As a scholar and artist, one of the things I’m most interested in is process. The process of making things. The process of research. The process of writing.

So often, we experience the final products of things – a book, presentation, article or film. What’s often sidelined is discussion of how we actually go about our work. All those messy drafts. Early mornings or late nights analysing data. Days scouring archives with hopes of finding that one groundbreaking document. This blog offers a glimpse into some extraordinary finds among the design records at The National Archives.

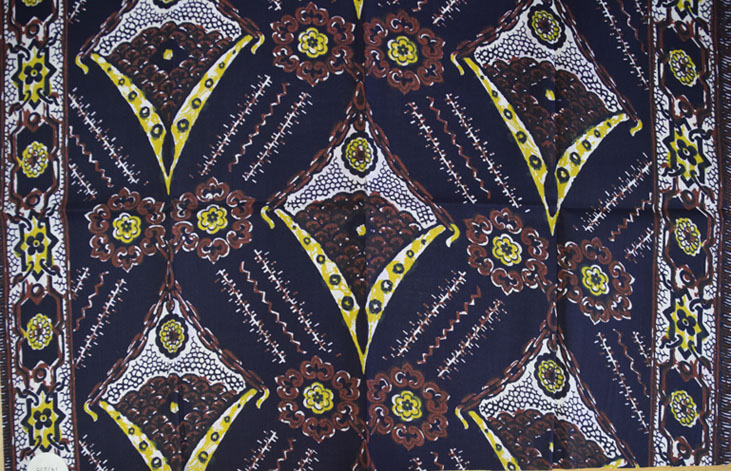

Details of UK fabric samples designed for export to Africa and held at The National Archives.

Earlier this year, my PhD dissertation research led me to studying designs registered in the UK for copyright (see online guide) now held at The National Archives. These designs include various objects made in metal, wood, cloth, and glass. A total of around 3 million designs were registered for copyright from 1839-1991. In short, an extraordinary archive with vast scope for research. Surprisingly, few scholars have conducted in-depth studies of these records.

Registered by Calico Printers Association, 3 January 1918 (catalogue reference: BT 52/3199/147275)

My research within the registered designs first pursued one line of enquiry: I was on a mission to find particular designs called adinkra symbols – graphic designs expressing proverbs, moral beliefs, and cultural values associated with the Akan of Ghana in West Africa. For at least 200 years, the Akan have hand-printed cloths with adinkra symbols to wear at funerals, festivals, political events or social gatherings. UK textile firms often incorporated African cultural imagery – such as adinkra symbols – to enhance the appeal of their fabrics marketed in Africa. By referencing adinkra symbols, UK textile designers contributed to changing the values and meanings of adinkra in Ghana, while also making adinkra accessible to a much wider audience across Sub-Saharan Africa.

Once I began this research, I quickly realized the potential of the material to tell an important history about the UK textile trade in Africa much larger than my initial focus. The number and quality of textiles designed for Africa that I found was overwhelming. And inspiring. Together with Julie Halls, the design records specialist – who coincidentally had just written a blog about textiles designed for West Africa – we developed a research project to investigate one area of the registered designs: the UK textile industry during the height of the trade in Africa from 1870-1970. The textiles illustrate how UK manufacturers and African consumers used cloth to negotiate power, identity, and colonial relations.

