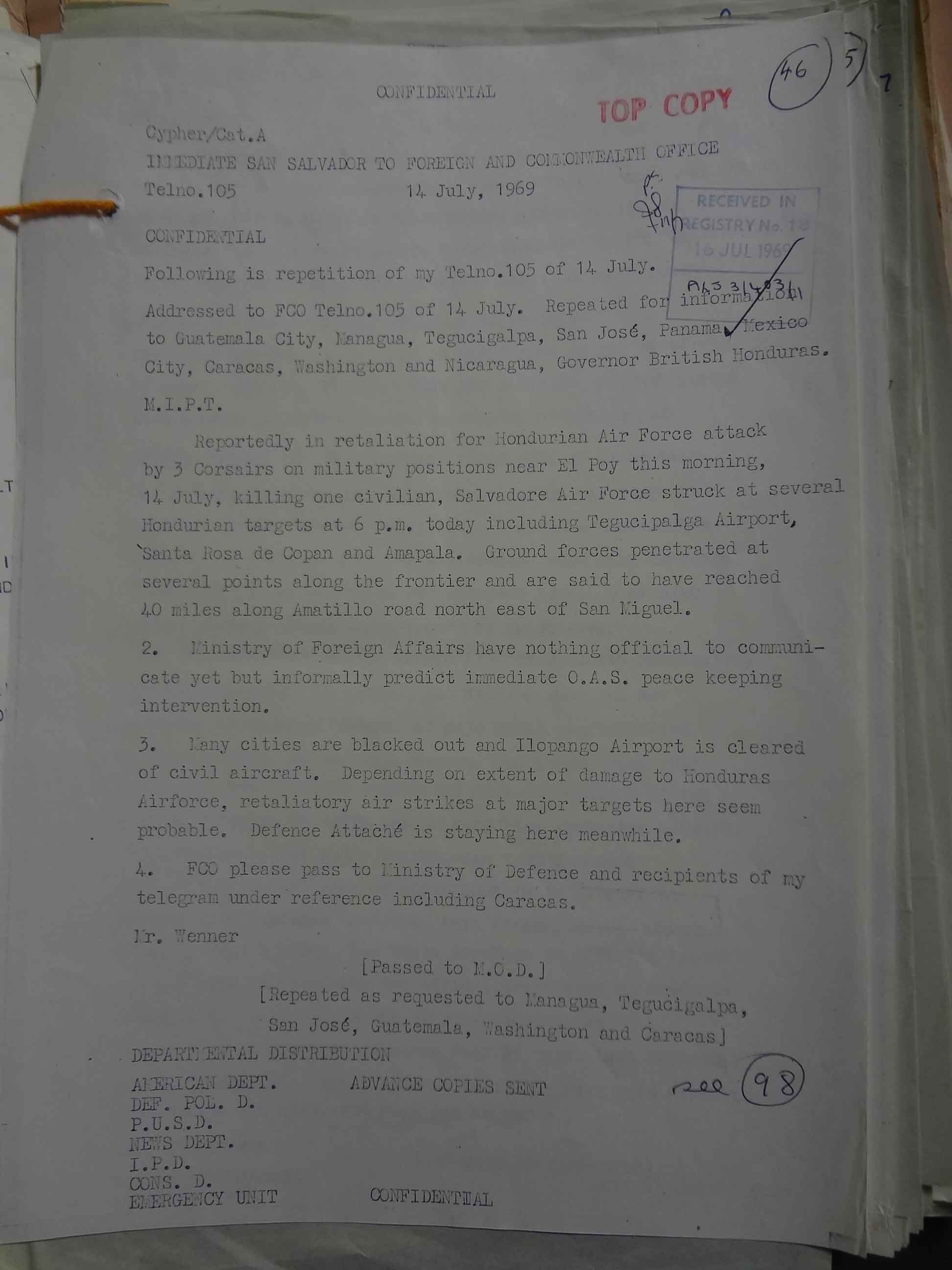

On 14 July 1969, around 18:00, the Salvadoran Air Forced attacked the airport of Tegucigalpa and bombed seven other towns: Nueva Ocotepeque, Santa Rosa de Copán, Nacaome, Amapala, Choluteca, Juticalpa and Catacamas. Salvadoran troops moved forward into Honduran territory (FCO 7/1588). In response, Honduras bombed military targets in El Salvador – a petrol refinery at Acajutla, the oil installations at Port Cutuco, and the military base at the Ilopango airport (FCO 7/1210).

The Organisation of American States, which had despatched mediators from Costa Rica, Guatemala and Nicaragua at the end of June, managed to negotiate a ceasefire, effective from 22:00 on 18 July. The war had lasted almost exactly 100 hours (FCO 7/1588).

The ‘Football war’ ended officially at 22:00 on 22 July, but an uneasy state of uncertainty remained. El Salvador finally agreed to withdraw its troops on 2 August 1969. Michael Wenner wrote a few days later that ‘the struggle was brief but internecine. Each side was prodigal with accusations and counter-accusations of all sorts of excesses on the part of the other’ (FCO 7/1211). Because of the level of propaganda in both countries, the return to normality wouldn’t be swift, nor easy. There were several frontier clashes in 1970, which were given ‘parochial publicity’ by both Honduras and El Salvador. An agreement was eventually reached on 4 June 1970 (FCO 7/1591).

