When the NHS was founded in 1948, film was in at the ground floor. Ever since, documentaries, dramas and animations have helped promote, explain and run this great and complex public service. Many, commissioned through the Central Office of Information (COI) by the Ministry of Health and its successors, are officially part of the government archive.

Ever since the 1958 Act provided for films to be designated Public Records, The National Archives has collaborated with specialists at the BFI to preserve and make available the 4,000-odd productions so designated. Meanwhile, The National Archives’ own vaults house the COI’s production files for many of them.

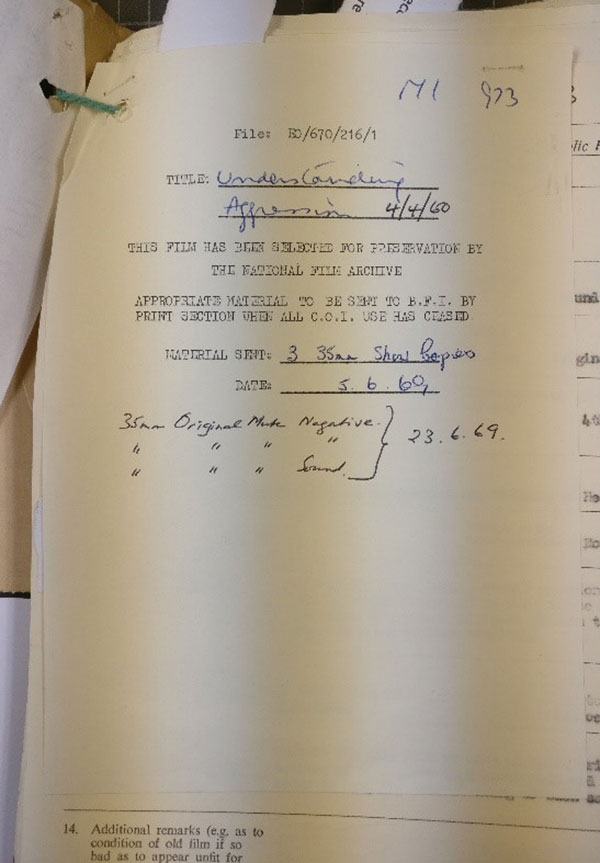

Prints and – crucially – the original negatives of ‘Understanding Aggression’ entered the BFI, via the Public Record Office (now The National Archives), nine years after production. (Presumably after it had stopped being used as an NHS training tool). Catalogue ref: INF 6/2051

So, in connection with NHS70, we’re doing a wee experiment: reciprocal blogging. Over at the BFI’s website, The National Archives’ Christopher Day applies his expertise as a state archivist to films that were, ultimately, applications of government policy. Here, I’m bringing BFI eyes to government records, films and files: two fascinating, contrasting dramas available in the NHS collection on the BFI Player: ‘Life in Her Hands’ (1951) and ‘Understanding Aggression’ (1960).

When you open an archive production file, you never (to paraphrase Forrest Gump) know what you’ll get: a fat folder of revealing correspondence or a solitary dreary contract. These two files fall in the middle: nothing mega-juicy but some worthwhile pickings.

