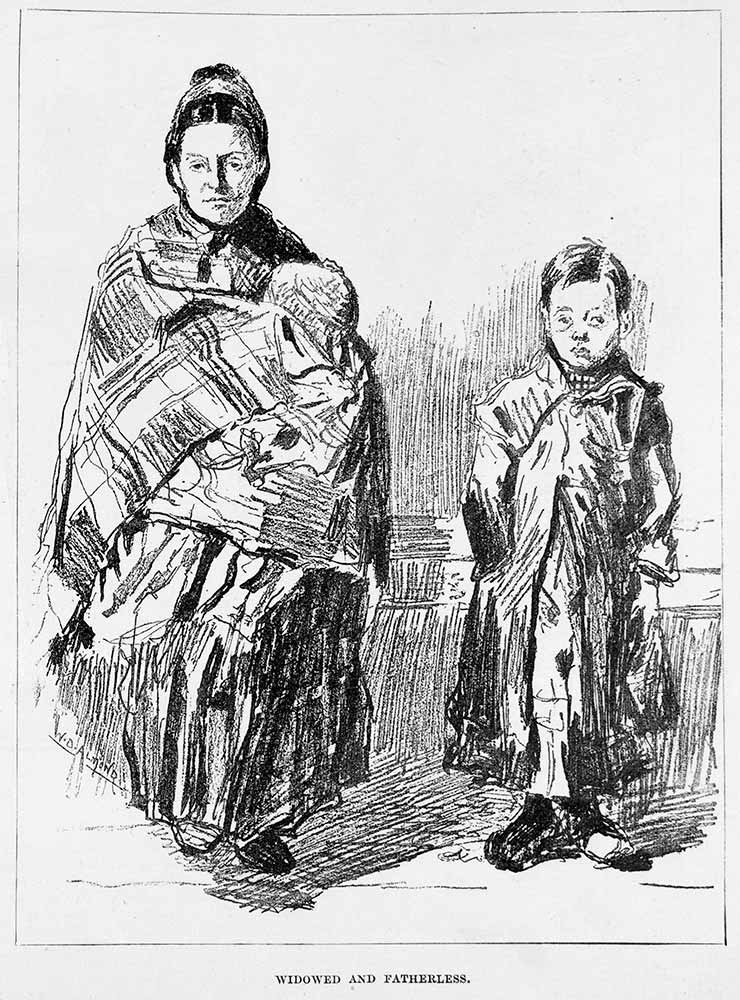

Widowed and Fatherless, Illustrated London News (catalogue reference: ZPER 34/93 p351)

March is Women’s History Month, which aims to highlight the lives and achievements of women throughout history. I am a post-graduate researcher working in collaboration with The National Archives and the University of Leicester, and I am particularly interested in telling the stories of women and widows.

As a researcher, I have discovered that when I delve into records for the lives of women I also come across the stories of the lost, the marginalised and the hidden. This type of research reminds us that we must continually strive to go beyond the boundaries of what we have considered worthy of research and discover more histories for the next generation. Within the records held at The National Archives there are countless names, lives and stories still to be explored.

My research looks at the warfare that dominated England during the mid-17th century period. During times of war lives are lost, livelihoods destroyed and communities changed. The same was true of the English Civil Wars and the Anglo-Dutch Wars. Women lost husbands and sons; children lost fathers and homes. I have read many petitions presented by women who, as a result of the wars, were made widows and left with fatherless children. The documents can be heartbreaking to read and show how women suffered and survived during this period.

