A bedraggled and weary English army of over 9,000 men made its way across the river Ternoise, Picardy, Northern France on 24 October 1415. They had been marching for three weeks since leaving town of Harfleur, and were in a desperate bid to reach English-controlled Calais before French forces succeeded in preventing them.

As English and Welsh soldiers climbed the hill beyond the river, towards the town of Maisoncelles (about 45-50 miles south of Calais), they beheld a terrifying sight. The French army, numbering perhaps between 15,000 and 20,000 men, had outmanoeuvred Henry’s forces. They blocked the route northward only a few miles away, between the villages of Tramecourt and Azincourt.

An unnamed chaplain who rode with the army described Henry’s reaction when one of his captains, Sir Walter Hungerford, lamented that they didn’t have a further 10,000 archers to help their cause against such a mighty French army:

‘That is a foolish way to talk because by God in Heaven upon whose grace I have relied and in whom is my firm hope of victory, even if I could I would not have one man more than I do…do you not believe that the Almighty, with these humble few, is able to overcome the opposing arrogance of the French who boast of their great number?’ [ref] 1. ‘Gesta Henrici Quinti’, p.79, cited in Ian Mortimer, 1415: Henry V’s Year of Glory (London, 2009), p.424[/ref]

Henry began to deploy his forces, although the battle would not be fought until the following day: 25 October, the Feast of St Crispin and St Crispinian.

Getting ready to fight

There is an account of the battle discreetly buried among the pages of a late 16th century treatise on warfare, which draws on examples and counsel from medieval and antiquarian sources (catalogue reference: SP 9/36). This is most likely an extract from the published chronicle of Raphael Holinshed (1520-1580) describing the battle.

As the English and French drew up for battle the chronicler takes up the story:

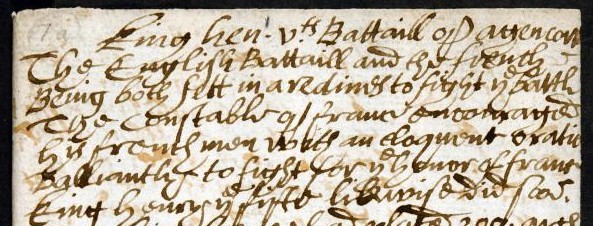

‘The English Battail and the French being both sett in a redines to fight [th]e battail the constable of France encouraged his Frenchmen with an eloquent orat[r]ie valliantly to fight for [th]e honor of France King Henry [th]e fifte [fifth] likewise did sooe.’

The battle of Agincourt account copied in a 16th century treatise on warfare (catalogue reference: SP 9/36)

Several accounts of the battle, including Shakespeare’s famous interpretation, have Henry rousing his men with a compelling speech – but unfortunately we will never know what the king may have said to raise the courage and spirit of his troops.

The English were deployed in three battles (groups) of men-at-arms, most likely arranged in a line side by side, with divisions of archers positioned either at the sides or between each battle. King Henry had ordered his archers to cut and fashion stakes at least five to six feet in length to help defend against possible French cavalry attacks, as the account describes:

‘[th]e kings battels being weake in comparison of ye French he feared lest [th]e Frenchmen would compasse him a boute hath therfor caused stakes bound w[i]t[h] iron sharp at both endes of [th]e length of 5 or 6 foote to be pitche[d] before the archers to [th]e ende that if the Barbed horses ran rashly on them they might be gored in thir belys…’ (catalogue reference: SP 9/36)

The French army led by the Marshal of France, Boucicaut, and the Constable of France, Charles D’Albret, was also divided into three battles, with a vanguard in front, the main battle in the middle and a rearward battle in reserve.

The stage was thus set for battle: archers restrung their bows while men-at-arms, all dismounted, gripped their weapons tightly, as unfurled banners flapped gently in the wind. Then Henry ordered his army to advance to attack.

The battle

English archers marching within range of the French loosed their arrows, provoking French cavalry charges. These were repulsed in a storm of arrows and slowed by the thick, churning mud caused by earlier wet weather. As their comrades on horseback thundered in retreat from the English line, the massed ranks of French men-at arms fighting on foot from the vanguard and main battles pressed forward to attack.

