At The National Archives we have been proud to put women at the centre of much of our programming this year. But the commemorations are not over yet!

Cover of the Representation of the People Act, 1918. Catalogue ref: C 65/6385

It’s 100 years since the 1918 General Election: the first election in which some women were able to vote and also stand for election to Parliament. For the first time, women truly had a political say on a national level. Just imagine how the women, and men, voting for the first time must have felt. Was it excitement? Nerves? Relief? And what of the women under 30 or who didn’t meet the property qualification? Many of them had campaigned hard in suffrage struggles or dominated the female workforce during the war – how did they feel?

After 50 years of campaigning to get the vote, the Representation of the People Act of February 1918 enabled women over 30 who met a property qualification to vote. This Act also opened up the electorate to millions of working class men, many of whom would have previously been disenfranchised. By the end of 1918, women were also able to become MPs on the same terms as men, in many ways an even more radical piece of legislation. For many, the rate of progress was much quicker than they had expected.

In this blog post, and my next one, I am going to explore the impact this general election had on the women who participated – both as voters and as candidates.

Women as voters

Eight months after some women became eligible to vote, they were able to enact that right, alongside many working class men also voting for the first time. The election had been quickly called after the announcement of the Armistice, as elections had been essentially suspended over the duration of the war: it was long overdue.

It commonly became known as the Victory Election, because of the recent conflict. But equally this ‘victory’ could be seen as relating to the enfranchisement of women – women were set to be about a third of the electorate. 8.4 million women now had the right to vote and it was first time the electorate had a working class majority.

The December 1918 election was clearly a landmark moment. It was about so much more than just the passing of legislation; there were real women all over the country walking into polling stations and exercising their democratic right to vote.

Of course, women’s voices had not always been absent from national politics. It was under the terms of the Great Reform Act of 1832 that women had been barred from voting, with voters being formally defined as ‘male persons’. Nevertheless, millions of women were now about to vote.

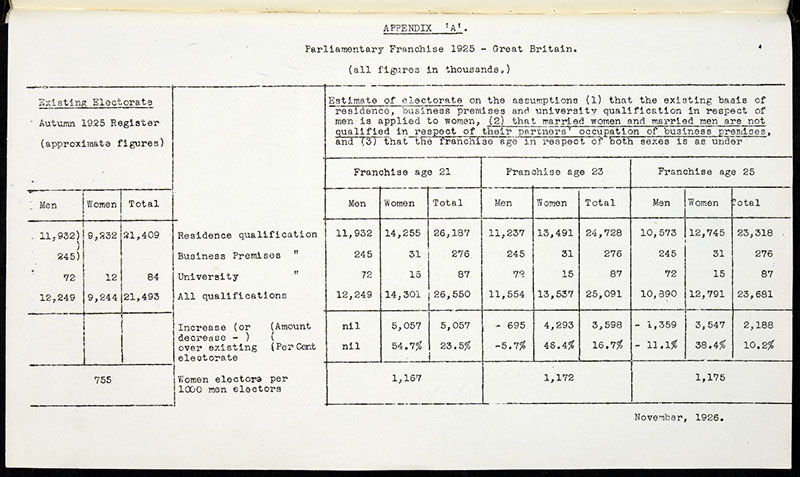

Before the passing of the 1928 Equal Franchise Act there were many intense cabinet discussions. Politicians feared the impact of an electorate with a female majority, and discussed giving women over 25 the vote, rather than on equal terms with men. Reference: CAB 27/336.

As suffragist Ray Strachey noted, the Act had not been on the statute a fortnight before the House of Commons, shockingly, discovered that every bill had a women’s side. [ref] ‘The Cause’: A Short History of the Women’s Movement in Great Britain, Ray Strachey. 1928. [/ref] Suffrage campaigners urged women to vote. In the weeks leading up-to the December election, Margery Corbett Ashby, suffragist and electoral candidate, said in the NUWSS publication ‘The Common Cause’:

I would rather you women gave your votes against me than that you should not vote at all. In any case vote ‘as if on you alone hung the issues of the fray.’ [ref] ‘The Common Cause’, 13 December 1918. [/ref]

Newspapers were rife with speculation about the ‘women’s vote’ – what difference would it make? ‘The Common Cause’ noted: ‘Nobody, not even the most experienced political organiser, has the remotest idea of the direction in which the thoughts of the women voters are turning.’ [ref] ‘The Common Cause’, 6 December 1918. [/ref] Discussions in Home Office and Treasury files show that that practicalities were the primary concern of government: administering boundary changes, updating electoral registers and figuring out how they were going to store the huge amount of extra ballot papers.

The election was held on a rainy Saturday very close to Christmas; logistically this often meant women had to organise childcare, and for some they had to find time around work to vote. Discussion in Edwardian newspapers described how, despite the wet weather, many mothers managed to carry their babies to the polling station. Women canvassers offered, where possible, to look after children.

The experience and process was new to women; suffrage newspapers advised women on how to vote, explaining that it was essential to mark a cross ‘x’, not your name or initials.

Despite the clear significance of the election, it was the lowest recorded election turnout. In many ways, this victory, so long in the making, had been overshadowed by war.