The Salvadoran President inspecting the troops in Nueva Octopeque, captured by the Salvadoran army, July 1969 (catalogue reference: FCO 7/1211)

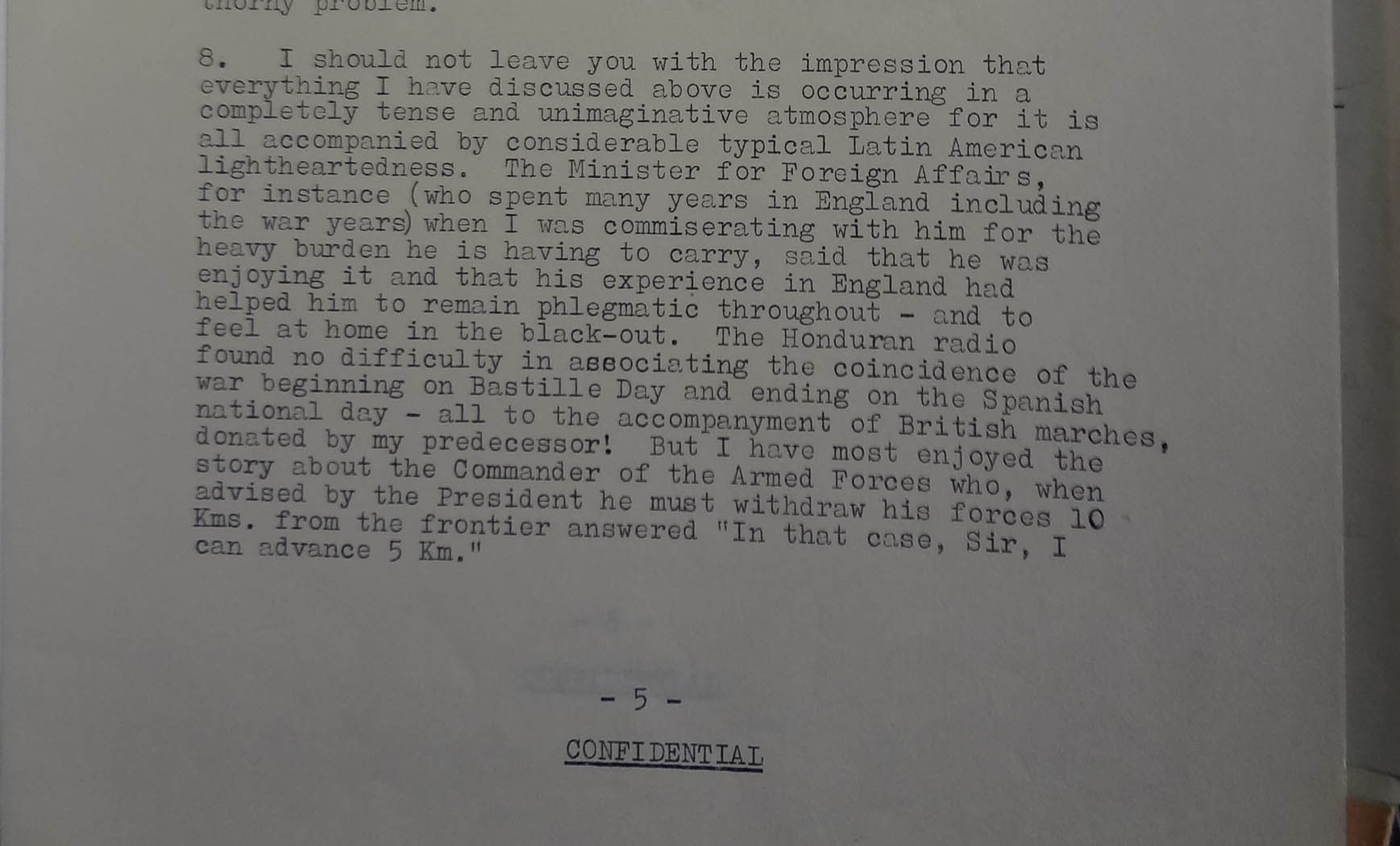

Lawrence L’Estrange wrote from Tegucigalpa on 23 July:

There was considerable typical Latin American light-heartedness (…). I have most enjoyed the story about the Commander of the Armed Forces who, when advised by the President he must withdraw his forces 10 kms. from the frontier answered: ‘In that case, Sir, I can advance 5 km.’

His First Secretary commented a few days later: ‘While it has had its farcical side (…) it has not, of course, been quite so amusing on the ground here’ (FCO 7/1211).

Indeed, between 4,000 and 6,000 people died (mostly civilians), 15,000 were wounded, and between 60,000 and 130,000 ‘undocumented’ Salvadorans were deported back to El Salvador. The conflict also put an end to the Central American Common market, and took its toll on El Salvador in particular. An FCO official noted on 2 June 1970: ‘At this rate of population growth, the place is bound to go pop one day’. A terrible civil war erupted in October 1979 and lasted 12 years.

On the football stage, because of the conflict, both Honduras and El Salvador were disqualified from entering the 1969 Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football (Concacaf) Championship qualifications. On a more positive note, El Salvador played in the World Cup for the very first time in 1970 and, as we’ve seen a few weeks ago with our friends from Panama, it’s quite a big deal. Sadly, the Salvadoran team were also, I am told, the first team to be knocked out at Group Stage without scoring a single goal.

A Treaty of Peace was finally signed in Lima on 30 October 1980, and El Salvador beat Honduras 2 – 1 on 23 November 1980, the first game they had played together since 1969. As we have seen in the last few years, there’s a fine line between football and politics.