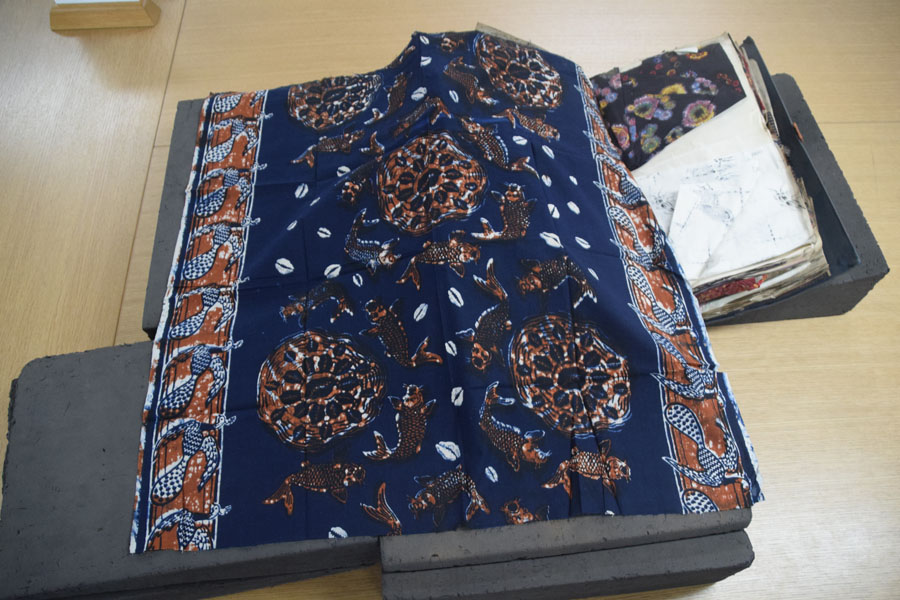

Registered by Calico Printers Association, 2 January 1929 (catalogue reference: BT 52/4059/27000)

Cloth was central to navigating economic, cultural, and political relationships between the UK and Africa. A specialised industry developed among UK textile manufacturers and merchants active in the Africa trade, especially those based in Manchester. They made textiles with various printing techniques attractive to consumers in Africa: machine-woven cloths, wax-prints, fancy-prints, and indigo-dyed cloths. These textiles are popularly known today as ‘African wax-prints’, despite the fact that they’re produced in the UK and have historical origins in Indonesia and the Netherlands.

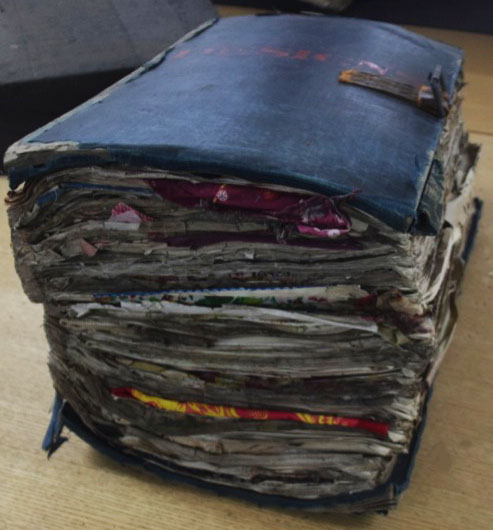

Bound volume of fabric samples (catalogue reference: BT 50/210)

This autumn I completed a pilot project, collaborating with Julie, to examine The National Archives’s holdings of textile designs destined for Africa, in preparation for larger project we hope to take forward. Initially, fabric samples deposited in the registry were placed in enormous bound volumes.

The volumes are remarkable objects. Designs were registered chronologically, with different merchants and manufacturers mixed within each volume. In other words, the UK textiles designed for Africa are pasted alongside other designs for the home market or other export destinations. The sheer number and variety of designs within a single volume offers a fascinating snapshot into the cultural, political, and industrial life surrounding the year of their making. From the early 20th century, the fabric samples are stored folded in boxes. For both the volumes and boxes, the research involved a two-step process: the fabric sample – labeled with a registration number – must be paired to a written entry in a separate book to identify the manufacturer’s information and registration date.

One of the main challenges in researching the registered designs is that only the early years, from 1839-1884, are fully catalogued. The pilot falls mostly in the uncatalogued area. Working with an uncatalogued archive entailed some obstacles. Finding what you’re looking for is very time consuming, with no guarantee that you’ll even actually find it. But in my experiences, the unexpected findings were more rewarding because they offered completely new understandings or challenged established ideas in scholarship.

Registered by F.W. Grafton & Co., May 1908 (catalogue reference: BT 52/64/2797)

Registered by Blakely and Beving, 26 March 1930 (catalogue reference: BT 52/4250/288525)

I was quite fortunate to find incredible materials in the registry day after day. But this kind of research to examine an uncatalogued archive requires a lot of patience. Some days were slow. At other times, I was scrambling to document boxes filled entirely with cloths for African markets. Researchers may find this process cumbersome and frustrating. I loved it. Admittedly, the thrill of discovery and not knowing what I would find as I opened each box or volume continued to excite me. It still does.

By the end of the pilot, I had accumulated many surprising finds that offer exciting new insights into UK design, trade, and colonial relations with Africa. Julie and I are now planning further, in-depth research into these textiles. What began as supplementary research to my PhD dissertation has potentially led to another project that will tell a 100 year history of the UK textile industry in Africa. My archival findings illustrate some of the unplanned, happy accidents from the research process.

My sincere thanks to the Modern Domestic Records Team, especially Julie Halls and Simon Demissie, for the opportunity to collaborate with them on this project.

That is some tiring work you did, but the catch is you liked it.

Loved reading your thoughts. Clothing as a method of archival research is a stunning roadway.