At the turn of the 20th century there had been no war between any of the six great powers in Europe since 1871. There had been disputes, but no military mobilization by the powers. The balance of power was thought of as a natural leveller: if any one power became too strong then a slight shift in alignment between the others would safely restore the balance. This train of thought was put to the test in July 1914, which ultimately started the timetable to mobilisation.

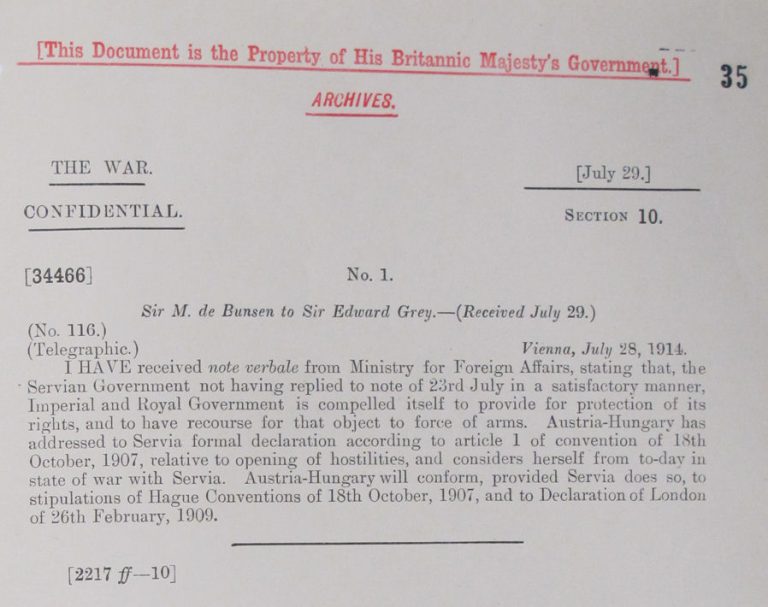

Austrian government considers herself at war with Serbia. Catalogue ref: FO 471/2159 paper 34466

Following the assassination of the Arch Duke Franz Ferdinand, Austria mobilised her forces on 25 July, as they were expecting the Serbian Government to reject their ultimatum. Serbia (formerly known as Servia) mobilised by 27 July, having rejected most of the points in the ultimatum.

Russia had an informal agreement with Serbia, and were not about to lose face by allowing the Austro-Hungarian forces to attack their ally. Russia planned for a partial mobilisation, but after the Balkans War in 1912, they realised that they could not partially mobilise. Russia had no border with Serbia, so any mobilisation would antagonise Germany. This resulted in a full Russian mobilisation (29 July) to protect their border with Germany. Germany responded with their own mobilisation to protect their ally Austria and the borders with both Russia and France.

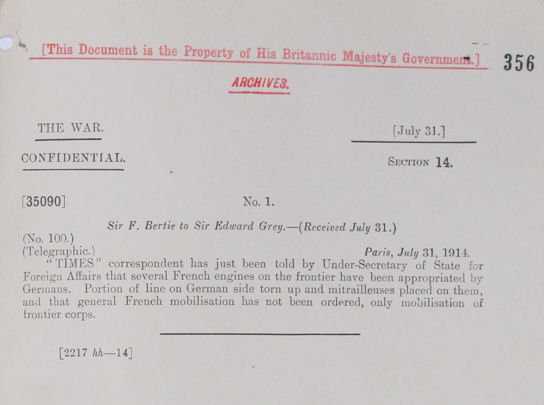

After the Franco Prussian war of 1870-1871, France wanted to see Germany put herself in the wrong. French military plans were adapted accordingly but delayed, so France couldn’t be accused of starting hostilities, again. France desperately wanted to win Britain over to its side, even though Britain and Italy did not really have any direct cause for entry into the conflict.

Russian full mobilisation in response to German and Austrian mobilisation. Catalogue ref: FO 371/2159

Germany mobilised her forces in retaliation to the Russian mobilisation on their border.

This chain reaction saw Holland and Belgium (29 July) mobilising forces on a defensive line. Both countries issued declarations of neutrality, but declared they would defend themselves if invaded. France mobilised her forces (2 August); Germany now had Russian mobilisation on one side, and the French on the other side.