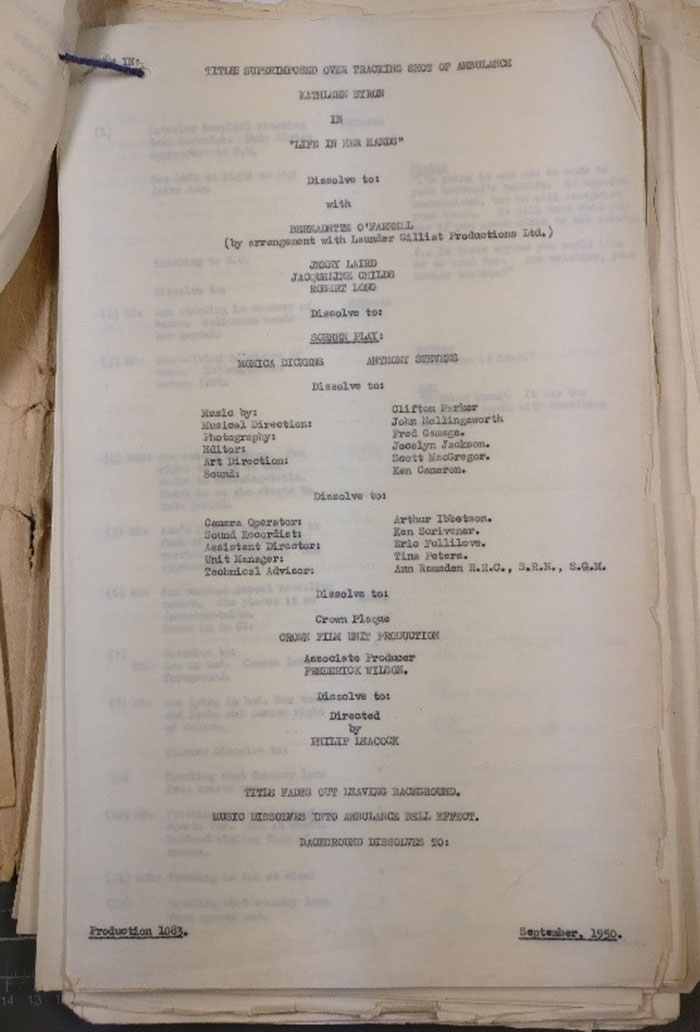

‘Life in Her Hands’ is one of the most ambitious recruitment films ever made – an hour-long drama government-sponsored B-movie! The file reveals that, before the project was committed to the government’s in-house Crown Film Unit, a treatment was prepared by famed documentarian Paul Rotha’s company Films of Fact (which would soon go out of business). It had the prosaic working titles ‘Nursing Services’ and ‘Staff Nurse’. The Irish writer, Frank O’Connor, was flown in to advise the script, which was co-written by well-known novelist Monica Dickens and Anthony Steven, later a prolific TV drama hack. Crucially, a retired senior matron and the editor of the Nursing Times were professional advisors, ensuring appropriate representation of NHS practices and a degree of realism. Crown contracted with United Artists for cinema distribution and the British Board of Film Classification demanded small cuts before granting the finished picture an ‘A’ certificate.

Front page of script for ‘Life in Her Hands’. Catalogue ref: INF 6/1938

The film’s sheer expense is partly what makes it so interesting. Philip Leacock was undoubtedly assigned to direct on account of his successful ‘Out of True’, the previous year’s Ministry of Health drama – these productions proved stepping stones into a feature film and TV career. Here he helmed a full-on short-feature melodrama, a ‘women’s picture’ twist on the wartime propaganda ‘story documentary’ for which Crown was famed. Involving, if not always subtle, it serves a genuinely rather subtle recruitment message. Rookie nurse Byron reaches her happy ending via trials and crises. Nursing’s not for sissies, but if you think you’re tough enough you’ll reap rich emotional rewards.

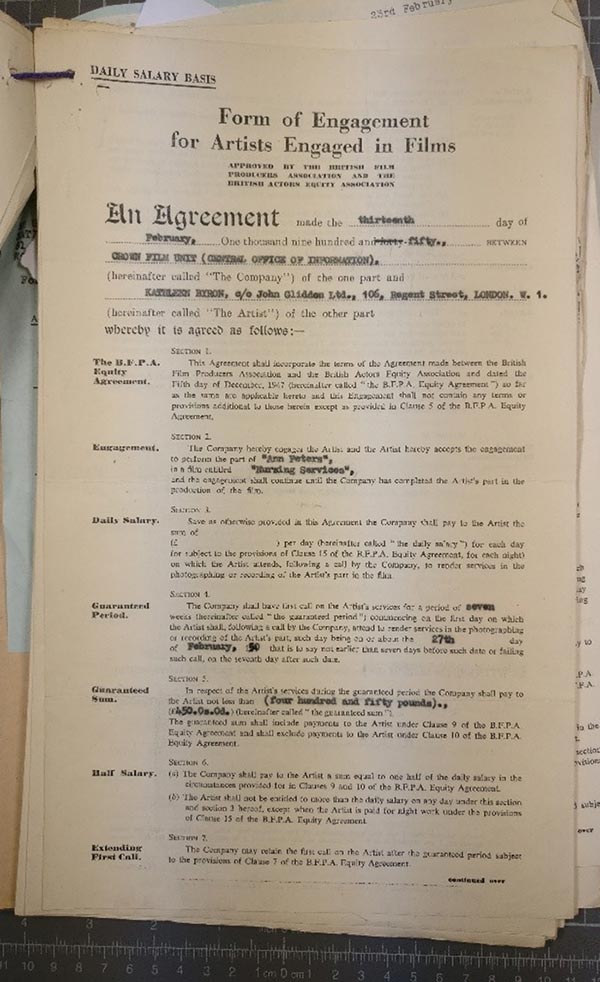

Kathleen Byron’s contract for starring in ‘Life in Her Hands’. Catalogue ref: INF 6/1938

