This is the first of three blog posts that will look at the establishment and development of the Ministry of Munitions in the early summer of 1915. Symbolising a dramatic shift in the approach to sustaining the war effort, the Ministry not only oversaw the development and production of the materials of war, but also had responsibilities for labour control and industrial output. Pre-dating conscription by a year, it marked a milestone on the path towards total war and – many argue – victory. However, its birth was not without controversy or opposition, and the immediate impact of its establishment continues to be debated.

The Ministry of Munitions owed its existence largely to the failure of the offensive at Neuve Chapelle in March 1915, the centenary of which begins next week. A shortage of high explosive shells became a scapegoat for a larger tactical failure in the first major British offensive of the war, initiating a bitter, finger-pointing media campaign – THE TRAGEDY OF THE SHELLS: LORD KITCHENER’S GRAVE ERROR, screamed the Daily Mail’s leading article on 21 May 1915. Subsequent analysis of the battle has come to much broader conclusions, but the ‘shell scandal’ – as it became known – not only contributed to the fall of Asquith’s Liberal government, but also to the appointment of David Lloyd George at the head of the newly created Ministry of Munitions.

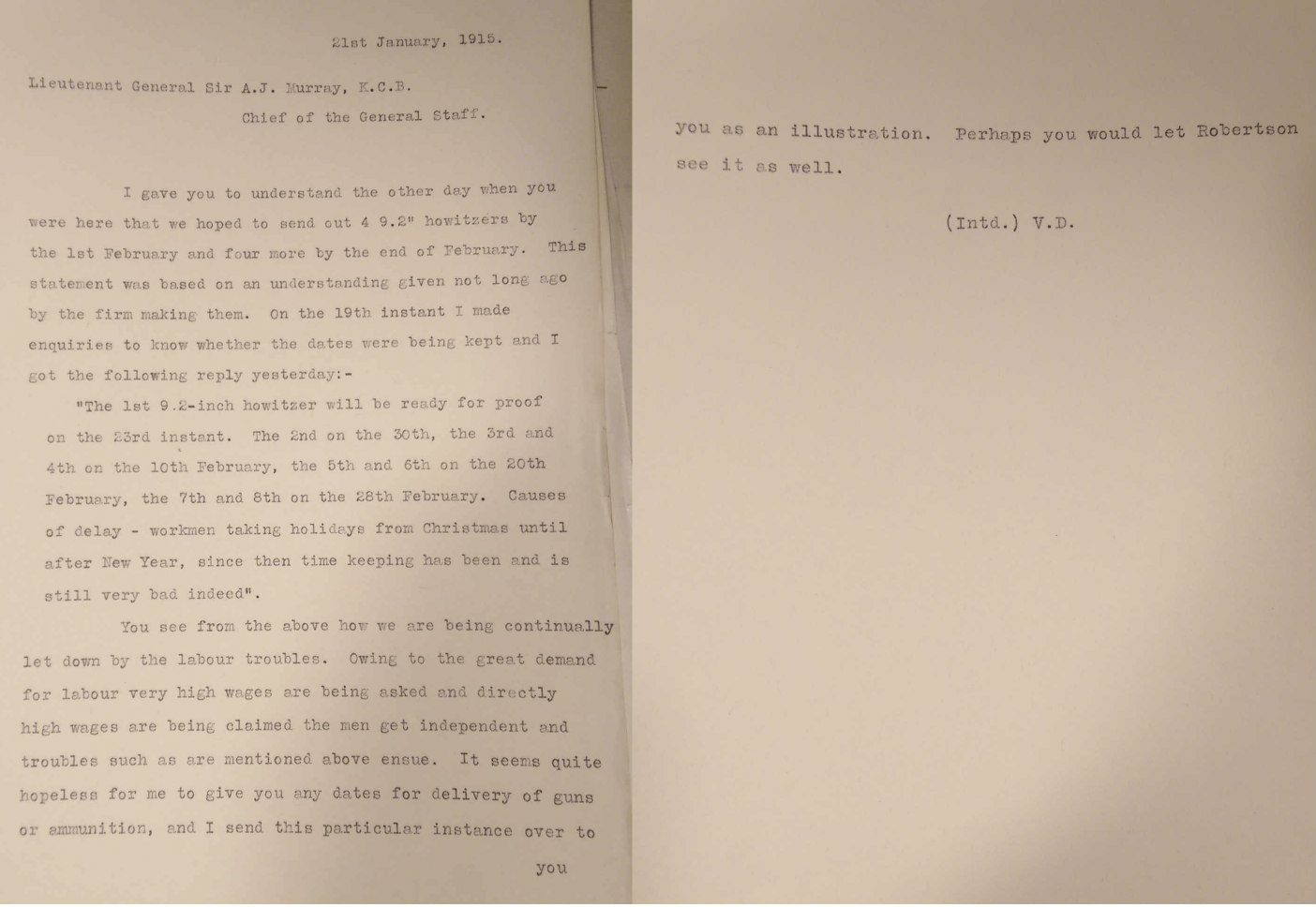

Despite the dubious nature of some of the claims made in the press and parliament, trouble with the production and delivery of munitions had been an issue since the beginning of the war.

We hold the official records of the Ministry of Munitions under the MUN department code, but to form a better understanding of the processes that fed the guns before 1915 we need to peruse the War Office files. Two casualties of the Shell Scandal were the Master General of the Ordnance (MGO), Major-General Sir Stanley von Donop, and the then Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener. In an attempt to answer the accusations of the press and politicians in the aftermath and defend the reputation of his – by the time it was circulated, late – superior, von Donop wrote an unofficial reflective memorandum entitled ‘The Supply of Munitions to the Army’ (WO 79/84). As the man ultimately responsible for the provision of equipment, he used the document to fall on his sword, but he did so to explain the problems presented at the outbreak of war and the situation the new Ministry would inherit.

The peacetime bureaucracy that sat behind the production and delivery of munitions at the opening of the war becomes immediately clear on reading von Donop’s notes. Supply had remained the responsibility of each service but, for the army, it was not simply down to the Master General of the Ordnance to make arrangements. Instead, the MGO provided the Director of Army Contracts (the Contract Branch of the War Office sat beneath the Financial Secretary) with the force’s requirements and he subsequently decided