The destruction of antiquities and ancient monuments has, sadly, been making the headlines rather frequently. Although there probably are more appalling issues in the world, the loss of history and heritage is heart-breaking. And it isn’t new. Ancient buildings and artefacts which had survived thousands of years have often found an unseemly demise in times of war, especially in the Middle East, even though measures have been taken regularly. Contrary to the legend, however, the Great Sphinx of Giza did not lose its nose to one of Napoleon’s cannonballs!

During the First World War, when many an army was marching through the Middle East, Djemal Pasha, in command of the 4th Ottoman Army, tasked German archaeologist Theodor Wiegand with the setting up of a special monument protection unit, the Deutsch-Türkisches Denkmalschutzkommando. Created in November 1916 on the model of a project being carried out in Belgium and France, this unit was responsible for the preservation of the ancient monuments scattered on the path of the 4th Army, notably in Syria, Jordan and Palestine. Wiegand later wrote that Djemal Pasha had hoped to raise awareness of the glorious past of these regions, but it’s likely that the German archaeologist also performed an intelligence-related role and took advantage of his position to make notes about monuments which could be excavated after the war.

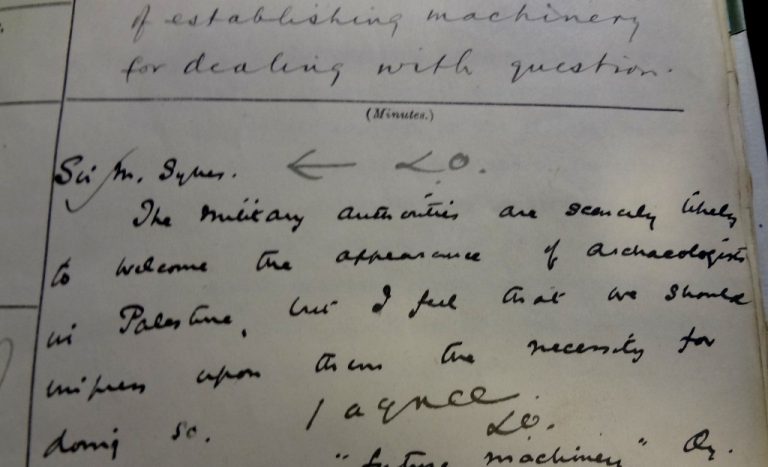

Archaeological matters were also on the mind of the Allied Powers, and not only because a lot of archaeologists were employed by the Intelligence Service. At the beginning of 1918, the Palestine Exploration Fund sent the British Academy a memo relating to ‘certain important questions of historical and archaeological interest arising out of the presence of a British force in South Palestine’, and requested that ‘competent archaeologists’ be attached to the army in the region. This was duly passed on to the Foreign Office who commented: ‘the military authorities are scarcely likely to welcome the appearance of archaeologists in Palestine.’

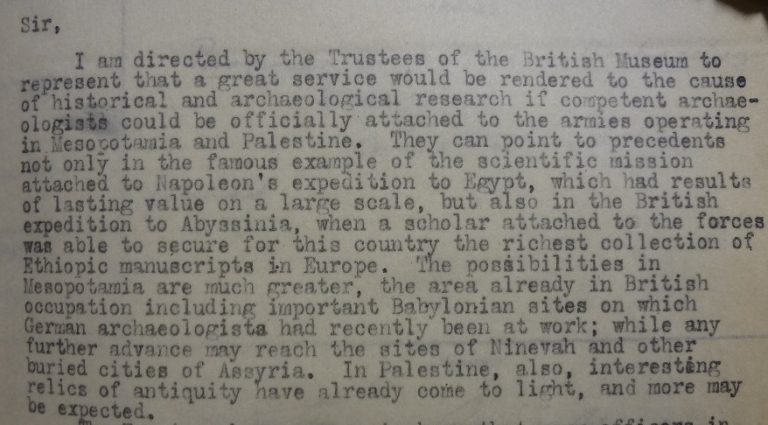

‘The military authorities are scarcely likely to welcome the appearance of archaeologists’ (catalogue reference: FO 371/3398)

The President of the British Academy and Director of the British Museum, Sir Frederick Kenyon, also wrote to the Foreign Office at the end of the year, arguing that ‘a great service would be rendered to the cause of historical and archaeological research if competent archaeologists could be officially attached to the armies operating in Mesopotamia and Palestine.’