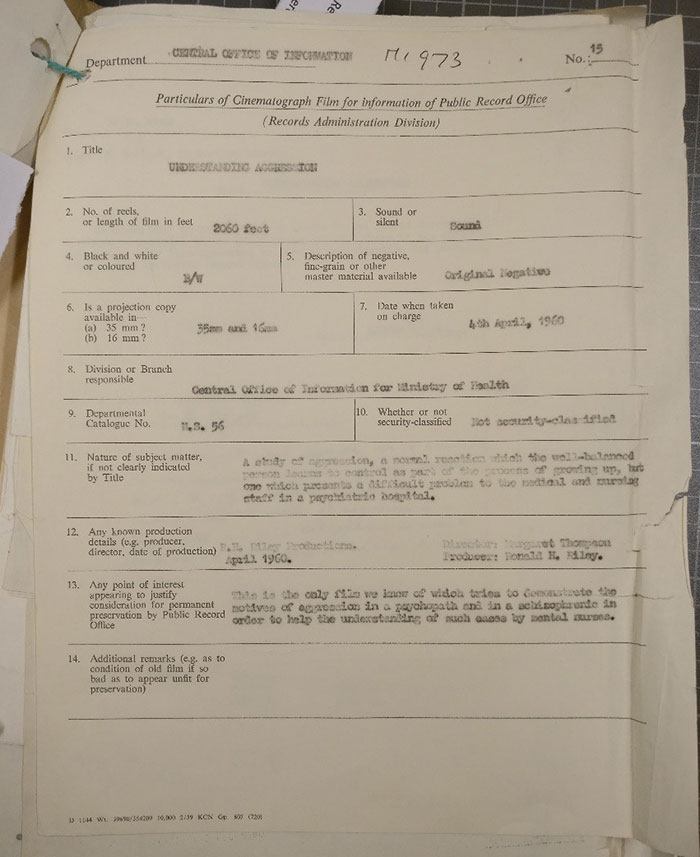

A year later, Crown was closed. ‘Understanding Aggression’, an internal NHS film used to train psychiatric nurses, was produced by an external contractor, the prolific RHR Productions.

It was directed by a woman, Margaret Thomson. New Zealander Thomson made numerous films from the 1930s to the 1970s: one of several female directors in the short films industry. The COI knew her from earlier commissions, including two mental health projects. The National Archives file shows that they paid her £125 to investigate and write a treatment for this film, then another £125 to write the script, before bringing RHR in to produce (ultimately paying them £6,357, which would have included Thomson’s director fee). COI practice was to every film assign a ‘Controlling Officer’: in this case, the file reveals, it was Derek Mayne – himself a former film director – liaising between the Ministry of Health and RHR.

COI Summary of ‘Understanding Aggression’ for the Public Record Office (now The National Archives). Catalogue ref: INF 6/2051

NHS films were often shot on location in hospitals, but typically don’t identify them (a distraction in films for nationwide distribution). This one, it seems, was shot at Horton Hospital (presumably Horton General, Banbury), plus a location described as the Old Mill House, Ewell. The file also indicates extensive use of COI stock footage, most obviously in the opening scene where footage of aggression between children is shown being projected. (This is taken from Thomson’s own early COI work, 1946 childhood observation films for the Ministry of Education). It is also used less obviously in the cricket scene, where some general views derive from Humphrey Jennings’ 1950 film ‘Family Portrait’.

The working titles were ‘Management of Violently Disturbed Patients’ then ‘Handling [of] Aggression’, according to the file, which documents a gradual tightening of Thomson’s ideas through different phases of script, scene breakdown and shooting schedule.

Only nine years on, Thomson’s style feels strikingly more modern than Leacock’s, even if his touch is a little more consistent. Her film’s a tad gauche (notably, one of the aggressive patients is a rather am-dram interpretation of an Angry Young Man). However, it still impresses as humane staff education. It is, in places imaginative and stylish (the undoubted visual highlight being the sequence visualising a schizophrenic patient’s delusions of being followed around by a giant eye). The inclusion of black and Irish nurses appropriately mirrors its target demographic; they’re placed within a collaborative, discursive environment where colleagues learn from each other, and base clinical solutions – in part – on empathy with patients.

Between the COI’s working titles and Thomson’s final one there’s a telling shift: from ‘management’ and ‘handling’ to ‘understanding’.