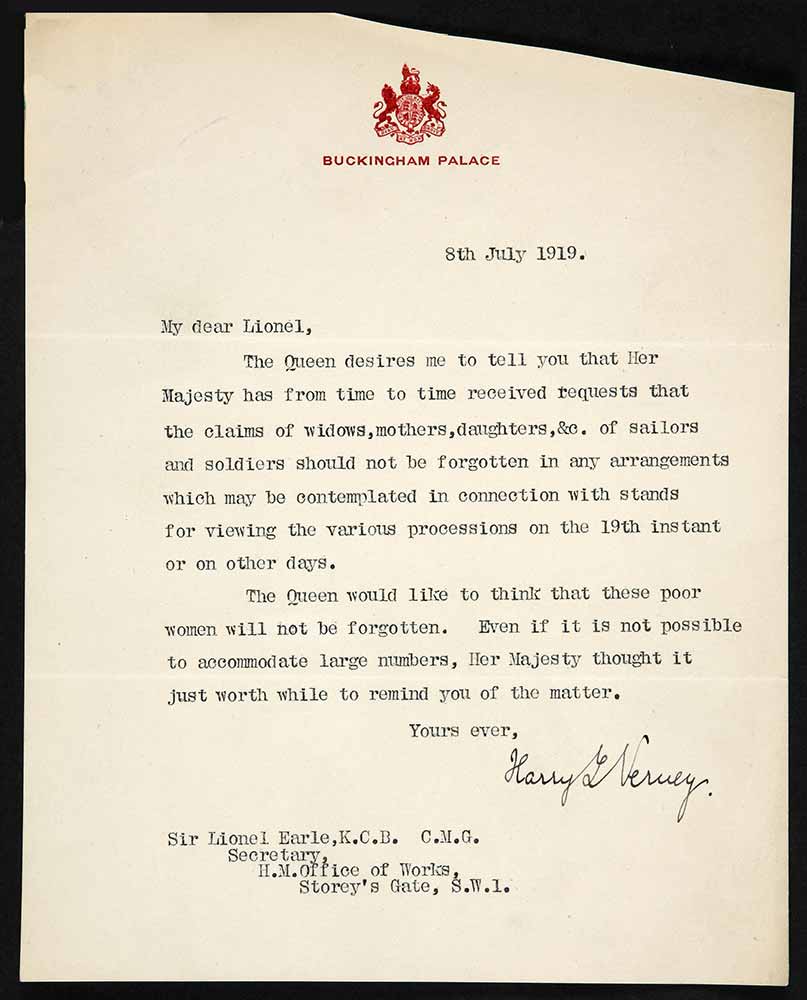

This isn’t just an issue in the 17th century, of course. Warfare throughout history has left victims on the battlefield as well as at home. The image below records the Queen’s concern that widows be provided for following the end of the First World War.

Queen’s note that claims of widows should not be forgotten (catalogue reference: WORK 21/74)

It may be surprising to some, but as far back as the early modern period the government did acknowledge some responsibility for the dependents that war had created. During the Civil Wars of 1642-1651 Parliament allowed the widows of those who had fought for them to claim a pension. In the 1650s they also allowed a one-off grant of up to ten pounds for the widows of those who had died at sea in the Anglo-Dutch wars.

War widows sent in their petitions to Parliament for money. For many of these women, all that we know about them are these words, written at a time of desperation and need.

Lucy Collier’s husband was a quartermaster who died fighting for Parliament against the Dutch. Following his death, she presented her petition to the Admiralty Commission asking for some financial help. In her petition she described her plight:

‘your poor petitioner and her poor young children are left in sad sorrow and great affliction and ready to be tumbled in goale for debt not having bread to eate nor wherewithall to obteine the same to keepe her & fatherlesse babes from perishing’ [ref]1.Petition of Lucy Collier, 1653 (catalogue reference: SP 18/64 f. 27r)[/ref]

Sadly, the words ‘Nothing can be done’ are written at the bottom of her petition in the hand of an official. We can presume that she received no money. Not all widows were granted the relief that Parliament had promised.

