‘What is in that word honour? Air. A trim reckoning! Who hath it? He that died o’ Wednesday. Doth he feel it? No. Doth he hear it? No. Is it insensible then? Yea to the dead…'[ref]1. Henry IV Part I, Act V, Scene i lines 133-138[/ref]

This speech from Henry IV Part 1 uttered by Shakespeare’s much loved character Falstaff should hopefully amuse even the most novice of Shakespeare lovers. As a pillar of self-interest with cowardly tendencies and no regard for honour, Falstaff’s antihero qualities have been enjoyed by audiences past and present. It seems that no act of ignominy or debasement fazes him!

Falstaff first appears as a character in Henry VI part 1, one of Shakespeare’s earliest plays. His creation was in fact based on the real knight, Sir John Fastolf. Yet the Falstaff of Shakespeare’s plays was a character embellished and developed in his own right for the purpose of entertaining audiences. He bore little resemblance to what we understand of the real soldier.

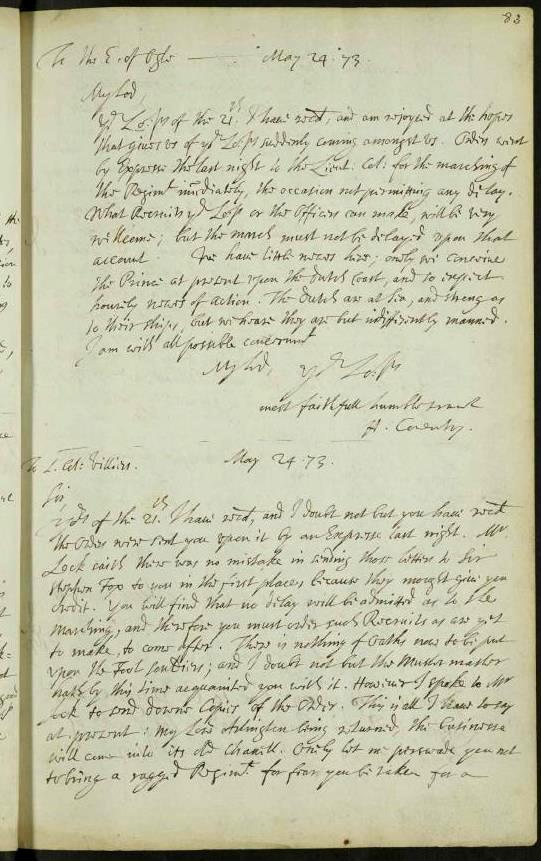

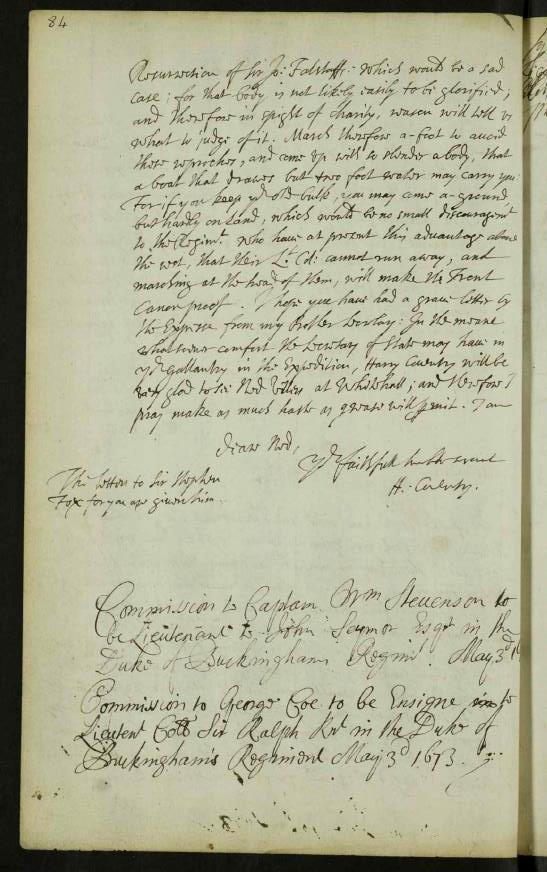

There are few cases in history where a soldier’s reputation has been so badly tarnished through chapter and verse. We observe this in a letter written nearly 60 years after Shakespeare’s death, held within the State Paper records, from the Secretary of the Northern Department Henry Coventry to a Lieutenant Colonel Villiers. In the letter he begs Lieutenant-Colonel Villiers not to bring a ragged regiment of recruits to muster in preparation for service in the third Anglo-Dutch war ‘lest you be taken for a resurrection of Sir John Falstaff’s which would be a sad case…’

- Letter from Secretary Coventry to Lieut.-Colonel Villiers dated 24 May 1673 (catalogue reference: SP 44/29 pp.83-84)

- Letter from Secretary Coventry to Lieut.-Colonel Villiers dated 24 May 1673 (catalogue reference: SP 44/29 pp.83-84)

This obvious slight does not however do justice to the real Fastolf, a reputable 15th century soldier who forged an impressive military career serving three English kings: Henry IV, V and VI.