how these requirements would be met – either by the state ordnance factories or private industry. Orders could then be placed and were managed largely outside the MGO’s control. As a result, prior to 1915, the MGO was technically not responsible for any failure to deliver ordered munitions. Unfortunately, that meant the MGO could be and often was left waiting for promised deliveries with little power to expedite production; not necessarily a problem in peace but a potential disaster in war.

Letter from von Donop to Lt-Gen. Sir A. J. Murray. An example of the difficulty found in predicting delivery dates from contractors. Catalogue reference: WO 79/84

On top of this bureaucracy, von Donop identified two further troubling issues. Firstly, since the South African War, ordnance factory personnel had been reduced to a point at which they could cope with the needs of the expeditionary force but were unable to meet the demands of the expanded army. Secondly, few private firms were equipped to supply the armed forces and those that had held recent government contracts had had so few that investment in plant and skills was low.

As a result of this complicated and flawed system, the number of shells of all types reaching the British Expeditionary Force on the continent in 1914 and early 1915 was routinely short of what was promised, something that led to rationing long before the offensive operations in the spring of the following year (WO 161/23). Field Marshal Sir John French (commanding the BEF) claimed that the rate at which shells were arriving in late September 1914 allowed seven rounds per gun per day, while during the previous fortnight their average expenditure had been twice that (WO 79/84). The Commander of Royal Artillery for 2nd Division also recorded ammunition rationing for field guns in late October as a result of an order from I Corps (WO 95/1313/1).

The expeditionary force that crossed the Channel to fight on the continent in 1914 represented the bulk of the regular army not otherwise engaged in the stations of the British Empire. The increasing tempo and intensity of its operations meant the pre-war systems for supplying it with manpower and the materials of war were very quickly overwhelmed. With new formations being raised in the UK, more supplies were being taken from materials owed to the operational theatres, steadily increasing demand (WO 161/22). As von Donop’s collected correspondence demonstrates, despite repeated and increasingly exasperated requests for more and more materiel, the generals were met with the same response: nothing was being held back.

To sustain offensive operations it was becoming increasingly clear that something would have to change and that that change would need to be root and branch. Von Donop and his War Office colleagues would later argue that those changes were already in play by the time of Neuve Chapelle and the results would soon show; as will be demonstrated in next week’s blog post, however, they were not given a chance to prove it.