This year, as part of our First World War 100 commemorations, we’ve been focusing on the Home Front – the experiences of the civilian population living in Britain’s towns, cities and villages, whose lives were greatly affected by the war.

We have one of the richest collections of First World War records in the world. The chief aim of our First World War 100 commemorations is to publicise and offer new insights into our records to encourage everybody to engage with them – whether that is through researching an ancestor’s military career, or studying the conditions of female workers in munitions factories.

In order to do this, we have digitised records, catalogued thousands of individuals’ records and hosted events including webinars and a contemporary art exhibition. And we’ve also built a fictional town: Great Wharton.

Founding Great Wharton

Katie and I are both part of The National Archives’ Modern Domestic Records team, who took a key role in exploring the records we hold on the Home Front.

However, this was not an easy task. ‘The Home Front’ covers an incredibly wide range of topics and the records we would use would not be found in a specific part of our collection – they are scattered throughout thousands of files created by dozens of government departments.

As part of our daily work as records specialists we come across records which offer an insight to domestic life in the First World War, sometimes relating to well-known things like conscientious objection, sometimes about more obscure aspects, like a government ban on selling fresh bread.

We wanted to create a resource which would allow people to engage with these in an absorbing way, showing the stories that someone could find if they explored our records, in a different way to our ‘business-as-usual’ method of making records accessible – catalogues and research guides, which can be daunting for first time users.

Our colleagues in the web team suggested creating a stylised, fictional town to host the stories, as opposed to a map. This was perfect – it gave us a small, fictional virtual corner of Britain from which we could explore the entire Home Front. We decided to call it Great Wharton – a pun apparently so subtle it’s become a private joke among us.

Exploring records

Once we had a concept, we needed to decide the kind of stories we’d like to tell using it, and find records to shed light on life on the Home Front. As a team, we collated records we’d already found and noted whether they were interesting or not. This involved looking at documents thoroughly and seeing if they lived up to their intriguing descriptions in the catalogue.