Records at the National Archives bear testimony to his distinguished military career in Ireland and France, which challenges the image of Shakespeare’s buffoon. We shall look at some of these below.

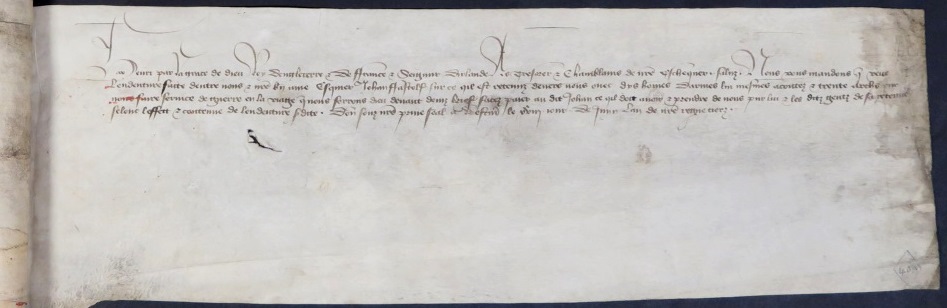

The document below is a warrant sent to the Exchequer ordering payment be made to John Fastolf and 10 men at arms and 30 archers for wages for service with Henry V, dated 18 June 1415. Fastolf did not fight at the battle of Agincourt, having been invalided home from Harfleur, along with many of his comrades, after the town capitulated.

Warrant for issue of payment of wages of war for John Fastolf and 10 men at arms and 30 archers (catalogue reference: E 404/31/405)

Nevertheless in January 1416 he was not only knighted for noteworthy service in the field but was also among the first soldiers to acquire lands in newly conquered territories in France. Fastolf was granted the modest manor and lordship of Frileuse.