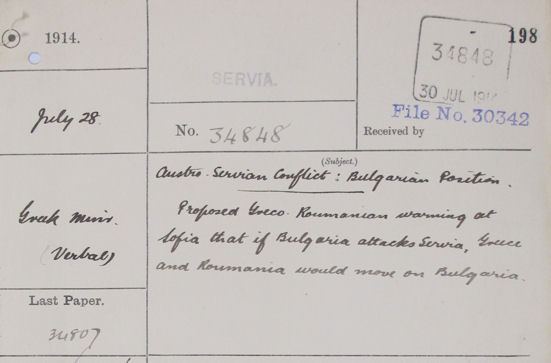

Other European states started to mobilise for a defensive stand. Greece and Romania (formerly known as Roumania) both mobilised (30 July) but declared they would not intervene in the ‘localised conflict’ in Serbia, although they declared if Bulgaria attacked Serbia, Greece and Romania would move on Bulgaria.

Britain and Italy took different stances. Russia and France had requested Britain to side with them, to deter Germany from supporting Austria. Germany wanted Britain’s reassurance they would stay neutral, and try to influence Russia to demobilise. Britain took no sides or action but pushed for a conference between Russia, Serbia and Austria. Their concern was not mobilisation, but military action. Italy, the last of the six European powers, declared their neutrality, and pushed for a peace conference.

Position of Greece Romania and Bulgaria (30 July). Catalogue ref: FO 371/159 paper 34848

Although all the powers relied on alliances for their own security and power, they essentially relied on their own strengths, which took a common form. They all had huge armies mostly composed of Infantry, based on a system of young men having had some intensive military training and becoming liable to call up should the need arise, known as conscription. In this way every country could count on several million men to be on hand and ready for war by the operation known as mobilisation. Britain was the exception; they did not have a large standing army or use conscription to supplement a reserve army.

Europe had generally maintained that ‘certainty was synonymous with security’; and certainty was most obviously seen in the railway timetable. A man could quite confidently state where he would be down to the minute, at any given time even a year ahead, through the railway timetables.

Mobilisation involved every newly discharged man re-joining his unit which would then join a higher Brigade until the armies were complete. Not only would the men be on the move, but also the light and heavy guns, ammunition, horses, fodder, supply wagons, first aid stations, field kitchens; everything would be on the move and movement was by train.

France had for a long time labelled every railway wagon: ‘40 men or eight horses’ and the wagons in other countries were labelled similarly. This entire process of war would be moved by rail to the assumed point of battle; the general staffs would have spent many years perfecting these timetables. It was universally accepted that speed was of the essence; whichever power completed its mobilisation first, would be the first to strike and therefore could even win the war before the other side was ready. The timetables became so very important and so very complicated. By 2 August 1914, all over Europe the international express trains had stopped running, troop trains ran instead.

Mobilisation was a manoeuvre in itself at the end of which the armies must be ready to strike. There was no room for manoeuvres once at the battlefield. There would be no time. Every fully equipped unit had to be ready to move at a given hour on a given day, to get to a given destination by a pre-arranged train, which in its turn must be moved according to a precise and carefully planned railway timetable. No change or alteration was possible during mobilisation. Improvisation was out of the question. When one thinks that in the case of the French, nearly 3 million men and 4,278 trains had to be organised, it was a daunting task which had to be carried out to the letter. One mistake and it all could fail.

French engine appropriated by Germans. French frontier forces mobilised. Catalogue ref: FO 371/159 paper 35090

These elaborate plans had however, never been tried in practice. Only Russia had mobilised before, the other great powers had never mobilised. This would have put too much strain on the railways. Some general staffs trusted the complete efficiency of their own and others’ systems, while others expected there to be frequent errors in their timetables and consequently allowed for this. However, the strategists had one thing in common, they all felt the one plan to stick to was that of ‘no improvisation’ and consequently all became prisoners to their own timetables.

It was the importance of the timing of mobilisation, the orders and troop movements which decades later was to become a passionately fought debate of the causes of the war.

Many theorists believe a major cause for the outbreak of war in 1914 was Germany’s Schlieffen plan. This strategy required rolling through the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxemburg unopposed, driving a strong line of attack west and south of Paris, and capturing the capital, while the main thrust of the invasion encircled the French army in one brilliant move. This plan basically relied on speed and the offensive. However in 1914 both the French and the Russians believed they were strong enough to face the threat of Germany (whereas in the past this would not have been true) and when Germany demanded that France and Russia not mobilise, it was more than they could accept. The powers were trapped by their own defensive mobilisation, each defensive plan appeared to be an attack to somebody else, nobody had time to think and therefore for everyone, the deterrents failed to deter. Once the wheels of war started to turn, they could not be stopped.

[…] Timetable to mobilisation […]