The vote count was delayed until 28 December so that the ballots cast by soldiers overseas could be included. Its impact was therefore not felt immediately. The coalition won the election comfortably, with the Conservatives dominating. However, this is rarely what this election is now remembered for.

The rate of change

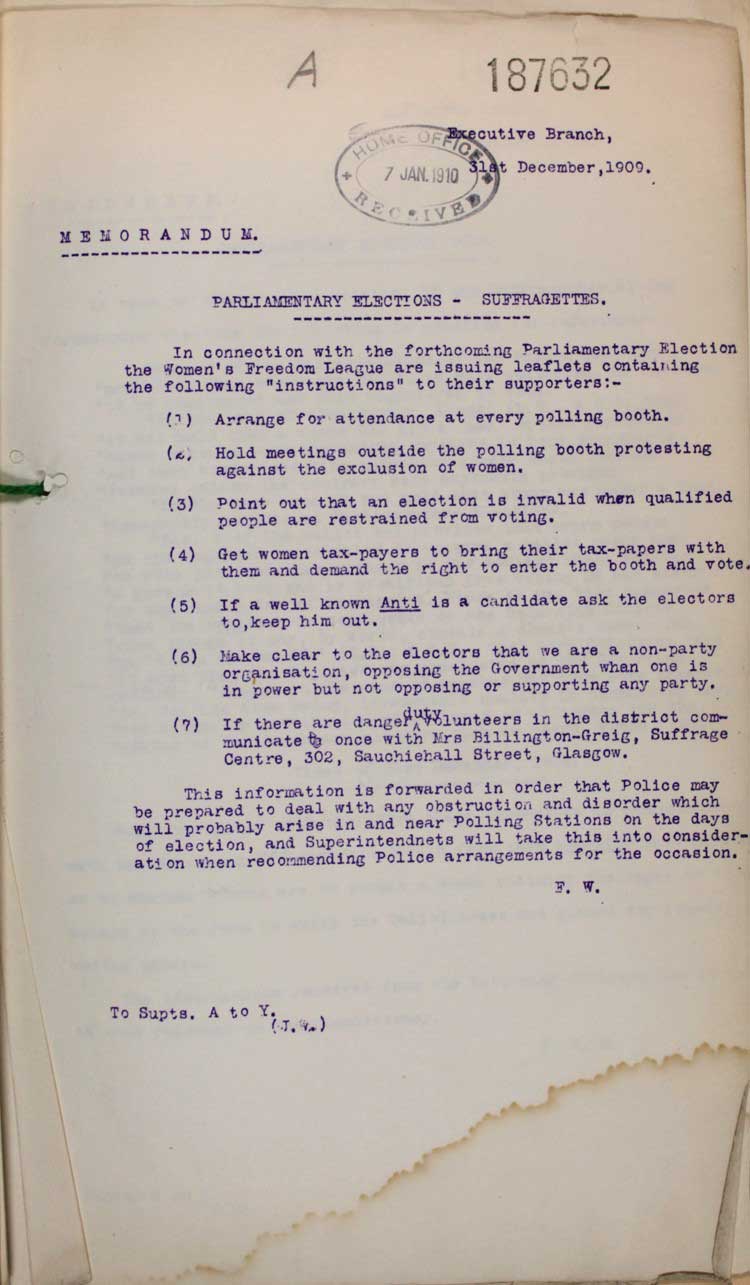

In the build up to the 1910 election the Women’s Freedom League are issued leaflets containing the following ‘instructions’ to their supporters – how different this was from the 1918 election! Reference HO 45/10597-187632.

In December 1909 the Women’s Freedom League, the militant but non-violent women’s suffrage society, issued a memorandum, listing instructions to their supporters in the 1910 election. This included:

- Arrange for attendance at every polling booth

- Hold meetings outside the polling booth protesting against the exclusion of women

- Point out that an election is invalid when qualified people are restrained from voting

It reads in stark contrast to the actions that women were taking to vote themselves in this 1918 election, less than a decade later – legitimately walking into these polling stations, and voting themselves.

How much difference did the enfranchisement of women really make? The very act of (some) women being able to vote was a huge step towards equality; however, the battle had now really started to instigate legislative changes for the better.

Next week, read about women standing as electoral candidates in the 1918 election.

I hopefully look forward to seeing The National Archives doing such a positive series on men!, there is equality and then there is equality and women had more equality, in for example infanticide cases than men as pointed out by the Home Secretary. If the Suffragettes achieved so much why did they not have more women Members of Parliament?.

Regarding infantacide, there are well documented medical conditions that can affect a woman post partum, which can lead to extreme behaviour, not to mention societal pressures impose on women by puritanical patriarchy. I refer you to several writings by Dr Daniel Grey for elaboration. As far as female members of parliament are concerned, I refer you back to the patriarchy (old boys club) which, by the way, women are still fighting today.

The war killed 12% of the ranks and 17% of the officer class, yet the National Archive felt it best to centre women rather than the end of the war? Male disposability at its best Women were so grateful to the men for their sacrifice it changed women’s politics to the Right It’s much less easy to explain why women didn’t exercise the right to vote