Mary Dalby’s husband had fought on the wrong side (according to Parliament!) during the Civil Wars. He had been aboard one of Prince Rupert’s ships fighting for the King. In punishment, her lands had been confiscated and she was withheld from receiving any kind of welfare from the state. Left alone with three children, she sent a petition asking for some relief. She wrote:

‘your petitioner and her three small Children are left in greate distresse, wanting both food to eate and Clothes to putt on’ [ref]2. Petition of Mary Dalby, 28 May 1646 (catalogue reference: SP 23/79 p. 615)[/ref]

In Mary’s case Parliament appears to have relented and allowed her to receive the profits from her (very small) land holding again.

The petitions of Lucy and Mary are a stark reminder of the cost of warfare in this period and throughout history. These records sit alongside many others which illuminate the experience of women and children who were placed in an even more vulnerable situation by the losses of war. It is also worth remembering that these petitions are a testimony of their tactics for survival.

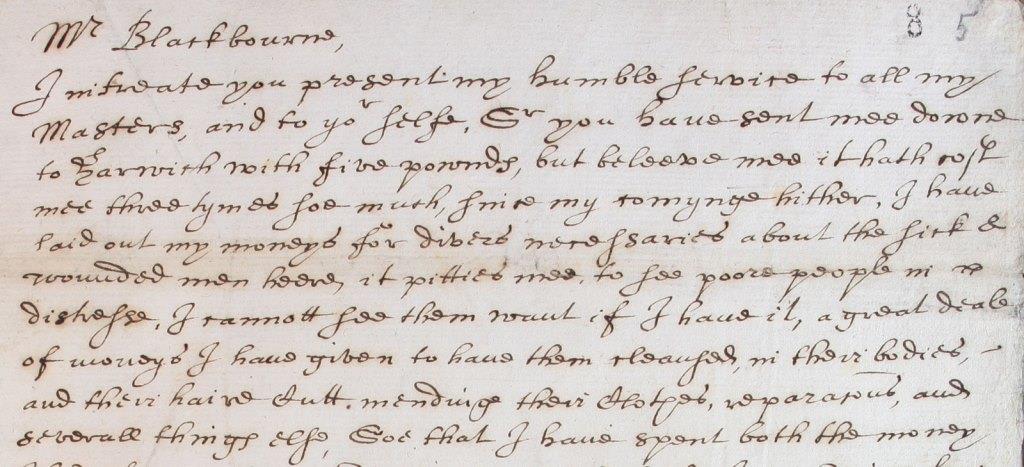

A final example serves to demonstrate one of the many ways in which widows survived the harsh realities of the period. Elizabeth Alkin’s husband had been hung as a spy by the Royalists during the Civil War. After his death Elizabeth continued to supply intelligence about the Royalists to Parliament and she gained the nickname ‘Parliament Joan’. She also worked as a nurse throughout the wars and sought financial remuneration from Parliament for both of these activities. The document below is a letter from Elizabeth to the secretary of the Admiralty Commission. In it she writes:

‘since my comynge hither [to Harwich, Essex], I have laid out my moneys for divers necessaries about the sicke & wounded men heere, it pitties mee, to see poore people in distresse, I cannott see them want if I have it’ [ref]3. Letter from Elizabeth Alkin to the Admiralty Commission, July 1655 (catalogue reference: SP 18/38 f. 9r)[/ref]

Letter from Elizabeth Alkin to the Admiralty Commission (catalogue reference: SP 18/38 f. 9r)

Elizabeth worked with compassion and tenacity in order to secure her survival through this period.

When I read the stories of these women I am continually reminded that there is still much more to be discovered about the ways that people lived and lost through the warfare of the 17th century. By putting a spotlight on the widowed and the fatherless, the marginalised and the hidden, I hope that my work goes some way to ensure that our understanding of the past is rich with the stories and lives of all people.

I will be speaking more about war widows of the Anglo-Dutch Wars as part of The National Maritime Museum’s Women Making Waves public event on Sunday 20 March.

Related reading

Women and the English Civil Wars – education resource

[…] 0 […]

Fabulous and so interesting. How lucky we are in comparison.