Legacy was a major concern for William Shakespeare. Sonnet 55 argues that his verse will outlast contemporary worldly beauty:

‘Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme;

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone, besmear’d with sluttish time.’

Yet Shakespeare seems to have had the hope that, along with verse, his wealth might outlive him.

His last will and testament reflects a desire to consolidate his property and set up a substantial legacy for a male heir. However, only Shakespeare’s daughters survived to adulthood; his son, Hamnet, had died in 1596 at the age of 11. In the playwright’s last will and testament we see his attempt to transfer his lands to future grandsons, via his female heirs.

At the time of his death Shakespeare had two daughters: Susanna, married to the doctor John Hall; and Judith, who had very recently married Thomas Quiney. Susanna was left her father’s real estate, including four buildings in Stratford (New Place, the grand house in which Shakespeare had lived; the Maidenhead Inn; and properties in Henley Street – including his birthplace – as well as various lands) and an ex-monastic gatehouse in the Blackfriars, London. Judith, in contrast, was left money.

Shakespeare’s birthplace, Stratford-on-Avon, 1913 (catalogue reference: RAIL 268/63 (3b))

Susanna inherited almost all of Shakespeare’s property, exactly as his son would have done. It’s clear that he wanted to keep his lands together as one patrimony, not split it between two daughters. Was this because he had accumulated just enough to support one gentle family, not two? Being a gentleman was of great social importance.

Shakespeare’s aim seems to have been for this to be a temporary transfer of lands through Susanna to her unconceived eldest son, or to any of his potential younger brothers. Susanna had to pass the estate on as her father’s will required: effectively she had a life interest in it. Shakespeare did allow Susanna’s daughter (and only child) Elizabeth to inherit if she had no brothers, and to pass the estate on to her sons. If Elizabeth only had daughters, or had no children, the real estate would instead go to the sons of Shakespeare’s younger daughter Judith; if she had none, it would revert to a more removed male line.

Elizabeth was childless, but lived a long life. The property, acquired with the wealth Shakespeare’s success had produced, remained in her custody until her death in 1670. Then the remains of Shakespeare’s estate went to the grandson of his sister, Joan Hart.

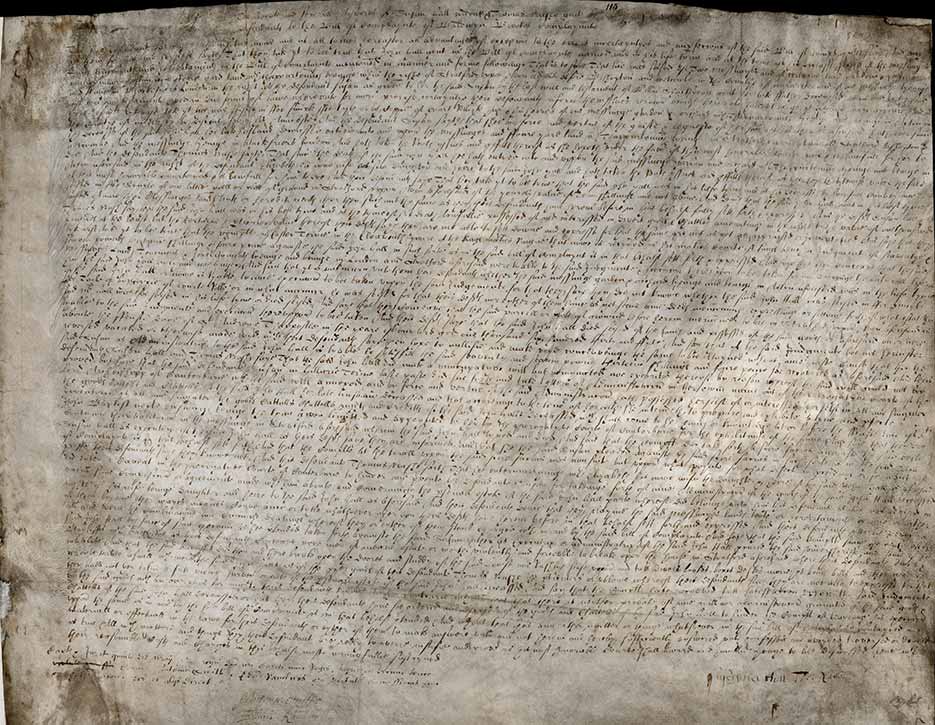

Much of what we know about Shakespeare’s family comes from his will, but his daughters and granddaughters can also be traced in other records held at The National Archives. From a suit in Chancery in 1637 we learn that Susanna may have inherited her father’s books. In these papers, found in C 7/49/115 and C 7/55/155, Susanna asserts that her son-in-law and his friend, a bailiff from Stratford-upon-Avon, broke into New Place and stole many works from her library.

Baldwin Brookes against Susanna Hall and Thomas and Elizabeth Nash (catalogue reference: C 7/49/115 (3))

On this document we can see Susanna’s signature, a fact which in itself raises interesting questions. While Susanna’s name is written at the bottom of this document, indicating her literacy, her sister Judith does not seem to have been able to write her name. In 1611 we find Judith’s mark witnessing a deed, now held at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

Without a male heir, and with even his female line dying out within two generations, Shakespeare’s vision of establishing a major gentle estate in Warwickshire came to an end. His legacy would be, as he himself predicted, the verse, which has survived for centuries.

It’s hard to know what to believe these days! First we hear that we have records relating to Shakespeare’s life, now we hear we don’t hav records relating to his daughters! “History” is weird!

Shakespeare’s grandfather Robert Arden left his property to his daughters (he had eight daughters) so it wasn’t unusual for women to inherit property.

Shakespeare didn’t own the intellectual property rights, as there was no such thing in the 16/17th centuries. The plays were written for the company so it was first the Chamberlain’s Men and then the King’s Men who owned the manuscripts to the plays not the Author, which is how Hemmings and Condell were able to produce the first Folio probably from the original MS.

Thanks to Hannah Leah Crumme and Amanda Bevan for such an interesting blog.