19th and 20th century coffeehouses in Cairo, Egypt, were an urban hub for revolutionaries, intellectuals, writers, middle- and upper-class men and women, workers, immigrants, and people from different ethnic, racial, and religious groups. Beyond the daily leisure activities they enjoyed there, coffeehouses were a place to get the news, discuss personal or public affairs, and even recruit and organise for political action.

Thus, tracing the history of Cairo’s coffeehouses can offer invaluable insights into Egypt’s social, cultural, and political history.

Indeed, Cairo’s coffeehouses appear everywhere in the historical record, from literature, to memoirs, journals, photographs, films, statistical yearbooks, travel accounts, and more. One unique source of information is state surveillance records. The state, whether Ottoman, Egyptian, or British-colonial, always had an interest in knowing what was going on, and what was said, in coffeehouses, as a measure for ‘public opinion’ that had the potential to turn into political action.

Tipped by a study of the popular music industry in Egypt, which referenced British intelligence reports mentioning popular songs spreading throughout Cairo’s coffeehouses during those year-long mass protests against British colonial rule, known to Egyptians as the 1919 Revolution,[ref]1.Ziad Fahmy, Ordinary Egyptians (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011)[/ref] I set out to The National Archives in Kew. There, I started a journey of reverse-engineering the history of the role of coffeehouses in Egyptian popular politics.

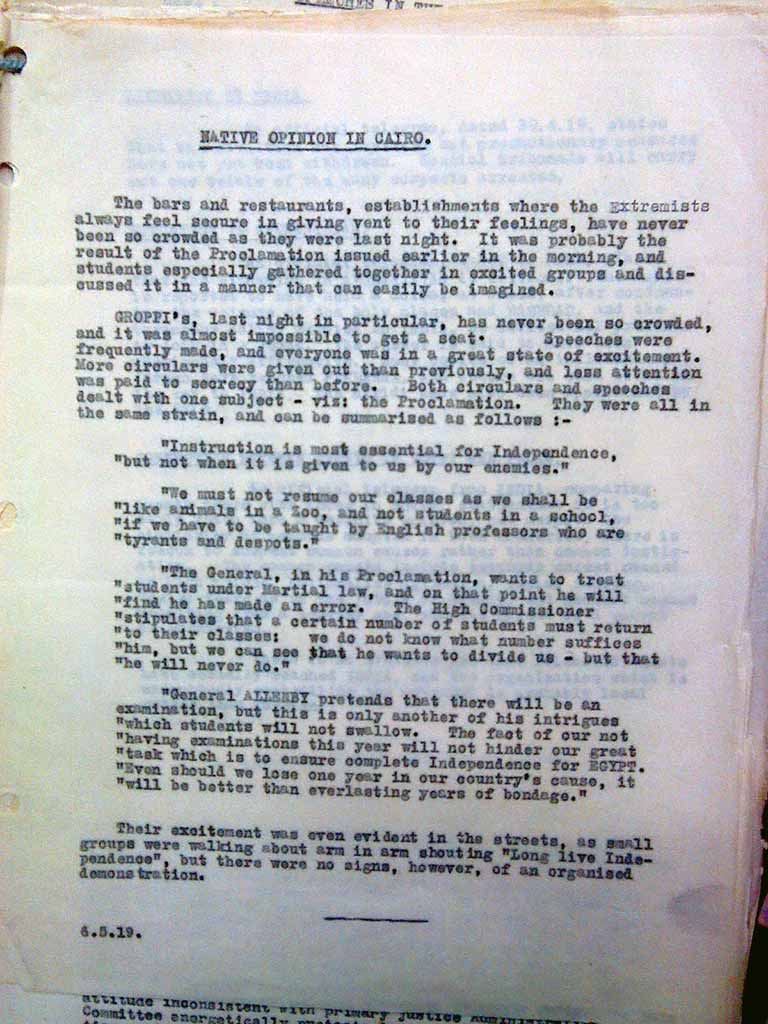

Military Intelligence report, dated 6 May 1919, recording speeches made, circulars distributed, and opinions heard in Groppi, the most famous café in Cairo, regarding a proclamation by General Allenby that striking students should go back to schools and universities (catalogue reference: FO 141/781/6)

I did not have to look for long. The very first document I came across, opening Foreign Office files from Cairo in 1919, was a copy of a daily military intelligence report (Egypt was still under British military rule back then). It had a sub-section titled ‘Native Opinion in Cafés and Bars’. Almost all the hundreds of daily reports from that year had.

They recorded the debates between Egyptian middle-class men, who populated those coffeehouses, and followed closely the political news, as well as the various strikes of workers and civil servants. They recorded how those coffeehouses served as hubs for information and mobilisation.

‘The bars and restaurants, establishments where the extremists always feel secure in giving vent to their feelings, have never been so crowded as they were last night. It was probably the result of the Proclamation issued earlier in the morning, and students especially gathered together in excited groups and discussed it in a manner that can easily be imagined.’ (FO 141/781/6)

Newspapers were avidly read aloud there, pamphlets from the various nationalist parties or the strike committees were regularly distributed there, and slogans or speeches were heard there. Instructions for strikers and demonstrators were also made known in coffeehouses. Even the coffeehouse waiters’ guild went on a protest strike for a week or so in August 1919.

