Thursday 26 April 2018, 14:00

Thursday 26 April 2018, 14:00

Suffrage 100 – Suffragettes in trousers: male support for women’s suffrage in Britain

On 6 February 2018, celebrations were held across Britain to commemorate the centenary of the 1918 Representation of the People Act, which gave some women the right to vote for the first time. While this was pivotal for women’s suffrage, it was also an important milestone for men’s suffrage. Prior to the Act, property qualifications had been used to control the electorate, excluding most working-class men from voting. Despite attempts to satisfy concerns of democratic inequality, the Reform Acts of the 19th century continued to avoid universal manhood suffrage. The fourth and final Reform Act of 1918 was the first time male suffrage was achieved.

The British electoral system of the early 19th century was viewed as extremely unfair and in need of reform. In 1831, only 4,500 men could vote in parliamentary elections, out of a population of more than 2.6 million people. There were also concerns about parliamentary representation, as there were rotten boroughs, such as Dunwich in Suffolk, who could elect two MPs when they only had a population of 32 in 1831. In contrast, large cities, which had expanded over the previous century, including Manchester and Birmingham, had no MP. With increased pressure for electoral reform, parliament inevitably had to make changes.

The Great Reform Act of 1832 was a response to increasing criticism of the electoral system. Government began to fear that, if reform did not take place, then a revolution would ensue, as it had in France in July 1830. For example, a petition from the people of South Shields requested reform as they felt they deserved a right to vote and wanted more parliamentary representation. 1

The petition was created by ‘merchants, manufactures, shipowners and other inhabitants of the town’, but these groups would continue to be excluded from voting even following the 1832 Act. 2

Despite what its title may suggest, the Act did not signify great change to the electoral system. Most working men still could not vote, with the franchise being restricted by property qualifications. The continuing discrimination against working class men within politics merely angered many and led to the formation of groups for universal manhood suffrage.

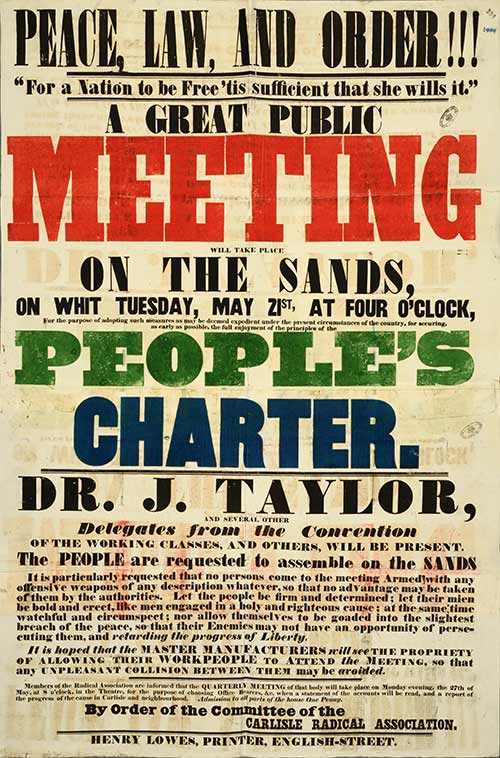

The Chartist Movement developed after the 1832 Reform Act failed to extend the vote beyond those owning property. Its members were typically from the working class and their 1838 People’s Charter was established by the London Working Men’s Association. The petition had six demands:

- Universal suffrage

- The secret ballot

- Annual Parliamentary elections

- No property qualifications

- Equal voting districts

- Payment of Members of Parliament 3

Chartist movement poster for Carlisle, 1839. Catalogue reference: HO 40/41

Despite numerous attempts to present the petition to the House of Commons, the Charter continued to be rejected, which only encouraged unrest and violent behaviour. In 1841, during the canvassing of candidates for the forthcoming election in Carlisle, a letter to Sir Charles Napier recounts that ‘Candidates were insulted and pelted, [and] on the day of nomination a riot took place’. 4

In the short term, the Chartists were unsuccessful as their radical actions did not immediately drive electoral reform. Their militant methods could be viewed as undermining their campaign, which is arguably similar to the actions of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Nevertheless, militancy in both cases successfully publicised the movements and both groups eventually had success. The Chartist movement declined after their third and final petition was rejected in 1848, but new groups continued to fight for manhood suffrage.