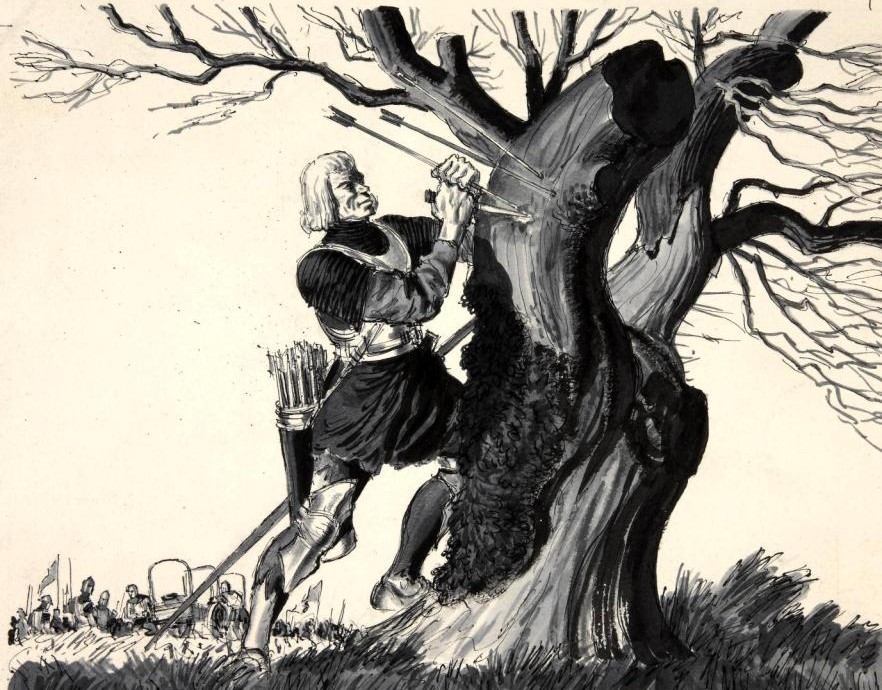

Archers fire volleys into the oncoming French men-at-arms (catalogue reference: INF 3/391)

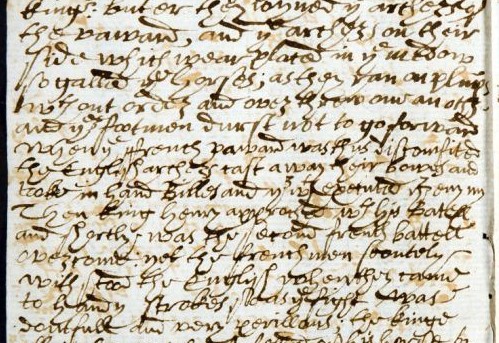

Although events of the battle are blurred, simplified and confused in many chronicle accounts, we pick up the essence of what happened in the chronicle account in SP 9/36:

‘….[th]e archers on their side… so galled [th]e horses [of the French cavalry] as they ran on plump w[i]th out order and over threw one an other and [th]e [French] footmen durst not go forward when [th]e French vaward [vanguard] was thus discomfited the English archers cast away their bowes and tooke in hand billes and [the]r w[i]th executed [th]e enymy. Then King Henry approched w[i]th his Batell and shortly was the second French battell overcome: yet [th]e Frenchmen stoutely with stood the English when they came to hand strokes so as [th]e fight was doutfull and very perilous…’

The open terrain on which the French men-at-arms advanced narrowed towards the English position, counteracting their numerical superiority. The press of men eager to strike at the English enemy forced heavily armoured men-at-arms to the ground, where they were vulnerable to an English arrow or sword, or to drowning in the mud. When the archers ran out of arrows, they joined in the fray with mallets and short swords. The fighting was fiercest around the English vanguard led by the Duke of York, who was himself killed along with 90 men of his retinue.[ref]2. Ibid., pp.441-442 [/ref]

After about three hours of intense fighting the English line was still intact. Attacking French forces had been decimated, and many had been taken prisoner. The battle was not over, however. The remnants of the French vanguard and main battles regrouped ahead of the French rearguard which had not committed yet to the fight, and remained a major threat to Henry’s exhausted forces. A furious attack had also been made on the English baggage train, but was driven off. Henry, perhaps fearing the French could launch a further attack, gave the controversial order to kill all but the most noble of captured French prisoners.

As the prisoners were being tragically butchered, Henry attempted to ready his forces once more for a second confrontation:

‘Then the king caused his horsemen to feche a compasse aboute and to wyn w[i]th hym a gainst the French rearward, which was strongest of men, the French perceveing his intent and being amazed brake their aray and ran a way to save their lives…’

It must have been to Henry’s relief that the French had no further stomach for a fight that day. His men were almost spent and Henry himself remained alert to the lingering threat to his army by French reinforcements; but victory was indeed his.

Though Agincourt stands in English history as Henry V’s famous victory against the odds, the courage of both French and English soldiers on that day should be equally esteemed and those that lost their lives on both sides commemorated respectfully.

As part of the 600 Anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt, The National Archives is providing a series of events, blogs and exhibitions. You can view documents in our online exhibition on the campaign and battle.

[…] A bedraggled and weary English army of over 9,000 men made its way across the river Ternoise, Picardy, Northern France on 24 October 1415. They had been marching for three weeks since leaving town of… Go to Source […]

Just want to revise the estimates of the French forces present at the battle which based on recent scholarly research is more likely to be between 12,000 and 15,000 men.

The description seems to be quite accurate. I’m still following the blog.

An amazing battle for both sides.

We can only try imagine what it must have been like on the field that day.

It reminds me how soft men have become, generally ( not the seasoned soldier, if there is such a person now)

Two of my family were there that day.

Thank you for an interesting and historical read.

I have read quite allot about this battle and am an Archer myself. But playing in all Reality.

Still practice on a Sunday though.