Excited by these findings, I was sure I had exhausted this kind of archival source. But before continuing to check out others, I planned a three-day stop in Durham University’s Palace Green Library, where the Mohamed Ali Foundation had deposited the personal archive of Abbas Hilmi II, the last Khedive of Egypt (r. 1894-1914). I was tipped about this special collection, the Abbas Hilmi II Papers, by my PhD advisor, Professor Heather Sharkey, from the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, in the University of Pennsylvania, but we both assumed that I would not find much there: after all, how would the personal papers of the Khedive help to shed light on coffeehouses?

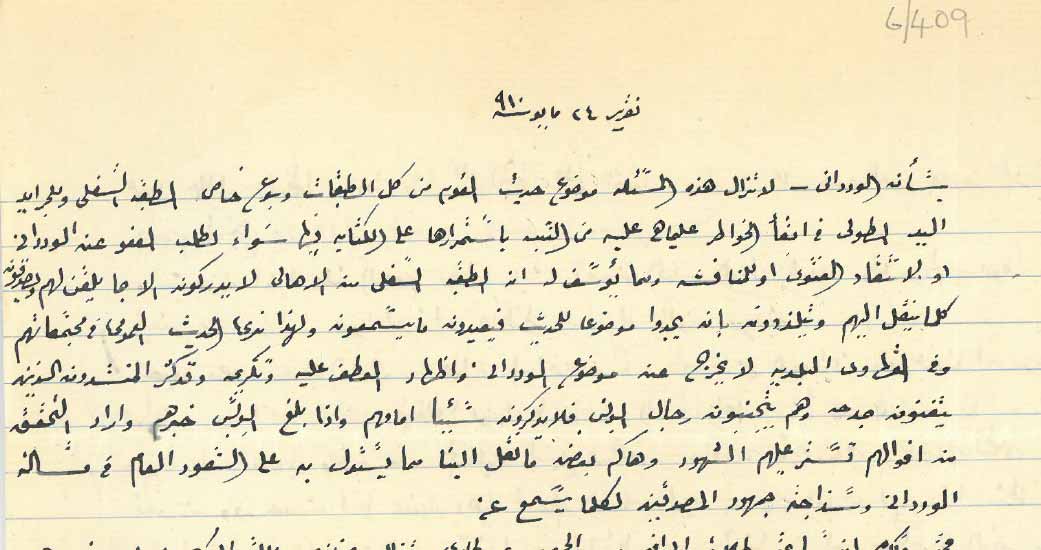

Those three days turned to more than three weeks. Although the term ‘coffeehouses’ does not appear in the catalogue of this vast collection, I did notice files titled ‘Ministry of the Interior’ or ‘Egypt Internal Politics’ with the term ‘reports’ in them. Building on my experience with British intelligence reports, and knowing that Egypt’s Interior Ministry was also responsible for surveillance and policing in those early times, I decided to try my luck. Once again, I hit a jackpot. Those ‘reports’ in this case from 1908-10, were indeed Egyptian intelligence or police reports, in hand-written Arabic. They recorded conversations and opinions heard in coffeehouses frequented by the new middle-class, and even lower classes, which were increasingly involved in nationalist, and anti- government, politics.

‘The al-Wardani case – this issue continues to be the topic of conversation for the people of all classes, especially the lower class… The lower classes know only what is reported to them, and they believe everything that is related to them. They enjoy having a topic for conversation, and they repeat what they hear. For this reason, we see that the general talk during their gatherings in the popular coffeehouses does not go beyond the issue of al-Wardani, display of emotions for him, or revering him… They avoid policemen, and plead ignorance when confronted [about their conversations]…’ (Abbas Hilmi II Papers, HIL 6/409)

Beginning of a report from the Egyptian Ministry of the Interior, dated 24 May 1910. It reports on the talk of ‘the lower classes in their gatherings in the popular coffeehouses’ regarding the trial of al-Wardani, the nationalist assassin of Egyptian Prime Minister, Boutros Ghali (Abbas Hilmi II Papers, HIL 6/409, reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of the Mohamed Ali Foundation and of the University of Durham)

Moreover, the Khedive also employed private agents and informants, who reported to him directly, and spied on what was said and done in coffeehouses. For example, in reports from 1901-2, informant number ‘294’ wrote about men seeking favours in the court; about rumors and conversations on governmental corruption, and political scandals; or on journalists boasting about their anti-Khedive columns.

In short, through my journey in The National Archives and Durham University’s Special Collections, I discovered an unusual source of information for the social and political history of Cairo’s coffeehouses, namely, spy reports. Thus, through the eyes of Egypt’s rulers, be them the Khedive or British High Commissioners, I not only learned about the state’s interests in, fears of, and efforts to control, public opinion, but I could also reconstruct how coffeehouses increasingly became an urban space for popular politics, as they became the hub and the seat of an increasingly politicised Egyptian middle-class.

Connecting Collections is a series of blogs by academic researchers, exploring the connections between archives across the UK and around the world.

where and how can we obtain the research paper of ALON TAM `coffeehouses in cairo` if published. thanks.

Thanks for your comment. It looks as if you should be able to access the research paper here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326675417_Cairo's_Coffeehouses_In_The_Late_Nineteenth-_And_Early_Twentieth-Centuries_An_Urban_And_Socio-Political_History

Kind regards,

Liz.