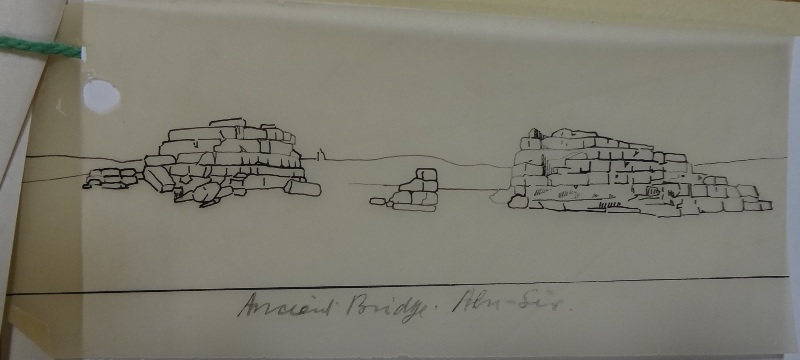

Similarly, during the Second World War, archaeological matters were always in the background – for more worrying reasons. In 1943, Alan Rowe, the Egyptian Antiquities Service’s Inspector of the Prohibited Military Area, Western Desert, and Conservator of the Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria, drew attention to ‘the unsatisfactory attitude of the military authorities in damage caused to antiquities and sites by British troops’. In the summer of 1943, for instance, it was reported that ‘men of the camel corps of the Egyptian Frontiers Administration stationed at Abusir [had] been using the inside of the temple as a lavatory’! Rowe insisted that ‘one particular place which should be guarded is the ancient bridge [at Abusir] (…). This is the only monument of its kind in Egypt.’

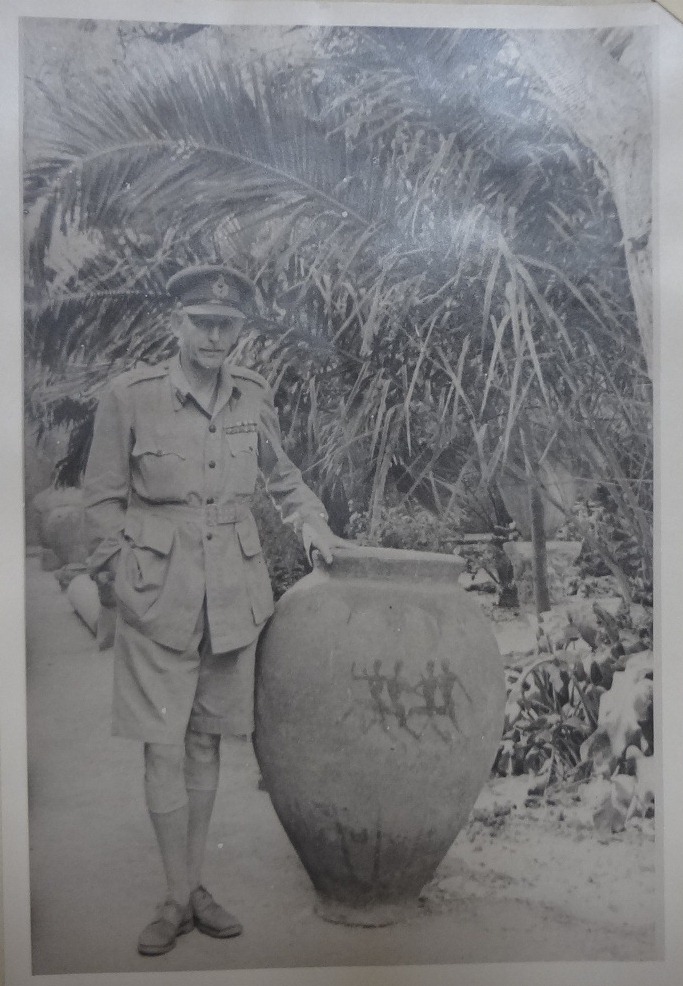

In Cyrenaica (eastern Libya), occupied by the Allies who had evicted the Italians in late 1942, the situation was so worrying that Rowe was sent on a mission, in May and August 1943, to report ‘what, if any, damage [had] been done in the course of the war’, to what extent ‘that damage must be attributed to British troops’ and ‘what steps ought to be taken (…) concerning the preservation of antiquities.’ He toured the major sites and, after the slanderous accusations published by the Italians regarding the attitude of British troops in Libya, the conclusion of his report was rather reassuring: ‘practically no wilful damage at all has been done by the soldiers of the [British and Imperial] armies to the remains of Cyrenaica. Therefore the honour of our armies still stands high in this as in all other respects.’ Some soldiers had scratched their names on the walls of an ancient basilica, but that was a lesser evil. The report also noted the exemplary attitude of some British officers such as Major General Collier, who removed antiquities to a nearby fort for conservation purposes.