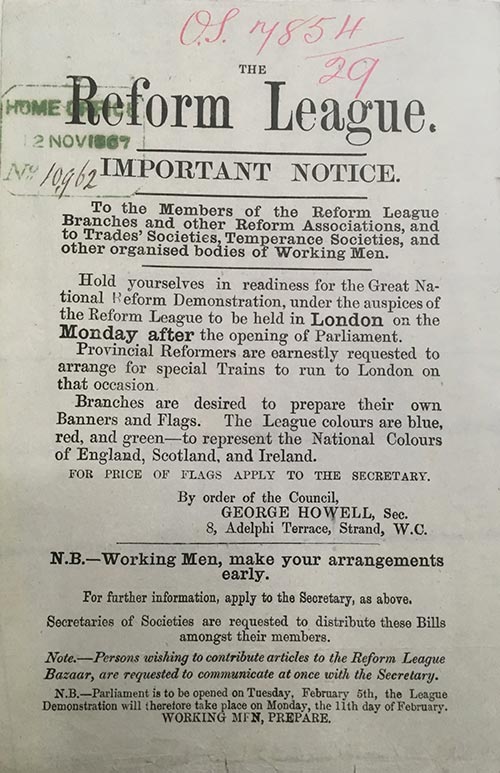

Notice for The Reform League, 1867. Catalogue reference: HO 45/7854

Various other groups were established, including the National Parliamentary and Financial Reform Association in 1848 and the National Reform Union in 1864, but these were short-lived and not as prominent as the Chartists. However, one group that made a big impact on political reform was the Reform League, which was founded in 1865. Ex-Chartists joined the League along with urban artisans. It also welcomed ‘other Reform Associations… and other organised bodies of Working Men’ to its demonstrations outside Parliament, such as in February 1867. 5 Yet, it is clear the Reform League were not as dedicated to universal male suffrage as the Chartists. The League dissolved within two years after the Second Reform Act of 1867, evidently satisfied by the increase in enfranchisement. Although, the League had achieved more than the Chartists, its members were clearly not as concerned with universal male suffrage.

The influence of suffrage groups, including the Chartists and the Reform League, encouraged the Second Reform Act of 1867. However, Parliament remained resistant to universal manhood suffrage and the Act, like its predecessor, included property qualifications as a means to control the electorate. The Act partly enfranchised the urban male working-class, granting the vote to those who owned houses in boroughs or lodgers who paid rent of £10 a year or more. while this doubled the electorate in England and Wales from one to two million men, universal manhood suffrage remained a distant idea. Even after the Third Reform Act in 1884, there was still a reluctance to provide all men the right to vote. It only partly overturned the previous Act by establishing a uniform franchise throughout the country. Moreover, it extended the same voting qualifications that existed in towns to those in the countryside. Yet, these attempts to extend the electorate were futile at ensuring universal manhood suffrage. However, with the rise of women’s suffrage, the fight for male suffrage was refuelled and presented a new angle for battling the resistance of Parliament.

It appears that as women’s suffrage groups became more prominent, there were fewer suffrage groups that specifically focused on male suffrage. It is likely that some men began to support women’s suffrage groups as they viewed it as a route towards universal manhood suffrage. The Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage was founded in 1907 by a group of largely middle class, left wing radicals. Henry Brailsford, the founder of the group, had been encouraged to actively participate in the suffrage campaign by his wife, Jane Esdon Brailsford – a militant suffragette. Men were increasingly interested in the suffrage movement and wanted to support votes for women, as it would inevitably ensure votes for all men.

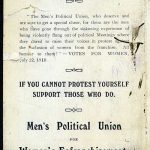

While most suffrage societies allowed male members, the WSPU did not. Consequentially, the Men’s Political Union (MPU) was formed in 1910 as a militant male counterpart to the WSPU. Members of the group participated in similar radical actions to their female equivalent, such as Hugh Arthur Franklin who attempted to whip Winston Churchill, the home secretary at the time, at the ‘black Friday’ suffrage demonstration on 18 November 1910.

- Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement membership card which details the union’s aims and the methods they used to support votes for women. Catalogue reference: CRIM 1/149/3

Gender did not dictate the actions of the militant suffrage supporters and in prison Franklin went on hunger strike and was supposedly force fed 100 times. However, unlike the WSPU, the MPU remained active throughout the First World War and eventually federated with the East London Federation of Suffragettes to create the Worker’s Suffrage Federation. Although we cannot assert one definitive reason for why the Representation of the People Act was granted in 1918, the efforts of the suffrage groups played an important role in pushing for this next step in electoral progress.

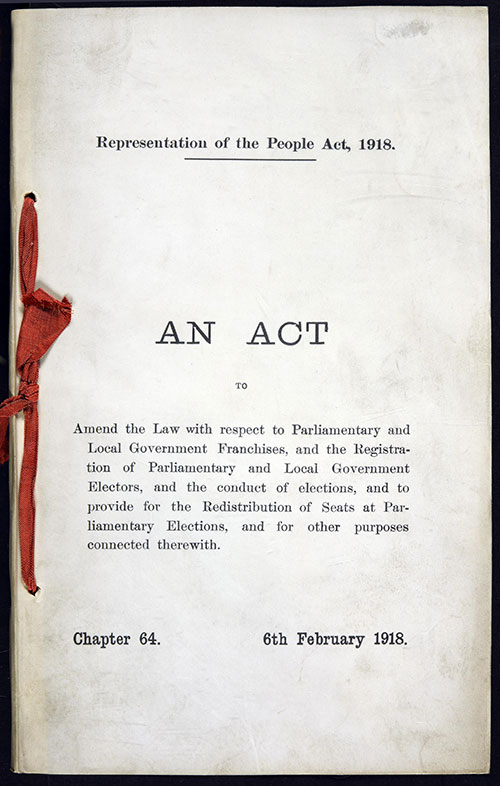

A man shall be entitled to be registered as a parliamentary elector for a constituency… if he is of full age and not subject to any legal incapacity. 6

The 1918 Representation of the People Act symbolised the end of the long and weary path for universal male suffrage. Manhood suffrage may have been removed as the focus for electoral progress as women’s suffrage became more prominent, but it always remained an issue for the electoral system. Although the Chartist Movement had been unsuccessful, by the time of the Fourth Reform Act, nearly all their aims had been achieved, except for annual parliamentary elections. The period between the first and the fourth Acts witnessed minor victories for male suffrage, but it was the final reform and the introduction of women to the electorate that won all men the right to vote.

Cover of the Representation of the People Act 1918. Catalogue reference: C 65/6385

The Citizens project is led by Royal Holloway, University of London, and charts the history of liberty, protest and reform from Magna Carta to the Suffragettes and beyond.

Elena Rossi is a Citizens Project intern.

Notes:

From 1918 men could only vote if they were aged 21 years old, something which took another 51 years to be changed to 18 years (in 1969) and even today there is opposition to letting 16 and 17 year olds to vote (as Scotland allowed for the Scottish Referendum). It is concerning that it has taken 2 months since TNA celebrated Women’s suffrage for TNA to talk about men a lot of who died in war before they got a vote.

In fact men serving in the forces could vote at the age of 19 (the position of those already discharged who were under 21 was less clear).

Is the wording in the second paragraph correct when it says there were 2.6 million people? According to the 1831 census there were 16.5 million people and 2.85 million households

This briefing from the House of Parliament says there were more than half a million male voters in 1831

http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/RP13-14#fullreport

I found this very interesting & will use this research in an assignment I am doing at the University of Southern Queensland (Australia) online. It is an argumentative assignment from the enlightenment to male & female suffrage movements through to through to the struggles for Gay & Lesbian rights in the world. It is for the course The History of Western Ideas. Thank you & have fun! Heather D.

I noticed that too, Diana. The 19th century was one of incredible population growth due to medical and dietary advances that significantly reduced the death rate, particularly the infant mortality rate. The census of 1801 indicated a population of circa 9 million for England and Wales which by the 1901 census had risen to circa 38 million, an increase of around 320% in 100 years.

The 2.6 million and 4,500 refers to Scotland and not England & Wales

I wanted to find out if police officers were excluded from voting at any time and if so when this exclusion was removed

There were over 23,000 voters in Yorkshire for the 1807 parliamentary election, so the figure of 4,500 men eligible to vote is simply not true. The Yorkshire poll book for the 1807 election was published and is available on line at https://archive.org/details/countyyorkpollf00unkngoog