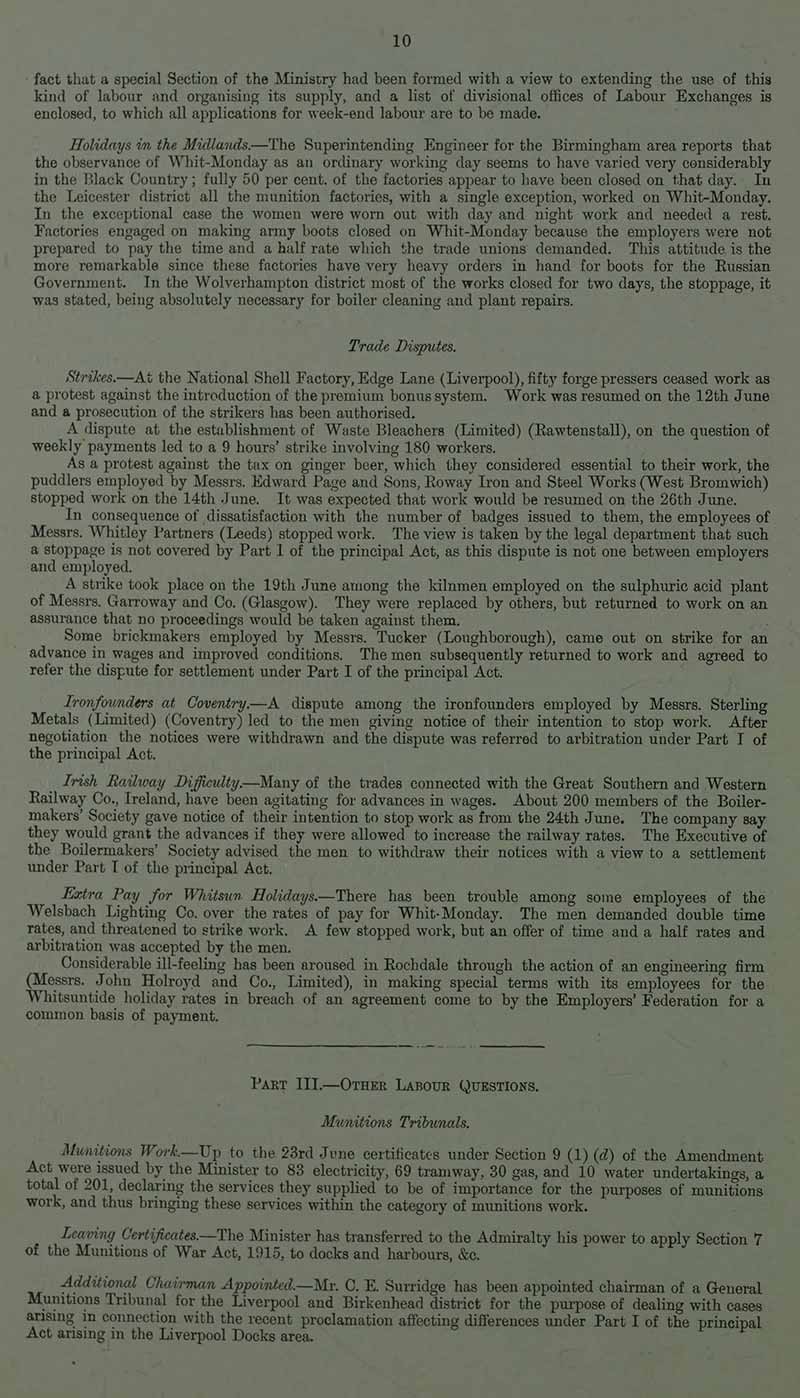

A digest of reports on trade disputes that took place in June 1916, taken from the ‘Labour’ volume of a collection of bound weekly classified circulated among high ranking members of the Ministry of Munitions (catalogue reference: MUN 2/27)

Government records rarely offer a comprehensive picture, or overview of a topic. They are working documents and often deal with very specific areas. This can be fascinating, like a Ministry of Munitions document which details a strike by steelworkers in protest of a tax on ginger beer that ‘they considered essential to their work’.

It can also be dull. A Ministry of Transport document relating to the hire of tug boats in dockyards sounds like it might offer insight into conditions in dockyards or shipping arrangements; in fact, the file only contains an unfinished draft response about hiring tug boats.

To focus our search we decided to search for record stories that fell into ten broad categories, including children and young people, enemy action and crime and unrest. We then set about searching Discovery, our catalogue, for documents that would be a worthwhile addition to Great Wharton.

One of the topics that Katie wanted to research was the experience of Boy Scouts during the First World War. She began by doing an advanced search in Discovery looking for documents from 1914-1919 using the keyword ‘scouts’. This search came up with 3,734 results – far too many for Katie to browse through! She decided to refine her results by collection, and chose to focus upon records with the ED (Board of Education), NATS (Department of National Service), AVIA (Air Ministry), CAB (the Cabinet) and HO (Home Office) letter codes. This helped enormously and refined the results to a manageable 23. Out of these, Katie was able to find HO 45/10734/258763, the record she used to write ‘Scouts called to action‘.

If you would like to research the Home Front during the First World War we recommend having a look at our research guides, which give you hints and tips on the record series that might be most relevant and how to search. You can also look at our Discovery Help page.

Telling stories

Locating the records was possibly the easiest part of our work. Becoming disconcertingly passionate about the records is an occupational hazard of working at The National Archives, and as record specialists we are making discoveries in our collections everyday.

Telling stories was more of a challenge – how much background information were we to include? As mentioned, government records are usually light on wider context: they are policy files relating to specific issues and would have rightly assumed that their intended readers had an understanding of a topic.