Meanwhile, in Tripolitania (north-western Libya), the situation was somewhat less positive: ‘a few cases of gross vandalism by our troops’ were reported, and a report on antiquities was described by the Foreign Office as ‘depressing reading’.

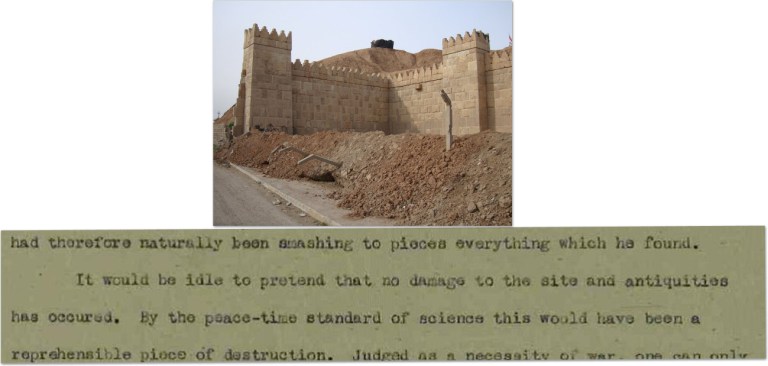

Similarly, in Mesopotamia, the Director General of Antiquities, Naji al Asil, sent British Museum Assyriologist Cyril John Gadd a report on ‘British Army Defence works at Kuyunjik’ explaining that grave damage had been inflicted to the mound of Kuyunjik (the ruins of ancient Assyrian capital Nineveh, on the Eastern bank of the Tigris, near Mosul in northern Iraq) by an unscrupulous contractor paid per cubic metre for broken stone – he had smashed everything to pieces. The technical adviser commented: ‘it would be idle to pretend that no damage to the site and antiquities has occurred’.

Nineveh, Shamash Gate, ‘British Army Defence-works at Kuyunjik’, 19/05/42 (catalogue reference: T 209/10). Image courtesy of Juliette Desplat

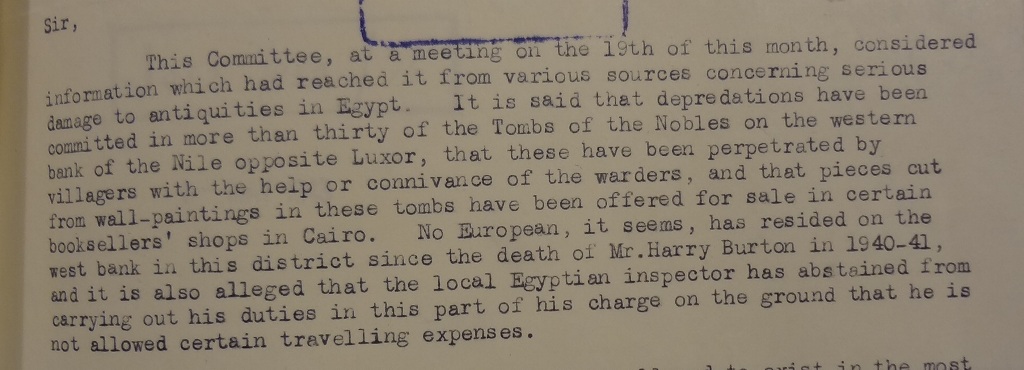

Collateral or wilful damage due to proximity of military targets and/or to the ignorance of troops isn’t the only danger faced by antiquities and ancient monuments during a conflict. Looting and destruction of museums and sites also are a popular sport and a major issue. In 1941, for instance, all the gold objects of the Psusennes Treasure, which had been discovered in Tanis, in the Nile Delta, were stolen from the Cairo Museum. They were all recovered in about eight weeks, and the blame was put on the very low number of guards. Similarly, the increased vandalism in the Theban Necropolis, in the south of the country, where tombs were opened and reliefs cut off, made the absence of Inspectors all the more conspicuous.