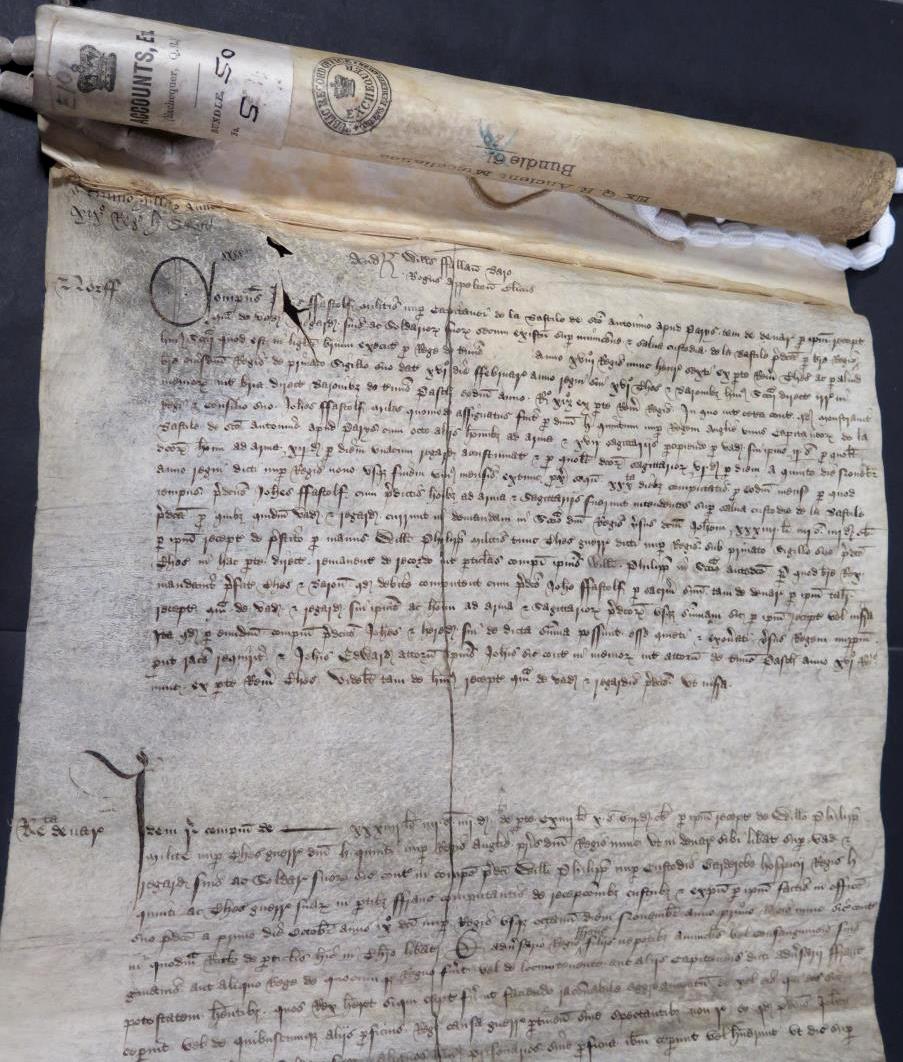

After this, his military career and reputation rose alongside English fortunes in France. In 1421 he was entrusted with commanding the garrison of the famous Bastille St Antoine in Paris, where he gave a good account of himself in protecting the Bastille during an uprising in the capital.

Account of Sir John Fastolf, Captain of the Bastille of St. Antoine, Paris (catalogue reference: E 101/50/5)

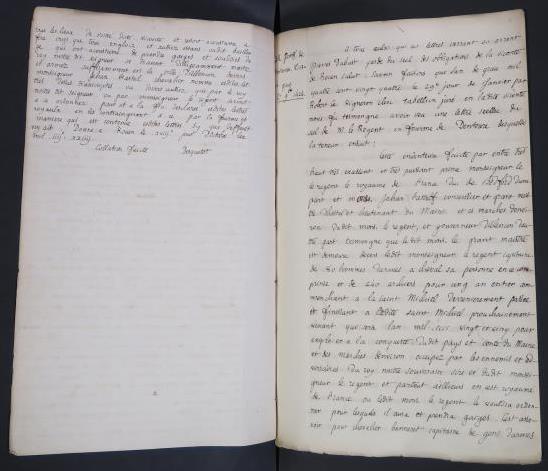

Three years later in 1424 he fought with his own retinue in the victorious Anglo-Norman army led by the Duke of Bedford at the battle of Verneuil. Although less well known, Verneuil was a more crucial strategic victory for England than Agincourt had been. Fastolf must have distinguished himself to his commander as the Duke of Bedford, who was regent of the French territories during Henry VI’s minority, granted him the barony of Sille-le Guillaume shortly after the battle.

Transcript of the Indenture contract between the Duke of Bedford and Sir John Fastolf (catalogue reference: PRO 31-8-135 (7))

In February 1429 Fastolf led a convoy of supplies to English armies besieging Orleans, with an Anglo-Parisian force, defeated a superior French army near Rouvray-Sainte-Croix. The victory was popularly known as the battle of ‘the Herrings’ because of the large quantities of fish among the supplies. It was to be the zenith of Fastolf’s military career.

Sadly this lofty success did not last. Scarcely four months after triumphing at Rouvray, an event occurred by which Fastolf would be judged by history, and that inspired William Shakespeare. On 18 June 1429 an English army was heavily beaten by a resurgent French force at Patay. Fastolf was part of that army but rather than engage, as his fellow commander the Lord John Talbot did, he withdrew with the body of men under his command.

Accused of cowardice, Fastolf was stripped of his position as a knight of the Order of the Garter. It would take Fastolf 13 years to clear his name.

Given that Fastolf was already a battle-hardened commander who had proven his mettle and guile at Verneuil and Rouvray, his actions appear to be more down to prudent assessment of the situation rather than abject reluctance to fight.

Though he would continue to loyally serve the English crown in northern France, commanding a number of garrisons in Normandy, his reputation was tainted. He would even be blamed several years later for the English military reverses in France by rebels in Jack Cade’s insurrection of 1451. They alleged that he was responsible for the diminishing of garrisons across Normandy that resulted in the loss of English lands in France.[ref]2. Stephen Cooper, ‘The Real Falstaff: Sir John Fastolf and the Hundred Years War’ (Barnsley, 2010), pp.118-123[/ref]

In 1439 Fastolf retired from soldiering in France and returned to England having served the English monarchy faithfully for nearly 40 years. Records in Chancery shed light on aspects of his later post-military life. For instance he was considerably litigious, appearing in a number of legal suits in the court of Chancery. Most litigation related to safeguarding of his property in East Anglia, as Fastolf had to contend with attempted interference by hostile local officials and landowners.