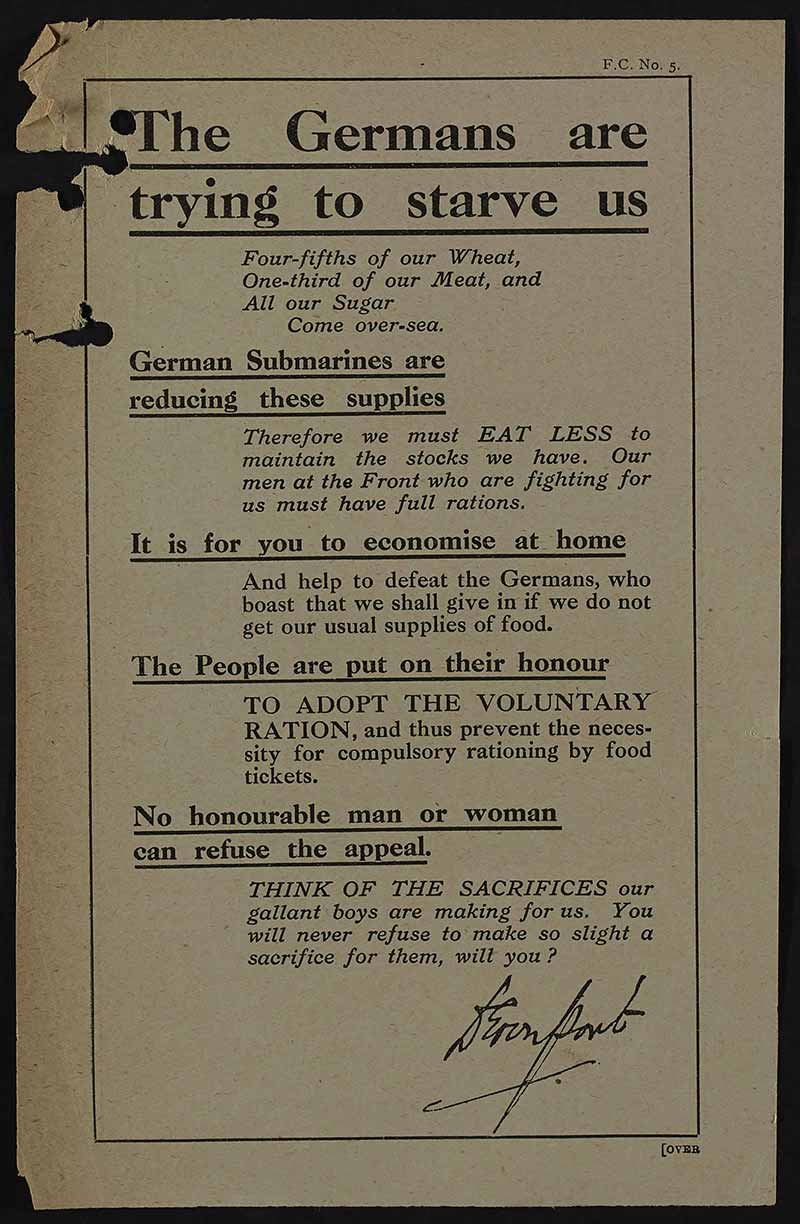

This meant that we needed to add historical content needed to make the stories of these records engaging. For instance – a leaflet encouraging people to adopt voluntary food rations is quite interesting in itself. It’s obviously historical, visually arresting and appeals to our collective enjoyment of vintage propaganda.

Leaflet produced by the Ministry of Food and National War Savings Committee in order to persuade British civilians to adopt voluntary food rations due to wartime shortages, 1916-1917 (catalogue reference: NSC 7/37)

However, it becomes more interesting if you know its context: voluntary rationing was promoted because the Cabinet were worried that Britain’s allies would view the introduction of compulsory rationing as a victory for the German Navy; and the Minister of Food was concerned that the country would run out of food in winter 1917. These contextual additions bring the record to life – making it more than just an interesting historical document. Its interpretation allows it to give an insight about daily life on the Home Front.

This is what we have attempted to do with Great Wharton, draw out fascinating oddities from our vast First World War collections, shining a light on some of the Home Front’s untold stories, and using these to think about the broader themes that affected civilians in the First World War.

Great Wharton is now open to ‘visitors’, but its story isn’t over yet. The design allows the town to be updated with new stories as our centenary commemorations progress.

Visit Great Wharton: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/first-world-war/home-front-stories

On food rationing I would say that it was not just the issue of German submarines , but the fact that most men were fighting overseas led to problems getting in the harvest didn’t help although some people (like the Perrin family of Sudbury Court Farm in the Harrow/Wembley area) had been exempted from military service because they provided hay for the horses. I think it would be fair to say on the Home Front that ‘health and safety’ went out of the window during the First World War, women working at munition factories without adequate safety and the Silvertown Explosion in East London in January 1917 being but two examples. I would say have a look at Treasury files (T 1 series) and the Official Histories written after the war for an overview and Government files rarely give the whole story because that is not what they were created for, but for a particular moment in time.

So proud to be a BRITISH.