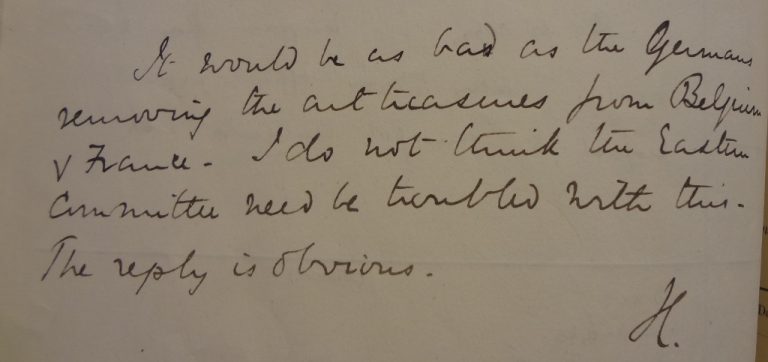

Western Museums also tended to take advantage of the situation to build up their collections. When, in 1917, 96 cases of artefacts left behind by German excavators Sarre and Herzfeld were found at Samara, on the Euphrates, it was suggested that their content should be shipped to England and that the Victoria and Albert Museum would be a perfect recipient. The Foreign Office commented: ‘it would be as bad as the Germans removing the art treasures from Belgium and France.’

Foreign Office reaction to the suggested shipping of antiquities from Mesopotamia to the UK (catalogue reference: FO 371/3410)

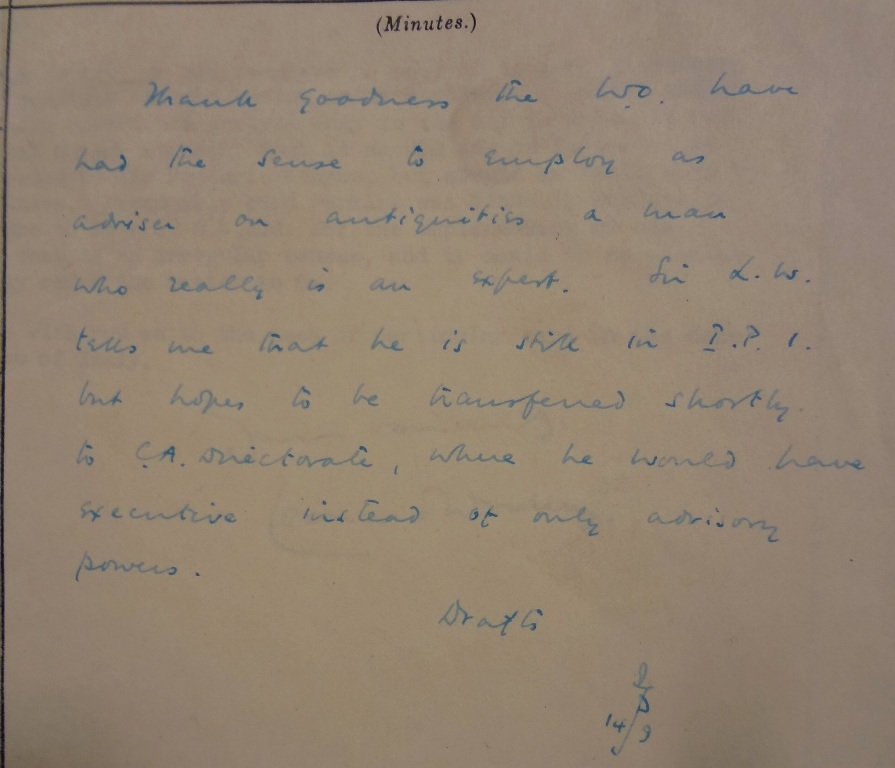

It wasn’t all that bad, though. A couple of months after the occupation of Baghdad, in 1917, General Maude issued a proclamation to regulate the preservation of archaeological sites and the antiquities trade and promised high penalties to anyone desecrating an ancient monument. During the Second World War, Leonard Woolley, who had worked with T. E. Lawrence during the First World War, was appointed as archaeological adviser to the War Office. Even though he was sometimes described as having an interest in buildings which did ‘not extend much beyond 500 B. C.’, having him in position showed that the War Office did take the protection of antiquities and ancient sites into account. Although operational consideration obviously remained conclusive, the importance of historical heritage was clearly asserted.

In 1954, the United Nations’ Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict , which the UK is planning to finally ratify, prohibited the use of monuments and sites for military purposes and reasserted the vital need for preservation and protection. A convention, sadly, doesn’t seem to be enough to safeguard the archaeological sites of Syria and Iraq. Among many other devastating news, bulldozers have made their destructive way through the Assyrian city of Nimrud, Palmyra, in Syria, has been shelled, and the Mosul Museum prized possessions have been smashed into pieces. Some have been calling for the creation of a UN force to protect monuments; others argue that preserving (admittedly priceless) human lives takes precedence.

As Herbert Fairman wrote to his fellow Egyptologist Alan Gardiner in December 1941, it is ‘a state of affairs that fills me with grave disquiet and distress.’