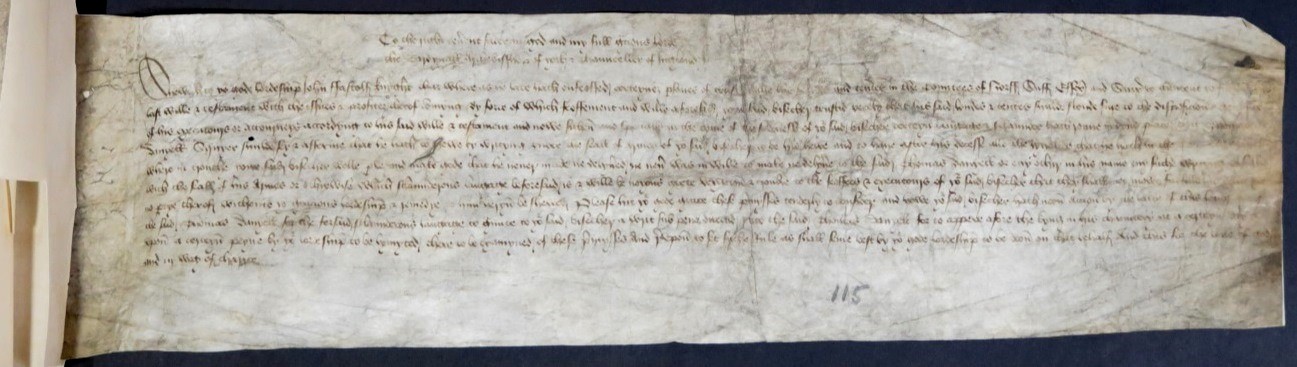

The record below indicates a suit pursued by Fastolf against Thomas Danyell esquire for his spurious claims of inheritance rights of the petitioner’s lands.

Proceedings of a suit in the Court of Chancery by Sir John Fastolf against Thomas Danyell esquire,1452-1454 (catalogue reference: C 1/19/115)

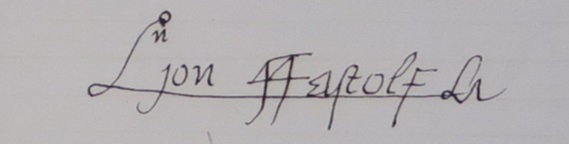

A copy of Sir John Fastolf’s signature (catalogue reference: PRO 31/8/135 (10))

Shakespeare may have the last word on Sir John Fastolf, but not in the way he intended. The famous phrase uttered by Falstaff in Henry IV part 1 – ‘The better part of valour is discretion’ – is widely known. Today, however, it is celebrated as an idiom of conventional wisdom rather than an expression of cowardice. Unintentionally it serves to pay tribute to the military prudence that made Sir John Fastolf the loyal and distinguished soldier he was.

I would dispute the ‘withdrawal’ at Patay (I am surprised you didn’t mentioned the document at TNA on the battle) in which Jeanne d’Arc was involved (and who changed the outcome of the 100 Years War) and that they the ‘English’ (with Burgundian support) army ran away. Of course England did not lose all of their lands as Calais held out until 1556.

Dear Mr Matthew,

Thank you for your recent comments.

With regard to the battle of Patay, the French forces under Joan of Arc surprised the English army led by Sir John Talbot, John Scales and Sir John Fastolf. French cavalry charges quickly overwhelmed hastily deployed archers in vanguard and rearward part of the army covered by Talbot and Scales taking them prisoner.

The chronicler Jean de Waurin who was with Fastolf before and during the battle of Patay states that Fastolf had although wanting to “return to the fray” was forced to retreat falling back to the town of Etampes. He may have had to fight his way out but the section of English forces under his command were not routed but were able to successfully withdraw albeit hastily. This is why I have used the term in the blog.

The rise of Joan of Arc did not in fact signal the beginning of the end of English rule in northern France and Aquitaine but it did put England on the defensive. However between 1431-1434, English military fortunes brightened under the competent military leadership of the Duke of Bedford, Sir John Talbot and also Sir John Fastolf. The real beginning of the end for English fortunes in France came firstly with the death of the Duke of Bedford and with the end to the Anglo-Burgundian alliance in 1435. Bedford was both an able military commander but also an astute ruler of English occupied lands in northern France and respected amongst the Norman French aristocracy. Without Burgundian support against the Dauphanists English military resources were even further stretched to counter this new threat to English interests.